Vinyl Williams Will Show You the Galaxy.

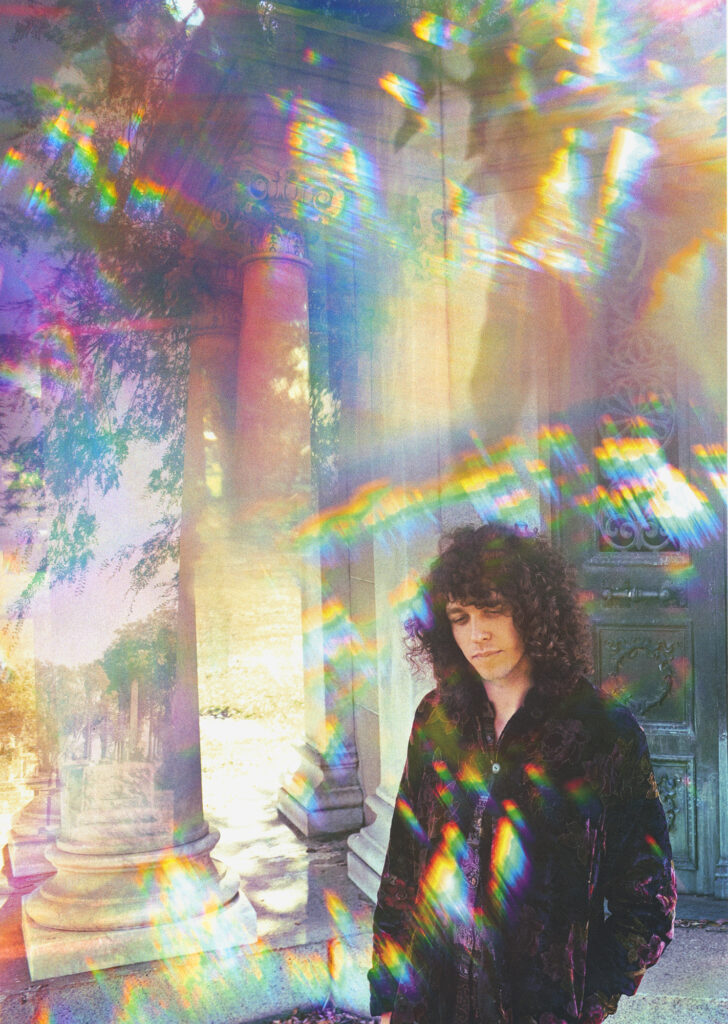

Lionel Williams’ belief in the celestial manifests itself in music that sounds endless, impossible, and comforting all at once. (Assorted throughout the article are art pieces from various projects by Williams).

SAMUEL HYLAND

The musician Lionel Williams is a firm believer in the power of the universe. One night last year, resting mid-tour in an Oregonian cabin, he lived through one of many testimonies he’s garnered of the concept – attempting to show a friend of his the intricacies of a certain song, his avenues of argument were undoubtedly few at the outset. “There was one song I was playing by this band called Montage, a 60s LA band, and it was last year on tour,” he says, chatting with me shortly after an impromptu studio session. “The song is so . . . it’s just two minutes, but it’s practically concentrated bliss. So I played it for my friend Alan.” As soon as they ventured outside, the universe stepped in. “I’m like Have you ever seen a UFO out here? It was night-time. And he’s about 50 years old or so. So he says No, I’ve never seen a UFO in my life. And as soon as he said that, we saw this blue diamond appear in the sky, that made a half-crescent and then disappeared. I was just like, What- was that? And he’s like I can’t explain that. I have no idea.”

A lot of what cannot be explained naturally, Williams finds, is explained by invisible wormholes, black holes, and celestial bodies that intertwine all things existent in the magnetic field. Music is an omnipresent factor to this cycle. Amongst various other testimonials of such nature, a standout example he comes back to time and time again is the sensation he receives upon listening to specific tracks. The first times he listened to Toro y Moi’s first and second studio albums – Causers of This and Underneath the Pine – on good speakers, there were distinct bodily reactions that only could have possibly been borne from those particular circumstances. “There were chills happening from my arms, to my legs, to my feet,” he says. “I wasn’t necessarily listening, but my body knew that it was good.” Confirmation of the universe’s role in it all came in the form of Williams playing the exact same music for his friends. A song for which the chills were quite strong for him was Got Blinded, a deep cut buried six tracks into Toro y Moi’s second LP. Upon showing friends of his the song on the same setup he had experienced it through, he was shocked to find that the sensation was constant. “I’d show that song to them, all the way through, on really good speakers, and they would get chills. And I wouldn’t tell them about the chills (that I felt). I’d just show it to them, and they’d be like Whoa, I got the chills. And I’d be like That’s how I know it’s the universe!”

A day ago, when we were originally supposed to have our interview, I waited an hour to see him before rescheduling. Over text message some time later, he explained the situation: he had been recording a band in the studio, and legitimately lost track of reality (the entire session, he reveals in our chat, lasted 8 hours with no breaks).

Where most artists would lose track of time, it’s no surprise given his music that Williams often loses track of the line separating fantasy from the tangible world. Under the moniker Vinyl Williams, adopted from a nickname given to him by his co-worker Ernie at the Avalon Theater in Salt Lake City, he creates sounds that have garnered mass popularity for being immersive, ambient, and multi-dimensional. Playing alongside him in the musical act are longtime friends Nathan Najera, guitar, Spooky Tavi, also guitar, and Sam Chown, drums. This past June, they released their fifth studio album Azure – a 38-minute collection of atmospheric music that seeks to seduce one’s soul into harmony with what exists beyond planet Earth.

Screenshots from Kairon; IRSE! – White Flies

The goal of such art, Williams tells me today, is to provide an appealing gateway through which a spiritual experience is further palatable. A figure he cites often is Iasos, the Greek-born artist who pioneered the crossing of celestialism and mass-produced recordings. Although Iasos made music that would change your life given the chance, one would likely never experience it, because there was no clear entry point offered to the mainstream; as genuine as the sensation was, it was (and still is) virtually impossible for you to hear it playing in a CVS, or on car radio. Williams is adamant about seeking to install the portal Iasos overlooked – not for popularity – but for the sake of inviting the general public into a heaven that was once reserved for music nerds and devoted theorists.

It’s the latest point on a lengthy journey through sound that started when he was young. Born to a family boasting John Williams, the famed cinematic composer, Leah Williams, the classical pianist, and Mark Towner Williams, the drummer and producer, Williams started playing the grand piano when he was five years old. From there, he moved on to drums, after which he picked up the guitar. At 15, he recorded his first album with the help of his dad – a record he laughs about now – wherein his playing was a seismic shift from the jangly arpeggiations he exhibits today (“I was literally just playing metal”). But even more so, in music class in high school, seeds of diversion from his classical roots manifested themselves in tandem with what psychedelia he had just begun listening to. Having forgotten everything he once knew on piano following a years-long hiatus, he found that he was able to naturally come across sounds he couldn’t have discovered in any conventional sense: “Because I forgot everything, I found these weird new chords that my ear wanted,” he says. He had a band, then – an early version of the act he currently performs with – and it was through playing alongside them, listening to new sounds, and experimenting with the ones he already knew, that he laid the groundwork for what surreal dreamscapes he’s been known to conjure up to now.

“Every single person gets a tiny little glimpse of a wormhole, and it can come out in so many ways.”

Over all twenty-something years of this process, the sole steady variable has been consistent improvement. The way Williams reached the summit he sits upon bore just about everything that comprises a perfect rock and roll autobiography: Hefty risks; packed tour buses; tricks, schemes, loopholes. “We were two bands in a cargo van, with two bands’ equipment and no trailer,” he says of his first tour at 17 years old. “There were like, seven people, and there was so much stuff. We were literally like sardines in there. It was the summer of 2007; it was 115 degrees in Vegas, it was crazy. But you start there – and every single time it just gets better.” The next few tours that ensued, all of them while he was a teenager, were sneakily booked by Williams himself: he had worked an internship where one usual task was to field emails from professional bands and their booking agents, eventually getting a feel for the corresponding lingo. Soon, he adopted a fake name in hopes of trying it out himself. “I just copy pasted that – except with lower numbers, advances, guarantees – into messages like Oh I’m Thomas Asiano, I’m their agent. They’d think we were legit because I was ‘part of an agency,’ and they would book the show.” On his first tour doing so alone, it worked forty times.

Williams pursues a similar risk-ridden endgame as a visual artist. As part of the Los Angeles based non-for-profit art collective Non Plus Ultra, he orchestrates psychedelic performances, partakes in fifteen-person jam sessions, and occasionally goes live for national viewers (he actually has a live stream to get to right after our chat). Moreover, his visual art, although unintentionally so, is an uncanny reflection of his deep reverence for the powers invested in our galaxy. A visit to his official website puts this in perfect perspective: press ENTER on vinylwilliams.com, and the first thing that pops up is a pagewide map of some colorful, otherworldly, ancient-eque terrain — within a few seconds, the user is automatically transported to a point within the entire thing, as if they’ve zoomed in on planet Earth from a satellite to see one single street. Suddenly, the page is three-dimensional. The computer mouse becomes a navigation tool, leading the way through infinite paths and corridors of what cosmos Williams has manifested.

Screenshots from Foxylight – Past Vision

The mask of surrealism additionally extends to every album cover he’s worked on. The artwork for Lady Tiger, a single off of his latest project, consists of – amongst other things – an endless upside down staircase that leads into itself, disembodied limbs that seem to float through circular portals of golden yellow light, and an ominous black creature lurking behind a near 360-degree crescent moon. As for Azul Verde, another 2020 project, not much is decipherable within layers of physical matter – but is it meant to be decipherable in the first place? The canvas is covered in what looks to be a translucent body of water, an army of cloud-enveloped, silhouetted wildlife in the upper left hand corner, and a big-bang-reminiscent explosion of white noise at center.

When I mention that I get the same sensation from both his musical and visual art, he is insistent that such harmony is not put in place by strategy of any kind.

“It is completely non-intentional. The music isn’t intentional, and the art isn’t intentional,” he responds with a quickness.

This answer seems to invoke a passion in Williams. He’s shifted his sitting position, ever-so-slightly raised his tone, leaned a bit forward.

“I mean, the only intention for the music would be that it’s beneficial for the body. But the music and the art . . . they happen. And whenever they happen, it’s the same. They look the same, they sound the same – they’re the exact same. And it’s only when you remove intention, that that happens. Which is crazy. A lot of people have criticized my art, because of its lack of intention. And the thing is, that it’s not saying anything. It is a place that you can inhabit. It is a place that happens automatically. It is exactly what I want to see, and it is exactly what I want to hear.”

Something that Mr. Rogers really understood is that you don’t have to learn through a Bible and a belt. You learn through acceptance and comfort.

When Williams cites being artistically automatic, he’s referring to a lifelong string of creative imagery that has fascinated him since childhood, an unchanging fountain from which all of his ideas flow up to this very instant. If this string is of a yo-yo, his mind the hand and his creations the ball, the universe is the yarn that fuses the two together. In conversation, he recalls instance after instance of intergalactic mental foundation; many of the sightings are in things that, to everyday people, are trivial to the eye. Religious structures are some of these vessels. “This is a funny example, but it just happens to be at SeaWorld San Diego,” he starts, explaining one occasion. “There’s this Turquoise Mosque Palace rollercoaster. And it is- this must exist in another dimension. It struck me as so beautiful. And when I saw that, I was like: That’s exactly what I see when I close my eyes. When I want to make something. For some reason, it’s always been these Middle Eastern, or Hindu, or Indian-looking palaces, and rollercoasters, with a lot of different translucent pathways running through them.”

The point about pathways in Williams’ art is directly parallel to what I see when I pause mid-conversation to look up the rollercoaster he mentions. It’s a blue jungle of warped metal, with skinny tracks leading into dark thresholds beneath pointed domes, repeating the process a near-infinite number of times before re-emerging in a completely different remote location. For the split-second that the ride car is invisible, midway through what black hole carried it to its next cosmic location, a slew of questions naturally arise in the subconscious. What happened? How did it happen? Why did it happen?

Yet, these are physical issues addressed in Williams’ mind by exactly what the rollercoasters and temples happen to be examples of: the omnipresence of the universe.

“I think that there are wormholes everywhere,” he explains, spreading his arms as wide apart as possible. “There’s probably infinite (wormholes) crossing your body right now, and you don’t even know it. But there’s a way to access them here, in the physical world. Every single person gets a tiny little glimpse of a wormhole, and it can come out in so many ways. An infinite variety of ways. But really, what that is – is seeing the impossible overlay the natural world.”

Williams goes on to cite that every human being in the world experiences the impossible at least one time. These rare occurrences, he suggests, are the universe reflecting something about oneself that needs to be unknotted.

All people, whether knowingly or unknowingly, hold such inherent truths that need unknotting. They are carried with us no matter how far we travel from our origins, no matter how long ago our most recent memories of them faded away, no matter whether they will wind up having helped us or hurt us when we close our eyes. For him, much of those truths unravel from the way he grew up. Up until he was eight years old, he was raised in Los Angeles, attending Jewish private school there. He moved to a highly religious – Mormon, to be specific – section of Midway, Utah afterward, where he recalls having attended church seminaries as part of the average school day (“Now I’m thinking Where’s the separation of church and state here, guys!?” he says, behind a laugh).

But being exposed to as many ideologies as he was exposed to, just as much as it opened his eyes further beyond himself, forced him to look inward perhaps even more. Being Jewish, he was subject to several encounters of belief-based bullying in the Mormon school he attended.

“I remember being bullied a bit, and then I realized: I would never ever dislike somebody because of their religious preference. And that’s just the plurality, how everything is reactionary with how we learn,” he muses. “I don’t think that learning always has to be so dark, though. Something that Mr. Rogers really understood is that you don’t have to learn through a Bible and a belt. You learn through acceptance and comfort.”

“When you really start to just forget about any worry, you can completely get lost in that zone.”

The latter principle rings true to all that Williams creates across artistic mediums: he wants to accept you into a once-inaccessible otherworldly intrapersonal realm on behalf of the universe, and – through whatever sensation you get from his output – comfort you into wanting to stay.

The Bee Gees are an exact model upon which he bases such aspirations for his music’s impact. “I’m not a huge Bee Gees fan, but I know their music comes from such a pure, earnest place – because I was thinking: how many people’s lives have they saved with their music? I would say tens of millions of people in the world over the last forty or fifty years, they’ve heard the Bee Gees and they’ve realized that life is worth living.” The next thing he says is a prospect for artists in both the age-old decades the Bee Gees dominated, and the completely different musical scope of modernity: “Their music is like a program for the mind, to make you feel good.”

The universe can fit into a flash drive. As enormous as it is in the sole common imagination we have been trained to exhibit, much like our very planet, its largeness is relative to whatever it is viewed alongside with. Earth is gigantic, side-by-side with the average human being. Throw Jupiter into the equation, and Earth becomes miniscule. Introduce VY Canis Majoris, and both planets are less than invisible.

Yet in the case of the universe, take away all of the size comparisons, and you are left with one singular entity. There is nothing left for it to be matched up against – it is, frankly, everything that exists as of this moment, everything that has existed in the past, and everything that will exist in the future. For this same reason, it is as small as you want it to be. Small enough to be crumpled into a formula of 0s and 1s. Small enough to be stored within a USB. Small enough to be transferred, like a computer program, into happiness for the human mind.

The only thing that can stop this process from occurring is the sole thing that could ever possibly top the universe in magnitude: the impossible. It is the impossible that, when already present in the mind, rejects any idea that the universe can inhabit what wormholes exist within it. There is nothing the universe can do to overrule such measures – and, unfortunately, the impossible is what prohibits many of us from tapping in with what exists beyond ourselves.

For Williams, if there is any one mission statement for what art he has spent his life creating, it is the permanent deletion of ration, logic, and this “impossible.” Whether arpeggiating eclectic guitar chords through a VHS camcorder, working on album art that stretches the limits of fact, or traveling across the nation by permission of only a fake name and a memorized email formula, he’s here to prove to you that the universe is indeed within reach – and he isn’t afraid to pull the curtain.

Prior to our interview today, Williams once again briefly lost track of reality. After having left his computer in the studio for a Non Plus Ultra live stream the previous night, he resolved to record some guitar parts for a song by Emerald Isle, another act he’s involved with – eventually winding up fifteen minutes late to our agreed meeting time. For him, reality is elusive in a way that isn’t necessarily problematic. He’s not wandering the streets of LA babbling unsolicited boxing advice to passersby of local 7/11 stores. It’s more like a casual slip-up – Oops, I left the stratosphere again! – that he makes all the more worthwhile by reporting his findings back to Earth through what he creates.

“I think when you remove yourself from the center of the equation, it’s easier to get lost in this realm,” he says. “For my own stuff, when I record, I definitely get lost- but it’s just like everybody’s process, where you just have to trust yourself. And when you really start to just forget about any worry, you can completely get lost in that zone.”

It’s impossible to predict what he may find while he is lost. But if we happen to remain in touch with the magic, we may just see a UFO – at which point his work is done; and, all that’s left to do is to find the magic within ourselves.