A History of Villainy Versus Anti-Heroism in Hip-Hop, & Where Slowthai Fits In it All

How Slowthai makes the most of a make-or-break point in his career, and how others have fallen off of the same cliff.

SAMUEL HYLAND

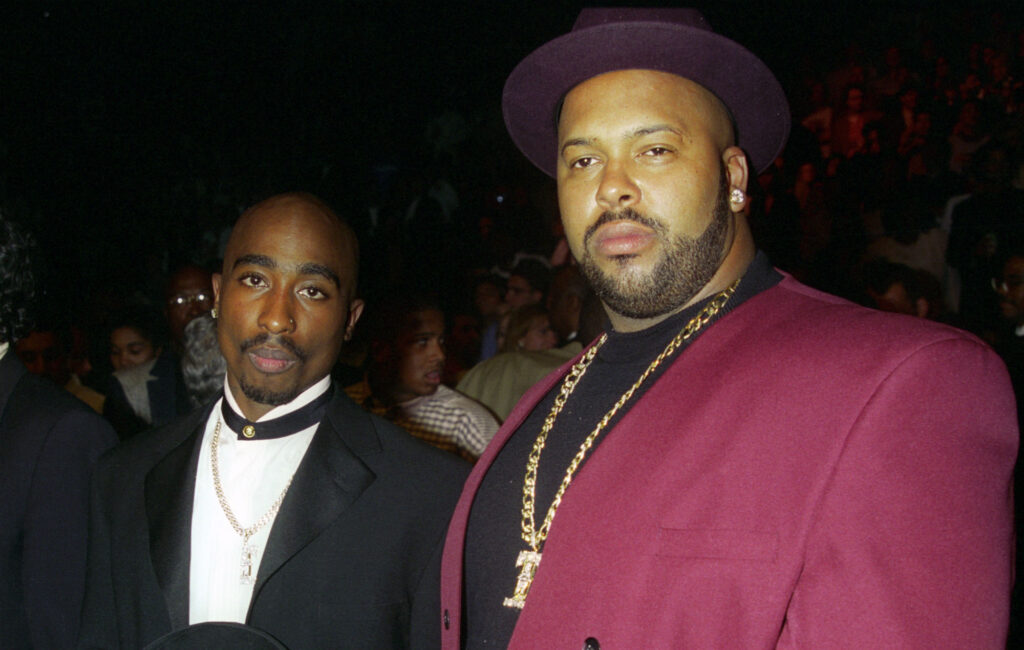

When the prolific hip-hop journalist Touré visited Suge Knight at Tarzana’s Death Row Studios in 1994, his sole intention was to document legal issues between Knight and his longtime mentor Dick Griffey for XXL. By the time he left, he had barely escaped death.

Up to its turning point, the pair’s formal interview went considerably smoothly. In the XXL article that followed it, even, Touré recounted that Knight “was articulate and funny and put me at ease” – they sat face-to-face on two blood-red loveseats, conversing lightly about olden days between Knight and Griffey, beating around the bush when it came to more pressing matters of looming legal troubles. All pleasant auras quickly departed, however, when Touré worked up the courage to ask about the primary subject of the piece: Knight’s impending lawsuit.

“Man . . . a nigga wan come up in here talkin bout lawsuits . . .” Knight remarked, immediately shifting his tone from witty to disdainful.

When Touré rose with his tape recorder, Knight asked him where he was going. And – when Touré expressed that he planned to leave – he told him that he was staying right there. Knight summoned a livid, muscled, “street soldier” into the room, allowing him to lunge at Touré for a brief moment before holding him back. After the two seemed to go off into a corner to decide Touré’s fate, Knight lifted the journalist by his shoulder, digging his fingers into his flesh en route to press him against a piranha tank located in a nearby office.

“If you ever fuck with me . . .” he started.

“Yes, yes sir . . .”

“If you ever come up in here askin bout some lawsuit-”

“Yes, no, sir . . .”

“. . . Rewind the tape.”

Knight grumbled, motioning Touré back to the facing blood-red loveseats from whence they came, “You done burnt your bridge with Death Row. Someday you gone need us, to do a innaview or summin. But you done burnt your bridge.” Then, he told Touré to restart his tape recorder. He proceeded to recount an hour’s worth of interview material back onto the record based on pure memory, before kicking the still-trembling reporter out for good.

The oft-retold anecdote epitomizes a lasting anti-heroic legacy Suge Knight cemented prior to his lengthy prison sentence. For his entire career, he forged Death Row Records with the kind of brash, one-dimensional, villainous mirage that gave hip-hop diplomacy a permanently negative connotation: whilst boasting a far more extensive list of criminal felonies, he was known to have made enemies strip at gunpoint as an intimidation gimmick; he gave terrified employees the options of either drinking their own urine or being assaulted by him before he fired them; and – notwithstanding most allegations are baseless – he is infamously rumored to have played a considerable role in Tupac Shakur’s killing.

Although Knight is not the first rap-adjacent figure to don a nefarious front, his controversial career embodies a tightrope similarly characterized MCs have walked both before and after his heyday. When contemporary hip-hop emerged onto the inner-city streets of both New York and Los Angeles, there were two still-standing connotations surrounding the genre: one villainous, and the other anti-heroistic. For consumers in rural America, the conventional gangster rapper was regarded as a gangster before he was regarded as a rapper, thus making it far easier to condemn any resulting art for its violence rather than appreciate it for its content. For listeners hailing from the same worlds as conventional gangster rappers, those MCs were viewed not only as artists, but as never-before-seen real-time prophets who somehow put unspoken truths into poetry that doubled as good music. There was little possibility for a square “hero” persona to thrive in the genre. You were either a villain – the domestic threat suburban America was quick to label most hood-emerging acts as – or an anti-hero: the community staple whose honest raps outweighed any malevolent tidings carried on outside of music.

Conventionally speaking, the ideal standing for any MC was to exist in both spheres at the same time. But whereas the absolute most positive reputational outcome was virtually impossible to attain (being a hero to both one’s own community and the rest of the country), the double-negative of villainistic standing within all consumer circles bore its own rare class of infamy.

In the case of Suge Knight, at least for the first part of his career, the distinction between the anti-hero he remained and the villain he would soon become existed in how he was regarded by those surrounding him. In the aforementioned Touré article, a source familiar with Knight’s criminal history went on the record as saying: “Suge to me is a real gangster. He has a very heavy violent side and if I were giving any advice, just don’t cross him and expect to get away with it easily. He’s a very dangerous guy.”

“But unlike mere gangs, where betrayal resulted in one either being strategically murdered or otherwise ousted, the hip-hop community still required one to be a rapper whether he forsook his benefactors or not.”

For a while, Knight lived comfortably in the realm of being merely regarded as dangerous, all the while still contributing to the West Coast rap scene significantly enough to attain anti-hero stature. Yet, once his credibility dwindled, his anti-heroism followed suit. After founding Death Row Records alongside Dr. Dre in 1992, a reputation-defining series of misdemeanors included but were not limited to: pistol-whipping two aspiring rappers for using the wrong phone in his studio, derailing Eazy E’s solo career in his last few years alive, and being in and out of prison every few months for repeated parole violations. By the time Tupac was murdered, Suge had long transitioned from West Coast protagonist to nationwide menace, and now, to worldwide outcast – a position he still holds today. No matter how much he did for inner-city California, it was his own internal evil that pushed his prominence down to unrecoverable depths.

“I trust you,” Knight told the judge overseeing his 2015 hit-and-run murder case. “You’ve been my judge and my advisor . . . You’re my only friend now.”

After decades of crafting a reign of terror predicated upon dual domination over both the streets and the studio – loyalty to each being an absolute precedent – he has reached a point where his only ally is the universal symbol of the American legal system.

Sitting among very few unchanging elements of hip-hop over time is the metric by which one becomes a villain within his own community. A great deal of rap music’s surrounding culture is either based on, or influenced by, gang-related subject matter – when hip-hop skyrocketed from ghetto subcommunity to influential lifestyle in the 80s and 90s, acts like N.W.A, Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre quickly rose in the ranks because of the criminal realities they commercialized. Both the East and West Coast’s rap scenes were widely interconnected by gang links that spanned statewide, soon making adjacent music more an extension of criminal lifestyles than a reflection of it. But unlike mere gangs, where betrayal resulted in one either being strategically murdered or otherwise ousted, the hip-hop community still required one to be a rapper whether he forsook his benefactors or not. Rural America saw a thug. Urban America saw a traitor. There was no way to disappear from the public eye, nor was there any means to shed the double-negative of villainous notoriety on both sides of the tightrope.

One month after Suge Knight was handed the 28-year prison sentence he is currently serving, the charismatic New York rapper Daniel Hernandez, known interchangeably as Tekashi69 and 6ix9ine, was apprehended by law enforcement as part of an ongoing investigation into his native Nine Trey Bloods gang.

The defense – eleven Nine Trey gangsters in total, including Hernandez – went on trial for charges related to racketeering, weapon possession, and conspiracy to commit murder. Initially, Hernandez pleaded guilty and was denied bail. Then, on February 1, 2019, he entered a pivotal deal with law enforcement that saw him reverse his plea to guilty, admit his own guilt in the allegations faced by Nine Trey, and infamously testify against his fellow gang members in court.

After his sentence was reduced to two years, with only thirteen of those twenty-four months being served behind bars, inner-city New York streets he once ruled reviled his very image; the thuggish, raw exterior he had worked his entire career to cultivate evaporated in the wake of an irreversible newfound legacy as a “snitch.” And perhaps more pressingly, his life was in grave danger: on top of his having received death threats even before he opted to cooperate with authorities, wire-tapped members of his former gang were recorded plotting to “super violate” him for his breach of street code, a sentiment keenly perceived by the rapper’s lawyer as an attempt to murder Hernandez. Not covered are the truckloads of grim warnings he received from fellow rappers and curious observers alike both over social media and in letter form.

But even prior to his current legal troubles, he had garnered himself quite the negative reputation amongst inner-city peers for his own moral transgressions. In 2015, after pleading guilty to the use of a child in a sexual performance posted widely online, he was sued for child sexual assault, child sexual abuse, and infliction of emotional distress. Then, in a later interview with Fox 5 New York, he admitted to pummeling his ex-girlfriend after having found out that she cheated on him with another member of the Nine Trey Bloods gang. Proving crucial to his later investigation, he was one of many plotters behind the attempted murder of Chief Keef outside the W Hotel in Times Square in June of 2018.

“How would you feel if I go out there on the ledge and jump off that building and kill myself? That’s what society wants me to do.”

In his first interview since being released from prison in 2020, he told the New York Times pop music reporter Joe Coscarelli, upon being asked whether he had regrets about the entire matter: “When I was kidnapped, was I a victim? Did I cooperate? No. When they were stealing money from shows, did I cooperate? No. Did I have many chances to tell the police what I saw? Yes.”

The leading defense used by Hernandez to vindicate himself of widespread scorn was that the Nine Trey Bloods gang had never been loyal to him in the first place. Internal power dynamics within the group spilled over into the public view in July of 2018, when the rapper was forcibly kidnapped, beaten and robbed for his belongings by fellow gang members Anthony “Harv” Ellison and Ellison’s associate only known as “Sha.”

“I was following a street code that was upheld by me and that I thought was real. Before I broke the street code, how many times was it broken to me? ‘It’s all about honor, loyalty.’ Well, let’s talk about if sleeping with somebody’s girl is honor, kidnapping somebody is honor, stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars from them is honor, trying to kill them is honor. ‘Snitching’s not street!’ But street is taking advantage of one of your homies?”

Though many followers conservative of old street values may not have agreed with his standpoint, 6ix9ine somehow miraculously remained afoot on the tightrope, managing his still-growing music career from various secret witness protection locations across the United States, recording music videos from confidential, windowless, high-security green screen rooms whilst solely accompanied by whoever happened to be featured on the songs in question, and maintaining his status as a social media troll behind millions of followers, equally igniting new rivalries and pouring fuel into old ones. His latest album TattleTales (2020) boasted features from Nicki Minaj, Akon, and Lil AK. Its lead single “Gooba” has amassed 300 million streams on Spotify.

“How would you feel if I go out there on the ledge and jump off that building and kill myself?” Hernandez asked Coscarelli at one point in their New York Times interview. “That’s what society wants me to do. (. . .) I’m already at the top, now (I have to) keep making music and keep dominating.”

“But you’ve got to evolve. What’s next?”

“Just keep dominating.”

To be a rapper and lose support from all bases is the equivalent of being an NBA player hated both at home and on the road: every accolade comes with an asterisk, because everyone despises you too much to give you credit for what you accomplish. Cultivating both the home and away crowds, on the other hand, is the near-impossible realm in hip-hop – basketball included, to be fair – wherein the long-mystical pinnacle has been reached, and there is no place to venture but down.

“What you see when you talk to me is what happens when you get rich. What happened to Pop is what happens when you die trying.”

The concept is one heavily addressed in the controversial gangster rapper 50 Cent’s debut album Get Rich or Die Tryin’. To ‘get rich’ was to rise perpetually through the business of rap, mastering both the music and its surrounding culture en route to “making it out” and spending life’s remainder consuming all benefits garnered along the way. To ‘die tryin’ was, well, to die trying. If one was not fortunate enough to have the level of legal luxury afforded to 6ix9ine within the past few years – which many were not – any promising ascent to the ceiling was pierced by bullets of either the jealous, the betrayed, or the rivaled.

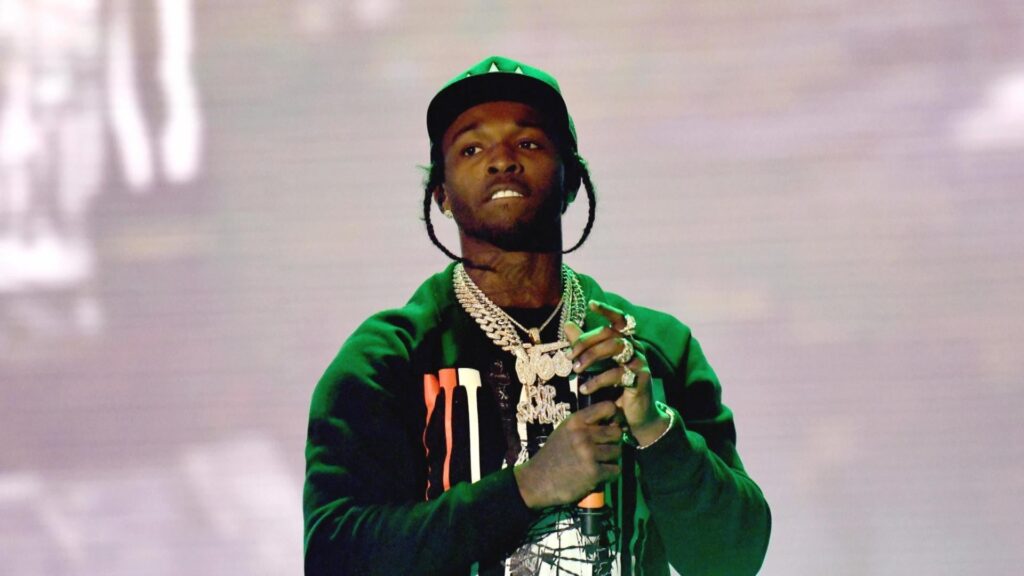

The New York-centric drill rapper Pop Smoke, born Bashar Jackson, rose to prominence on the same urban streets as 50 Cent nearly two decades after his breakout. Jackson mirrored 50 Cent in many ways: he touted uncannily similar rhyme schemes with the same menacing, gravelly inflection; he emerged from a background defined by extensive gang infrastructures, parts of which he partook in; and, in gradually becoming the new spokesperson for a lifestyle brushed over by the rest of America, he was fastly trekking a notoriously unforgiving course along the way to one thing – getting rich.

When the New York Times pop music critic Jon Caramanica conducted interviews with over a dozen of Pop Smoke’s closest friends, colleagues, and collaborators this past June, 50 Cent reflected on mentoring Jackson one-on-one for the first time.

“The experience was a little weird. Because when I first started talking to him in the office, I was watching and he would look down at his telephone. He was typing at the same time. And there was a point where I’m like, is he listening?” he recalled.

“I got up so I can kind of see what he was doing, and when I got to the other side of the table, he wasn’t not paying attention to me, he was just writing what I said down. Dead serious.”

Much like 50 Cent, Pop Smoke had also played his cards to a tee when it came to grabbing the reins of international intrigue. Having added a distinctive New York element to the drill subgenre that thrived for years in London’s hip-hop underground, he fostered correspondences with revered UK acts like Skepta whilst at the same time diligently heightening relevance in his own hometown. Before his first full-length album was even released, the Off-White founder Virgil Abloh invited him to attend several of his shows at Paris Fashion Week. By early 2020, he had cultivated a worldwide network of supporters that loved him just as much for his persona as they did for his music.

On February 19, however, he was shot and killed by multiple gunmen in an armed invasion of his temporary Hollywood living arrangement.

“What you see when you talk to me is what happens when you get rich,” 50 Cent told Caramanica. “What happened to Pop is what happens when you die trying.”

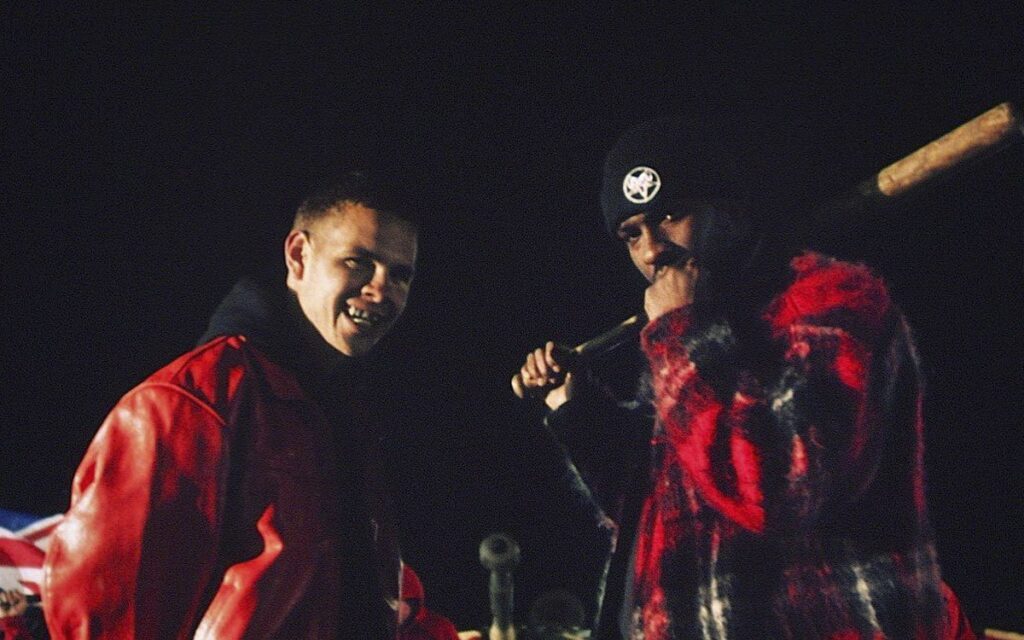

Although he may be easily overlooked amidst a growing class of American rappers advancing towards their ceilings at far faster rates than their predecessors, if there is anyone winning at the same dangerous game Pop Smoke and 50 Cent played – with no sign of any abrupt end as of yet – it is Tyron Frampton, the drama-attracting UK rapper who performs under the name Slowthai. At just 24 years old, Frampton has amassed an international legion of loyal followers who come for his mischievous antics and stay for his high-energy act.

His well-received debut album, Nothing Great About Britain, was released two years ago in 2019. Clocking in at just under an hour, it embodies wholly the anti-hero classification he has perfectly, albeit unintentionally, molded himself into over time. In the opening track, he both calls Queen Elizabeth II a “cunt” and tells Kate Middleton directly that he would wife her up. The raucous ensuing track “Doorman” sees him quip about getting carried out of the club for slapping Prince Harry. On “North Nights,” he unapologetically insinuates that former Prime Minister Theresa May aspires to be the English business magnate Richard Branson.

Yet, feasibly most significant of his rapid ascent towards getting rich is the third track on Nothing Great About Britain, “Inglorious.” The song presents itself as an audible sneer, boasting a shrewd lyrical exchange between Frampton and Skepta. In a video with Genius, Frampton detailed how he managed to snag the legendary grime MC’s verse: “With Skep, I remember he come when I was like twelve; he come to Northampton – and like Northampton, nothing really happens there. And he come and done a show and (…) for all my boys back home as well, It’s like ‘Yo, as if!’” he recounted.

“I think I sent him like three other tunes before and he was like, ‘Uh, yeah.’ I sent him this (Inglorious) and he was like, ‘This one’s hard.’ And then from that, I thought he was taking long. I was like, ‘Nah this verse, it never coming.” And then he was like, ‘Bam.’”

Skepta and Slowthai are two completely different people. As for Skepta, whereas in earlier stages of his career he welcomed characterization as a brash, upstart MC with no filter, his current approach is noticeably recessive – especially when it comes to politics. Slowthai, on the other hand, hinges his entire artistic persona on the rock of not only hating what Britain has become, but being loud about it. In one of the 18 interviews Jon Caramanica held with Pop Smoke’s closest allies, it was further recalled that while meeting with the up-and-coming rapper, 50 Cent had to talk Jackson down from going further along the violent path he found himself treading. Although Skepta and Slowthai’s meeting comes in an utterly different contextual package, one cannot help but see a similar dynamic between the crevices: Frampton acknowledges Skepta as a superior who has gotten rich, and is willing to humble himself just enough to not – whether literally or reputationally – die trying.

As he sits on the cusp of his second studio album set for release this February, Slowthai’s reputation is an unconventional concoction of anti-heroism and childlike bliss, loved equally at home and abroad. His first album proved that he doesn’t care nearly as much about the consequences of his actions as he does the fun he has doing them. His upcoming project will have to confirm whether he can keep up the gambit – and if all dimensions of his fanbase will be willing to stay along for the ride.

Suge Knight, 6ix9ine, Pop Smoke, and 50 Cent have each held the very position Frampton now finds himself existing in. Momentum is in Slowthai’s favor. He can get rich. Or he can die trying.