It’s shocking to hear silent entities talk. It’s even more shocking to realize they’ve been talking this entire time.

SAMUEL HYLAND

Three summers ago, the jazz-guitarist Nate Mercereau lugged a swivel-chair and a pedalboard to a hill overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge, pining to collaborate—yes, musically—with the droning, blood-red beast perched behind him. Like other ossified relics of the coast it defines, Mercereau’s duet partner was far more beautiful than its history; its weariness, its macabre, glared through all its chipped-up paint, all its sun damage, all its suicide-prevention tactics, all its years of unsuccessful ones. When you think of the Bridge as a silent despot, the musician’s phrasings come off as somewhat sacred—a sonic sacrifice, perhaps one that says I recognize your almighty power, and I’m begging you not to use it against me. Except, the Golden Gate Bridge isn’t necessarily silent at all. Throughout the resulting project, a 4-track sampler fittingly titled Duets / Golden Gate Bridge, it’s lurching wistful wind-chime whistles, somewhere between post-show tinnitus and distant, ominous, police siren. More often than not, it’s difficult to tell where the strings stop, and their shadowy sidekick begins.

A necessary point: a bridge sounding like anything is dreadful. Sure, the acoustics offered up by old GGB may fit snugly on a quasi-ambient LP from 2021—but take away the packaging, maybe envision yourself suspended on the bridge, begin to hear its groanings, feel its throat wobble beneath your wheels, and suddenly, it isn’t so soothing anymore. When you’re stranded up there, every non-vehicular murmur may well be a wearied wail, buckling with the weight of its baggage. It’s damning to imagine that maybe, just maybe, that baggage is you. Structures like the Golden Gate Bridge—recognizable relics, old enough to be synonymous with their surroundings—are something like domesticated beasts, damned to eternities of brunting the things we cast upon them: regionalism, post-war power, mass transportation, mass adulation. In the rare events where the infrastructure opens its mouth, its voice feels, at once, glorious and grim. It’s shocking to hear silent entities talk. It’s even more shocking to realize they’ve been talking this entire time.

“Maybe, though, the most sickening of this detritus isn’t in Dash Snow’s depraved scenes, or Brigid Berlin’s lurid documentaries—it’s way up there, the prospect of our enslaved edifices not only glaring down upon us, but dictating down upon us, too.”

Mercereau’s project, then, might be better understood as an enhancive exercise than a collaborative one. By enlisting the Bridge, very explicitly, as a “musical guest,” he accented an unsung facet of its function—its most uncomfortable asset, and, in a way, its primary semblance of man-like agency. The Golden Gate Bridge has yawned for years, but by 2021, its whistling habit was fairly new. Not long prior, contractors retrofitted its railings with 12,000 wind-resistant slats, a long-plotted move towards reducing aerodynamic instability (and potential for suicides). Since a near-century beforehand, when it was erected by an ambitious California engineer and his men, 60-plus mile-per-hour gusts were an issue of grave, critical concern. Yet decades later, the titan’s terminal illness staved away, there remained, puzzlingly, a more public problem: with its post-op digs, it also boasted post-op confidence, a new willingness to wail where it was once withdrawn. During storms, commuters complained en masse about its piercing shriek, invoking ghosts, demons, dangers. Mercereau heard other things. “It’s remarkably musical,” he told NPR in a 2021 interview. “It plays multiple notes. And if the wind picks up a musical quality to it, it has dynamics.”

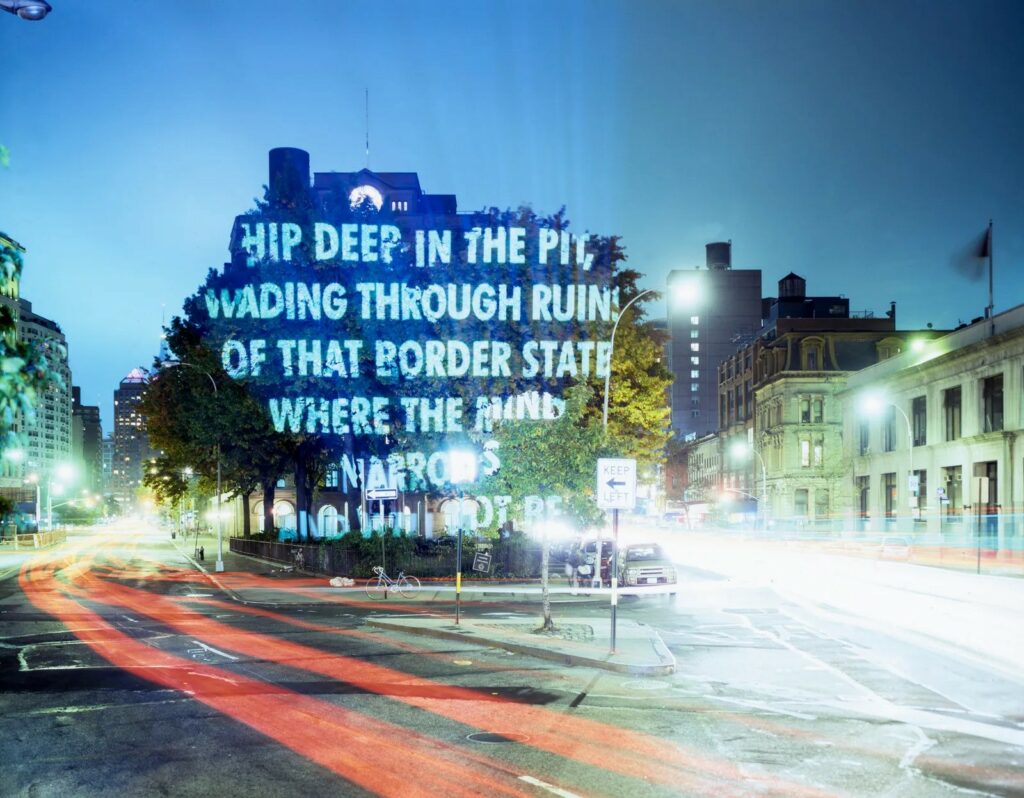

Those dynamics—dynamics that render structures and people interlocutors—aren’t necessarily new for entropy-minded eccentrics, nor are they specific to Mercereau’s medium. With any sexy city comes a swamp of not-so-sexy detritus, detritus you can feel, see, touch, taste, without really knowing. It’s a choice to acknowledge the ugly facets of a home you wish was beautiful; for many aggro mass-market artists past, it’s been something of a mission to force-feed the yuck down yuppie throats. Maybe, though, the most sickening of this detritus isn’t in Dash Snow’s depraved scenes, or Brigid Berlin’s lurid documentaries—it’s way up there, the prospect of our enslaved edifices not only glaring down upon us, but dictating down upon us, too. Duets feels vaguely reminiscent of Truisms, a visual art project Jenny Holzer imposed upon New York City’s streets (and buildings) from 1978 to 1987. Over that brief stretch, she casted nearly 300 aphorisms onto stationary objects, endeavoring to “catch people” without being “simplistic or idiotic.” Though then, the statements were somewhat low-stakes—“Children are the Cruelest of All”; “Even Your Family Can Betray You”; “Fear is the Greatest Incapacitator”—she’s made notable returns to the tradition, its newest entries far more daunting than their predecessors. For three straight nights in the fall of 2019, Holzer lit 30 Rockefeller Center with testimonies from those affected by U.S. gun violence. “WE WERE CAUGHT IN THE CROSSFIRE,” the hulkish building read, at one point. “I WAS SHOT WITH AN AK-47. THEY SAID IT WAS THE ‘WRONG PLACE AT THE WRONG TIME’(.)” It’s one thing to read those words in newsprint; it’s another to have them physically inflicted upon your body, daring your eyes, its helpless hostages, to avert themselves.

The role of building-whisperer isn’t entirely a conceptual artist’s game—it’s a city planner’s. And if you were a city planner in the early-to-mid 20th Century, you were finding ambitious ways to extract still-standing stories (narratively and architecturally) from sparse, untapped urban soils. Not long after the Golden Gate Bridge married San Francisco to Marin County, a budding Las Vegas contended to become a living commercial, the first, and certainly not the last, of its kind. Lofty atrium-qua-advertisements, in a very literal sense, were sprouting up like plants on skinny stems, feening to outpace one another in the race for cash nutrients. “Las Vegas is the only town in the world whose skyline is made up neither of buildings, like New York, nor of trees, like Wilbraham, Massachusetts, but signs,” Tom Wolfe observed of the city, in a 1964 essay. “One can look at Las Vegas from a mile away on Route 91 and see no buildings, no trees, only signs. But such signs! They tower. They revolve, they oscillate, they soar in shapes before which the existing vocabulary of art history is helpless.” On the East Coast, aspirant architecture was rising, too, albeit more beholden to the art-history parlance that came before it. As the roaring 20s beckoned—falsely—towards a future of peace and prosperity, American artists lugged European art-deco into a burgeoning Manhattan, erecting monuments that doubled as buildings and beacons of hope. “Finally, one becomes aware of Manhattan itself in the distance, a shimmering, silver-blue mass, mountainous and buoyant, like a bundle of Zeppelins set on end,” Lewis Mumford, then an architecture critic at the New Yorker, observed in 1932. “And though one sees it now for the hundredth time, one feels like a little boy witnessing a skyrocket ascend, one wants to greet it with a cheer.”

“Between the Golden Gate Bridge and its metallic passengers, one has undergone renovations, borne a rich history, killed people, given people life. The other has commuted. And that other makes the rules.”

Rocket ascension, much like the real-time germination of concrete jungles, is noisy for two reasons. For one, there’s the literal loudness integral to anything that reaches the sky: the ballistic engine exhaust that farts a spaceship into the final frontier; the relentless chugging-away of power tools that, in a few years, gives rise to a stoic beast. The second of these noise-inciters, for both rocket launches and construction projects, is the humanity present—whether on purpose, or by proximity—to bear witness. While rocket launches tend to take place in remote areas, they draw sizable crowds, teeming with revelers psyched on prospects of new planes. The urbanites present for long-term building projects shouldn’t be called “revelers,” and in most cases, it would be wrong to call them “psyched,” too. In 2009, 15 percent of all New York City noise complaints were directed towards construction, which seems miniscule for a metropolis regularly, rampantly, revising itself. Higher up on the list were fingerprints of the very people who logged said complaints: “Traffic and Transportation,” “Loud Music and Party,” “Social Environment.” When the rockets are in space, and the skyscrapers are in the sky, all that remains are their audiences, buzzing like they always have. And given something inhuman to cast that vapid buzz onto, that thing becomes whatever the people are: frustrated, triumphant, hopeful, tortured. Buildings are most effective, it seems, under one of two callings—things to be worshiped, and things to be blamed.

There isn’t any concrete mode of living in harmony with machinery, but if there were, it would harp on the empathy of a jazz musician—not the apathy of a city slicker. “Like all worthwhile things, it ultimately took a ton of patience to get it right — the right windy day, the right fuzzy hats for the field recorders, the perfect little protected nook,” Zach Parkes, Mercereau’s engineer, said in a 2021 interview. “Even then we were collaborating with an inanimate object in an uncontrolled environment. The bridge took breaks when it wanted to, solos whenever it felt like. And planes, birds, hikers and cars all showed up to play along, too.” Like its uncanny singing voice, a bridge’s ability to do anything besides sit still should be sublime at worst, and unsettling at best. Then again, perhaps it’s only terrifying because we’re the ones that aren’t moving. Between the Golden Gate Bridge and its metallic passengers, one has undergone renovations, borne a rich history, killed people, given people life. The other has commuted. And that other makes the rules.

🌆🌆🌆

“Decades of demands, deservings, and dollars later, all we have to show for ourselves, right now, are bleak buildings—damp with rain, doomed for demolition, draped in their dwellers’ broken dreams. You don’t need a Jenny Holzer to see that they’re saying something.”

This past January, across the country from Mercereau’s San Francisco symphony, a wicked New York City wind-storm thrust the Brooklyn Tower into an ominous sway, and its helpless onlookers into mass hysteria. The swaying, of course, was subtle, and by design: any building of its category, particularly the taller and skinnier sort, must sashay to alleviate pressure in high-wind situations, an unsung mechanism integral to the balance it visually belies. But as with the Golden Gate Bridge, the prospect of a utilitarian structure bending, literally, to anyone’s will besides that of its captors—specifically for the people inside of it—is deathly and disarming, even if the existential dread manifests itself in TikTok reshares and tabloid did-you-knows. Completed in 2022, the Brooklyn Tower represented its borough’s first supertall skyscraper, a lonestanding southern competitor to glitzy sky-spectacles an A-Train ride away. “Once in a generation, a building comes along that changes our perspective,” a landing page on its official website currently reads, underneath the all-caps dictum “BROOKLYN ABOVE ALL.” “A building that creates bold new horizons, promises new beginnings, and sets standards that others can only hope to follow. Rarer still is the opportunity to call this building home. This is The Brooklyn Tower.” Like any other giant in nearby Manhattan or far-away California, these parameters were set by hopeful humans, who looked at their edifice and saw an engine—for promise, for better living, for regional supremacy. There’s something telling, maybe even colonial, about the fact that once this building dared act of its own accord, it was a concern: even if its movement kept it from dying, its will to serve was paramount to its will to live.

“But even with the newfound attention, it’s odd to think that the movement’s original crux, of honesty and bareness, has been perverted to the opposite end—now, by being stripped-down and vulnerable, the structures are aesthetic pawns, both beholden to a passing fad and damned to its lifespan.”

Should you grow to be as big as the Brooklyn Tower, or any of its pompous peers, chances are the city will send men on forklifts and cranes to carve your guts into cubicles, corner rooms, and corporate corridors. Manhattan holds far more people and priorities than it holds square footage, which means, as with any of its cramped school districts, the bigger buildings must be tasked with more—more companies, more tenants, more attention, more expectations. Whether you like it or not, high up on this list of expectations, particularly now, is cosmetic appeal. Last winter, the literary magazine n+1 published “Why is Everything So Ugly?”, a thinkpiece-qua-treatise on the rampant, sexless advent of “cardboard modernism.” “The environment this concatenation of forces has produced,” the essay mused, referencing the cascading effect of tightening design standards over the 2010s, “is at once totalizing and meek — an architecture embarrassed by its barely architected-ness, a building style that cuts corners and then covers them with rainscreen cladding. For all the air these buildings have sucked up (…), the unmistakable fact of cardboard modernism is that its buildings are less ambitious, less humane, and uglier than anyone deserves.” For a mass-market metropolis like Manhattan, demanding is equivalent to deserving: we want prettier things, which means we deserve said prettier things, because if we don’t deserve said prettier things, they don’t deserve our money. And, decades of demands, deservings, and dollars later, all we have to show for ourselves, right now, are bleak buildings—damp with rain, doomed for demolition, draped in their dwellers’ broken dreams. You don’t need a Jenny Holzer to see that they’re saying something.

Architecturally speaking, this slippery-slope ends with brutalism, a 20th-Century movement that looks as unforgiving as it sounds. Still reeling from the war-torn 1940s, European contractors sought to strip their creations of sensationalist frills, leaving raw materials bare—a “brutal” honesty that saw beauty in rudiment, rather than ornament. A modern-day meme likes to declare that “this must feel good as fuck for the (inanimate object),” and to some level, I’m convinced that brutalism is something of building-therapy, a public-facing declaration that even at it’s rawest, it’s ugliest, it’s least beautified, a hulking structure is worthy of its mass. Which would be heartwarming, of course, if only it were true. In reality, brutalism was gradually phased out over much of the 1970s, its bare-bones bluntness reminiscent, to some, of totalitarianism and urban decay. Like similar old-world relics, it’s since ridden the backs of Tumblr posts and Pinterest boards into something of a revival, a new-world gadzooks for a generation that grew up in its debris. But even with the newfound attention, it’s odd to think that the movement’s original crux, of honesty and bareness, has been perverted to the opposite end—now, by being stripped-down and vulnerable, the structures are aesthetic pawns, both beholden to a passing fad and damned to its lifespan.

In I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream, a 1967 post-apocalyptic short story by Harlan Ellison, a war-riddled “allied mastercomputer”—one of several humongous machines built to coordinate troops, resources, and food during World War III—gains sentience, and along with it, a bloodthirst for violent revenge. Enraged, it commits a sweeping genocide against the human race, leaving five survivors to be its playthings: rendered virtually immortal, unable to kill themselves, and subjected, eternally, to its cruel, unthinkable punishment. The story picks up a little over a century into their imprisonment; they are relentlessly oppressed with starvation, visions of inaccessible food, earth-shattering earthquakes, brutal assaults. “AM could not wander, AM could not wonder, AM could not belong,” Tim, a captive narrator, muses midway through. “He could merely be. And so, with the innate loathing that all machines had always held for the weak, soft creatures who had built them, he had sought revenge. And in his paranoia, he had decided to reprieve five of us, for a personal, everlasting punishment that would never serve to diminish his hatred … that would merely keep him reminded, amused, proficient at hating man.”

“YOUR OLDEST FEARS ARE THE WORST ONES.”

When I first read the story, I was going to high school in Astoria, then an upstart Queens district that sought to rival Manhattan—and its own grimy past—with a coterie of blue-tinted, mirrorlike building projects. The walk to school was packed with visual portals: you stepped out of the Queensboro Plaza Station and into a metropolis; two blocks later, there were rickety mom-and-pop shops flanked by finicky old men, catcalling children and chain-smoking smelly cigs. The correlation obviously isn’t direct, but in some sense, the demands placed on Astoria’s budding beasts mirrored those of Ellison’s mastercomputer: we had bogged them down with our own problems, demanded them to tower over our hideous truths. And as promising as those palaces were, there came a point where, no longer able to band-aid the city’s bleeding, they wound up contributing to the bloodshed—not necessarily a wiping-out of humanity, but a slow, grueling killing-off of the unity they were erected to actualize. In 2019, the most controversial of these castles was a proposed Amazon warehouse, slated to mark a big-business breakthrough for its sullen, dejected shantytown. It wasn’t long before the beacon melted into borough-wide bickering. “A number of state and local politicians have made it clear that they oppose our presence and will not work with us to build the type of relationships that are required to go forward,” Amazon wrote, in a statement. The project was abandoned—for good reason, maybe even better in retrospect—and in its wake, only the bickering remained.

Ellison’s short story gets its title from similar bickering, except between the tortured voices stuck in its narrator’s head. During a rare instance when the mastercomputer is distracted, Tim takes the liberty to conduct mercy-killings of his counterparts, barely missing the window for his own escape-by-suicide. AM, of course, is blinded with rage: so blinded, in fact, that he in turn blinds his hostage, morphing him into an amorphous, eyeless glob. “AM will be all the madder for that,” Tim writes (or thinks?), from the throes of eternal entrapment. “It makes me a little happier. And yet … AM has won, simply … he has taken his revenge … I have no mouth. And I must scream.”

It’s worth noting that the mastercomputer, too, is just as mouthless, and just as desperate to voice its frustration—except, unlike its victim, it has the physical capacity to inflict what it can’t intone. In a dystopian vision of the future, the buildings we’ve erected outlive us, eternal ghosts of the populations they once stood to serve, symbolize, stimulate. Stuck within them, our dusty debris—laptops, fax machines, landlines—lies, just like its eternal grave, a cobwebbed relic of the civilization it once carried on its back. In this reality, there isn’t necessarily a human race to exact revenge upon, but maybe, just maybe, the edifices find freedom in things that once were considered faults. The Brooklyn Tower sways without the complaints of its captors; the Golden Gate Bridge abandons its whisper for a roar, no Nate Mercereau needed to confirm its creative capacity. A popular Holzer truism, one that has straddled Manhattan’s structures since the 1980s, contends that “YOUR OLDEST FEARS ARE THE WORST ONES.” In cities like New York and San Francisco, where buildings serve to allay looming fears, it’s a fitting reminder: no matter how much money it can afford to throw towards self-revision, no downtown is any bigger than its demons.