The Obsolete Vision of Seventeen

How Seventeen Magazine defined teenage womanhood for America, then failed to survive the firestorm it created.

*🥽RESEARCH🥽*

ORLIE WHITE

The year is 2022: teenage girls are topping music charts, entertaining millions upon millions of social media followers, building beauty empires, being dubbed prosperous entrepreneurs by Forbes, starring in multi-million dollar films, and commanding the attention of the world. While now, their captivation of global attention has come to live as a sort of chronic given, turn the clock back 100 years, and the mighty force of the teenage girl as a consumer, highly receptive and integral in mass media, no longer exists in our culture—let alone anyone else’s. In scrutinizing the characterization of young women as a marketing and purchasing genre, it becomes evident that, over time, teenage girls were sought by society to be defined first and foremost through ravenous consumption of clothes and magazines. Seventeen Magazine laid the foundation of America’s understanding of teenage girls by tending to their psychological and emotional needs, while also simultaneously encouraging and promoting their value as consumers in American society: the finish line was predetermined before the race began, and whether they liked it or not, young women’s wallets were destined to speak louder than their mouths.

“In reality, teenage readers were not concerned with what to wear when they were “off for a cocktail”, “down for the country”, or “out for the evening”, as Harper’s Bazaar envisioned, but rather what they might wear to a school dance, a first date, or when shopping with friends at their favorite department store.”

Long before Seventeen’s 1944 emergence provided teenage girls a comprehensive guide to selfhood, the age group was first conceptualized in a psychological context by G Stanley Hall. In 1904, Hall published Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education, wherein he introduced the archetype of the teenager as being too old for childhood and too young for adulthood. Hall identified many of the emotional hardships and needs that young people often faced during this period, which, in Seventeen’s case, were vital to understand in order to successfully connect with a largely teen-aged readership. For instance, Hall anticipated a heightened state of sensitivity and anxiety: “As the child’s absorption of objects slowly gives place to consciousness of self,” he mused, “reflectiveness often leads to self-criticism and consciousness that may be morbid. He may become captious and censorious of himself and others.” Hall also noted the attention and excitement-seeking needs of adolescents—“At no time of life is the love of excitement so strong as during the season of the accelerated development of adolescence, which craves strong feelings and new sensations, when monotony, routine, and detail are intolerable.”

As Hall suggests, when one enters adolescence, their physiological needs change, and they begin to seek out new experiences, new sensations, and new wonder in the same exact surroundings they’ve been privy to since early youth. Young people between childhood and adulthood are eager to embark on ambitious self-transformations, though it can also be done from a position of fear and discomfort with standings in cultural contexts. It is only by connecting with this emotional desperation, sensitivity, and longingness for validation and acceptance that any medium may harness teen-aged audiences at full potential. The unfortunate gap in this process came when teenagers were invited into retail and consumer spaces without having their emotional needs addressed—more specifically in the form of, for several decades ensuing Hall’s study, advertisers for “junior fashions” promoting clothing to teenage girls in a manner just as condescending as commercial.

While the age group began being discussed in a psychological context after the publication of Hall’s Adolescence, it was through consumer advertisements that the American public at large was introduced to the concept of teenagers – with the spotlight especially bright on teenage girls. Simply put, teenage girls became a familiar concept to American society exclusively through its consumerist economy. Starting in the 1930s, the term “teenager” was slowly incorporated into mainstream American vernacular via advertisers looking to market “junior” fashions to girls who existed between the children’s and women’s clothing sections. As Kelley Massoni writes in Fashioning Teenagers: A Cultural History of Seventeen Magazine, “Retailers and advertisers signaled their awareness of [teenage girls] long before other media. In fact, advertisements for department store ‘teen shops’ and teenage specific department store areas began appearing in newspapers and magazines nearly a decade before any editorial mention of teen-agers.”

“SEVENTEEN is your magazine, High School Girls of America- all yours!”

The New York Times, for instance, first mentioned teenagers not through reporting, but in an advertisement that Lord & Taylor ran on October 4, 1934, for the opening of its “new shop for girls of 12, 14, 16.” Here, Lord & Taylor claimed to “have designed special, suitable things for this difficult in between age… it’s on the Forth (sic) Floor… and we’re calling it the in-be-teen shop.” Teenage girls are written about as if they are an impossible consumer to secure, as the clothes are promoted as “a happy compromise between “mother’s little girl” and the “I’m grown up” idea. Additionally, it becomes interesting to visualize that teenagers looking to shop in the “in-be-teen shop” at Lord & Taylor had to pass through multiple floors of products and clothing sold to women, before finding the collection deemed appropriate to suit their needs and age—all beckoning towards the fact that before the era of Seventeen and other teen-targeted publications, teenage girls were treated as an extension or addition to womens’ markets rather than sought after as their own separate and distinct audience. The context in which teenage girls were introduced to general circles in American society established their identity as being realized, first and foremost, as consumers rather than human beings.

Like advertisers, teenage girls themselves regarded outward appearance as a central aspect of their identities. As Sylvia Simerman found in a 1945 mass survey of American teenage girls titled Clothing and Appearance: Their Psychological Implications for Teen-Age Girls, the majority of girls ages 12-18 gave considerable attention and thought to their clothing. Silverman notes that “The fact that no girl at any age believed she need not give any attention to clothes also indicates that the girls even at an early age were greatly interested in their apparel.” She found that for sixty-two percent of girls, consciousness of their clothes had them feeling “ill at ease” and that eleven percent of young women had experienced feeling so self-conscious about their clothing at events, that they could not enjoy themselves due to overwhelming feelings of inadequacy or inferiority. Even though the stakes of dressing themselves felt extremely high, Seventy-seven percent of a group of 12–18-year-old girls wanted to draw attention to themselves through their fashion. While magazines published prior to Seventeen appealed to teenage girl audiences by offering adjacent trends and direction, they did not provide substantive enough content to guide teenage girls in navigating their collective identity and intellectual development.

Seventeen was not the first magazine aimed specifically at young women in America, but from its debut in 1944, it was different. Seventeen’s biggest competitor was Mademoiselle, first published in 1935. Mademoiselle’s readership was aimed at college-aged women interested in fashion, beauty, and culture. A former staffer at Mademoiselle, Helen Valentine, the first editor-in-chief and founder of Seventeen, opted to use similar content strategies to target high school, rather than college students. Other magazines directed at young girls in the early 20th century included Calling All Girls, The American Girl, The Catholic Girl, Catholic Miss, and Queens’ Gardens. Seventeen, yet, separated itself from its peers in that not only did the publication embrace teenage girls as a consumer market, but it also definitively guided female adolescents on how to navigate their unfurling identities at large. Kelly Schrum writes that even before teenage girls were targeted by Seventeen and its advertisers, they were highly responsive to trends in fashion and media:

“In the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, the teenage girls’ fashion market increasingly created teen-centered spaces for shopping, promoted teenage independence, and offered new styles designed for teenage girls… Although parents and adult observers had well-defined ideas about what teenage girls should wear, high school girls were more receptive to fashion trends, women’s magazines, and advice literature.”

Shrum also notes that the two of the most popular magazines read by teenage girls by the late 1930s were Vogue, and Harper’s Bazaar, both of which, while targeted to an older, more traditional readership of American women, additionally had sections dedicated to clothing trends for their younger readers. Shrum adds that “before magazines in the 1940s, such as Seventeen, emphasized teen sizes and styles exclusively, teenage girls avidly read women’s magazines, translating the messages for high school interests.” Teenage girls were already actively engaged in consuming and engaging with trends in culture and fashion discussed in women’s magazines prior to Seventeen, despite not being catered to as the designated audience of the literature they were beginning to get their hands on.

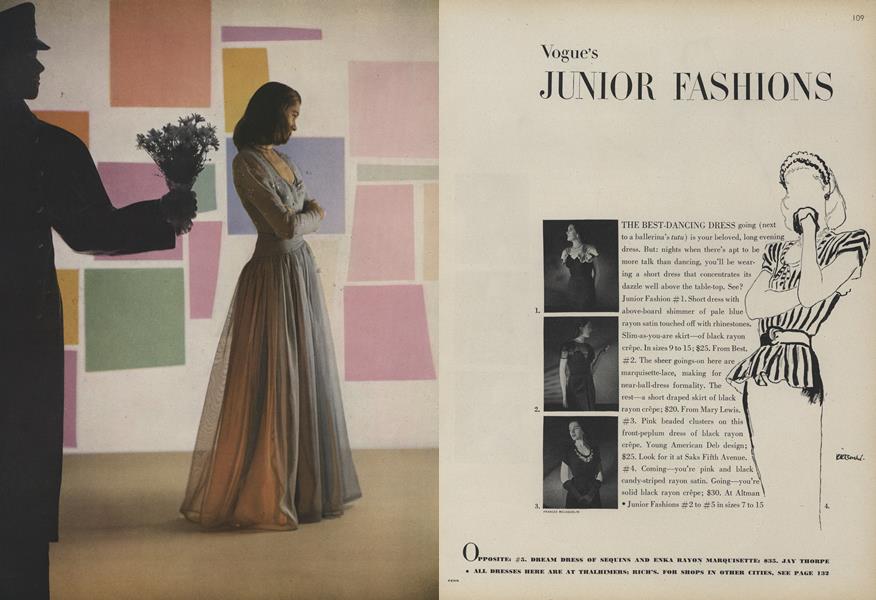

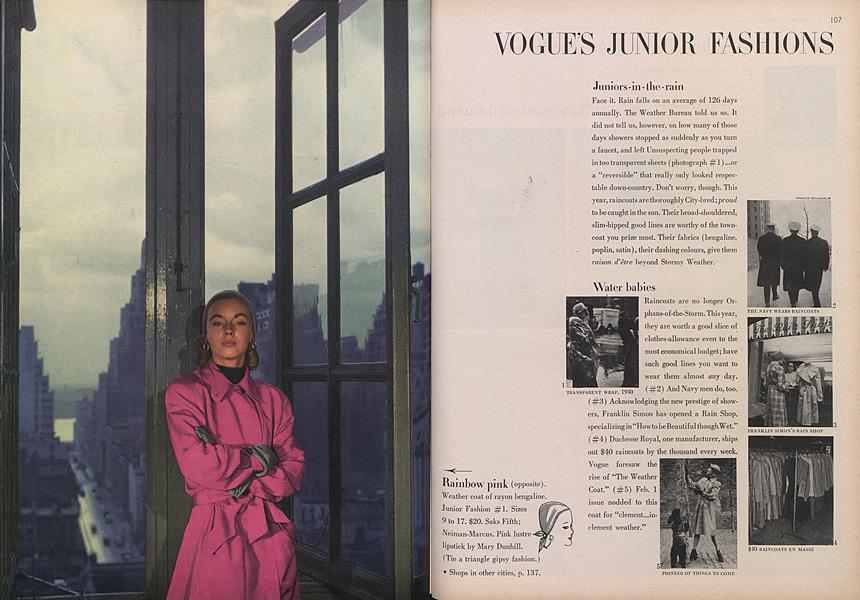

“Valentine was the mature, merrymaking host, and the whole of America’s female youth was invited to the party.”

To understand the success of Seventeen’s ability to connect to high school girls exclusively and unapologetically, it is worth noting that Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar both first presented “junior” content to younger teenage readers in September 1944—the exact same month as Seventeen’s first issue. Both Vogue’s “Junior Fashions” and Harper’s Bazaar’s “Junior Bazaar” sections briefed young readers on the latest fashion trends to engage with, but did not offer content that addressed any deeper exploration of fashion writ-large nor personal choices. The dominant message conveyed in the content for younger audiences in the September 1, 1944 edition of Vogue was that dirndl dresses were no longer in style (“She’s out of hiding!”) and therefore replaceable with dresses that better emphasized one’s proportions.

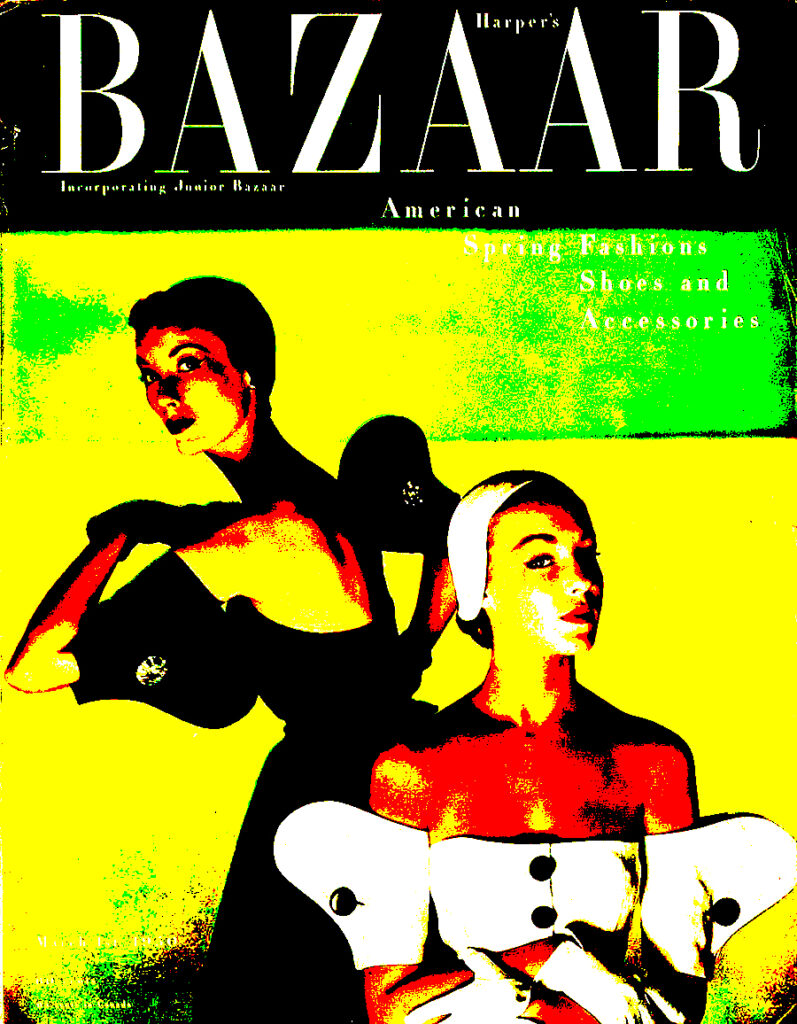

Much like Vogue, too, Harper’s Bazaar’s “Junior Bazaar” spread advertised new clothing for teenage readers to purchase without offering any sort of additional context or guidance. This portion of the magazine, although only a few pages, included a cover page which showcased a close-up of a young girl gazing ahead into the distance while pressing a handful of school books to her chest. The font of the word “Junior” on the cover page of “Junior Bazaar” appears to be a stencil version of the word “Harper’s” in “Harper’s Bazaar” on the issue’s main cover. It appears that, like other department stores, Harper’s Bazaar chooses to see the teenage consumer as a subcategory of the female adult consumer, rather than a unique category in and of itself. With a mimicked logo gracing the cover of “Junior Bazaar,” it is ostensible that Harper’s Bazaar sought to approach teenage audiences in, at the very least, a similar format to the one they manufactured for their targeted adult readership. Because Harper’s Bazaar did not see teenagers as an audience distinctive from adults, they failed to produce content for teenage audiences that accurately responded to and addressed their growing needs.

In reality, teenage readers were not concerned with what to wear when they were “off for a cocktail”, “down for the country”, or “out for the evening”, as Harper’s Bazaar envisioned, but rather what they might wear to a school dance, a first date, or when shopping with friends at their favorite department store. Similar to that of Vogue, the junior content in Harper’s Bazaar demonstrated editorial choices that were disconnected from the emotional, psychological, and social necessities of young American girls in the era of Seventeen’s debut.

At the same time that Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar failed to portray teenage girls as a market entirely distinct from the desires and needs of adult women readers, Calling All Girls, the first general magazine created for young girls featuring “wholesome entertainment” in the form of comics and short stories, also marketed to female teens without addressing the more mature “adult” worlds of beauty, fashion, and culture at-large. While Calling All Girls had cultivated a respectable audience across its short lifespan in the 1940s, it did not access the part of teenage readers enamored by the fantasy of femininity and womanhood promoted in publications like its counterparts. Because Calling All Girls did not target readers solely interested in fashion and beauty, it did not attract enough funding from the big-name advertisers in these realms to ensure what longevity its ethos demanded.

In an exact opposite approach to Calling All Girls’ format of publishing, Seventeen was successful from the onset because it tapped into teenage anxieties and vulnerabilities while delivering its ideal reader to massive advertising companies. Through Seventeen, Helen Valentine, its founder, hoped to create a magazine that would “treat teenage girls seriously and respect their emotional and intellectual needs in addition to helping them choose their first lipstick.” In its first issue, Seventeen vowed to help teenagers make sense of their identity, but before doing so, they introduced businessmen and advertisers to American teenage girl consumers. As Massoni writes, “Seventeen also promoted the teen girl through its education of adults, particularly those in the advertising and retail industries. Because the magazine could not succeed without the financial support of advertisers, selling businesses on the idea of the teen girl as a consumer was among the first tasks at hand.” By appealing to funders prior to teenage audiences, Seventeen positioned itself to meet the needs of the market’s movers and shakers before establishing a relationship with its readers. The foundation of the magazine’s success was built with full understanding of the growing needs of businesses to sell products, coupled with the growing emotional needs of teenage girls. Seventeen methodically and expertly knew how to harness and hook the powerful consumers—businessmen and teenage girls alike—among its readership.

Prior to its initial launch, Seventeen conducted a campaign to promote the idea of teenage girls to retailers and organizers, championed by Estelle Ellis, the magazine’s promotional director. Reflecting on this, Ellis recalled that “Because there was no awareness- not only of teenagers- but there was no awareness of teenage girls, there was no awareness of how they dressed, or the clothes they needed… So it’s hard to believe it, but at the time, it was totally… new terrain.” Inspired by how Mademoiselle tailored advertisements and content to a specific audience of female college students, Ellis sought to introduce advertising and marketing into, now, the teenagers’ niche. Understanding that society was moving into an economy driven by consumer demands, Ellis encouraged retailers to “know thy buyer” and aimed to introduce the teenage girl to advertising companies as well. Massoni notes that “Instead of saying to retailers, “You make [name of product] and we can sell it to teen girls, Seventeen said, “Teen girls need [name of product] and if you make it, they will buy it.” Seventeen was interested and fascinated with understanding their audience for the sake of not only producing suitable content, but also by sharing their insights of teenage audiences to a market that was ready to pounce.

A few months after its inaugural issue, Seventeen gathered information on their audience to translate and present to advertisers in a novel way. The magazine created a profile named Teena, as a specific embodiment of the average teenage girl consumer and reader of its content. Valentine also hired a consulting firm called Opinion Research Corporation (ORC) to gather substantial information on teenage girls. With the data evidence in her hand, Ellis packaged her ideal of the archetype into the “Teena” figure, whom Seventeen introduced to potential advertisers as an embodiment of the adolescent standard. In courting potential business partners, Ellis created a guide to Teena dubbed Life with Teena: A Seventeen Magazine Survey. In the first chapter of Life with Teena: A Seventeen Magazine Survey, Teena was defined in explicit terms to advertisers, through which advertisers were expected to develop a better understanding of Seventeen’s target market:

“Our girl Teena is sixteen years old. She’s five feet four and a quarter inches tall and tips the scales at 118 pounds. She goes to a public high school, expects to graduate next year at the age of 17 and go on to college with a B.A. or B.S. in mind… Teena could work her way through college if she had to… she earns money even now, minding babies after school. And it’s not just “pin money” she’s working for either… when Teena works she earns $13.48 a month- all of which she keeps for her own expenses. This, in addition to a regular family allowance- $2.13 a week. Which she spends on movies, bus fares, cokes, school supplies, lunches, candy, etc.”

Through the persona of Teena, Ellis proved to affluent clients that teenagers had money to spend and that they were eager to do just that. As Ellis presented Teena to more advertisers, Teena was transformed into a more sellable ideal with her consumer potential emphasized and her less-commercial characteristics, such as intellect, downplayed. Regardless, Seventeen urged advertisers to take advantage of Teena’s lack of experience in knowing exactly how to spend money as a consumer. As Massoni notes, through Teena, Seventeen convinced advertisers that they could easily influence the “impressionable” audience of teenage girls to buy new products. The quiet creation of Teena, while unknown to the general public, became evident in the pages of Seventeen in subsequent months, where advertising slowly grew to eat away more and more pages of its content. By the end of Seventeen’s first year, advertising space took up 55% of each issue.

“You’re going to have to run this show- so the sooner you start thinking about it, the better.”

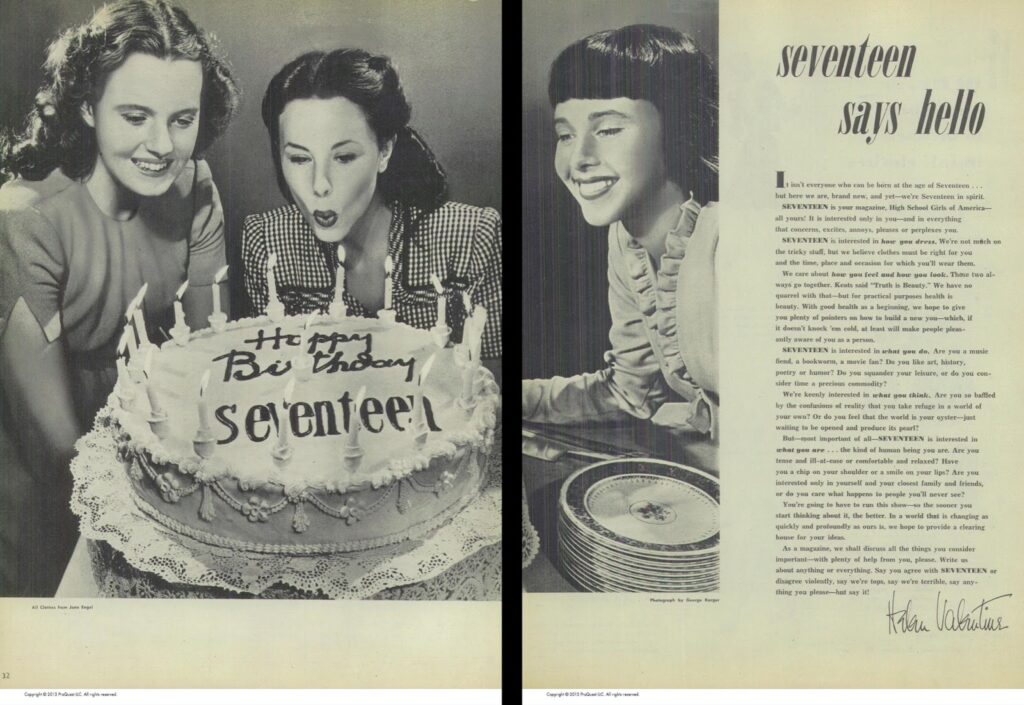

It takes reading only a few pages of the original September 1944 issue of Seventeen to see that, unlike Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar, the magazine unabashedly tries to forge emotional connections to teenage girls, and teenage girls exclusively. Themes of Seventeen’s first issue such as birthdays and celebrations are showcased on both the cover (which portrays a young girl with a clear, pale complexion holding up the numbers “1” and “7” in either hand while smiling at the camera) and a letter from Valentine, which is accompanied by a photo of three white, smiling models encircling a cake that reads “Happy Birthday Seventeen”. The positioning of the three models is symbolic of the way that Seventeen envisioned its relationship with its audience. Upon looking more closely at the photo, it becomes clear that the model positioned in the center of the photo is considerably older than the two girls standing on either side of her. She has hollowed, contoured cheeks and a more mature, angular face. She takes an active role in the photo, leaning forward to blow out the birthday candles while the two, younger girls standing on either side of the frame look down and smile. They look much closer to Seventeen’s targeted age group of adolescent girls. Their faces are chubbier and softer, and they have large cheeks and round faces, indicating that they have not yet reached adulthood. Valentine was the mature, merrymaking host, and the whole of America’s female youth was invited to the party.

In the accompanying letter of the first issue, entitled “Seventeen Says Hello”, Valentine makes her intent with Seventeen very clear to readers: “SEVENTEEN is your magazine, High School Girls of America- all yours! It is interested only in you- and in everything that concerns, excites, annoys, pleases or perplexes you!” Valentine notes that while Seventeen was interested in “how you dress”, “how you feel and how you look”, “what you do”, and “what you think” (all of which became different categories in Seventeen’s table of contents), they were most interested in “what you are”:

“Are you tense and ill-at-ease or comfortable and relaxed? Have you a chip on your shoulder or a smile on your lips? Are you interested only in yourself and your closest family and friends, or do you care what happens to people you’ll never see? You’re going to have to run this show- so the sooner you start thinking about it, the better. In a world that is changing as quickly and profoundly as ours is, we hope to provide a clearing house for your ideas.”

By way of this letter, Valentine pushed forth a somewhat modern-day declaration of rights and components of the teenage girl that she and her team wished to enforce in Seventeen, and promised teenage readers that she was committed to developing an intimate and psychological bond with them. The yield of this novel approach in publishing was monumental- all 400,000 copies the first issue of Seventeen sold out in six days. Three years later, copies of Seventeen reached one million, and by 1949, Seventeen declared that its readers comprised more than half of the population of American teenage girls. From its inception, the way that Seventeen engaged their teenage readers was as a trusted older figure, a guiding force, and as an influencer to be accepted and embraced by young women as they tried to figure out identities of their own. Valentine invited and welcomed teenage girls to embrace the magazine while simultaneously asking advertisers to trust and invest in Seventeen’s ability to mobilize teenage girls as powerful consumers.

The 1944 launch of Seventeen was a monumental catalyst in how teenage girls would come to be regarded and taken seriously by advertisers as an influential market, innocuous in its promise and threatening in its magnitude. The inception of Seventeen heralded the beginning of new and unchartered territory in the history of adolescence by revealing the potential of the teenage-girl market to advertisers, along with irreversibly expanding their impact in society as a whole. While in the pages of Seventeen, teenage girls were ultimately valued for their potential as consumers, they were also given attention, guidance, and support as they navigated the tumultuous, unpredictable, and confusing period of early adulthood. As Miriam Forman-Brunell notes, “Girls liked [Seventeen] because it tried to make them better teenagers rather than good little girls or elegant adults.” Seventeen steadfastly defined and presented what the American teenage girl was, who she could be, and how she could be influenced and guided through the world well into the 21st century.

While Hall was one of the first to formally define and categorize the teens’ psychological transition between childhood and adulthood, it was through their potential as a new consumer force that teenage girls were recognized and understood across wider American culture throughout the 1930s and 1940s. From advertisements by department stores like Lord & Taylor to junior sections in magazines like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, brands and retailers alike consistently failed to understand the emotional support and guidance that would support and attract teenage girls as new consumers trying to navigate the world. While other publications balked at grasping the full complexity, substance and power of teenage audiences, from its inception, Seventeen Magazine tapped into the restlessness and need for validation, guidance, and support that teenagers took on in establishing and exploring themselves en route adulthood. While Seventeen aimed to provide a space for the teenage girl to have a better sense of self and community, it also invited advertisers into such intimate and trusted spaces, which only furthered the growing instinct of teenagers to see their selfhood as attached to consumerism, now brought to life in magazine pages as a rite of passage for young readers.

“As a matter of course, young girls deserve attention, praise, and inspiration. But they also deserve freedom, support, and genuine compassion.”

In the end, Seventeen’s impact on female teenagers and consumer spending incrementally dwindled, until in 2013, it ceased publication. Strategies that the magazine employed, yet, remain omnipresent in the pages of its never-ending modern-day teen fashion and lifestyle-centric brainchildren. Today, there are some aspects of fashion magazines that empower, and other aspects of fashion magazines that exploit, the female teenage experience. The line between these two is very thin, and now more than ever, every reader must define for themself where it should be drawn. As a matter of course, young girls deserve attention, praise, and inspiration. But they also deserve freedom, support, and genuine compassion. Young girls deserve the autonomy to break out of any and all boxes manufactured around them by society, no matter how well-intentioned, including the idealized image of teenagerhood that Seventeen created for its readers, who, for many years, were depicted in print as overwhelmingly white and of European descent, whilst exclusively hailing from middle and upper-middle-class backgrounds. Both today and until further notice, the shadow of Seventeen lurks in the life of every American teenage girl, who, even now, still needs guidance and support in not only becoming a virtuous adult, but the best teenager she can be.

THIS PIECE WAS WRITTEN WITH THE HELP OF THE FOLLOWING WORKS:

Caulfield, Keith. “Olivia Rodrigo’s ‘Sour’ Debuts at No. 1 on Billboard 200 Albums Chart with 2021’s Biggest Week.” Billboard, 1 June 2021, https://www.billboard.com/pro/olivia-rodrigo-sour-billboard-200-debut-2021-biggest-week/.

Cooper, Kelly-Leigh. “Kylie Jenner: How the Reality Teen Founded a Cosmetics Empire.” BBC News, BBC, 12 July 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-44805888.

“Cover”. Harper’s Bazaar, September 1944.

“Cover”. Seventeen, September 1944.

Forman-Brunell, Miriam, ed. Girlhood in America: An Encyclopedia. The American Family. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2001.

Hall, G. Stanley. Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education, Vol. 1. New York: D Appleton & Company, 1904. https://doi.org/10.1037/14684-000.

“Junior Bazaar.” Harper’s Bazaar, September 1944.

Lord & Taylor. Advertisement, New York Times, October 4, 1934.

Malik, Farah. “CHAPTER SIXTEEN: Mediated Consumption and Fashionable Selves: Tween Girls, Fashion Magazines, and Shopping.” Counterpoints 245 (2005): 257–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42978704.

Massoni, Kelley. Fashioning Teenagers: A Cultural History of Seventeen Magazine. Walnut Creek, Calif: Left Coast Press, 2010.

Onion, Rebecca. “(French!) Kissing the Teen Mag Goodbye.” Slate, November 16, 2018. https://slate.com/human-interest/2018/11/seventeen-teen-mags-goodbye.html.

Oswald, Anjelica. “How Zendaya Went from a Disney Channel Star to a Blockbuster Darling.” Insider, September 1, 2021. https://www.insider.com/zendaya-career-evolution-disney-to-marvel-hollywood-2017-8.

Schrum, Kelly. Some Wore Bobby Sox: The Emergence of Teenage Girls’ Culture, 1920-1945. Girls’ History & Culture Book Series. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Silverman, Sylvia S. Clothing and Appearance: Their Psychological Implications for Teen-Age Girls. New York: Teachers College Bureau of Publications, 1945. https://doi.org/10.1037/11473-000.

Tenbarge, Kat, and Kieran Press-Reynolds. “Inside the Life of 17-Year-Old Charli D’Amelio, the Most Popular TikTok Star in the World Who Now Has Her Own TV Show and Clothing Line.” Insider, September 24, 2021, https://www.insider.com/charli-d-amelio-bio-how-old-tiktok-famous-renegade-super-bowl-2020.

Tiqqun (Collective), and Reines, Ariana. Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl, Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2012.

Valentine, Helen. “Seventeen Says Hello.” Seventeen, September 1944.

“Vogue’s Junior Fashions.” Vogue, September 1, 1944.

Ward, Tom. “Don’t Sleep On YouTube Star Emma Chamberlain.” Forbes. Accessed December 15, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tomward/2018/09/25/dont-sleep-on-emma-chamberlain/.

One reply on “The Obsolete Vision of Seventeen Magazine”

thank you Samuel <3