Why Don’t You Make Songs Like the Beatles?

Sweet Trip’s 1995 LP Velocity: Design: Comfort is living proof that true creativity often comes with a hefty price tag.

🔊🔊🔊

SAMUEL HYLAND

The digitization of music has presented a conflict since both worlds merged: if sound is an omnipresent element of nature, how could one be able to pause it, sell it, organize it in verse-bridge-chorus uniform, or turn it into an industry? In past lives, music consumption existed primarily in the sphere of live performance, with records being bought mainly for either ambience or collection. But with advancements we’ve seen in technology and the way music is presented, we now have at our fingertips the ability to do with sound what proves impossible with separate natural matters – pause, sell, organize, industrialize.

Surface-level, Sweet Trip’s 2003 release Velocity: Design: Comfort comes across as the dramatic cinema endgame to such a tech takeover: each track sounds something out of a dystopian world overrun by sentient technology, rustling with life no man could have ever foreseen. In terms of music, withal, it’s as close to organic as any contemporary project has gotten before or since – because from the moment the needle drops, structure is obsolete. VDC cleaves over an hour of content into chunky slabs of nearly ten minutes each, the slabs themselves encasing watery tunes that seem to flow like consecutive cataracts into whatever follows. Crucial to the organic element, all songs except one (dsco) neglect to adopt the oft-repeated verse-bridge-chorus structure – tracks often open with rustling electronics and close out with forceful mantras, seldom utilizing human vocals in-between unless they are to accent what scenery is already occurring. The music is in charge, and the human is just another instrument.

Yet beyond the conflict of digitized sound, a separate dynamic makes its presence felt throughout the record without explicit announcement: creativity versus the mainstream. It’s a chasmal rift that has shaped artistic direction for decades, birthing careers lived in the spotlight and keeping just as many starved on the outskirts. The dynamic is one that often goes without saying. It exists as a Bermuda Triangle raging on in the ocean of music; steer clear of it and all is well, dare to sail too close – get too creative – and widespread dismissal is the boulder that drags you underwater. Velocity: Design: Comfort is living proof that, though not broadcasted, this dynamic is alive and breathing.

Honesty comes naturally, take it or leave it.

-Roberto Burgos

Valerie Cooper and Roberto Burgos sit together on a sofa, both pairs of eyes briefly wandering about the room after commercial success is brought up in conversation. Behind them, a teal sheet is draped over a set of blinds to block out the afternoon sunlight.

“I always wished people would appreciate it more,” Valerie says of VDC. “We did shows and there was hardly anyone there.”

Roberto nods in agreement. “This is who we are,” he declares, speaking on the duo’s sound soon after. “We stuck to our guns. Honesty comes naturally, take it or leave it. But at the same time, I always wondered: ‘why can’t we have just ten more people at our shows?’”

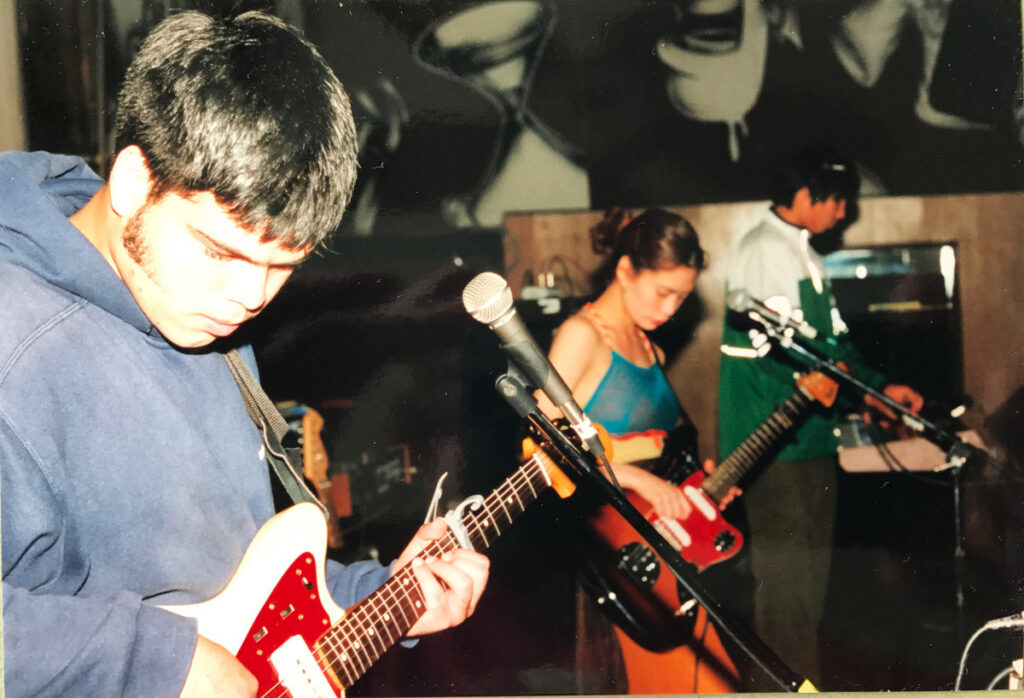

There are various indicators the two mention of how creating for creation’s sake was VDC’s motive. For one, the album was recorded (in a bedroom) over an extensive period that, compiled together, roughly adds up to nine months. All vocals were taped from behind the locked door of either a closet or a bathroom. And on a tertiary level, when I ask what made the lengthy construction process enjoyable, the first thing they do is turn to each other.

But on the other hand, between the lines, one of many comprehensive signs pointing towards foundational creativity is how much sheer complexity they were willing to navigate to produce the sounds they did.

“If I remember correctly, I had a laptop, external recording gear, some old-school samplers at the time – this was the late nineties – we still had all the old analog, digital gear and stuff like that,” Roberto recalls. In a photo Valerie sends me after our interview, the complete equipment layout for VDC is scribbled onto a piece of looseleaf covered from top to bottom with blue ink: written lines include “Yamaha YME8 Midi Expander (like a thru-box)”, “Waldorf mini-WORKS-4 pole analog filter ($400)”, and “ALESIS (We have 4 of ‘em ^ q2’s).”

For all of this, reception equated to far less than what was hoped for. While the pair saw many of their label mates garner mass attention and accolades for what they put out, mere write-ups for Velocity: Design: Comfort were few and far between. On top of that, upon being shown the record, Valerie’s father gave Cooper and Burgos separate lectures about how much better he felt they could do on it: “why don’t you make songs like the Beatles!?”.

The structural genotype Cooper’s father refers to encompasses the complete umbrella of popular music. In the day of its namesake, this was defined by an emerging nationwide rock n’ roll scene emanating from guitars toted by Chuck Berry and George Harrison. In present day, the spotlight is dominated by genres like hip-hop and pop, many of which spent previous decades forging individual cultures that followed – and still do follow – closely in the direction of the art itself. According to Statista, in 2018, hip-hop, pop, and rock combined for nearly 56 percent of the total share of album consumption in the United States, the next three most popular genres after those being R&B, Latin, and Country (28 percent combined); Of the less popular class, the highest percent total earned was 3.7 – Electronic Dance Music.

Thus, it’s easy to make songs like the Beatles. It’s fairly straightforward to shape one’s work of art into a common mold that guarantees some sort of mainstream appreciation, or if not that at least, money in the pocket.

But for those who dare to get too creative, the question posed by Valerie’s father persists: “Why don’t you make songs like the Beatles?”

“We don’t want to do what everyone’s doing,” Valerie tells me. “We want to do something that we feel.”

Velocity: Design: Comfort’s album artwork embodies the self-created universe it thrives in. In the foreground, there is a haphazardly jumbled-up architectural project that screams the essence of a post-apocalyptic Manhattan. It sits afloat in midair, stuck amidst the three-dimensional x-and-y-axes of (respectively) a blue-line grid system drawn over white (x) and a wall coated in over seventy straight lines of color. In the background, there are cumulus clouds. Excluding the abstract building, all elements extend infinitely, until, at some microscopic dot near center, indigo heavens, gridded lines, and rainbows intersect.

It’s exactly what the music feels like: some tiny, infinite, microscopic dot at the center of nothing in particular. It comes without context, without warning, without thought – there is no line to be drawn back to what you once knew, nor what you once saw possible.

But somehow, in the right world it makes perfect sense. And – though it may come with a hefty price tag – for those who arrive there, it’s a sense worth making.