Deep Dive: Revisiting the Prospect of a Kanye West Presidency

Kanye West has the intrigue to make voters glance at his name on a ballot. Is it possible that he – or any non-political cultural figure ever to come – could one day muster what it takes to make them fill in the bubble?

SAMUEL HYLAND

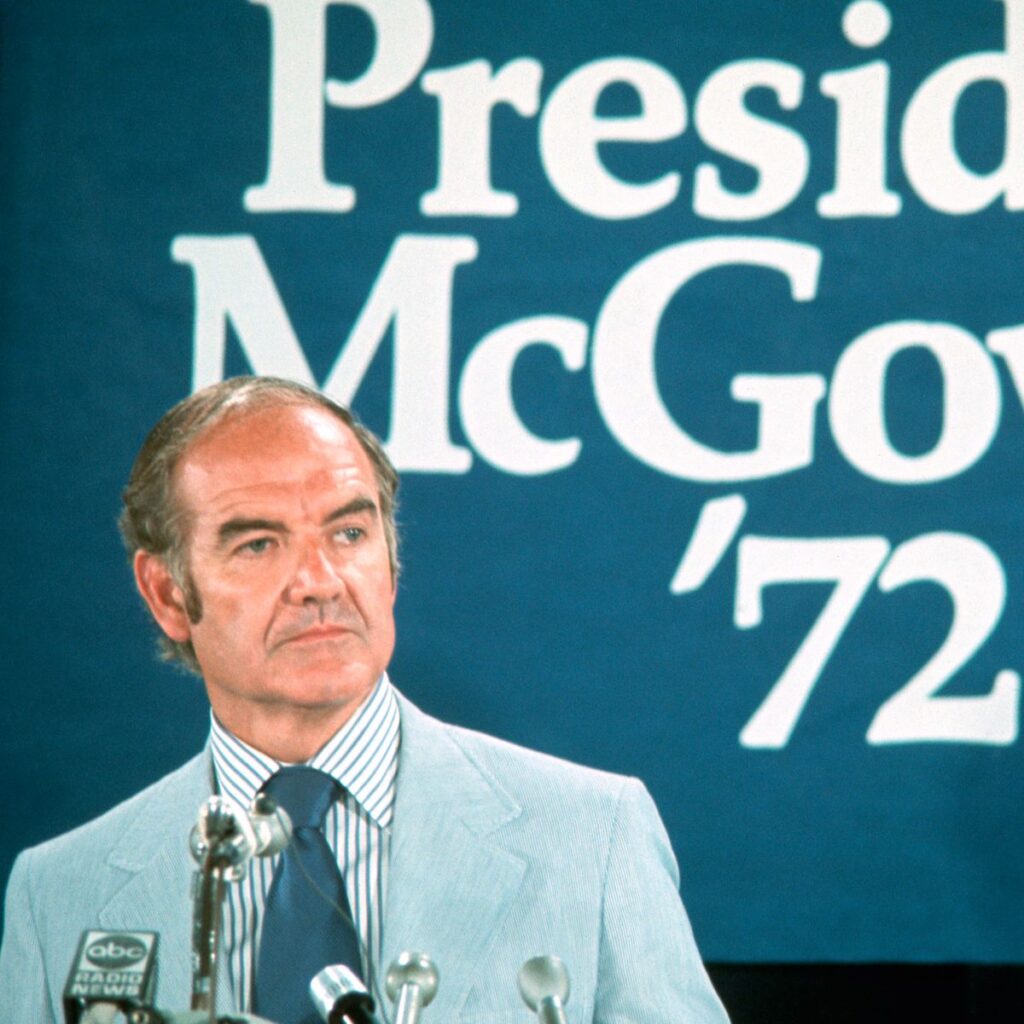

One of several compelling characters in 1972’s infamous presidential election, Democratic Party candidate George McGovern’s reputation in politics was marred by a paradox proven only more and more absurd with the evolution of culture: genuine behind closed doors; questionable in front of a camera. McGovern was an honest man, wearing a rare cloak of candidness into the thick of a battlefield riddled with deceit. Several years before he was murdered, Robert F. Kennedy called him “the most decent man in the Senate.” His characteral makeup was one that, while politics en masse barrelled on towards not only the idea, but the expectation, that candidates were lying to the public and being honest behind closed doors, flipped the entire American civic conversation on its ever-evolving head. He said what he meant. He did what he said he would do. He was the best gentleman in the race.

But this was not, as Hunter S. Thompson put it in his novel Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72, “quite the same thing as being the best candidate for President of the United States.” For that, Thompson mused, McGovern would need “at least one dark kinky streak of Mick Jagger in his soul”: in essence, the slightest tangible ounce of invigorating public presence on television and radio. As remains – arguably even more so – the case in America’s 21st Century political climate, there is zero need for accountability if you can’t sell it on TV. In an era that takes the revolutionary immediacy-driven cultural cache of the 1980s, and nudges it several seemingly impossible hyper-indulgent notches higher, there is not much passion unless there is first a passionate character for it to attach itself to. Politically, the dynamic quite often dies out when rendered to a one-or-the-other skeleton – radical ideas don’t get into office behind modest mouths; provocative loudmouths don’t get into office with moderate, play-it-safe rhetoric – and the exact general ebb and flow is one that is derived from none other than the broader entertainment business.

“He’s too unpredictable to hold any position in a political office.”

The seeds for such a construct were far beyond just sown in 1972, though, and despite it not being 2020, the year’s campaign remained just as defined by the screen as it was the polls. “The main problem in any democracy is that crowd-pleasers are generally brainless swine who can go out on a stage and whup their supporters into an orgiastic frenzy – then go back to the office and sell every one of the poor bastards down the tube for a nickel apiece,” Thompson continued in Fear and Loathing. “Probably the rarest form of life in American politics is the man who can turn on a crowd and still keep his head straight – assuming it was straight in the first place.”

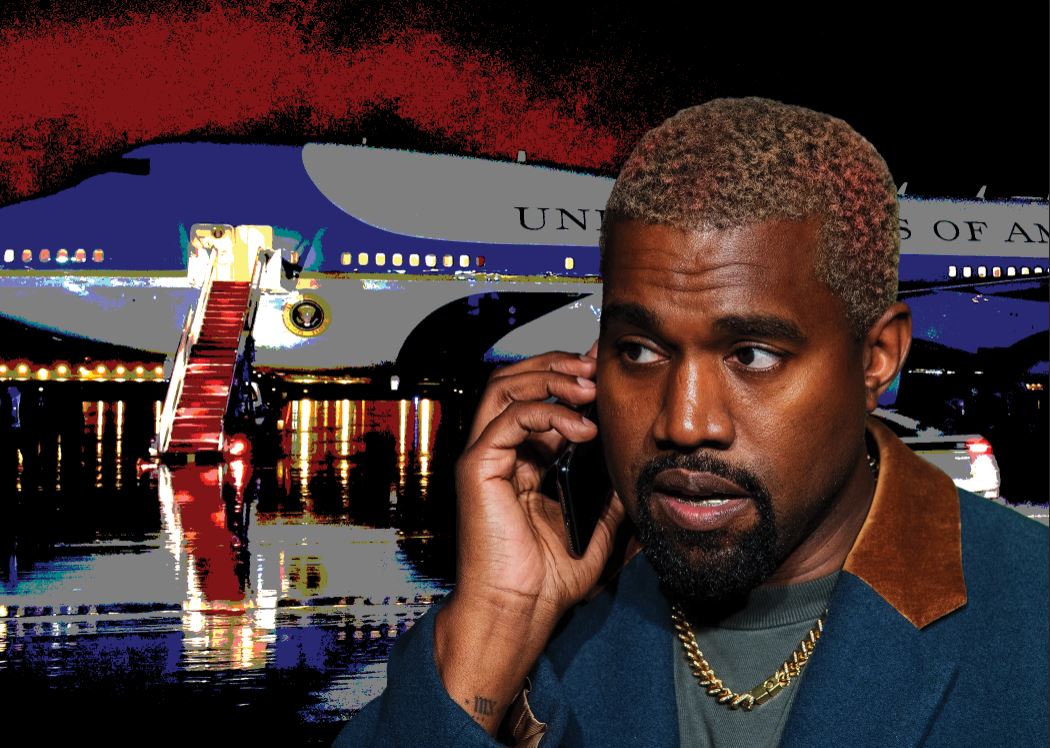

The question of whether Kanye West had his head straight was long a topic of debate before any political plans of his were made public. When West announced that he was joining Donald Trump, Joe Biden, and Jo Jorgensen in the race to become President of the United States last year, the news was all at once both shocking and ordinary: shocking in the sense that a hip-hop figure was making a run at the White House; ordinary in the sense that that hip-hop figure was Kanye West. Kanye West boasted (and still does boast) one of, if not the single most erratic track record(s) of incidents, eras, and chaotic episodes across the combined careers of his colleagues. In 2009, he infamously lugged a full bottle of Hennessy cognac to the VMA Awards, consequently setting the stage for a pivotal mid-speech interruption of Taylor Swift in which he suggested the trophy in her hand rightfully belonged to Beyoncé. In a 2016 music video he defended as “artistic,” he featured a vast expanse of nude celebrity wax figurines (including Swift, alongside a cast of characters ranging from Rihanna, to Caitlyn Jenner, to Bill Cosby) sleeping with each other in a larger-than-life bed. Months after announcing his run for President in 2020, he would go on to urinate into a Grammy award lodged inside of a toilet bowl for his 30 million Twitter followers to see, before also publicly uploading all 113 pages of his Universal Records contract onto the same platform.

It was not rare for this unpredictable nature to cross the line into political territory. In 2005, appearing on a live broadcast purposed to crowdfund support for victims of Hurricane Katrina, he famously stared into a television camera and stated that “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.” The Kanye West of that point was an upstart young rags-to-riches exemplar, fresh off of an impressive first two albums that all-but-undoubtedly carved his place as ‘up next’ in a pantheon of distinguished names hailing from the same hip-hop ethos. The moment read, in this context, as an outstretched arm to a lifestyle lavishly graduated from; it was a feel-good inkling that the kid from Chicago hadn’t let the money get to him. Years later, yet, as his stature drew him further away from his humble origins, and deeper into the limitless confines of his own mind, his political inclinations appeared to follow suit. It was a transformation that began to publicly manifest itself at the onset of the Trump era. In one of several early controversial outbursts that defined this period, West raised eyebrows by claiming in an interview with TMZ that slavery was a “choice.” Hosting Saturday Night Live as a fill-in for Ariana Grande in 2018 – all the while sporting a red ‘MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN’ baseball cap – he triggered furious reactions online after going on a rant that touched on links between Welfare and the Democratic Party, whether or not America is racist, and passionate rebukes of memes that likened his situation to the movie Get Out. West had been a friend, then eventually a firebrand political supporter, of Donald Trump over the course of his erratic re-entry into the civic conversation from the previous decade. Much as he simultaneously grew to become with music, he was not nearly as concerned with making sense as he was with getting his mind translated into the real world – those who were meant to understand, would understand; and those who did not understand, would understand later.

In a 2018 New York Times profile fittingly titled ‘Into the Wild with Kanye West,’ the rapper opened up in-depth, for what had then been one of the first times, about his newfound outlook and the various factors that went into it. “-because you’re black, because you make very sensitive music, because you’re a very sensitive soul, it was like an arranged marriage or something,” he told Times pop music critic Jon Caramanica, referring to external pressures for him to cast his vote for Hillary Clinton in loyalty to the Democratic Party. “And I’m like, that’s not who I want to marry. I don’t feel that. I believe that I’m actually a better father because I got my [expletive] voice back, I’m a better artist because I got my voice back. I was living inside of some universe that was created by the mob-thought, and I had lost who I was, so that’s when I was in the sunken place. You look in my eyes right now – you see no sunken place.”

In reality, Kanye West had announced that he intended to run in the 2020 Presidential Election several years before he tweeted it on Independence Day that summer. At 2015’s VMA Awards – the same event that bore witness to the Taylor Swift incident six years prior – he concluded a heartfelt 11 minute-long acceptance speech for the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award with the brazen assertion that “yes, as you probably could’ve guessed by this moment, I have decided in 2020 to run for president,” promptly walking off-stage to a smattering of applause that seemed to take the gesture as either a gimmick, or a case of wishful thinking.

In the respective worlds of music media, social media buzzings, and lunch table conversations alike, whether or not West was serious tended to prove frustratingly obscure. But still, in the threatening reality of it all, either side of the coin never seemed to fully and definitively leave the realm of a joke. I myself, for instance, was in seventh grade when I first learned of West’s initial announcement… not on the morning news (I was unfortunately not allowed to stay up and watch West’s speech live), but several hours after school, on an app dedicated to memes. No matter how serious Kanye West was about becoming the President of the United States, nothing he – or we – could do would ever make us remotely as assured as he was.

The traditional candidate for office builds their reputation via strategically calculated public appearances, planned down to the final few handshakes, in which intentional motifs are brandished in the stead of even more intentional rhetoric – behind which lies a meticulously manufactured personality, built specifically for the television screen, more or less turned off behind closed doors. Kanye West, on the other hand, never truly had a readily available off button from the public eye since the moment he mounted celebrity culture’s summit. And, especially for someone of the prolific stature he has grown to attain, any and all margins of his presence possibly allocated to privacy have worn increasingly thin as time has gone on. It’s the reason why at the height of his bout with the “sunken place” in 2018, his long-winding retreat into Wyoming was a highly publicized faux-escape: what would live merely as “time away” for the ordinary person became, once given into the hands of concerned fans and spectators alike, the cinematic culmination of a large-scale Kardashian family hostage situation ostensibly verbatim to that of the year’s most captivating horror film. Taking Kanye West seriously as a candidate meant separating him from his celebrity. It was a ship that had sailed long before we knew we would have to catch it – and even when it came back to shore years later, any means of doing so remained inept.

“He’s the goat and a genius. He would try to end systemic racism to the best of his ability.”

📺 📺 📺

In a recent poll conducted via social media, Sammy’s World asked its readers whether there was any chance – no matter how small – that they would vote for Kanye West in an election during their lifetimes. Of those who participated, 64 percent voted no, and 36 percent voted yes. Most explanations for the majority vote almost precisely emulated concerns expressed by the broader American public upon hearing of West’s run – some including that “He’s too unpredictable to hold any position in a political office,” that “he has legit mental illness,” and that “Kanye not dropping Donda. I ain’t voting for him.” On the other end of the spectrum, too, rationales in support of voting for Kanye West also emulated the most common justifications of real-life Yeezy voters – including (but not limited to) “for the culture,” “if he is the only option,” and “He’s the goat and a genius. He would try to end systemic racism to the best of his ability.”

For as many political, moral, and mental flaws as Kanye West has exhibited over his rocky journey to the peak of the arts, the most common through-line in motives for tossing him a vote is one that centers on a growing nucleus between culture and statecraft. In a recent New York Times Magazine profile of the notoriously right-wing Black Rifle Coffee Shop, Times writer Evan Zengerle enlisted Steve Callander, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, to provide insight on the heightening urges of corporations to lean into social causes. “There’s an imperfect line between what’s political and what’s cultural these days,” Callander said. “Companies definitely want to tap into cultural trends, because that’s how you connect with your customers.”

Politics and the arts are inherently independent of each other, and so, consequently, attempts to merge the two could not possibly be any more transparent in their purely benefits-driven motives: you don’t take a New York City mayoral candidate seriously when they use an A$AP Mob track in their campaign ad, the same way you don’t take an arts-centric corporation seriously when it changes its profile picture to a rainbow-adorned variant for the month of June. Much like Pepsi did in the mid-20th Century to get a leg-up on Coca-Cola in branding contention, many companies (and politicians alike) have learned not to sell the product, but the image – and for that matter, one that appeals as fittingly as possible to the most profitable demographic. In Kanye West’s case, his own appeal lies in the difference: even if he sticks his head as far into politics as he can manage, because of the extent of his contributions to it, Kanye Omari West will always be the epitome of a freewheeling, self-sufficient creative culture that just so happens to be, in fact, inherently apolitical. A Kanye West presidential bid may be funny to visualize – but whereas most intersections of politics and the arts cannot help but be obvious in their insincerity, one is forced to note that West doesn’t come off like a local mayoral candidate playing city-borne hip-hop tracks in his campaign ads. Like McGovern, he has nothing to hide. Unlike McGovern – much to his advantage – he just so happens to be good enough on TV for it to mean something.

As deep into diplomatic discourse as he either is, or would like us to believe he is, the less-pragmatic context that furnished West’s ascent to legitimate Presidential candidacy is an irremovable shadow – one that simultaneously cools loyal supporters into comfort, and obscures detractors from ever being able to see the vision. Kanye West may no longer be the profanity-laden, Hennessy bottle-toting provocateur that America knew him as over the majority of the 2010s, but because of how prolific that character was, it is impossible to look his current face in the eyes and not see its history staring right back at you.

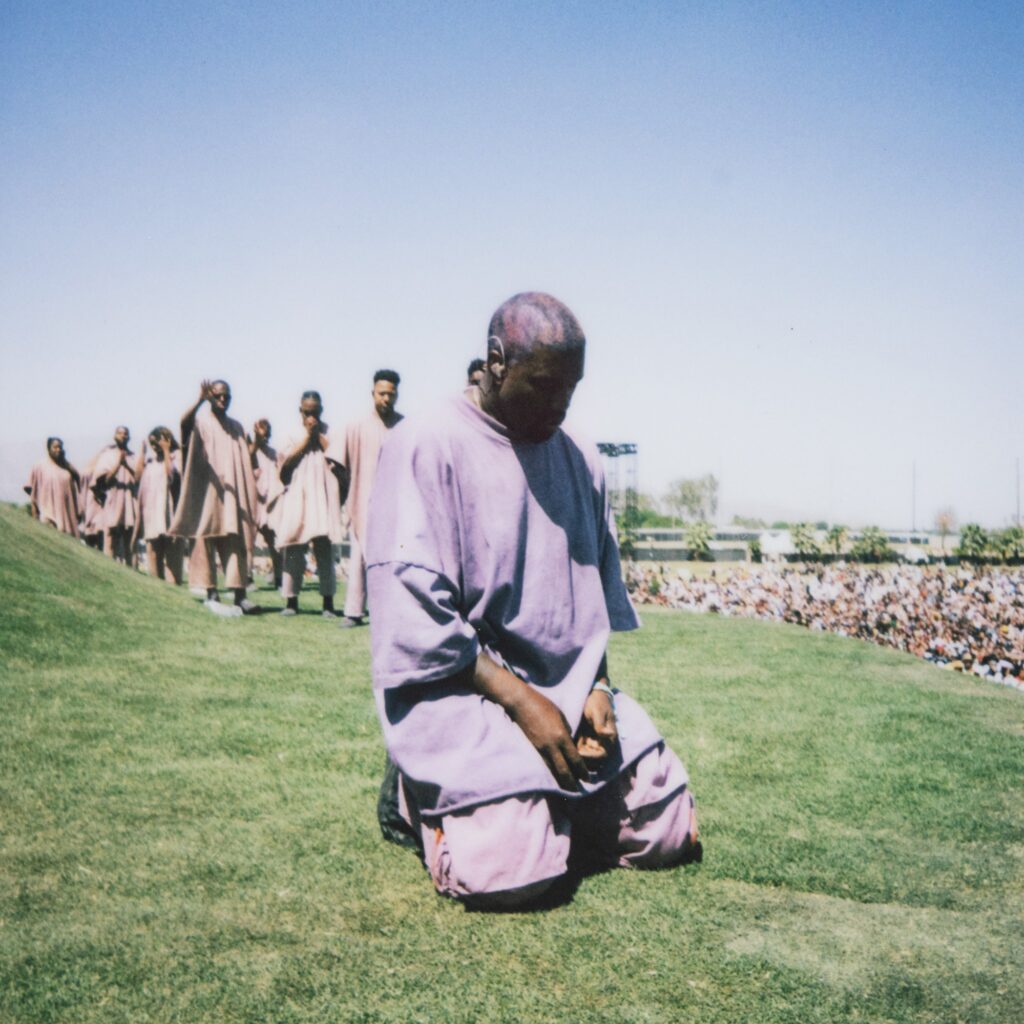

Following the release of his 2019 gospel album Jesus Is King, for example, West was invited to speak before a jam-packed Sunday morning crowd of 16,800 parishioners at Houston’s Lakewood Church (formerly home of the Houston Rockets), as part of a weekly broadcast by the famed televangelist Joel Osteen. West was, at the time, an openly devout Christian, seeming to focus all of his energy on the religion in the little time that he spent in the public eye, whilst putting on an intricate series of performance art-based “Sunday Service” events that saw secular celebrities like A$AP Rocky, Virgil Abloh, and Justin Bieber passionately embrace Christianity in full view of their otherwise-oriented followings. Even though West was enacting a movement churches across the country had likely spent years yearning for, there was mass hesitance among Christian communities when it came to embracing him as part of their inner folds. In one Religion Unplugged study of Facebook comments from Lakewood parishioners following West’s appearance at the congregation, it was found that not all in attendance for his segment were big fans.

“In Kanye’s mind – and in a lot of fans’ minds – every Kanye album release, or release of a new clothing line, is a new era. And for him, that is what he understands to be the process of being an artist, or being a famous person, or, as he would say – in his own words – a genius.”

Alphonse Pierre, Pitchfork

“God hasn’t transformed this man…this guy is just trying to keep himself relevant,” Lakewood member Michael J. Seale wrote in one response. In retaliation to a mid-service quip by Osteen that “When you’ve got Kanye defending you, you’ve made it, man,” churchgoer Monica Johnson also commented: “Joel? Seriously?? I thought you said, God is your defender?! What’s wrong with you? Suddenly you’ve become secular and self serving.” A palpable air of nervousness is present all throughout the video of West’s 20-minute monologue: Osteen seems to glare at his co-star with a jitteriness that is prepared to snatch the microphone at any given second, and the audience appears stumped at some points about where to draw the line. (To be fair, West did dance around questionable territory over the course of his address – including proclaiming himself “the greatest artist that God has ever created,” and sternly shushing a crowd that was just beginning to unleash its most convicted applause – “I would like for everybody to be completely silent as God flows through me while I speak.”)

In a 2019 review, Pitchfork critic Alphonse Pierre referred to ‘On God,’ the fifth track of Jesus is King, as “an anthem for pastors with a pair of Off-White VaporMaxes in the closet of their multimillion-dollar homes.” “Kanye,” he continued, “wants us to think he’s a new man—no more cursing or Grammy worship—though a close look at this song’s lyrics prove that he hasn’t changed much.”

“As much as Kanye is a figure outside of his music and his personality, all this is put up with because so many people care about his music,” Pierre told Sammy’s World in a phone call. “Maybe they graduated from high school during this album, or they fell in love during this album, or they went to school during this album. It’s a very consistent catalogue that’s going on 15-20 years. And when somebody is that embedded, it’s hard to completely wall them off.”

The question becomes one of tolerance: how many times has West sought to convince followers that he had become a “new man,” and how many times has his music been the sole factor keeping supporters attached to an ever-wobbling tightrope? Disregarding how successful (or unsuccessful) he would go on to become in each endeavor, every time that West has sought to abandon an old version of himself for a new one – whether it be a cryptic recluse, a prolific high fashion staple, or a devout independent religious leader – he has found himself in the all-too-familiar position of an outsider looking in. Such situations offer little middle ground between vehement support and furious disapproval. (“I think that my personality and energy mirrors Nat Turner,” he told Caramanica in the aforementioned New York Times interview, upon being asked how he usually felt when he knew experiments didn’t work. “But I guess we’re all martyrs eventually, and we’re all guaranteed to die.”)

His presence in politics was, at the time that he announced his 2020 run, defined by a similar construct: Kanye West did not fit into the conventional mold of the U.S political process, but in an increasingly monotonous whirlpool of old men who did – suit-and-tie clad Ivy league graduates who said all the right things, shook all the right hands, and wreaked all the right social havoc – his stark unfitness was far overtaken by his unmatchable shock value. In a 2020 New York Times opinion piece entitled “The Real Divide in America is Between Political Junkies and Everyone Else,” Stony Brook University political science professors Yanna Krupnikov and John Barry Ryan argued that excessively passionate militancy on both sides of the aisle was pushing target demographics away from discourse more than it was inviting them in. “This gap between the politically indifferent and hard, loud partisans exacerbates the perception of a hopeless division in American politics because it is the partisans who define what it means to engage in politics,” they wrote. “When a Democrat imagines a Republican, she is not imagining a co-worker who mostly posts cat pictures and happens to vote differently; she is more likely imagining a co-worker she had to mute on Facebook because the Trump posts became too hard to bear.”

Kanye West’s candidacy was a timely beacon for the co-worker who, no matter what party, was tired of having to mute colleagues on Facebook who threatened more and more every day to pull the blanket of politics completely and totally over what was once unadulterated life. While Donald Trump, Joe Biden, and Jo Jorgensen were speaking for the political junkies, Kanye West seemed to be the only one who was doing so for everyone else. And beyond music, the fact that people still somewhat took him seriously – in spite of how little sense, if any at all, he often made – was a testament in itself to how badly they needed to be spoken to.

As fate would very well have it, yet, this was not quite the same thing as being the best candidate for President of the United States. By the time that ballots closed in early November, Kanye West had only earned a meager 2 percent of votes across the country. One of the stark similarities between McGovern and West was the employment of grassroots campaign tactics – something that Kanye took to an entirely new level – and even in one of few places that the West-McGovern venn diagram finds middle ground, McGovern, even though he may not have been good on TV, comes out with the upper-hand: in an America that is ingrained in traditional suit-and-tie politics, traditional suit-and-tie politics will always win. No matter how terrible it looks on TV.

Kanye West’s final tweet (to this day) following a lengthy spiel of several hundred spanning his entire campaign was a single mannerism – KANYE 2024 – accompanied by an image of his shadowed face backgrounded by the electoral map of his defeat. It’s a still-standing question mark at the conclusion(?) of a period in which not only the limits of political rhetoric, but of political audacity, were put unrelentingly to the test. Kanye West has the intrigue to make voters glance at his name on a ballot. Is it possible that he – or any non-political cultural figure ever to come – could one day muster what it takes to make them fill in the bubble?

“You never know what crazy shit will happen after these past few years,” one reader responded to the aforementioned Sammy’s World poll. “Anything’s possible!”

🎥 🎥 🎥

“He has legit mental illness.”

As Kanye West nears the release of Donda, his hotly anticipated studio follow-up to Jesus Is King, dabblings into the public eye, increasing incrementally in length and severity, are becoming more and more frequent. This past week, Kanye fandoms and social media at-large alike were lit ablaze by news of an exclusive, invite-only listening party for the album, held at a Las Vegas church. It was not long before extensive track-by-track rundowns began popping up all over Twitter, delivered alongside smugly listed insider details: no cell phones, a Baby Keem feature, etc. A day after the Las Vegas listening party made its rounds on the internet (as was prophesied by many of its attendees), during ABC’s telecast of Game 6 of the NBA Finals, a familiar voice crooned “He’s done miracles on me” throughout a newly premiering Beats commercial featuring the famed Olympic track athlete Sha’Carri Richardson. Today, two days removed from what was, very likely, the most anticipated non-Super Bowl commercial in quite some time, West is scheduled to premiere the album in front of a sold-out crowd at Atlanta’s Mercedes-Benz Stadium.

As many have publicly mused, there is something tangible about this specific album rollout that feels different from others we have seen precede recent Kanye West projects. Putting a finger on it would mean identifying the freshly broken constant: as of the past few years, whether borne from mental instability, familial troubles, or public-facing conflict, West has appeared to stumble into new chapters of his artistry rather than deliberately curate them. It is a common anecdote in hip-hop circles that his revered 2010 LP My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy would have never come to fruition had it not been for his aforementioned VMA Awards debacle, just as it has become legend in Kanye fandoms that 2018’s Ye was born directly out of frustrations steeped from bipolar disorder. Where the ideal creation standpoint of any artist, regardless of discipline, has evolved to become one of strategic planning and execution, West’s tumultuous several-year run saw his production involuntarily inhibited, existing chiefly at the mercy of his surroundings.

“He’s a person that’s obsessed with the idea of phases and eras,” Pierre said. “In Kanye’s mind – and in a lot of fans’ minds – every Kanye album release, or release of a new clothing line, is a new era. And for him, that is what he understands to be the process of being an artist, or being a famous person, or, as he would say – in his own words – a genius.”

The Kanye West of right now appears to be somewhat freed from the circumstance-borne shackles of his most recent creative endeavors – back to being creative not as a reaction to something, but as a catalyst worth being reacted to.

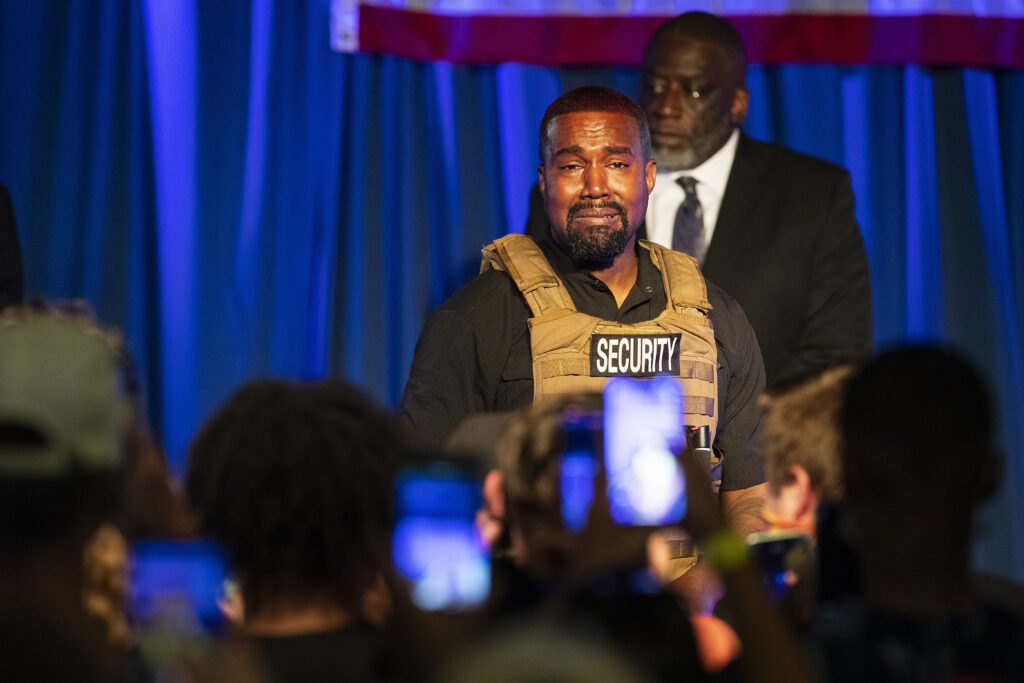

It’s a far cry from the energy surrounding West’s second most recent string of emergences into the public canon. In 2020, after an initial campaign launch that garnered its publicity primarily from (arguably bad) press – in his first interview since announcing his candidacy, Forbes reported that he considered COVID-19 vaccines “the mark of the beast,” that his political plan was most influenced by the fictional country of Wakanda, and that he planned to run under his self-created ‘Birthday Party’ “because when we win, it’s everybody’s birthday” – West elected to host a hastily-prepared public forum in South Carolina as his first official political rally. On a floor-level front area, donning a bullet-proof vest and the term ‘2020’ shaved into his head, he paced back and forth before a lone American flag plastered onto a curtain behind him, stopping at some points to let his emotions fester, and at others to be reduced to tears at the thought of aborting his daughter North.

At one of several points in the event that made for discussion on social media sites, West invited a young African-American woman onstage as part of a question-and-answer segment planned for the evening’s program. In a video later shared to Instagram, she claimed to have posed a question about gun reform, only to have West spew out random facts and brag about himself. He would later go on to address the crowd again, this time layering them with false information, with the young woman interrupting him from the audience to yell out the truth each time he did so. It is at this point that the chaotic viral video starts: West screams something about TMZ and his heckler wanting to “be that same person,” then storms off stage after invigorating the crowd with a remark directed at her mask: “And your face is covered, so we don’t even know who you are!”

It’s a singular moment that wholly epitomizes the fundamental ethos of West’s entire candidacy: it was chaotic by default, a constant tug-of-war between Democratic values (he vowed to “cure homelessness and hunger”) and conservative undertones present to cancel them out at every turn (along with being a longtime Trump apologist, his campaign was suspiciously funded by a large number of Republican operatives). With all notions that seemed to be clear-cut, there were layers of cryptic vernacular to be sifted through, too – one early piece of campaign art featured unexplained images of Vogue editor Anna Wintour and actress Kirsten Dunst. (“What’s the message here,” Dunst would later tweet in response, “and why am I apart (sic) of it?”)

Still, yet, in spite of his unpredictable nature, West was regarded by voters and government officials alike as capable of having a legitimate effect on who would be the next President of the United States – to a point where one of the Democratic Party’s primary fears going into election day was that West could very capably siphon off enough votes from Joe Biden to ensure a Trump victory. That West was legitimized to such an extent, and not hastily dismissed even from his very first questionable showing, is a living example of a longstanding political dynamic that only seems to come back stronger as time draws on: the winner of a race may not any longer come down to the best candidate, but the victor of a “pick your poison” proposition preceding inevitable death.

“How many more of these goddamn elections are we going to have to write off as lame but ‘regrettably necessary’ holding actions?” Thompson writes early on in Fear in Loathing. “And how many more of these stinking, double-downer sideshows will we have to go through before we can get ourselves straight enough to put together some kind of national election that will give me and the at least 20 million people I tend to agree with a chance to vote for something, instead of always being faced with that old familiar choice between the lesser of two evils?”

Thompson’s question, as rhetorical as it may be purposed, is a dystopian one that presents itself with increasing volume at every opportunity. Many may argue that all politics are inherently evil, and that, as mentioned before, insincerity in public and the opposite behind closed doors is not a surprise, but an expectation in civic duty. There has never been, nor will there likely ever be, any such thing as a one-hundred percent honest candidate – but even with the asymptote in play, time pushes us eternally further away from it, rather than closer. Think of it as a moth to a flame at dusk: the goal, or natural light, that we seek, is government for the benefit of all constituents, but in the light’s absence, politics en masse gravitates towards the deadly fire of self-servitude.

“What Kanye West’s celebrity did for him was offer a pre-made pedestal, set to launch him – even despite joining the running months late – into the main event of a match card he wasn’t even in the arena for a week prior.”

2020 saw Thompson’s “lesser of two evils” grievances played out on a scale so grand that even the ‘everyone else’ of Krupnikov and Ryan somehow found themselves clued into the grim realities at-hand, many consequently making the decision not to vote. “I don’t feel represented by the candidates the parties in power keep offering up,” one conservative millennial who chose to go anonymous told CNBC last year. “And I won’t vote for a lesser evil.”

Kanye West’s run came as a stark harbinger of just how dystopian such a worsening political makeup could grow – for many, he was the lesser of the lesser of two evils; and even amidst his own personal chaos, he inadvertently represented not only how low we were, but the terrifyingly undefined chasm of how much lower we could possibly go. West’s 2020 candidacy additionally presented yet another mutant layer of apocalyptic statecraft we had only begun to truly unravel in the 21st Century: the power – and danger – of celebrity in the pursuit for rulership.

Had someone relatively unknown outside of politics sought to run for office with the same exact values, the same exact gameplan, and the same exact erratic unpredictability of West in 2020’s election, it is beyond likely that they would not have passed the stage of getting enough petition signatures. What Kanye West’s celebrity did for him was offer a pre-made pedestal, set to launch him – even despite joining the running months late – into the main event of a match card he wasn’t even in the arena for a week prior. Before he had said much publicly about his policies, stances, or values, the same internet that had furnished his rise to the pinnacle of hip-hop culture was now making sense of a situation (for him) that he himself often proved to lack full grasp of: within days, theories began circulating that he had feigned support for Trump to convince him to free fellow rappers from prison; there were recaps to Kim Kardashian’s various initiatives to do the same, namely with Meek Mill; what registered as a joke in 2015 quickly seemed to become deathly serious.

Then, of course, Kanye West opened his mouth and everyone was laughing at him again.

Still, however, one is forced to think: what if Kanye hadn’t said anything? If Kanye West were to never say anything again after announcing his candidacy on Twitter, the internet naturally becoming his de-facto campaign manager, what influence would any opposing man-made political team have against his legion of virtual spokespeople? There was a point where Kanye West took the baton from his own celebrity, and tripped over himself while trying to fill the gaps. What if his celebrity ran the whole race? It is much more appealing in retrospect to vote for the idea of Kanye West, than it is to vote for Kanye West himself.

“Some sort of cultural shift would have to happen,” Pierre said, when asked what it might take for West to someday become President. “Whether with people having some huge backlash to something that is going on politically- or even with culture as a whole becoming even more obsessed with the idea of celebrity and fame, which we already are.”

The notion paints a picture that wouldn’t be too out of place in a science fiction novel. There is a very rapidly thinning line in celebrity culture between reverence and idolatry, and as the latter (affectionately referred to as “stan culture”) becomes more and more of a common standard, the power afforded to such figures grows to dangerous levels. In one case popularized by a Twitter account dedicated to “Dudes Taking Ls,” for instance, a longtime subscriber to a female content creator’s OnlyFans account paid $10,000 to hug her in-person. When all was said and done, she and her boyfriend had used the man’s money to travel the world.

There is a vast number of celebrities with far cleaner track records than West, many of which also hold legacies that far outlast who they may be in reality. If the concept of a celebrity running for President is essentially one of their reputation – not them themselves – standing trial, the outlook of our increasingly celebrity-obsessed culture gestures toward a future in which popularity, not money, becomes the primary currency of the socioeconomic ladder. Good reputations sum up to power and wealth, while not-so-good ones sum up to neglect and destitution. In a society where money determines much of who plays these roles, such a forecast is both refreshing and depressing: as much as we may be able to escape its capitalistic manifestations, we will never be able to escape human nature itself.

The intriguing thing about Kanye West in the context of such determinism is that, in the middle of an era that sees practically all people, whether famous or not, attempt to appear immune to this human nature, Kanye West embraces it in full view of the audience he has cultivated. This does not mean that it is always intentional. Kanye West does not strategically schedule life-altering mental episodes with pen and paper, nor does he look into his dressing room mirror prior to the VMAs and calculate exactly the first public domino to fall on a groundbreaking album’s rollout. Rather, much like the quality McGovern’s appeal banked on in 1972, Kanye West is very obviously doing it on the fly. His spontaneity does boil over to unspeakably weird melting points. But as politics grows to adopt the values of the television that has become its home, it helps to view it all as the intricate set to the late-night special that is the United States of America: while stiff, elderly characters are whisked on and off the stage, scripts in trembling hands and optimistic picket sign slogans seared into their memories, Kanye West is somewhere off in a corner talking about birthday parties, Wakanda, and Jesus Christ. It doesn’t make any damn sense. But it’s real – and kind of interesting.

“Anything’s possible!”

At one point in his coverage of the 1972 Presidential Election, Thompson made a brief stop in Milwaukee to attend a rally held by George Wallace. He was approached by an excited attendee.

“This guy is the real thing,” the man started. “I never cared anything about politics before, but Wallace ain’t the same as the others. He don’t sneak around the bush. He just comes right out and says it.”

A lot of what Wallace was coming right out and saying (hopefully) wouldn’t do too well in any future elections – “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” doesn’t exactly line up with the vision – but the reaction he was able to garner from his rhetoric speaks a lot to what our candidate’s future will have to ride on, should he choose to pursue the Presidency any further. Kanye West is someone who not only has the honesty, but also the public-facing persona, to amount to much more than McGovern did on a characteral level five decades ago. It has been proven time and time again that people will believe what he says just because he has the nerve to say it. Now, he has to say things that people will believe because they are believable.