CITY SMELLS

Post-midnights, empty empires, and art that starts cults.

SAMUEL HYLAND

On a blood-stained beach hugging the edge of Ostia, Rome’s outermost municipality, a prominent filmographer has been brutally slaughtered with fists, motor vehicles, and gasoline. He might also have killed himself. All we can glean is from what we’re told: it’s eternity o’clock in purgatory, and he’s pacing back and forth before a giant television, watching his own snuff footage on infinite loop. Since about five minutes ago, when he was informed that we’d be observing him today, he’s been hard at work on a tell-all monologue. It opens with a pair of questions: “Did I ask to die? Was my murder a suicide by proxy?”

Pitiful as he may sound, you don’t have to worry, and you don’t have to answer, either. He’s a classic Kathy Acker character: he’ll try to talk to you, but it’s just a thing he does; you know, good old (ambiguous troubled half-entity #27), always rambling about death and destruction and the like. Go ahead—say something back. Don’t be shy! Exactly. He can’t hear you; you can’t understand him; the more you try to understand him, the more queasy you feel, et cetera. Accept it or not, you, too, are barrelling towards a fate like his, and every confusing word he speaks is a memento mori. It’s like talking with a demented, dying relative.

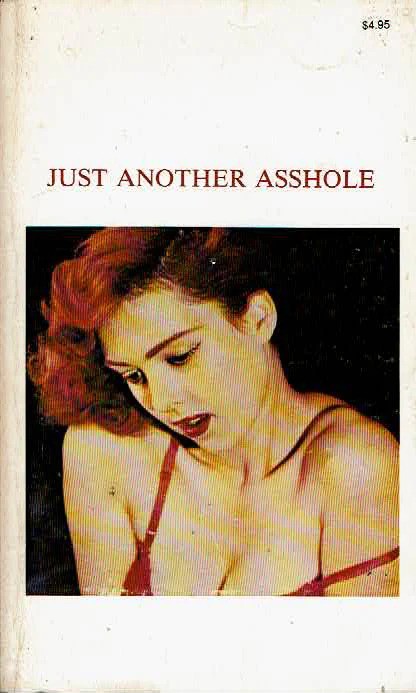

Deadpan and wraithlike, this deceased man—a creative reimagining of the director Pier Paolo Pasolini—centers “MY DEATH,” one of several off-kilter short stories comprising the sixth installment of Just Another Asshole. Little concrete information exists about the serial, nor its exact premise, aside from the fact that it was curated by Barbara Ess, a Warhol-type scenester who found mutual friends in New York’s experimental art world-dwellers. Earlier editions featured strange photographs and works of short-form criticism; for #6, it seems as if she gathered a few dozen mutuals — among them: gallery-world enfant-terrible Richard Prince; Sonic Youth guitarist Lee Ranaldo; Swans frontman Michael Gira; conceptual commenter Jenny Holzer — and had them submit blurbs of Acker-esque nonlinear fiction, more beholden to the “horror” in “horror story.” Taken in one breath, the tales’ most jarring and permanent facet is the spirit they share: fatalistic, ghastly, nauseous, not entirely present. “There’s no reason anything should be a certain way in our lives,” Acker’s narrator suggests towards “MY DEATH”’s end. It is on this rock, of placid noncommittal, that both he and you are left to perish.

“Hell, like many things post-internet, is more a state of mind than a physical place where you can be killed with fists, motor vehicles, and gasoline.”

Ess’s particular New York, of Fear City pamphlets and wee-hour slashings, bred an interesting avant-garde intent on scoring its inferno, whether via noisy sonic arrangements or provocative visual statements. Several decades later, it’s the only vacuum Just Another Asshole entirely makes sense in: hellish literature arises from hellscapes; we revisit said hellscapes to remind ourselves that they existed, or, age considered, that we survived them. But in our much-glossier reality, when most of those streets have been gentrified — (tasteful witticism about Starbucks locations) — it’s difficult to be moved by art that channels their pasts, let alone seeks to make a case for their permanence. And though it’s taken me forever to realize, this is the trouble with an album I fell in love with last October, and spent the remainder of the year obsessively mythologizing. In 2013, the art-pop provocateur James Ferraro sought to make a project that soundtracked dark Manhattan post-midnights, where the loudest noises weren’t disembodied wails nor clankings, but internal, existential dread. In a sense, this is an effective mapping of old-world folklore onto digital-era realities: where the mass destruction of pre-Giuliani New York was fascistic and visceral, perhaps our hellscape is mostly in our heads, nuclei of yuppie stressors — rent, roommates, landlords, day jobs, fuckface mayors. Yet there’s little denying that these are first-world concerns, alien to the New York whose “underground,” all those years ago, was primarily an “underground” because it lived and worked in its own filth. You can be underground from an Upper-East high rise; Hell, like many things post-internet, is more a state of mind than a physical place where you can be killed with fists, motor vehicles, and gasoline.

Ferraro’s music tasks itself, often, with muzak-ifying similar cultural molting phases — not far off from the “score the city” No-Wavers Ess orbited, save for the fact that his work is far less noisy, and far more seductive. He’s said, in interviews, that he seeks to make a “social lube for capitalistic transactions.” (The cover of his most popular record is a man wearing an Amazon box like a paper bag; NYC, Hell 3:00 AM’s digital artwork is an array of barcodes.) Pretentious as his premises may sound, they’re a gold-standard of hypnagogic pop, one of several distinctly-online genres intent on “soundtracking” societal oddities via dreamlike, escapist arrangements. But if the H-pop of Ariel Pink and George Clanton is utopian and ethereal, Ferraro’s take on NYC Hell is markedly sinister, less concerned with dreams than the agony of having them slip through your fingers. Though he wasn’t alone in the tortured-artist schtick, where depressive music is made to sound like it’s coming from an angle—see: Dean Blunt, The Redeemer—he was the premiere figure doing it in a specifically New-York context, fresh in a lineage of forebears who saw Hell in their city, and wanted to make art that sounded like it.

NYC, Hell 3:00 AM’s recording sessions were held exclusively after midnight, one among several prongs of an attempt to “embrace that moment where you’re stuck with everybody.” In a statement provided to Resident Advisor, Ferraro described the project as “a surreal psychological sculpture of American decay and confusion,” citing inspiration from “rats, metal landscape, toxic water, junkie friends, HIV billboards, evil news, luxury and unbound wealth, exclusivity, facelifts, romance, insane police presence [and] lonely people… all against the sinister vastness of Manhattan’s alienating skyline.” Much like Just Another Asshole #6, the record is materially successful—not necessarily because it makes direct statements, but more so because it draws on a distinctive spirit, be it of unease, nausea, death, or deconstruction. It’s sludgy, decadent R&B music that processes everything interesting about the genre—the hummable hooks, the fuck-me-now freaky-isms, the arena-sized audacity—through an avant-garde-inator, one that renders nothing hummable, fuckable, nor approachable. “I know you want to love me,” he lazy-croons, as if in the shower, on a track called “City Smells.” (The track’s brief intro section features words from a female, text-to-speech cyborg: “Xerox JPEGs pixelated sexy 100% sexy.”) “…But it’s life in the empty city.” For all its rhetorical remove, it sounds like something blatantly derelict, and blatantly 3:00 AM on Canal Street. Like anyone else muttering after midnight on LES, perhaps we don’t understand him because he was never talking to us in the first place.

“While the art writhes on its deathbed, the city it serenades is passing by without a greeting, smile, nor glance, busy killing someone else.”

Written by Constance Ash, the second story featured in Just Another Asshole #6 centers around an elusive goddess and a submissive acolyte, desperate to witness, let alone worship, his savior. “I shivered with the desire to rush to her, to fall at her feet, to throw myself before her, to seize her dainty foot and kiss it, to be walked on by her little shoes,” the servant bemoans, at one point. When she passes him by without a greeting, smile, nor glance, the parishioner is rebuffed at best, and devastated at worst: “My bondage was completed. I was paralyzed. My being dissolved in a sea of tears. It was bitter delight now, to see my lord and think of her, to dream of serving my lady.” It’s difficult to trace where exactly James Ferraro is coming from with anything, but listen closely enough to NYC, Hell 3:00 AM, and it begins to feel slightly like this parishioner’s internal dialogue—clingy to a void incapable of reciprocating; desperate to project insecurities onto a blank canvas with larger-than-life ethos. Which, in the larger scheme of things, isn’t necessarily Ferraro’s fault. The draw of NYC Hell, a decade later, is increasingly square with the appeal of Just Another Asshole: more artifactual than concrete, and infatuated with giving consumers found-footage to piece together, no matter to how little avail. More than ever, in a reality constructed by safety nets, it’s something of a fetish to see what goes on after midnight, to be dominated by a city that used to pride itself on ruthless dominion. This impulse saturates the record’s tortured-artist premise—it’s in the 9/11 news broadcast samples, the subway rat ASMR, the “Upper East Side Pussy.” But as authentic as these things are, when strung together loosely for a tragic “concept” project, they can only ever function as vapid ephemera, an empty bludgeon wielded to beat fellow-proselytes over the head. It works solely when Ferraro is around to explain it; when he isn’t, it’s desperate, depressive, and dying. While the art writhes on its deathbed, the city it serenades is passing by without a greeting, smile, nor glance, busy killing someone else.

One of the most effective things about Just Another Asshole, in comparison to NYC Hell, is that it offers zero self-explanation, neither before nor after the fact: a more authentic iteration of “avant-garde” art, and one that remains largely true to existence in a vacuum. Because its characters are hopelessly trapped—poring over their own snuff footage, worshiping entities that refuse to acknowledge them, dying gruesome deaths—we are doomed to be their chaperones, somewhat reenacting the parasocial relationships they’re sentenced to endure. Non-contextual art works, inherently, because it forces a consumer to adopt its suffering, no antidote readily available to oppressive, murderous confusion. In a music-media landscape where all things must be accounted for, because muddiness equals unmarketability equals failure, it’s difficult to create work that accomplishes such feats without sacrificing money, credibility, or listening ears. I get the sense that James Ferraro wants to be understood, which is why he placed effort into contextualizing NYC Hell, crafting for it a pre-set, press-release-outlined landscape to live, churn, and comment from. But in a way, this is exactly what it gets wrong about the empty city it scores: the answers are there, and as hell bleeds into our ears, there’s someone holding our hand from Earth, making sure it makes sense.

🌎🌎🌎

“There’s awareness of a place to go, but the catharsis, if any, lies in the fact that you will never get there.”

When NYC, Hell 3:00 AM was released in 2013, New York City’s mayoral office was held by Michael Bloomberg, an ambitious technocrat who sought to revitalize his domain via riches and rezonings. Ten years later, it’s interesting to see the Big Apple’s figureheads—especially in the context of Ferraro’s project—as caricatures in a dystopian epic, the sorts of well-spoken political villains best witnessed on blown-up, assembly-facing projector screens. As I write this, Eric Adams is latest in a slew of mayoral main characters, perhaps equally as notorious for his disposition as his questionable politics. “New York!” he said in a recent interview, asked to describe the city’s 2023 in one word. “This is a place where, every day you wake up, you can experience everything from a plane crashing into our trade center, to a person who’s celebrating a new business that’s open. This is a very, very complicated city, and that’s why it’s the greatest city on the globe.” What made the gesture so see-through then, besides its concerning 9-11 selling point, is that he was very obviously reaching for two things: (1) nuance (or the guise of it), and (2) trust. As much as he may know, firsthand, the complexities of his adopted terrain—or not: it’s common knowledge that his true home is New Jersey—his knee-jerk attempt at description relied on vapid callbacks, old talking points from old regimes. The 9/11 shtick is a distinctly Giuliani trick; the “business openings” have bailed press-conferences balkers out for decades. And thus, when panicky 9/11 broadcasts are invoked on “Stuck 1,” they feel less like a guide to lesser-known New York hells, and more like something Eric Adams would throw in a campaign ad: vapid, low-hanging shock bait.

“a public death of the world’s soul spread like a virus by billions of smart phones and snapchat accounts. a world of images disseminated and murdered too fast to discern what emotional prehensility could save us from ourselves.”

James Ferraro has long been infatuated with the September 11 attacks, and NYC, Hell 3:00 AM isn’t the only time he’s played with their lofty symbolism. In 2017, he staged a conceptual reimagining of the Twin Towers’ destruction via Roblox, where aircraft were replaced by sentient fidget spinners, and a crashing-through-the-buildings POV replayed itself every few seconds. (In the film’s final scene, the POV is shown once again, except this time, it’s headed into One World Trade.) “and thus the towers fell,” a closing statement began, rolling up-screen the way credits would. “a public death of the world’s soul spread like a virus by billions of smart phones and snapchat accounts. a world of images disseminated and murdered too fast to discern what emotional prehensility could save us from ourselves.”

Much like the attacks themselves, the legacy of Ferraro’s experi-movie is plagued, even now, by overstimulation—too many replays, too many angles, too many noises, too many casualties. And the thing is, at least by hypnagogic pop standards, this is wildly successful. Denizens of the genre often make comments via sensory triggers, less a musical impulse than a cinematic one. There’s a “hypnagogic” way to listen to everything; that is, if an album fails as a piece of music, there’s a slight chance that it might succeed as conceptual, collagist aggro-art. What NYC, Hell 3:00 AM does well, maybe even to perfection, is straddle this difficult tightrope: when the music flounders, the loose ephemera is barely compelling enough; when the ephemera is vapid, the music accomplishes its desired effect—Manhattan melancholia—in its place. It’s why, even though I see through it a bit more every listen, I still can’t stop coming back: be it preachy, vapid, narcissistic, or destitute, it’s also very brutal—and painful as it is to admit, very beautiful.

Listening back to the project, I’m reminded of À rebours, a watershed text of Europe’s languid 19th-Century decadent movement. Written by Joris-Karl Huysmans, the novel centered around a vain aesthete desperate to (1) shield himself from the outside world, and (2) live his solitary life in pursuit of indulgent vanities. (During one disturbing stretch, he plants layers of gemstones beneath the shell of a tortoise. The tortoise dies under the weight.) This was radical then, and remains somewhat compelling now, because it subverted linearity and logic for plotless, inconclusive meandering. There isn’t an arc to the story, nor a resolution to its central character’s ills: he’s rich, he’s pissed, and he hates the world for being too boring, too ugly. “He lived within himself, nourished by his own substance, like some torpid creature which hibernates in caves,” Huysmans wrote of his selfish recluse, at one point. “Solitude had reacted upon his brain like a narcotic. After having strained and enervated it, his mind had fallen victim to a sluggishness which annihilated his plans, broke his will power and invoked a cortège of vague reveries to which he passively submitted.” It’s arguable that this sluggishness, especially when enabled by the internet, is what Ferraro largely operates against—if the afterword of 9/11 Simulation In Roblox Environment signals anything, it’s discontentment with lives lived exclusively behind screens. But in a sense, and in his own words, it’s also something he’s painfully familiar with. NYC, Hell 3:00 AM was conceptualized with “mental stuck” in mind, a rut he’s credited to “(the) immobility and claustrophobia of living here or being on the subway.” Listen repeatedly, and the record feels a lot like being trapped underground, surrounded by tense strangers on a delayed train: there’s awareness of a place to go, but the catharsis, if any, lies in the fact that you will never get there.

Mediums aside, and regardless of what they accomplish—or fail to accomplish—in pursuit of “avant-garde” art, Just Another Asshole and NYC Hell are linked by decadent, maddening stagnation. Much of the stories in Ess’s collection, like À rebours, are plotless and off-kilter; Ferraro’s LP gestures towards familiar R&B signifiers, but leaves them flat, confused, and decaying. I borrowed a friend’s copy of Just Another Asshole #6 last December, around the same time that I began revisiting NYC Hell in-depth. It was hard not to feel mentally, if not literally, trapped: sifting through the works of Ess’s interlocutors, and their twisted, experimental minds, was an exercise in endless re-reading, wondering whether apparent mistakes—plot-holes, grammatical errors, unfinished words, unfinished sentences—were intentional or misprinted. More often than not, it made me think of times I’d showed up to art openings alone, not knowing what to expect. Sometime last summer, at a well-hidden gallery space on Canal Street, I could only spend 20-ish minutes ogling before I grew desperate to slip out, away from the growing crowd, away from the rising, maddening din of loud-talking friend groups. “It literally is—just networking,” an art-world person told me outside, along the way to the subway. “That’s all it is.”

“Time is moving on anyway / to lose yourself away.”

While Ferraro’s music is escapist in nature, it also feels just as stuffy, sweaty, and claustrophobic. If I were to guess, I’d say he’s repurposing those sensations to subvert them, maybe create something that testifies to surviving their evil. But at the same time, he could also be lavishing in the sinister glory of it all—more concerned, like Huysmans, with the aesthetic of wickedness, even if said aesthetic requires one to become a monster. From last October to now, the track I’ve revisited most on the project is “Eternal Condition,” a languid slow-burn that fuses trappy drum-chops with ghastly, melancholic sleep-singing. “Time is looping on anyway / Time is moving on anyway,” Ferraro muses at one point, seeming half-convinced, half-alive. “Time to lose yourself away.” The more I replayed it, over the two or so weeks my friend let me borrow Just Another Asshole, the more he began to sound vaguely familiar. Kathy Acker’s Pasolini, lifeless in his confusion, is victim to a similar set of circumstances—lack of knowing, lack of animation, lack of interlocutors, lack of energy. Decades and miles removed from one another, the pair’s manifestos are eerily plagued by similar ills: their disorientation is haunting, uneasy, and, perhaps most vitally, fatal. We talk to them, but much like the ugly cities they—and perhaps we—suffer under, they’ll never hear us.