A sonic chemist digs through new crates.

🍄CAN’T YOU SEE?🍄

SAMUEL HYLAND

A little over a decade ago, when the then-prodigal teenage rap phenom Earl Sweatshirt made his long-awaited return from a youth development camp in Samoa, he marked the occasion with a brief, synth-blitzkrieg loosie track sparingly titled “Home.” “Thanks James,” he said slyly in a boastful denouement, sampled cymbal crashes threatening to overpower his sophomoric quippage. “Aaaaand I’m… back.” The “James” in question was James Pants, an eclectic Stones Throw signee whose modest-yet-sprawling practice had earned the admiration of several Odd Future members — including raucous ringleader Tyler, the Creator, who called him “one of the most creative fucking people to walk this earth,” and the young-and-promising Sweatshirt, who co-opted his “(first name) (article of clothing)” framework for his own fabled pseudonym. The sample for “Home,” and the thing Earl was thanking him for, was “Theme from Paris,” a frenzied instrumental track from Pants’ 2008 breakout LP Welcome. In similar spirit to the album at-large, the song’s appeal banks more on erratic quirks than palatable consistencies. In its opening, pompous synthesizers blare the sort of chord progression a clown might ride a tricycle to; within forty seconds, there’s a hectic drum solo that sounds half jazz fusion B-side, half early-aughts punk rock demo tape.

“We’re worried that stuff’s not going the way it’s supposed to go, but there is no way it’s supposed to go. Exactly how it goes is how it’s supposed to go.”

Oddball elements, and the audacity to fuse them together, are integral to Pants’ strange allure: where other musicians are more likely to insert themselves, he instead relinquishes center-stage to peculiar ingredients, tip-toeing around the spotlight like a witch might tiptoe around a cauldron. In Seven Seals, Welcome’s roving 2009 follow-up, a three-track opening spree sees him go from Catholic-sounding Jim Morrison, to breezy romanticist, to ominous, perhaps furious, ghoul. The latter ballad begins with a deceivingly-placid flute intro, only to violently interrupt any hope for peace with angsty key-smashing and ultra-aggressive drumming. “I’m… beyond… beyond time,” Pants whispers amidst the chaos, both sinister and barely audible. “Can’t you see?” You can’t, and for some reason, it’s exactly this that makes his music worth coming back to — the punchline is always changing, and every time Pants’ disembodied voice asks whether you get it, you must first dig through layers of disparate ephemera before you find wherever he may be hiding.

Today, thirty-ish minutes after 2 PM on a March Sunday afternoon, that hiding place happens to be a sunlit family home in West Orange, New Jersey — and luckily for me, there isn’t much weird sonic ephemera to be sifted through in order to find it. Born James Singleton, Pants is a family man now, which means the ephemera, though still there, looks slightly different. A day before our interview, he tweeted a heartbreaking image of a broken pickle jar, contents sprawled across a crime scene of bubbly green juice. “One frustrating thing about earth’s gravity is when you spill all your pickles,” he deadpanned to his followers. The pickles were spilled by one of his two daughters in a rush of pre-snack overexcitement; nearly 24 hours later, the house still smells ever-so-faintly like cucumbers and vinegar: a tough odor to get rid of completely, and a different kind of erratic quirk from the musical ones he’s long curated. “In all honesty, man, I’m not an interesting person,” he says, matter-of-factly. He’s sporting a burgundy crewneck and a denim baseball cap bearing a fox on its front, the sort of outfit you might find peppering the bleachers of little-league games. “I’m just a completely regular person. Or maybe that’s not true. But nothing exciting— we have a dog, I go jogging a lot with the dog, and then I sit on the computer most of the day. Then it’s another dog-walk or jog at night, hang out with the family, do some reading, listen to some records, then repeat.”

“Anything you look at in life is super interesting. Whether it’s paint on a wall, or electricity, or blankets, or whatever. It’s fascinating.”

This modest outlook, which trades self-centering for scatterbrained adventure-hunting, is a line that threads Singleton’s artistic dynamism to his lifelong approach. One book he’s been reading lately is Star Maker, a 1937 science-fiction novel by the British philosopher Olaf Stapledon. In it, an English narrator is transported, by unexplained means, outside of his body and into a weirdly existential choose-your-own adventure journey through the history of trans-cosmic sentience. The titular “Star Maker” is the creator of the universe, and strangely, when the two meet, the grand mastermind’s relationship to its handiwork comes across a lot like a creative’s relationship to a fleeting project. “It seemed to me that he gazed down on me from the height of his divinity with the aloof though passionate attention of an artist judging his finished work,” Stapleton’s unnamed narrator reports, “calmly rejoicing in its achievement, but recognizing at last the irrevocable flaws in its initial conception, and already lusting for fresh creation.” James Pants’ creative output borrows from a similar modus operandi: there’s too much to be discovered to dwell on past discoveries — no matter how comfortable those past discoveries may have been, nor how uncomfortable moving beyond them may end up being.

Over the past several years, the most lofty previous discovery he’s learned to move on from is his once-prolific musical project. Between relentless touring necessities, demanding studio requirements, and the miscellaneous busywork that threads it all together, taking a step back is, perhaps, a sensible option for a man with a wife and two kids to take care of. But it’s also a necessary eschewment of a familiar trap. Garnering label-backed acclaim the way Singleton did a decade ago, as opposed to making music for no one in particular, means suddenly having a hefty bunch of people to keep entertained — first for money, and second, if at all, for fun. “I was a D-List artist at max,” he laughs, “but I was very happy with what I was doing. But once you do something and people start catching on, it becomes a thing of Oh, I’ve got to do that again. There’s this pressure, and over time you start critiquing your stuff before it’s even out. Which I think is deadly.” The most recent album he released as James Pants came out eight years ago, in 2015; it featured a tightly-packed 22 minutes of minimalist soundscapes and odd non-sequiturs. (Something else was recently in the works, but when it felt like it wasn’t going anywhere, he opted to give it to Lil B.)

Slightly less deadly — at least under certain circumstances — than creative self-suppression is hunting for wild mushrooms. It’s mid-March, which means that at least here in New Jersey, the time of year is dawning for fungus fanatics to take to the forests, mushroom identification guidebooks in hand, and scavenge for whatever rare toadstools may be hiding in plain sight. Singleton has been invested in the strange world of mycology since the pandemic, when a co-worker who had been talking about it for years finally convinced him to give it a go. “I just started noticing them everywhere. I got much more into hiking, and started snapping photos of mushrooms,” he reports. “Then, it became Let me see if I can identify these. I bought a couple of guidebooks, then it just kind of ballooned. I went a little bit off the deep end, and started building this mushroom library. I have a bookshelf full of mushroom ID books. I bought a microscope. I joined the New Jersey Mycological society, and the New York mycological society — which was founded by John Cage, by the way — and started visiting forums and joining online lectures.” He concludes his spiel by offering a comparison: “It’s a lot like record-hunting.”

And especially for someone like Singleton, who prizes foraged unknowns over low-hanging fruit, it is. A few years ago, he learned that he had a mild variation of Asperger’s syndrome, a condition that often manifests in abnormal levels of dedication to hyper-specific topics. Though his career-long “crate-digger” label has clear musical implications, much like his creative footprint, it’s much better applied across a broader scale than to a focused point. “I guess I’m more on a Daoist wavelength, really,” he says, upon being asked where he is existentially. “Anything you look at in life is super interesting. Whether it’s paint on a wall, or electricity, or blankets, or whatever. It’s fascinating. So when you suddenly realize that — good or bad — everything is interesting… I think we ask the wrong questions. We’re worried that stuff’s not going the way it’s supposed to go, but there is no way it’s supposed to go. Exactly how it goes is how it’s supposed to go.”

Though perhaps inadvertently, it’s a fitting explanation for the disjunctive qualities of his music. In a neutral 2008 Pitchfork review of Welcome — which called the album “not good, but not awful” — writer Nate Patrin seemed to grapple between dismissing it for its weirdness and giving it credit for its charm. “I can’t unreservedly call this album good– yet– but I can definitely recommend that you listen to it,” he concluded, “because there’s not much out there that really sounds like it, and for every moment where you think its sheer whacked-out sloppiness is going to give you a headache, it delivers a flash or two of giddy brilliance.” As odd as it’s alluring, the appeal of Pants’ work is not one or the other, but the fact that the two polar opposites can coexist: strange ingredients boiling in a stranger cauldron, all the while their mastermind ditches the spotlight for whatever odd discovery is next.

🦠🦠🦠

“What more do you want?”

James Singleton was born to a family of devout Presbytarians in Spokane, Washington, a scenic suburb where thrift stores brimmed with rare instruments and pickup trucks shared open roads with shotguns. He moved around a lot, and by his freshman year of college, had already been involved in a smattering of odd musical startups; they included a Texas-based Black Nationalist hip-hop collective that he DJed for, and a short-lived half-satirical, half-serious math rock faction. What Spokane boasted in peculiar singularities, paradoxically, it lacked in opportunities to go beyond them — a catch-22 that meant ideal creative environments often came under the condition of being trapped within their boundaries. A few days after our interview, underneath violent wind gusts bordering NYU’s campus, I met with two art-adjacent visitors from Washington State. “I think everybody that’s there is in the midst of leaving,” one said. “I love it there, but we’re all trying to make it out.”

Much of Singleton’s musical practice, in those early years, hinged on distilling his growing tastes into specific, targeted sounds. Long afternoons were spent in nearby record stores, where he combed through sprawling catalogs of disparate, trans-genre touchstones to find reference material for both his own work and instrumentals for his friends. Around this time, he had just heard of Stones Throw Records, a young hip-hop label founded by California DJ-slash-producer Peanut Butter Wolf. “I bought Peanut Butter Wolf’s album, My Vinyl Weighs a Ton,” he says, “and I immediately became a fan.” Later that year, Wolf would play a rave in Austin, Texas, where a high-school Singleton happened to briefly be living with his parents. He did some guesswork to come up with his email — the internet was a few years old at this point, which made it a far easier feat than it would have been today — and reached out on a whim with an offer to take him record shopping. They agreed to meet after his show, which fell on the night of Singleton’s prom; over the next couple of days, the two drove aimlessly around Austin’s record stores, exchanging recommendations and marking common tastes.

Singleton would get his opportunity to move out a few summers later, when, after years spent keeping in touch with Wolf, he was invited to intern at Stones Throw’s Los Angeles office — an opportunity he hoped would ultimately lead, in some fashion, to being signed. Reality was a bit more underwhelming: he was a terrible intern (his own words), and returned to Spokane dejectedly to work in a nearby grocery store and go back to making strange music for fun. Oddly enough, though, it was only within that period, years later, that he began fielding calls from the label to first record cover songs for re-release… followed by eccentric one-offs to be sold exclusively at nearby hot-dog carts… followed by, finally, his own debut album as an official Stones Throw signee — to be released originally under his name and sold in real stores.

Something that marked Singleton’s appeal was that, especially for a label that made its name on guarantees for quality hip-hop relics, his music fused together unknowns in a way as refreshing as it may have been maddening. “I don’t think I’m a good musician at all,” he says. “I’m just good at combining things.” For Welcome, the first LP he’d release under the label’s banner, the things he sought to combine came in the form of three particular Garys who had been in heavy rotation: Gary Wilson, his eccentric Stones Throw label-mate, Gary Davis, the virtuosic folk pioneer, and Gary Numan, the controversial electronic music contrarian. A cumbersome set of over 40 demo songs were condensed into 16 tracks Peanut Butter Wolf liked best; the result was a record that sounded sleazy in some places and desperate in others, endearing directionlessness threading together its roving list of elements. In its final track, the anguish-strained voice of what sounds like an old man rages through a host of brief, profane outbursts, all soundtracked by a more somber version of the clown-tricycle synth music the album began with. “You son of a bitch… agh!” it yelps in frustration, seemingly ready to burst into furious tears at any given moment. “What more do you want?”

“It’s all really cool. But if you brought it down to the most primitive… primitive… caveman-like level — no fills, no frills, no flourishes, just the brutal intensity of rhythm — then I think that would blow everybody’s socks off.”

Post-music, Singleton’s answer to that has been getting his creative rocks off in other mediums. For the past several years, he’s been working at the business media conglomerate Bloomberg in its Manhattan headquarters, where he collaborates with journalists to develop tools for interactive web articles. One particular project he cites as a favorite is 2018’s “American Mall,” a quirky 8-bit minigame that tasked Bloomberg visitors with fielding the many troubling corporate hoops and ladders a U.S. mall owner might be faced with on a weekly basis. “DECADES OF OVERBUILDING AND THE INVENTION OF ONLINE SHOPPING COMBINED TO LEAVE THE COUNTRY WITH AN EXTREME EXCESS: THE U.S. HAS FIVE TIMES MORE RETAIL SPACE PER CAPITA FROM THE RETAIL-ABUNDANT U.K.,” an ominous title card reads in its opening screen, obnoxiously-parodic 80s synth music blaring through suspenseful chords in the background. “RETAIL EXPERTS EXPECT HUNDREDS OF AMERICAN MALLS TO CLOSE IN COMING YEARS. BUT MALLS DIE SLOWLY, AND THEIR SURVIVAL OFTEN DEPENDS ON THEIR OWNERS MAKING BRUTALLY DIFFICULT DECISIONS WITH FEW CLEAR UPSIDES. SEE HOW YOU FARE IN MANAGING THE DECLINE OF AN AMERICAN MALL.”

Playing the game, as I did for less than five minutes before growing frustrated, wastes little time proving to be a road studded with tough choices. Split between music, family, and a new career, Singleton’s path to Bloomberg followed similar ebbs and flows. By 2009, when he had his first child with his wife, his primary source of income was touring, which required him to be away from home six months per year. Upon deciding that a stable job might make more sense, he moved his family to Berlin to take on a role at the Red Bull Music Academy, where he helped to revamp the publication’s outdated website and code immersive longform pieces. (“I won’t say I’m good,” he said of his musicianship in a 2009 lecture there — not far removed from his current take. “I play mainly old stuff, so there’s always that challenge when you are in a club environment and people are playing dubstep and whatnot, with massive bass, and here you come with a Sergio Mendes song, girls kind of scowl.”) Six years later, in 2015, he saw a job posting on the Twitter profile of Bloomberg designer Steph Davidson. He applied on a whim from Germany, and within half a calendar year, was headed back to the U.S with his family as the publication’s newest software developer. “That’s really all software is,” he says, referencing the “American Mall” game. “Every day, something goes wrong. There’s a lot of hoops to jump through. It’s slightly masochistic. But it’s also slightly fun.”

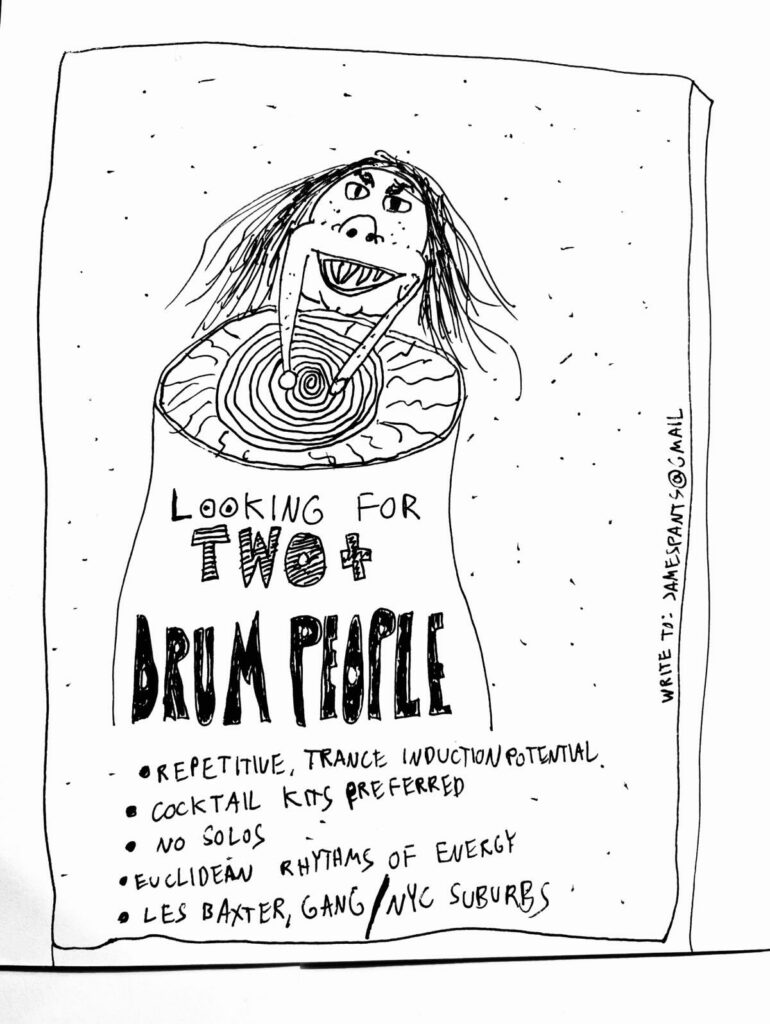

And so is music — at least when it isn’t coming from the wrong place. These days, Singleton is done making music for any reason besides satisfying his own roving curiosities. First on that list of curiosities at the moment is an all-percussion band. “A polyrhythmic never-ending drum thing is what I have in mind, but I just haven’t met the right drummers yet,” he says. “Something along those lines, in my opinion, would be the only thing that can kind of cut through the noise at the moment. There’s just so much coming out. A lot of interesting, novel types of music. 100 Gecs and all this stuff… It’s all really cool. But if you brought it down to the most primitive… primitive… caveman-like level — no fills, no frills, no flourishes, just the brutal intensity of rhythm — then I think that would blow everybody’s socks off.”

Before he gets the chance to blow your socks off himself, if you feel so inclined to take it, an opportunity exists for you to do so on your own time. Last spring, Singleton tweeted a link to an in-progress euclidean rhythm generator he had been working on over the past several months. The barebones interface features two pie-chart drum machines (with the option to add more), each bearing adjustable settings for slices, volume, midi note, machine (MINIPOPS, TR727) and instrument (CABASA, HI BONGO, LOW BONGO, HAT_CLOSED, HAT_OPEN, etcetera). When I first gave it a try, I came up with — or, more accurately, stumbled into — something that sounded half like a Lil B Myspace loosie, and half like a fireable offense in Sun Ra’s Arkestra. As I write this sentence, the tab is still open on my laptop, its weeks-old creation enclosed and set to be revisited at the push of a button. “A simple euclidean rhythm generator,” the page’s minimal “about” tab reads. “More stuff coming soon.” Perhaps it’s true: sometimes, strange discoveries do lead to stranger ones. But graduating onto the newer eccentricities means ditching old spotlights. I should probably close that tab.

One reply on “Musical Mycology: Beyond Time with James Pants”

reading this made my tea taste better