A brand-new band looks to beat the allegations.

SAMUEL HYLAND

When Bar Italia played at New York’s Mercury Lounge this past summer, there was a die-hard fan close enough to kiss Sam Fenton’s feet. It was surprising that he didn’t. He was wearing a freshly-purchased Quarrel T-shirt, one of several loose offerings at a ragtag merch table stationed across from a bar. This bar, as told to me by a friendly photographer, sold questionable beer that tasted like watered-down soda. And inside, down the dimly-lit hallway and past the throng of X-marked wrists, the band on-stage was battling similar allegations: questionable, watered-down, tasteless. By June of 2023, Bar Italia occupied a murky cultural middle-ground, one that flirted with a familiar post-punk ethos—lengthier songs, more distortion—but not without being shrouded, somewhat, in the hypnagogic fog of World Music, the cryptic Dean Blunt-run label they had just shirked for Matador Records. The group comprises vocalist Nina Cristante and guitarists Fenton and Jezmi Tarik Fehmi; often, their output feels just compelling enough to make you sway, not sweat. And yet, by the midway point—somewhat unthinkable, up to then—the fan’s newly-bought Quarrel T-shirt was drenched and dripping. It’s known that the band takes a militaristic, quasi-Ramones approach to performance; in the gaps where you might have anticipated stage banter, there was this particular teenager’s pubescent rasp, croaking things like “I love you!”, or “Nurse!!”, or “Skylinny!!!” The post-show trudge to Bleecker Street was long and lonely. The entire time, I was thinking more about this fan than the band he loved so dearly, so loudly.

“(I) Feel like an animal on a leash in pain.”

Bar Italia are enrapturing, but the reasons why aren’t necessarily new. As the 2010s slouched into the 2020s, they brought with them a tight-lipped vanguard of tiptoers, tightroping along the gap between alt-rock, an ossified genre, and hypnagogic pop, a fledgling one. The thing is, these are headquartered in entirely different worlds. Fringe rock feeds on fucked-up truths, the daily dread that compels a sufferer to condemn it through crappy microphones, funnel it through feedback loops, skewer it with Strats. Hypnagogic pop is, inherently, less anarchic than lethargic: its very name comes from the lucid space between sleep and consciousness, a foggy dreamscape on the precipice of a rude awakening. Its champions, the James Ferraros and Dean Blunts of the world, often sound like they’re half-awake, too—not so much singing as drawling, a mournful dirge for the Hells-Bells howling beyond their bedroom studios. And Bar Italia, fitting as both spheres seemed, crawled into collective consciousness a nomad: swimming between worlds, like something in utero, not yet strong enough to stake a bold claim to either.

If there was any “World” the band had citizenship in, it was World Music, the murky indie-house they nested in while the real world wondered who they were. Little is known of the label, but more often than not, it comes across as Dean Blunt’s H-pop plaything; its rotating cast of characters churns out sludgy sonnets, flecked with his affinity for echo-drenched vocals and slacker-rock swagger. When Bar Italia spawned from the imprint—World Music acts don’t get signed; they simply appear one day—they did so with a pair of earnest-seeming mini-LPs, Quarrel and bedhead. It was off-putting material that felt alt-rock in spirit, beholden to the decades-old dilemma of having the passion, but lacking the money. Or, in this case, lacking the drummer. Most songs utilized a sullen-sounding drum machine, wearisome and distant as the cold voices droning over it. “Feel like an animal on a leash in pain,” Fenton sings on “Skylinny,” one of the more popular tracks on Quarrel. They sounded like it, too.

I think about the sweat-drenched fan at the Mercury Lounge show often: he was passionate and shameless, so much so that it seemed to cancel out the band’s more passionless, shameful moments. Which were, to be clear, very few. Bar Italia tour with a full lineup—complete with a bassist and (yes!) a drummer—so seeing them live, especially that night, was a spectacle in realizing what they would do if they could. They played loudly and mechanically; cathartic as their set often felt, it was also somewhat soulless, a sock-deep soup of squall and stompbox. And maybe, just maybe, that’s exactly what I had come for—not only to the Mercury Lounge show, but to Bar Italia as a concept, even more so than a band. Like Blunt, despot of the reticent U.K. fray they’d flown in from, they’re something of a beacon to artsy loners, the sorts who would much rather speak from a studio, or a Squarespace, than a soapbox. Quarrel and bedhead each leave a bedroomy, hypnagogic aftertaste; their live renditions boast oppressive alt-rock tyranny, alien and occasionally arena-sized. The strange thing about Bar Italia is, very much, the strange thing about the 21st Century: when you reckon the digital footprint with the person who exists in real life, they’re typically two very different entities. And whether we’d like to admit it or not, the shadowy cocoon of the digisphere is often far cozier to call home.

“When your white ex tells you she is superior to you… Yes you get petty and delete the devil. Last on this, die slow.”

When Bar Italia arrived at the Mercury Lounge, they were midway through a months-long tour for Tracey Denim, their freshly-released Matador Records debut. Matador has a well-documented knack for brainy experimentalists—Sonic Youth, Dälek, Pole—and in some sense, the Bar Italia signing seemed like something to be grown into, an open invite into a larger, more eclectic cultural canon. But unlike the wraiths who whispered through Quarrel and bedhead, this iteration of the band seemed particularly apt for broader borders, eager for more sand to play in. Tracey Denim wasn’t the sort of thing you heard on World Music: where their alma mater specialized in the woozy and insular, their new music felt unashamedly aspirational, the stuff pouty prep-schoolers make in “study sessions” that occur in their fathers’ fucked-up garage studios. They weren’t appendages to Dean Blunt’s extended universe, anymore—they were a fledgling entity of their own, equipment bags slung over their shoulders like Gibson-branded hobo sticks.

The interesting thing, and what makes their predicament snaky, is this: as 5:30 stumbled into 6, and the loose stragglers loitering doorside festered into a long line of ticket-holders, their small-talk wasn’t about Tracey Denim, or Matador, or any of these things—it was about World Music, and the new, somewhat-identical band that had just spawned onto its roster. Not long before the New York show, Blunt had begun steadily soft-launching The Crying Nudes, a group strikingly similar to the one sound-checking inside: sad-sounding female lead, ragtag guitar riffage, bucketloads of reverb to wash the skill issues away. Blunt’s discography is peppered with shadowy white-woman collaborators; every now and then, though theories of romance are largely unconfirmed, a “breakup” of sorts occurs, even if said split is solely on musical terms. In a dated interview with the Russian magazine Афиша (“Poster”), he told a journalist that “Imperial Gold,” from 2013’s The Redeemer, wasn’t “100 percent my track, it’s a girl named Joanne Robertson singing, with whom, of course, I slept.” The Redeemer itself followed the dissolution of Hype Williams, the experimental duo he comprised with Russian provocateur Lolina, founder of Relaxin’ Records. Many leapt to interpret it as a breakup project, and in the absence of concrete facts, there was (and remains) a vengeful document to be contended with: 44 minutes of sad-boy sludge-pop, drowning in doldrums that get deeper when interpreted as heartbreak-borne. A few months after the New York show, Blunt would go on to delete a hefty portion of Cristante’s music from Spotify; while fans theorized, she posted a screenshot of the grayed-out tracks to her Instagram story, tersely adding “when u tell your ex your [sic] seeing someone else.” Shortly before he deactivated his account, Blunt retorted: “When your white ex tells you she is superior to you… Yes you get petty and delete the devil,” he wrote. “Last on this, die slow.”

“Your pretentious ways make me die a little.”

If there’s anything to be gleaned from this history, of breakups and cutbacks, it’s that Blunt may be as controlling as he is cryptic. He’s been quiet (at least on streaming) since last summer, but his sphere of influence looms large, which makes Bar Italia’s hurdle distinct: much like the despot himself, Blunt-obsessives who arrived at the band through him also see the band through him, analyze it through him, interpret it through him. And as flashy as a new record deal may be, a new arbiter doesn’t equal a new context, let alone an easy escape from the old one. With Tracey Denim and the tour that ensued it, they were fighting allegations in real time, allegations of being aloof, low-effort, watered-down—like both the lowbrow beer at the bar, and the highbrow hypnagogia at their ex-label. When a band like their own goes long enough without doing press, there’s an automatic haze that descends over their output, one that renders everything they do hyper-questionable: What are they referencing? What are they critiquing? Who are they making fun of? Difficult as it may be for overthinkers to admit, sometimes—maybe most times—it isn’t that deep: the cryptic bookish mysterious chic band is just trying to make music. Music that sounds a lot better when there isn’t someone in your ear asking if you listen to Dean Blunt.

💂💂💂

“I’d rather be known as boring than mysterious right now.”

Bar Italia’s sophomore Matador LP is named for The Twits, a fucked-up novel by Roald Dahl—an equally fucked-up man—in which the titular twits make pies of bird feet, slurp days-old morsels from their own beards, and severely mistreat their pet monkeys. The members of Bar Italia do none of these things. But where Dahl saw a whimsical narrative flecked with sinister, blood-red undertones, it’s possible that the band saw something vaguely instructive, loosely applicable to the grungy groundwork that lay ahead. They were a bona-fide turning-point act: split between a languid legacy and a lucid one, hellbent on spiking old whimsy with worked-up rage. Which is, of course, not seemly of a group more shy than scathing—you don’t go Bar Italia’s music, nor their shows, to let it all out after a wild week. Their output is more fitting for Mondays, their so-so spirit of slightly-effective coffee, slow-walking streets, sleepy faces lit by not-so-sleepy spreadsheets. And on one recent Monday, as pairs of shoes pooled, like early-week dew, in the cramped foyer of Nashville’s Third Man Records, Bar Italia were somewhere inside, sound-checking stuff that didn’t seem as snoozy as the ticket-holders small-talking in the rain.

“You can cut the music now, thanks.”

The previous September, a tour announcement for The Twits was accompanied by “my little tony,” an aggressive, arena-sized lead single—so aggressive, in fact, that many interpreted it as a thinly-veiled Dean Blunt diss. “Your pretentious ways make me die a little,” Cristante sang in its opening moments, straddling a squall of fuzz-pedal fury. By the track’s end, she was goading someone unnamed, deadpan vocals ticked up to sing-songy, teasing territory: “Keep playing with my receiving hand, ‘cause you know you’ve lost the game.” “My little tony” is the opening track on The Twits, and it’s fitting that “You” emerges as its central figure—a loose stand-in, one that might mean “You,” a specific person that exists somewhere, but also You, the reader-listener, an imagined interlocutor the band is newly interested in addressing directly, unapologetically, unwhisperingly. “Bibs,” the final track on the project, rides an unnerving melody into an eerie deconstruction, buoyed by finger-pointing lectures to this anonymous wraith—someone who tries to speak, but can’t, because every time they open their mouth, their tongue “rolls back on their teeth.” It might sound familiar. Bar Italia spent their first few years unsmiling and unspeaking, shrouded in what Philip Sherburne called the “default intrigue that attaches to certain bands who decline to overshare.” In the run-up to The Twits’ release, they offered the first-ever interviews of their career; in each one, they seemed vindictive, even offended, of the “cryptic” descriptors that clouded their earliest efforts. “It was fine for a while, but it’s got to the point where everything that’s written about us is caveated with the word ‘mysterious’,” Fehmi told the Guardian. “I’d rather be known as boring than mysterious right now.”

It’s a gruff-sounding sentiment, but one that feels apt: Bar Italia want to be known, and they deserve to be known, even if they’re known for being unmemorable. Which is desperate. But a good, necessary desperate—regardless of whether they’re eager to wear it on their faces. Aside from the sweat-drenched fan, the most interesting thing about the Mercury Lounge show was the moment they walked on-stage, sulky and slightly annoyed. The pre-show music was still playing, and they were trying to get the PA person’s attention: lightly tapping mics, glaring through squinted eyes, letting guitar feedback squeal, untamed. The in-house music continued its tyrannical thump; the people halted their applause, slowly and awkwardly, surrendering their mutiny against more-powerful venue speakers. And only when he realized that he had to, Fehmi took hold of his microphone, pulled it close, and said his first and last words of the evening: “You can cut the music now, thanks.”

Bar Italia enlisted two openers for their Nashville show, and for each of their sets, the lights were dim, a depressive, dying blue. Somewhere around 8, a dazed-looking woman with a baseball cap trudged to a lonely corner of the stage; behind her, a projector casted ghoulish imagery against the back wall—time-lapses of ticking clocks, anguished faces, day turning into night. When she finished her selections, she stooped down to sip from a can. And in her absence, which loomed large even when she was singing, the images were deathly and somewhat unnerving: a bright-white reminder that not only was time ticking, but it was running out, too. Which was funny. Funny, because her set was followed by the polar-opposite Messthetics: a funky quartet of groovy, bookish-looking men who arrived in cubicle-clothes, played crucifiable offenses in most conservatories, ignored their phone calls, cracked jokes, liquidated the memento-mori she instated, then left. When an old reveler near the front reached for their sheet music, James Brandon Lewis, the saxophonist on their newest record, swiped it away with a smiling “I need that.” Thank you, Messthetics. I needed that, too.

“Thank you for having us… Nashville.”

And by 10:15 PM or so, the people needed to sit down. They’d been jittery, shifting their weight through both opening sets; post-Messthetics, a look across the sea of heads yielded a swaying mass, each body seemingly troubled by tired feet, or traumatized by sax-guitar-sex-jazz PTSD. At any show, specifically any show with two-plus openers, a scene like this is typical: beneath every pair of swaying shoulders is a pair of swollen soles, dancing between acts to convince themselves that they aren’t suffering. But they are suffering, and that’s what makes it bearable—they’ve been here before. Bar Italia had, too. Just like the Mercury Lounge show, they mounted the platform and plugged in their guitars, tapping mics and letting feedback fester. The in-house music was still playing.

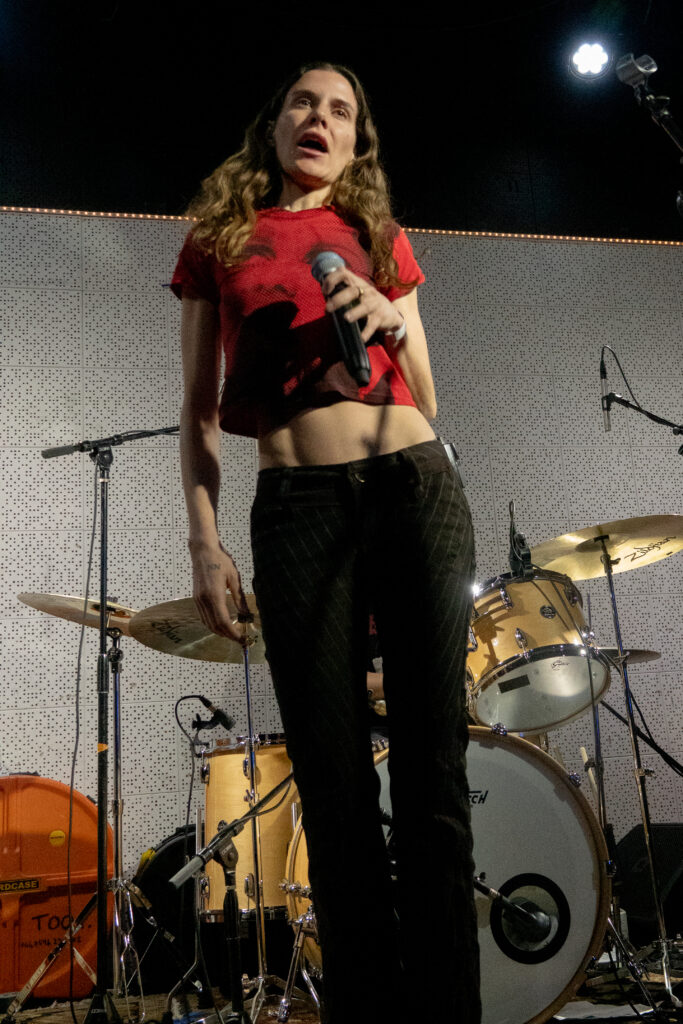

But this time, Fehmi didn’t have to say anything to make it stop. And this time, too, the lights were bright, white, and blinding: when they walked on-stage, it was as if they’d walked into a police lineup, stoic faces on display for the curious souls swaying, shouting, behind the glass. They seemed to have coordinated their outfits; if this is true, tonight’s theme sat somewhere between blood-red, racy, and business-casual. Cristante wore a paper-thin crop-top emblazoned with an unsettling face; Fehmi and Fenton wore tucked-in button-downs and dress shoes, scowling as if to make their mouths accessories. They could have been really bummed, really nervous, or really into it. The rhythm section—the group’s touring members—often exchanged light-hearted smiles; sometimes, the drummer would smile at Fehmi, and he wouldn’t smile back. In the first of two awkward silences, the group exchanged fleeting half-glares, to each other, then to the hand-scrawled setlists at their feet. The second time, Cristante hesitantly leaned into the mic, muttering, as if taken aback by the sudden burden of having to speak. “Thank you for having us,” she conceded, with a sheepish half-smile. “…Nashville.”

“Your head is full of worries, and nothing ever happens.”

Watching Bar Italia live is largely a game of figuring out who you should be looking at. It may have been an issue with this venue specifically—sometimes, when Fehmi seemed to be singing his heart out, all you heard was drums and guitar—but I remember swivel-necking just as much at the Mercury Lounge, recording one member with my phone, then realizing (too late) that the voice I heard was coming from the other side of the stage. Triple-pronged vocals are a hallmark of their work; oftentimes, in their recordings, they sound like haunted triplets, hypnotizing their way into free candy. And as I write this, I’m realizing that over the past four or so years, I’ve only ever really spoken, or written, about them in analogies. Haunted triplets, trenchcoat-clad killers, pouty prep-schoolers, TVU-types. Boring as it is to admit, being a fan of something also means mythologizing it, brushing over boring bits to make room for the more sellable, packageable, obsessable. It’s how the shy become the “mysterious,” the grim become the “gothic,” the unsigned become, automatically, the “up-and-coming.” In the gaps where we don’t understand, we race to forge legends, even if only for ourselves—not because the musicians aren’t cool as is, but because a world where we can’t relate is a world where we can’t exist. And the truth is, Bar Italia are simply a band of young adults: young adults who, like other young adults, are somewhat shy, have a shared passion that outshines said shyness, use said passion to achieve catharsis, and are kind enough to share said catharsis with us. Their world is theirs. Ours is ours. Sometimes they intersect. Sometimes they don’t.

That Monday, when the hour-long collision between Bar Italia’s world and ours ended, it did so with another “world,” and one that wasn’t called World Music. The final song of their set was “world’s greatest emoter,” a Twits single that feels just as fitting on a Matador disc as an EA Sports one. “Your head is full of worries,” Cristante sings, in its chorus. “And nothing ever happens.” Like many things about Bar Italia, it’s very boring. Like many things about Bar Italia, it’s very true.