A Los Angeles artist wages existential warfare.

💀NOSTALGIA OR NECROPHILIA? PART II💀

THEO MERANZE

For pandemic-era college graduates—a category I’m in, for better or worse—foraging the nation’s city centers for uncertain futures (read: jobs) can feel overwhelming and intangible. So, like my fellow inheritors of a world on wounded legs, I tend to latch onto the things that draw me in digitally, and follow their scents. As you and I both already know, plunging the internet for valuable perspectives is incredibly challenging. If I were a socially disaffected twenty-something in 1967, I would probably be marauding through San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, smoking hand rolled cigarettes and talking about love, or maybe searching for truth in some CIA psy-op. Now, the median rent in Haight-Ashbury is $2,395, and the hippie generation extracts trusts from companies that attempt to employ transcendental meditation to increase productivity and elect CEOs on the basis of burning man acid trips. Thus, I was (and still am) stuck searching the internet, scrolling through bottomless valleys of nihilism and false prophets in hopes of finding a beacon of light. Spencer Longo, a Los Angeles-based Artist whose lucid work derives its power from such contradictions, is among the chosen few.

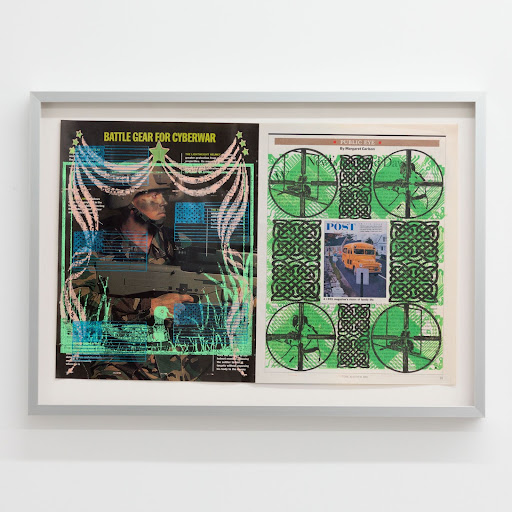

I initially encountered Spencer on Instagram, through an eye-catching page run by the online art(?) collective Do Not Research. According to their website, which is peppered with presumably-fake quotes from notable publications, they are a “detestable band of washed up millennial seapunks (Lolcow)” and a group of “zoomers obsessed with Mark Fisher (Buzzfeed).” Theirs is the sort of online space that thrives behind an ephemeral, pointedly absurd, and disorganized collage of interests. Posts range from Spencer’s own work (In 2022, Spencer published his most recent collection of work, titled TIME: a book-length collection of striking political collages, with the New York based imprint Inpatient Press. The collection also was presented physically at the King’s Leap Gallery in New York City), cultural criticism, and, as of the writing of this piece, one of my favorites: a video of automated cursors doing the cha-cha- slide. I would come to learn from Spencer that it was the brainchild of his friend, visual artist and internet cultural researcher Joshua Citarella, one of his peers from a mid 2010s post-internet cohort. In retrospect, it seems fair to say they were ahead of their time in many ways—investigating the chaos of internet politics, cultural disintegration, and paranoid American extremism far before 2016 or 2020.

In the wake of existential dread and social isolation, by the time I began following Do Not Research, I found increasing solace in the artistic and political communities that I encountered on the internet. Such online soul searching was a common experience among my early twenties peers—one that mirrors the politically-charged experience of “graduating into the 2008 financial crisis” Longo’s generation has in common. And while the world did in fact begin to open itself up again, this new way of relating to others—my increasing addiction to my phone—maintained itself. Despite being faced with the potential for an active, embodied life, I found myself deciding that I’d rather be online, ingesting regurgitated materials of the past.

The past’s never-ending slew of visual artifacts are becoming progressively unavoidable. The tension between them and our chaotic present continues to define our era’s political discourse, whether that be in the form of memes, instagram infographics, documentaries, or perhaps most terrifyingly, deepfakes. Symbols are, for better or worse, more important than ever, but also more manipulatable than ever. Attempting to understand this dynamic is among the things that make me relate to Spencer. He derives his ethos from within the chaos.

You would never admit this to anybody, but you are, in many ways, deathly bored of it all.

Spencer invited me to his fashion district studio on a characteristically dry afternoon in Los Angeles. The fashion district is an at-times chaotic cluster of storefronts and tenements adjacent to Downtown LA. It’s a mysterious place, where random men appear miraculously from colorful stucco alleyways and attempt to direct you down one way streets. A romantic might say that it is this subtly whimsical atmosphere that has led it to become one of the hubs for art-related happenings in L.A., but for sake of honesty, it’s more than likely the cheap cost of space in the district.

Los Angeles is a fitting hub for Spencer’s most recent work. If it is true that, as Joan Didion said, “Los Angeles weather is the weather of catastrophe,” and (prophetically) in the wake of the Watts riots, that “the city burning is Los Angeles’s deepest image of itself,” it makes sense that art with front row seats to the theater of the apocalypse is created in its bowels.

🚨THE SIREN SONG OF THE APOCALYPSE🚨

It is 2064. You are seventy years old and three years away from hopefully being able to retire. Sitting in your office, you go to get your morning coffee and see CNN announce that another segment of Florida has been overtaken by the ocean. This is bad, the anchor says, because congress isn’t sure what to do with even more refugees. Your shift ends in seven hours, and your head hurts. The doctors tell you that your migraines are the product of decades of screen usage, but your job requires eight hours of screen time a day. Less so because eight hours is the time required of you to complete your work, which if you, or your manager, were honest with yourselves, could probably be done in two hours, but more so out of the need to distract yourself from the boredom of an eight hour workday. Relatedly, remote work, a now politically-charged practice, has been disallowed in your office in order to “foster community.” As the 9 AM smoke-filled violet summer-sun-rays begin to sink onto the disheveled carpet floors, all you can think of is getting home to sleep, but not to rest. That would require a level of freedom that is not available to you at the moment. You would never admit this to anybody, but you are, in many ways, deathly bored of it all.

This likely future, one in which collapse is a slow, destructive, and soul crushing process that may take up lifetimes (your children will likely be alive to witness Florida go under, but you probably won’t) seems incompatible with the way in which many in our society process destruction. The slow burn is, after all, much more disturbing. We seem to be predisposed to a biblical notion of catastrophe as rapture— of apocalypse as pseudo- entertainment: hell-fire, extravagant destruction, fast-moving societal collapse where only the strongest and most prepared will survive, or in the case of the contemporary media-sphere (Fox, CNN, etc): they are coming to get you, and they will stop at nothing before your way of life is destroyed.

This discourse is unrealistic and best suited for major-budget films. It also ignores the reality understood by those already deeply affected by the violence of the present: the reality that history, with all its turmoil, oppression and bloodshed, has and continues to be an ongoing apocalypse. Such a fantasy, like most delusions, serves a pivotal function for the psyches it inhabits. It is an escapist dream which pervades and preserves the violence of our zeitgeist, one which Spencer views as easily manipulatable and a breeding ground for “grifting and scams.”

THEO MERANZE: I’m curious about how you found this community of people interested in an experimental, internet-centric mode of art so early on in your career.

Spencer Longo: The beginning of it for me was definitely stuff on Tumblr. There was this group-project called “poster company” where people would do totally digital abstract-impressionist, Photoshop-centric stuff. From there I began to find more people making art on the internet—Facebook, actually, was also quite a big part of it. It’s kind of funny looking back on how productive Facebook actually was. If you did a show, you could put albums of work online, there was no limit, and you could caption them, et cetera. It was a really good social network early on for following people’s work and eventually seeing their shows in person. There was also a website called JstChillin which had people like Brad (Troemel) and the filmmaker Eugene Kotlyarenko. It was really this kind of social element where I wanted to see work that felt reflective of the internet.

So when did you move out here to Los Angeles?

I moved out here at the end of 2010. I finished undergrad in 2008 and spent the next two years making work in my home studio. During that time I also started corresponding with a record label based out here called Not-Not Fun. I just randomly sent them some collage work and they wrote back saying that they loved it and wanted to work with me. I was also making zines at the time and I would just mail them to random people I thought were cool, and through that I met this guy who was out in LA who made video art, so just the combination of all these things led me to come out here. When I got to LA I can remember this series of events called B.Y.O.B., which stood for “bring your own beamer” — like a projector. People would essentially get a space, make a bunch of work that could be projected on to the walls, and hang out. That was kind of what got me into the internet scene that was going on at the time—going there and introducing myself to people, et cetera. Eventually, around 2011-2012 was when I started collaborating with this Jogging group that Josh (Citarella) was a part of.

(Jogging, according to an artist statement found on their tumblr, was a “context-driven art project consisting of 15 team members based in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Oslo.”)

Jogging was kind of an attempt to push the idea of the documentation of work being the end goal of work to its extreme form, like, “you don’t even need a gallery to put things out there.” A Lot of the work itself would be these assemblage pieces that would only exist in the art world as photographs. The pieces would be these kind of visual puns. For example, I took a wide brim Nike hat and filled it to the brim with pomegranate seeds. A lot of the work revolved around health identity politics of the time. I did that for two or so years before the collective ended.

I’ve always found myself attracted to collaborative, collective oriented work. I think I really sought that out and found a lot of value in it, and Jogging went against a lot of ideas about ‘the artist’ which never really resonated with me, the hyper-individualist, cult-of-the-self stuff. Also, when you don’t have a studio and you’re making work by yourself in your room, you know, it makes more sense to do it digitally. After Jogging I found myself more & more integrated into this world that started as an internet oriented, but not about keeping it on the internet kind of thing. Around 2015 I had a pretty significant shift in my artistic practice, getting access to a studio at the time, but I still maintained a lot of the ties to the world I was really invested in early on.

Given the artistic and intellectual world you inhabit, I wonder how much of an effect Trump’s election in 2016 had on your personal and artistic outlook.

It was kind of like, if you were invested in online subculture prior to that, like with gamergate, you could have seen it coming from a mile away. Even further back, you know, a period that I really lock into interest-wise would be 1979 to 1999, where you had all of these people with “apocalyptic visions” and militia movements. We tend to forget how crazy that really all was. With my work I want to engage with this longer vision of American psychosis and Paranoia.

I noticed in your work a focus on catastrophe and collapse—a lot of these pieces have a kind of apocalyptic hue. How do you see the notion of the apocalypse and apocalypse narratives fitting into your art?

I was actually interested in the book of Revelation during a lot of the TIME work. The notion of catastrophe and collapse is such a powerful narrative driver for a lot of the movements I’m interested in, you know, preppers, extremists, cults etc. This is why I find cult structures to be so fascinating. I was around eight when Heaven’s Gate happened, but it had an important effect on me. Cults are always structured around a collapse event. They’re grifts, you know, structured like pyramid schemes.

Did the pandemic affect your perspective? I encountered your work in a post-pandemic context, and for me, personally, it reminded me deeply of that moment and its social chaos. It feels like that period of time is one of the causes of people my age having a resurgence of interest in everything you’ve been a part of.

The Pandemic didn’t effect my work, or the way that I work, personally. Hearing you talk about it, maybe it’s that it just kind of proved any underlying thesis. It was like all of the conspiratorial stew got gas poured on it.

One thing that I really appreciate about your work is that while it is very intellectually inclined, it doesn’t define itself with theories or dogmatic ideas. It seems to come from a similar place that theory itself actually comes from, it’s very lucid. Would you agree?

Yes, it’s very of the world. Whenever I make something, I can tell that it’s clicking when there’s an interaction between the formal and conceptual element. It’s not about coming to a thesis point necessarily. I’d rather lean into the inherent elements of art that are more sublime or existential—I wouldn’t want to make art in a way that would be better served for writing. The way I’d put it is that I have things that I think about when I’m making it, but that really don’t matter for the viewer. I really want my work to resonate with people of all different types of backgrounds, and I want it to feel as if it’s inviting reflection. I often think about it like this: there’s work that points outward and work that points inward. Work that points outward tells you what it’s about; it arrives at the gallery pre-cooked. Work that points inward has a void within it that requires a viewer/s to complete it; it’s more open. This is more where I place my work. I’m Interested in when people have completely different associations, like when I put two things together and they have completely different ideas about what it means, it’s all incredibly valid to me.

How did you approach the process of making work for TIME?

It was in many ways a chance operation kind of thing. Not that it needs to be interpreted in this way, but I would take apart these Time magazines and find these juxtapositions that were almost like jokes: two things across from each other that were almost funny or in tension with one another. Then the images, the visual elements, would be the sub-conscious connections underneath the tension between the two things. So, in the case of the Boy Scout piece, by having the question gay boy scouts juxtaposed with stem cell stuff, it gets into anxieties about biology, religion, culture, etc. The reason why I chose to use extremist images in some of the work is that I was trying to show that anybody can potentially be motivated by the basic human drives and emotions they attempt to speak to. This isn’t to say that they aren’t at times destructive, but to sympathetically contextualize them.

We’re living through a time where popular intellectualism and general critical discourse has become fraught and stagnant. It seems as if we haven’t found a lot of successful, healthy ways to position ourselves within such a context. Anybody can have a podcast or self-publish their work, yet it seems like new, productive ideas and movements are becoming harder and harder to come by. What I find so intriguing about your work is that it seems as if you traverse this context well through a kind of healthy skepticism. Could you elaborate on that?

Anybody being able to have a podcast isn’t inherently bad, but it means that the way to get popular is being loud and contrarian, which is why I think we’re in such an era of grifting. The structures at play inherently lead one towards that. The promise of the early Internet was to democratize, but in high school, I found that websites like Something Awful, which embodied an anti-utopian version of the internet, spaces that said “the internet sucks and is a parallel version of all the terrible things happening in the real word,” really clicked with me. I’ve told people this anecdote before, but the two things related to this that my dad really instilled in me were, without using the term, explaining to me what planned obsolescence in regards to technology was— I remember him saying “this thing is gonna be outdated in a year, and that’s an intentional aspect of what you’re buying,” and I also remember him buying a polo shirt and not realizing that there was a little polo logo on it and being like “I’m gonna return this, I don’t want to give free advertising for something I just bought.” I think that those two things made me very critical of tech and consumer culture. They had a profound effect on me.

One reply on “Spencer Longo and the Siren Song of the Apocalypse”

Spencer’s work has always compelled the audience’s attention. It communicates so much information. Sometimes with humor, sometimes it is disturbing, always engaging and enlightening.