Self-hypnosis for the moments where ethos and existence part.

SAMUEL HYLAND

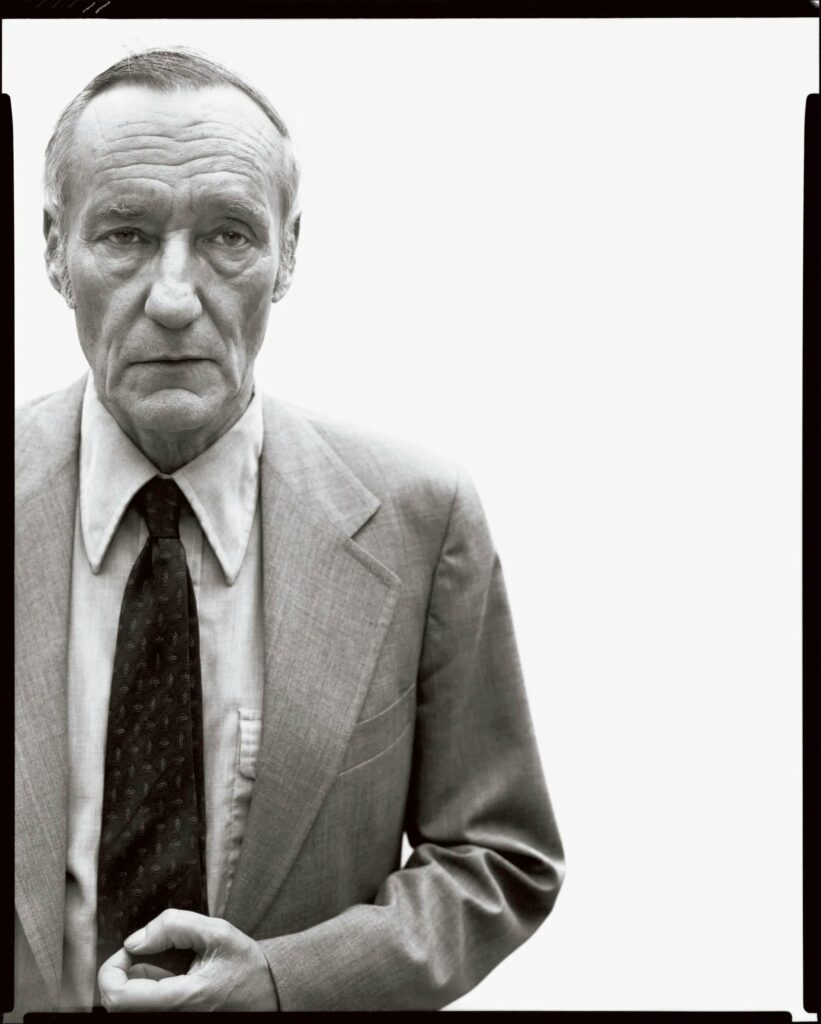

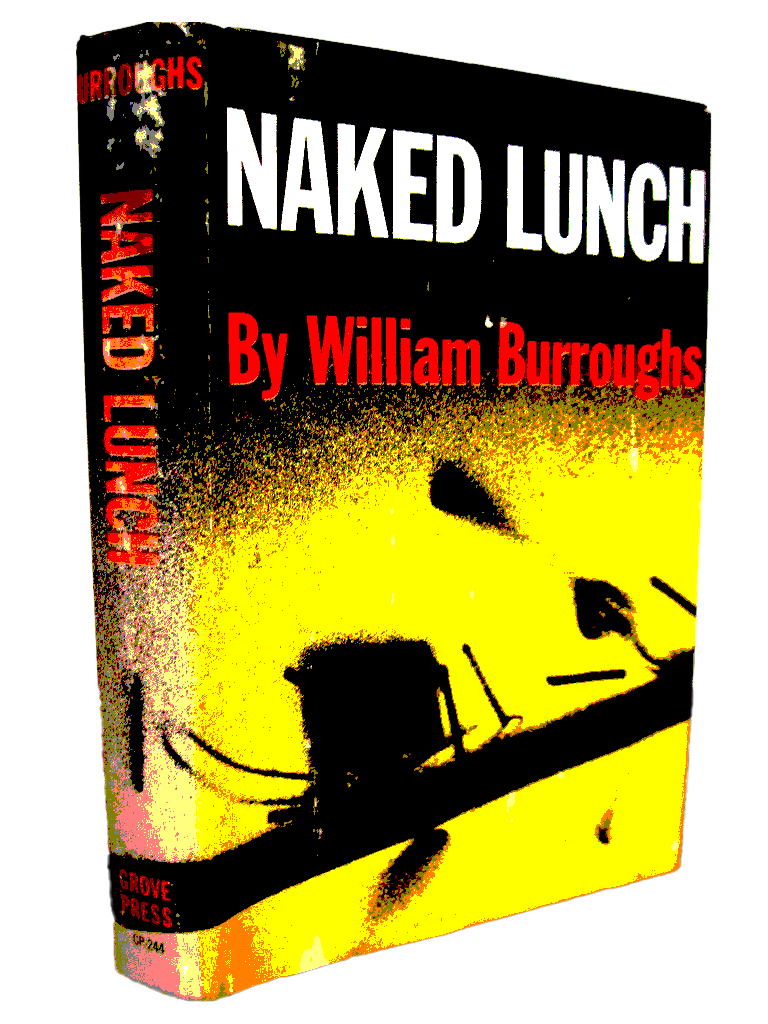

Within ten pages of William S. Burroughs’ 1959 psychological novel-slash-treatise-slash-experiment Naked Lunch, we are introduced to an unnamed dope dealer whose elusive nature alone—in tandem with his trademark tendency to hum loose melodies on street-corners—is bewitching enough to lure diverse hordes of prospective clients. “He is so grey and spectral and anonymous,” multi-aliased junkie narrator William Lee notes, “(that) they think it is their own mind humming the tune.” Naked Lunch describes itself, on the back flap of its first-edition Grove Press hardcover, as both a “tour of Hell (exposing) how sublime human nature is,” and comparable, per an unspecified “some,” to the prophetic visions of Dante. Although the “tour of Hell” portion wastes little time proving true for Burroughs’ drug-ridden underworld—also within ten pages: a desperate, involuntarily-hospitalized woman butchering her leg wide open with only a safety pin, so as to bless one of her few remaining non-withered veins with heroin—any advertised prophetic capacity is relatively subjective, and only really vouched for by the text’s overarching obscurity. Naked Lunch is, perhaps intentionally so, bathed in indecipherable vernacular, and an equally-indecipherable plot line that skips from the bowels of New York City’s unforgiving drug infrastructure, to made-up dystopias like the “Freeland Republic” (where “Citizens with incipient Bang-utot clutch their penises and call on the tourists for help”), to squint-conjuring, pages-long monologues about the human capacity for sustaining prolonged torture. But somehow, after you’ve feigned understanding for long enough, it appears to work: much like the hordes of diverse junkies slouching towards their ghastly plug, you, too, are convinced that it is your own mind humming the tune.

“The selling point of it all may really have just been the experience of falling.”

When I frantically ordered Naked Lunch on the shady website of a second-hand bookseller, it was a little after six in the morning on a November Wednesday, and I had just read in a forum somewhere that Dean Blunt and Inga Copeland thought it was cool. Blunt and Copeland, the latter of which now performs as Lolina, comprise a mysterious London duo called Hype Williams, which is widely rumored to no longer exist. Blunt, the symbolic epicenter of the duo’s larger obscure UK scene, banks just as heavily on a certain militaristic mystery, seldom ever speaking or appearing publicly beyond the context of his get-it-or-you-don’t (you definitely don’t) sonic footprint. He primarily performs under his own name and “Babyfather,” an enigmatic side-project whose sole available press photo features a swagged-out trio, but really might just be Blunt himself on up-pitched vocals.

My first encounter with Blunt’s lore came to the tune of “LUSH,” the violin-studded opener to his complicated 2014 LP BLACK METAL. The year or so that followed this bewitching introduction—play the song yourself and tell me it wouldn’t hit on a heartbroken late-night off-campus stroll—saw me spiral, often beyond my control, down a rabbit-hole furnished by both Blunt and his mysterious cast of affiliates, slouched beneath headphones in laundry rooms, subjected to odd glares by roommates wondering what on Earth the shared room speaker was playing, humming along in bed to mantras I didn’t know the meanings of. As of the writing of this piece, as is also the case for Naked Lunch, I have the faint notion that this rabbit-hole might not actually have a bottom: the selling point of it all may really have just been the experience of falling. But there’s also the fact that my entire descent, and willingness to continue along the pitch-black path downward, was fueled by a futile desire to pretend that I had mastered the music, and not the other way around—exceeding a point where, in order to make up for my unsolvable naivete, I convinced myself that my own mind was humming the indecipherable tunes, and not Blunt’s unreadable silhouette.

Dean Blunt’s sonic luring game operates on the strength of broad cultural appeal, a peek behind the veil of which reveals uglier, more intense machinations. Though his activity can be traced as far back as the late aughts, a good portion of his American listening base was introduced to him in the run-up to A$AP Rocky’s ill-received 2019 album Testing, when the rapper, seemingly out of nowhere, released a slew of loosies either featuring Blunt or sampling his earlier work. The unlikely duo’s most popular collaboration, now streamed upwards of a million times on Spotify, is “19,” a deep-cut on Blunt’s 2020 LP ZUSHI that features Rocky and Sauce Walka on a bouncing backbeat that may as well have been illegally finessed from the cobweb-riddled secret vaults of DJ Screw. Listen to ZUSHI, as many did, in search for more like this, and one is instead met with echo-heavy phone calls, amateurish acoustic guitar pluckings filtered through reverb pedals, and overly-distorted electric guitars stumbling, wordlessly and hauntingly, along menacing power chords. Some of the most compelling Dean Blunt tracks are the ones that ask you how much you can take. A day before ZUSHI’s release, he surprise-dropped “STALKER,” an hour-long single many thought to be a cleverly-hidden album until they realized that it was just a 60-minute loop. “I’ve been watching you,” Blunt says through the sampled voice of a Black female lead, and you get the feeling that he’s been laughing, too.

“Do you listen to Dean Blunt? No? Ok leave (100 emoji)”

In the few weeks that spanned between Naked Lunch’s appearance on my bank statement and the curious first few moments I would actually spend with it, I received an apologetic note from the bookseller, a man named Bill, via email. “Samuel, As the day is coming to an end, I realize that I do not have this book,” it read. “I have looked hours and hours for days, but am unable to find it. The only copy I have is newer and looks the same–but it is a later copy.” The industry of book collection has long been an enigma to my too-lazy mind, and Bill’s perceivable mistaking of me as an older book collector reminded me, in that moment, of an awkward conversation I had endured on a recent flight from New York. With about an hour and a half of sky time to catch up on a 40-page reading—due for a class I would only have time to speed-walk to once I arrived on campus—I skimmed through several chapters’ worth of autobiographical insights until, upon the arrival of the snack cart, a heavy-set man seated directly beside me jumped at the chance to prompt a long conversation about what I was reading. The man was a white-haired, bespectacled book collector en route to a friend’s funeral, and it seemed like his overt giddiness was only a front for darker feelings that would only begin to surface over the next few days. But I was now the impromptu stand-in cushion for his existential spirals, and between catapults of bulky saliva flecks towards my face, he spoke, ad nauseam, about the thrills of receiving early printings of classic texts, Sonic Youth’s place in New York City’s No Wave Movement, and his liberal son struggling with a conservative campus. What I felt then was quite similar, if not the same, as what I was feeling now, with Bill’s apologetic email sitting stagnantly on my phone: I would have been intrigued had I known what he was talking about, but the double gut-punch of obscure works to be decoded and little time to decode them pushed it all in through one ear, and swiftly out the other.

Sonically, the role of saliva-spitting confusion-peddler was also played, in the time I spent waiting for my copy of Naked Lunch, by the deluxe version of Roaches 2012-2019, a gluttonous genre-spanning record Blunt would release, silently as always, in 2020. Every song on Roaches, it seems, could be the work of an entirely different artist. The LP is littered with various ostensible mini-projects—a stint like “NITRO GIRLS,” for instance, features four similar-sounding tracks in a row, respectively titled “NITRO GIRLS 1,” “NITRO GIRLS 2,” “NITRO GIRLS 3,” and “NITRO GIRLS 4”—each of which contribute to a lurking sense of displacement, waiting to be threaded together by Blunt’s commanding presence, but fatally left to starve by his preference to glare teasingly from the fringes. The coping process, for me, first entailed clinging to the few lyrics Blunt actually sang; when that wasn’t enough, I began following an exaggeratedly-conceited bot-operated Twitter account dedicated to hourly exultations of him. It made more sense to deify Blunt than to make an impossible attempt at understanding his craft, and so, eventually, I, too, began tweeting things along the lines of “I wish Dean Blunt would slap all 11 year old upright bass prodigies from Poughkeepsie New York,” “I wish Dean Blunt would slap all endangerments to the rodent community,” and “Do you listen to Dean Blunt? No? Ok leave (100 emoji).” I had convinced myself that Dean Blunt was my favorite artist, when really, he was the one I was trying hardest to understand. His lack of reciprocation—and the knowledge that any such reciprocation would never come—made me fight harder than I was willing to admit to feign as if he was within reach the entire time.

“I’m off on the merry go / your girl ordinary,” Blunt’s lazy voice sings with obscurity on “LIT freestyle,” buoyed by the comically-upbeat melodies of Prefab Sprout’s glossy 80s-pop hit “Cue Fanfare.” “You know that I’m coming. I know that I’m going.” His limited vocal range furnishes his pitched-down sample-tracks with a certain menacing undertone, ghastly like the hums of drug dealers who may as well be ghosts. Sparse as its serving size often is, it is only a matter of time until you convince yourself that the humming is coming from inside your own head.

💊💊💊

“A coprophage calls for a plate, shits on it and eats the shit, exclaiming, ‘Mmmm, that’s my rich substance.’”

At some point in Naked Lunch—still not even fifty pages in—we are met with the chaotic prospect of hundreds of escaped IND’s (persons suffering from Irreversible Neuron Damage) wreaking havoc upon the streets of the Freeland Republic. “Amoks trot along cutting off heads, faces sweet and remote with a dreamy half smile,” Lee reports. “Religious fanatics harangue the crowd from helicopters and rain stone tablets on their heads, inscribed with meaningless messages… Leopard Men tear people to pieces with iron claws, coughing and grunting… Kwakiutl Cannibal Society initiates bite off noses and ears… (…) A coprophage calls for a plate, shits on it and eats the shit, exclaiming, ‘Mmmm, that’s my rich substance.’” It took me several days after my first time cracking the book open to reach this particular moment, and when I did, I didn’t really feel anything. Naked Lunch’s genius lies, partly, in its acute ability to desensitize you: much like the Hell it claims to plunge its readers into a sobering tour of, there is no shortage of death, pain, nor the grotesque, and at the moment you think you’ve had enough (7 pages), there is an eternity (200 plus) more to be unraveled.

I had originally planned to leave Dean Blunt alone after listening to—and being confused by—BLACK METAL and its 2021 sequel BLACK METAL 2 on back-to-back late-night walks, both furnished by big-city lights and hordes of drunk pedestrians having a much better time than I was. My freshman year of college brought on an existential dilemma that, with snowballing valiance, I sought to soothe via futile attempts to wrap my head around lofty, too-grand concepts. As winter break drew nearer, and the time came to make plans with people at home so I wouldn’t have to confront my loserdom, the art world grew into an attractive enigma I desperately wanted to decode for the sake of both cool points, and the ability to say that I had understood something I set out to understand. With my best impression of ritzy gallery lingo, I texted a SoHo sculptor I had interviewed the previous summer to schedule a “studio visit” (I still do not understand the meaning of this term) for 10 AM on a December Tuesday. “10AM!!! Lol,” he replied. “How about 2pm- I’m always focused on work in the morning so I can put my thoughts into potentially monumental works (hugging face emoji).”

“Can I caress this……. girl?”

When 2 PM came that Tuesday, I pressed the graffiti-obscured buzzer bordering his studio space to no reply, then waited, for an hour or so, in the cold of a nearby park populated by brave pigeons and small-talking tourists. In one shivering hand was a copy of Greg Tate’s Flyboy in the Buttermilk—another obscure text I had freshly begun attempting to wrap my head around—and in the next, there was my phone, open-faced in hopes of an apologetically-toned text message telling me I could come inside now, or a just-as-apologetic phone call poised to tell me the same thing. I was already wiping my nose down the steps of the Canal Street Subway station when the call came, and upon making the blocks-long pilgrimage back to square one at the buzzer, found myself following the artist up his futuristic spiral staircase lined with old New Yorker magazines and unfinished paintings. “So what is it, break time now?” he asked, sounding like an absentee father, midway through a firm hand-clasp.

We never really did hit it off. Several times, I accidentally stumbled into in-progress paintings sprawled across his floor, and noticed, beneath his profuse reassurances that things were cool, an annoyedness that made me wonder more and more what I was doing at his place. When his landlord, a sturdy middle-aged man with a thick Italian accent, walked in unannounced and castigated me for not taking my sneakers off in his building, I thought he was joking, so I laughed—a decision that prompted one of the most awkward silences of my life. Luckily, somewhere down the line, the mounting ice was temporarily broken by the surprise-arrival of Max Blagg, an old British beat poet the artist had befriended over the previous year. While I gradually zoned out of their conversation, which, perhaps on purpose, was drawing further and further beyond my level of comprehension, I began paying more attention to the music playing on a nearby speaker. Through the device, and over monotone yaps about vacant residential buildings, came “Direct Line 2,” a somber track in which Dean Blunt, between walkie-talkie cut-ins featuring ebonized female dialogue, languidly asks an unnamed woman for permission to caress her. “I’ve been alone in here,” Blunt sang darkly, as the two artists delved deeper into a discussion long gone over my head. “Can I caress this… girl? Can I caress this…… girl?”

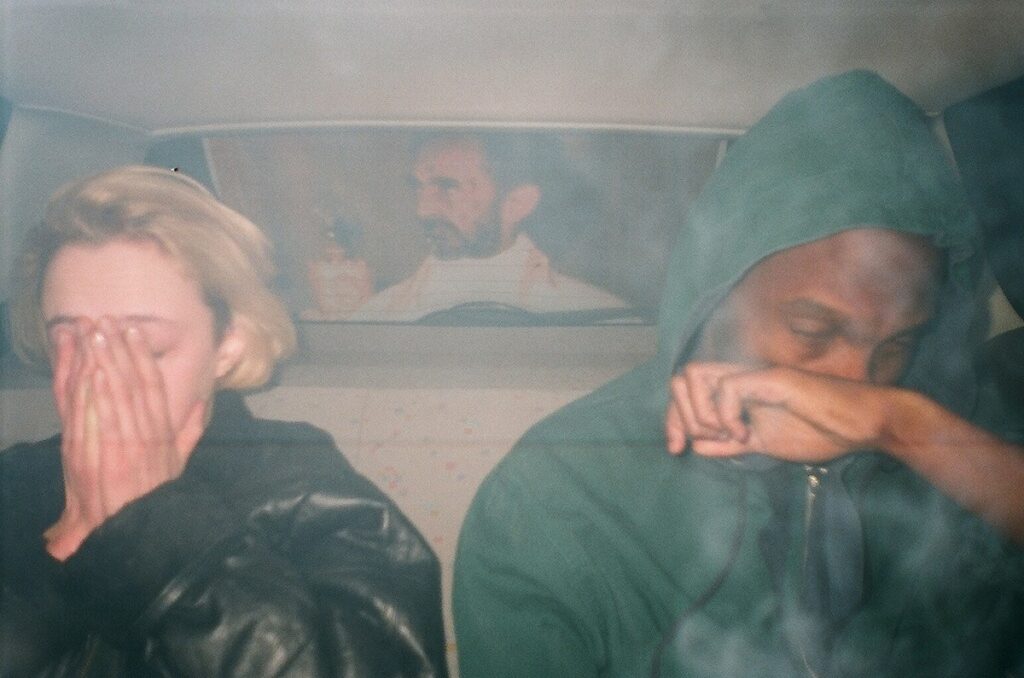

Much like that one meme where Barack Obama awards himself the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the first quote on Naked Lunch’s rave-review-dedicated back cover is a quote—or, rather, a disclaimer—by William S. Burroughs himself. “There is only one thing a writer can write about: what is in front of his senses at the moment of writing,” he muses, ellipses seemingly added for dramatic effect. “I am a recording instrument… I do not presume to impose ‘story ‘plot’ ‘continuity’… Insofar as I succeed in Direct recording of certain areas of psychic process I may have limited function… I am not an entertainer.” Interestingly, as much as his reclusiveness makes him unavoidably entertaining, Dean Blunt, too, operates on a similar fulcrum—his work seems more a steady attempt at cataloging his twisted machinations than making them palatable; the resulting audience is a liability before it is a reward, and his confusing footprint might just be a two-pronged attempt to both punish and demean those willing to stick around. In his most notable public stunt to date, he hired a paid actor to accept his NME Philip Hall Radar Award in 2015; two years later, in a controversial New York concert that could just as easily have been a performance art showcase, he set the venue’s temperature to 80 degrees, filled it with fog, then had prolonged bass barrages played at ear-splitting volume. His escapist tactics feel just as much like a respite for him as a repellent for his followers. “I make sure the place is too smokey for me to even feel anyone else being there,” he said of the New York show in one of his sole interviews to date, six years ago. “And so I can smoke.”

You never really do stumble upon Dean Blunt—perhaps Naked Lunch, either—on your own, and the web of affiliated artists he’s both buoyed and been buoyed by pose contradictions to him as interesting as the music that results. Among the most question-raising products of the dynamic is “Chancer,” the A$AP Rocky-featuring opening track to his succinct 2018 record Soul on Fire. The song is comprised by an increasingly-aggressive Rocky shouting, with varying levels of vehemence, towards the quiet void occupied by the London provocateur. “Ay Dean, let these niggas know what the fuck is up,” he starts. “Only London nigga out here smoking blunts back to back like a fucking yankee, nigga. To the front, ya heard? Niggas wanna hate you when you down. They doubt you when you doin’ it.”

“I’ll wipe your ass, I’ll wash out your dirty condoms, I’ll polish your shoes with the oil on my nose…”

Blunt’s response is jarringly monotone, his lowly voice casting all sorts of wicked shadows over the descending violin pattern soundtracking the unlikely sonic scene. “I ain’t even gotta try that hard,” he sings gravely, sounding ever-so-slightly like he’s reading off of a sheet. “(…) They just wanna stop us getting rich. We ain’t gonna take no more of it. So if they gonna shoot they better hit, hit, hit.” In the twenty or so seconds of screamed A$AP Rocky ad-libs that bring the track to its close, it’s easy to forget, amidst the rapper’s brazen threats, that Blunt was ever there. But before you can start thinking about it, the song is over—probably the album, too (it’s only 13 minutes long)— and none of it matters as much as you thought it did.

Within twenty pages of Naked Lunch, we are introduced to a hopeless junkie who bleeds green blood and performs unspeakable sex acts with figures of authority. At some point, he finds himself begging on his knees for mercy upon realizing that he has been caught, and is in grave danger of being fired. “Please Boss Man,” he pleads to a higher-up, drunkenly shoving the poor listener’s hand into a toothless mouth. “I’ll wipe your ass, I’ll wash out your dirty condoms, I’ll polish your shoes with the oil on my nose…”

Despite his begging and pleading, the man is met with revulsion, and sent to court—where, due to the hilariously fucked up nature of the novel, he is released regardless of the “Boss Man”‘s mysterious death. (The aforementioned begging scene was the last time anyone ever saw him alive. ) Whether our frantic prayers be to obscure artists, obscure literature, or obscure ideas, we’re very much the same when it comes to mystery—foaming at the mouth for access to something that was never ours in the first place—until it inevitably forces us to be the judge and reckon with ourselves. With the amnesty we are granted by the courts of our own conscience, we resolve to convince ourselves that our own minds are humming the tune.

2 replies on “Death, Dean Blunt, and Naked Lunch”

got damn!

my mind is obscured by the tune we’re humming…