This Heat: Abstract Wonderers Ripping the Curtain Away

In light of the digitization of This Heat’s discography, we take a look back at the band that frightened, innovated, and tantalized the masses from a meat refrigerator.

SAMUEL HYLAND

Over the course of several tone-setting days that followed the British prog rock band This Heat’s 1977 John Peel session – a 42-minute exhibition of warped strings, ghoul-esque howls, and focused paranoia going from nightmarishly somber to nightmarishly ear-splitting in intervals as short as mere seconds – Peel found himself inundated with listener requests for “more music like This Heat.” He rejected such petitions each time they surfaced – the constant rationale cited being simply that “nobody else sounds like them.”

With the long-awaited 2020 digitalization of their complete discography, such rhetoric has been proven to transcend the boundaries of age. In what brief years spanned the aforementioned John Peel session (which kickstarted their short time in the limelight) and the breakup that closely trailed 1981’s cult classic Deceit, their final studio album, This Heat’s music embodied a sense of impending doom simultaneously omnipresent and inescapable to the natural ear. The trio channeled unconventional musical juxtapositions to breed tension: acute technology turned guitars into squawking androids from the apocalypse; a mix of pitch-shifting harmonizers and intermittent bass notes translated audible doomsdays into semi-palatable funk jams on tracks like 24 Track Loop; lo-fi soundscapes engineered convoluted backdrops for whatever action paintings would come to life via instrumentation. But, perhaps even more often, their songs did not make any sense. The first thirty seconds of their John Peel session (like a vast majority of their stuff) is a swirl of leftfield speaker feedback. Shortly afterward, there’s a laserlike locomotive bass guitar reminiscent of Krist Novoselic’s Scentless Apprentice riff; it radiates underneath a relentlessly dissonant electric guitar that doesn’t seem to have an off button. Three minutes later, the song is reduced to a shamelessly improvisational string solo. Then, eight minutes in, the whole thing is an organ-infested madhouse that mockingly inquires of you – the terrified visitor – how much can you take? About two decades past their heyday, the band remains solely occupant of a single category yet to take definition. And just the same way, about two decades past their heyday, no one is either able nor willing to emulate such a dynamic construct.

This Heat emerged, lead man Charles Hayward told the Guardian this past September, from similar circumstances to the era their work finds itself reemerging amidst: the end of the world. Whereas as of now that looks like the international outbreak of a deadly plague, in the peak of Hayward’s artistry, it was the constant threat of nuclear warfare and-slash-or deadly global conflict. “Thatcher and Reagan and the concept of mutually assured destruction,” Hayward cited, describing what circumstances brought his paranoia into focus.

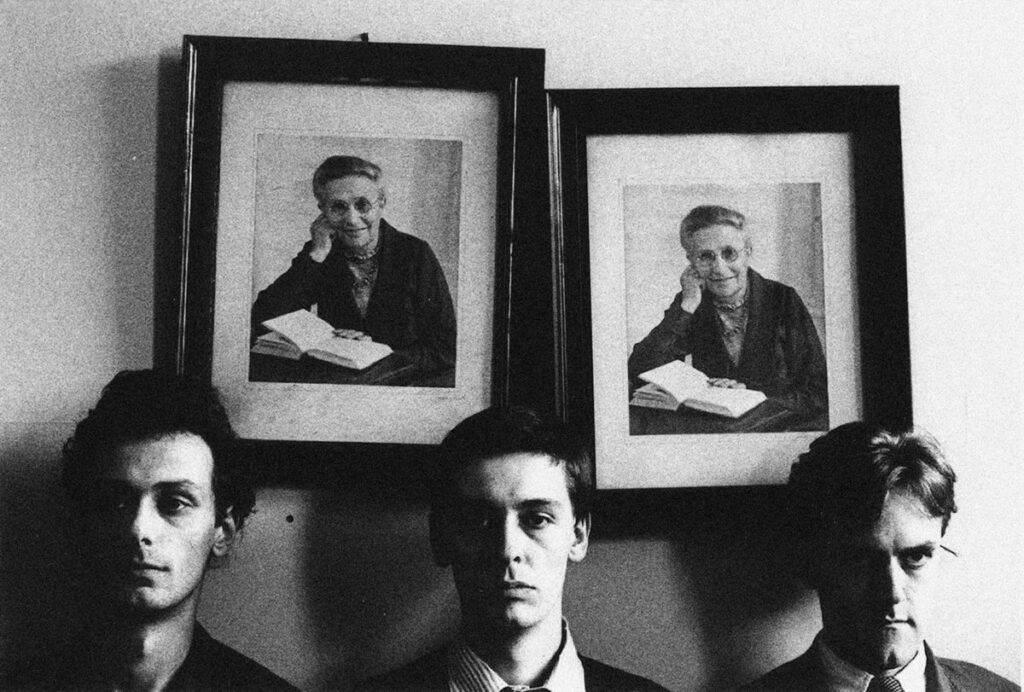

As these issues were heating up, and after Hayward left his previous musical act Quiet Sun, he posted an ad in Melody Maker. The advertisement allowed for Charles Bullen, a fellow London multi-instrumentalist (guitar, clarinet, viola, vocals, tapes), to join forces with Hayward, soon to be accompanied by the late Gareth Williams. The arrival of Williams completed the trio in two ways: yes, of course, he was the namely third member that made them a trio in the first place, but the outstanding element of his membership was that he was not a musician. And somehow, his illiteracy in terms of music made that (the literacy) of the entire group just as much more bona fide. “Just the openness,” Bullen recounted to the Guardian. “Charles and I has a certain level of what you’d call chops, whereas Gareth didn’t have those chops as such, so he was more involved with texture and timbre.”

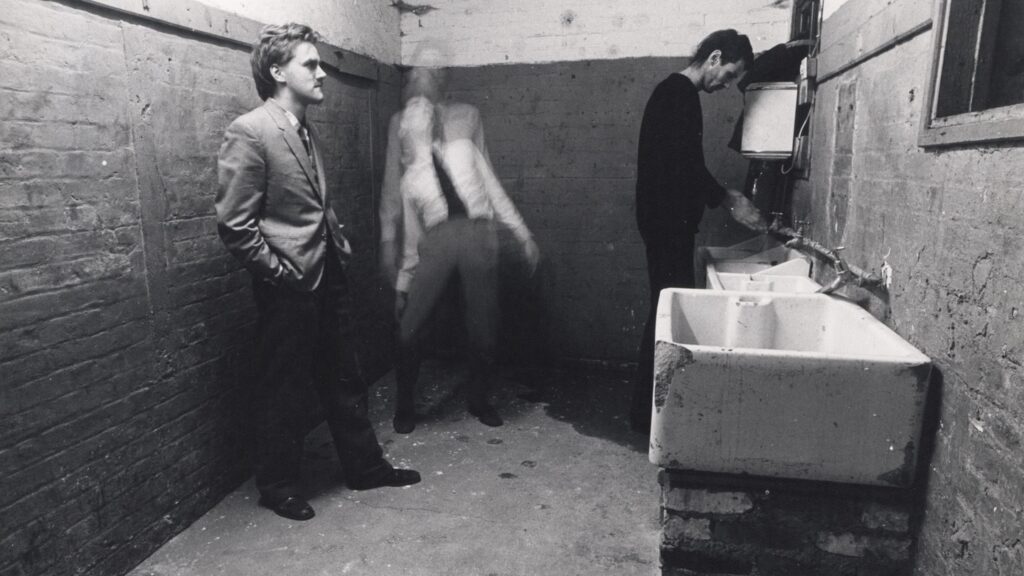

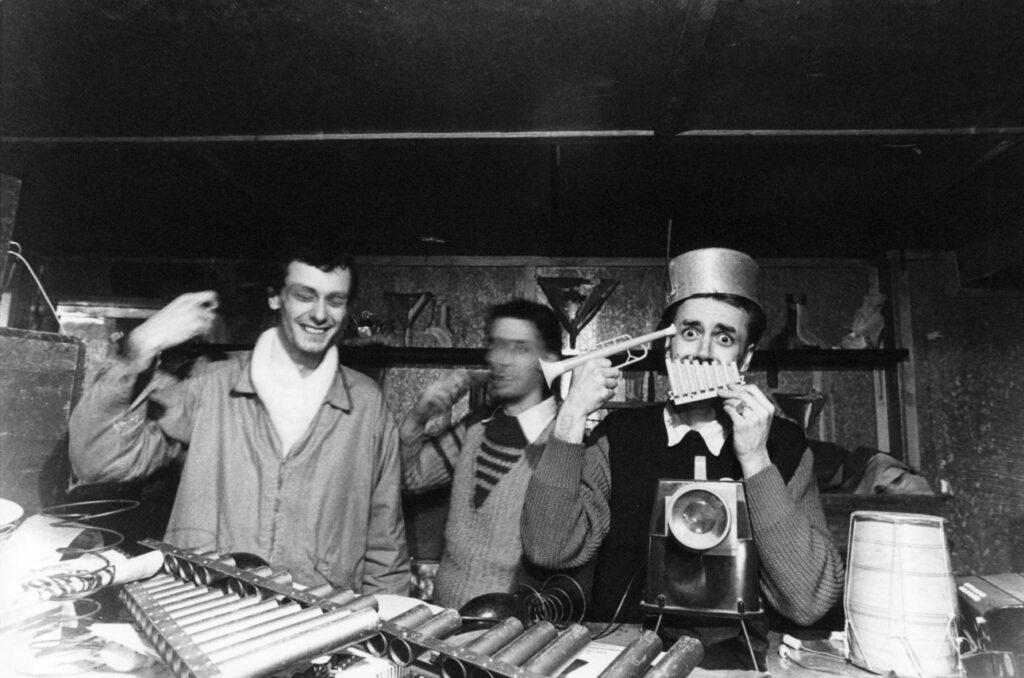

Such synergy displayed by the group on paper was only multiplied by hours spent in their unorthodox rehearsal space. This Heat practiced in a refrigerator. “It was a huge fridge in a disused meat pie factory – none of the electrics were working, but there were these metal walls. It had no daylight. We opened the door and there was a sort of micro-atmosphere in there, it was like you suddenly went into the tundra,” Hayward said. “There was a bit of mist floating around, there was blood-encrusted dust along all the corners and everything. It took us two weeks to clean the place up. It was chaos, but the sound of the bass drum in there was incredible.”

His closing point – but the sound of the bass drum in there was incredible – epitomizes the matter-of-fact collective attitude with which the band approached recording music. Their eponymous debut album, affectionately referred to as ‘Blue and Yellow’ on account of its cover art, was recorded between the years 1976 and 1978 – and although for as much time as it took to make, the record may register as careless, a less contemporary lens magnifies what backbone such a release required.

The record opens with Testcard (Blue), an eerily punctual forty-five second number of periodic beeping noises. Not Waving, the third track on the album, drawls out just around eight minutes of slow-burning dread, fading in with the disorienting, intermittent electrical haze left over from Testcard, graduating onto a somber horn section that haunts the ear, then featuring some of the only vocals in all the LP’s 45 minutes:

“Yes, I will go up there

Up there where I know you cannot find me

I held on to the steel rail too long now

I know I must let go

Here I am in the ocean

Not waving but drowning

Just a nervous reaction, please don’t rescue me

So cold I can’t feel my toes

Oh, let them go, who needs them?

Circulation stand-still

H2O can freeze you to the marrow

Learn to love the water

It will love you like there’s no tomorrow

There is no tomorrow.”

It is a harrowing ballad that, much like the band itself, delves into the concept of not being ready to face cruel anxieties linked to the real world. In a testament to the timeless vain dwelled in by its composers, Not Waving’s delivery – Hayward’s vocals, to be specific – eerily redirects one to the empty bellows of Ian Curtis and Joy Division, or the forlorn cries of Thom Yorke and Radiohead in formative years prior to breakout releases. Although their music has existed in a tier of its own, the entities, each one prophesying its own TEOTWAWKI, behind it have not. Such doom is undeniably tangible: In Diet of Worms, the perpetual electronic screech may as well be a blood-curdling scream; In The Fall of Saigon, the single-string line that emerges from the late-track wreckage is no different from a futile ambulance siren growing louder as it advances through fatal ruins; in the seconds that conclude Water, a congregation of manipulated guitar effects sounds like a flock of neglected, dying, thirsty chickens gobbling desperately aloud for just that.

Yet no matter how careless or unorthodox This Heat sounded, they happened to emerge in the optimal musical and societal settings alike for them to be just where the English public was naturally drawn. The way Bullen put it, “There’s a quote about This Heat being pre and post everything, which I liked. There wasn’t a scene that we were part of that could then be defined to that particular era.” Societally speaking, the trio broke ground at a point where there was mass disillusionment brewing with every day that passed – on top of a Cold War that threatened to drag the entire world to hell with the United States and the Soviet Union, tensions preserved from World War II left deep chasms in the push for global peace exposed, threatening to break the entire planet wide open one more time at any given instant. Musically, the disillusionment was more subtle: it wasn’t that Londoners were tired of punk rock; the genre was dying a slow death. When John Lydon of the Sex Pistols left his original band out of frustrations with since-disgraced manager Malcolm McLaren, founding Public Image Ltd. and reclaiming his identity in the process, it was not only a personal rebranding — unofficially, post-punk arose from the carcass the Sex Pistols left behind, splitting the genre down the middle between past and future and leaving startups like This Heat to make sense of the debris.

And still, somehow, the group managed to precede the new wave (the John Peel session came out a year before Public Image Ltd. was founded). Their arrival onto the scene came at the acute single perfect moment in time between the punk rock candle beginning to burn out – the point at which longtime listeners naturally began seeking after new variations – and the flame fully dying, post-punk’s pioneering class soon becoming nearly just as overpopulated as that of its predecessor.

Many needed to hear an audible response to the turmoil they found themselves surrounded with. Whatever solace was not provided by government was discovered in music and its many scenes; disgruntlement was contagious, and more often than not, hearing it represented in sound validated such feelings for the typical listener. It is the exact dynamic that made it possible for a band to play complete nonsense to the contemporary ear on radio, then go on to leave John Peel inundated with phone calls begging for “more music like This Heat.”

One can easily compare Hayward, Bullen, and Williams’ efforts to King Crimson, the revered group that crystallized England’s growing progressive rock movement with the release of their debut full-length album In the Court of the Crimson King. At great length, a main reason for which In the Court of the Crimson King achieved the legendary status it enjoys today is that it gave progressive rock a dual definition long-void: the genre was musically characterized by consistent progression, in the way that makes ten-minute tracks with about four different distinct parts make sense – but on the flip side of it, progressive rock was now just as progressive in its messaging. Whether done explicitly or between the lines, prog now told stories of dystopian futures via audible carnage, predicting horrific ends to the many instabilities present in the modern world. “The tortured lyrics of Greg Lake, at odds with the world, are in stark contrast to the free-loving optimism of their contemporary hippie ideologies and thus King Crimson railed against the norms of the time,” music writer Luke Saunders wrote of the LP on its anniversary this year. “The dark apocalyptic messages of 21st Century Schizoid Man, Epitaph and In The Court Of The Crimson King, shed the optimistic hippy ideologies of the ’60s and stared reality straight in the face.” The powerful, surrealist imagery, much like that conjured by This Heat’s work, is said to be inspired by the Vietnam War and the impending anxiety of nuclear destruction. On songs like the somber ballad I Talk to the Wind, doubts in spirituality and the presence of a higher power germinated from helplessness made omnipresent by global bloodshed. “I talk to the wind; My words are all carried away,” laments frontman Greg Lake. “The wind does not hear; the wind cannot hear.” Heavier cuts like the aforementioned 21st Century Schizoid Man (often regarded as the first ever heavy metal song) threw the gore in one’s face, packing inhumane lyricism in with battlefield-esque musical terrains that teleported consumers into the hades of tomorrow.

Through such soundscapes, both King Crimson and This Heat raise a question mark around the concept of abstract music. Is any of it meant to be palatable? In the world of physical art, abstract works created during the movement’s initial surge served to push conceived limits to what art was at all. Much of it, too, was not intended to carry any meaning. Duchamp’s Fountain and Kandinsky’s Composition 8 were poorly received by high art gurus who had spent their lives catering to realism. But the underlying intention of each piece, with the hundreds that came alongside them in their respective era, was to highlight a fault in common knowledge: in this case, a foundational elitism in art’s surrounding culture that held value exclusively to the criterion of detail and effort. Even if art pieces sacrificed being broadly palatable to prove otherwise (Duchamp famously faced excessive pushback for his attempts to submit the Fountain sculpture to various galleries), the ultimate outcome of each piece was a re-thinking of what constituted creative work itself — and as of now, 20th Century Abstract Expressionism is widely regarded as what shifted ideas of art from a material process to an intellectual one.

Although King Crimson and This Heat criticized society more than they did the music business, traces of abstract expressionist backbone were still at the root of their output. The 1960s and 70s were a time period in which contemporary pop music found epiphany-like rejuvenation; up from monochrome decades past, during which culture was limited to variations of jazz-rooted choreography, the hippie era birthed an shockwave of new drugs, creativity, and informality strong enough to mushroom even, if not especially, into what characterizes the present cultural climate. In the same setting as acts like Pink Floyd and the Beatles, both bands took on a challenge of bearing grim warnings and – rather than hiding them beneath jivey melodies – making the instruments just as dreadful to the ear as the words were.

In recording their final studio album Deceit, This Heat approached this dynamic differently than they did with any other record. “We had one three-month period where rehearsing involved us sitting on chairs, not actually playing, just talking – the melodic thing on Deceit came out of that,” Hayward told the Guardian. “We wanted to address the audience in a slightly different way now.”

While Deceit is more melodic and approachable than any other This Heat release, it is as far anxious and disturbing as the group has ever roamed. In the opening track Sleep, whereas previous LPs boasted repetition in speaker hum and miscellaneous electronics, the continuous element is – over the ghastly bottom layer of rhythm-based flute concoctions – a repeated suggestion to “sleep sleep sleep, go to sleep.” Hayward’s hum registers as a malicious lullaby, illustrating the monster of consumerism as it rocks us to rest with material properties, quickly switching off our collective intellect as we bask in the unconscious. Paper Hats, their most popular track in the United States, is the only song of This Heat’s written by Gareth Williams. In a chilling mirror image of what social turmoil ravaged the U.K then, the lyrics, some melodically recited and others hollered, are all questions: Well, what do we expect? Paper hats? Or maybe even roses? The sounds of explosions? The final verse before a minutes-long closing musical break is sung with the villainous croon of a dictative adversary. Williams’ questions seem more sarcastic than inquisitive, mocking the helpless state of whoever may be on the other end: What does this tune signify? What is its meaning? Is it really that straightforward? Or are our ears beyond words?

Yet, of nearly an hour’s worth of similarly chilling musical interrogation, Deceit’s most grim selection is a number titled Independence buried deep down at the album’s ninth track. Over chaotic flute assemblies in the backdrop, and an unnervingly irregular drum pattern, Hayward recites the opening statement of the Declaration of Independence. The vocal tune, in contrast, is derived intentionally from The Fall of Saigon, off of their debut record. The track is forthright in its irony. The recital of Thomas Jefferson’s words is not done in respect; it’s done in spite — yes, all men are created equal, but inequality sat at the root of what teetered the human race between continued life, and self-extinction via mutually assured destruction. All one can do is recite the words. All the words can be, is empty. The reality, like a trance, is drilled into one’s ears until it reverberates within the skull, until one realizes that they will someday die.

At their musical peak, this is exactly what This Heat specialized in: they ripped the curtains away from hope, repetition, and routine alike, revealing the monstrous, protuberant ogre that lived beneath. Every time, it was pointing at its observers with a snicker – and every time, the ogre was humanity itself.

“I always wanted to address the straightest guy in the room,” Hayward said of his intentions with the band, concluding the Guardian interview from September. “I wanted to find ordinary people, it wasn’t for some weird squat anarcho-punk leftfield thing. People who … define music by the fact that only a few people get it. I sort of hate that attitude, really. The notion of the cutting edge, I find this absolutely arrogant. I think everybody’s on the cutting edge. I think the old lady knitting a pair of socks for her granddaughter is at the cutting edge as much as somebody doing a tribute to Pina Bausch or something, because we’re all in this moment, this moment is now. No one is ahead of anything else in this nowness.”

Unfortunately, the present nowness for This Heat only lasted from 1977 to 1981. Soon after the release of Deceit, Gareth Williams parted ways with Hayward and Charles – the group made an attempt to continue onward with replacement members, but not before long, they ultimately called it quits. After a reunion tour was scheduled for 2001, following just a few rehearsals, an already-ailing Williams succumbed to cancer, effectively ending all iterations of This Heat.

The recent digitalization of their discography serves as an intimate time capsule to a band that tried to change everything. Encased within it, there are brash warnings, prophecies of the apocalypse, spirits from the past, and fears you have yet to discover.

Also within it, though – maybe not in sound – are all of the moments that defined their rise to cult stature between formative years. On one of these nights, the group played a gig at the Chelsea School of Art in London. By the end of the show, their audience had grown so divided that an all-out brawl was barely stopped from breaking out.

Reflecting on the commercial potential such reactions suggested, Bullen remarked: “I think they thought that we could possibly be a new Pink Floyd or something. I mean, that obviously didn’t happen, musically or sociologically or politically.”

One is forced to wonder if This Heat’s surviving members bear any pain in their hearts for commercial success missed out on. One cannot ask John Peel for “more music like This Heat” because nobody else sounds like them. But for as much good as it did the scene it fostered, the knowledge that we may have never encountered it without its resurfacing is perhaps the only thing more horrifying than the future they envisioned: the warning may have never reached us in time.

You can stream This Heat’s recently digitized collection here.