Beneath the bright lights, a murderous underbelly awaits new prisoners.

SAMUEL HYLAND

The Queens-bound E Train I rode to my first day of tenth grade reeked of yesterday’s urine and today’s sweat — a familiar MTA concoction on its own, but a different beast when you’re delayed, stranded underground without internet, and left with few options but to either inhale the fumes or make awkward eye contact with its producers.

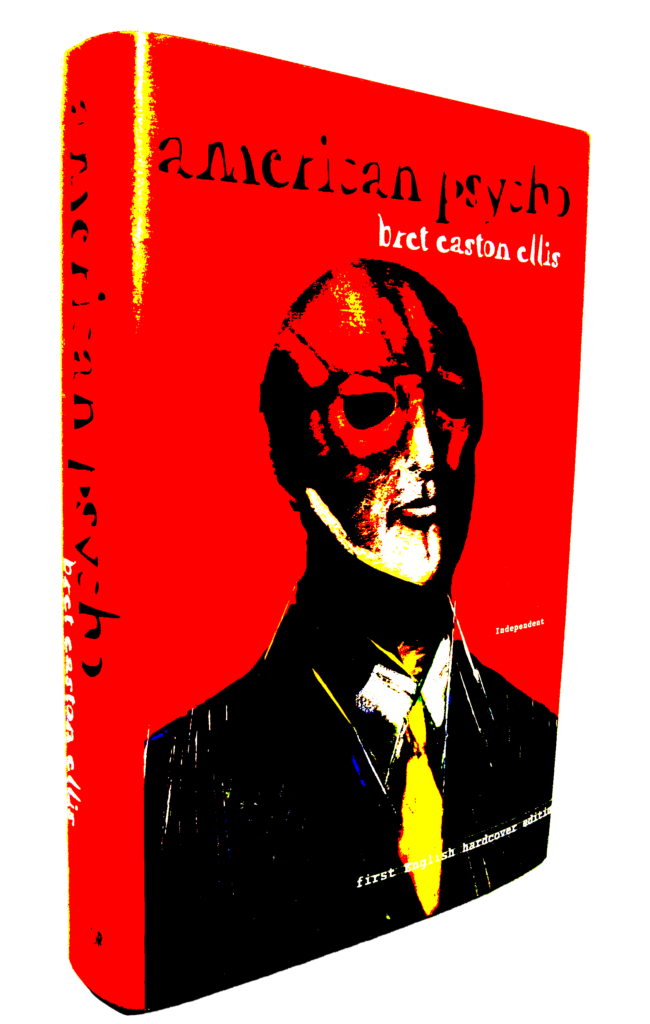

When wifi-free mobile games grew stale, and the familiar cyborg intercom’s apocalyptic PA ramblings (The New York City Police Department would like to remind you to keep your belongings in sight and stay aware of your surroundings… The New York City Police Department would like to remind you that backpacks and other large containers are subject to random search by the police… The New York City Police Department would like to remind you that it wishes death upon you and your loved ones…) bordered psychological torture, out from my freshly-purchased Jansport backpack emerged a book that had little business emerging from any high school student’s freshly-purchased Jansport backpack. Knowing this, straphangers in business-casual shot concerned glances that loosely followed a familiar pattern: land on the book’s cover, ease up to my eyes, dart back to the cover with a vengeance, squint back at my eyes as if to ask a question. “If you see something suspicious in the station or on the train, tell a police officer or an MTA employee,” the apocalyptic cyborg voice suggested, drily, over the speaker system. It never does tell you what to do when the suspicious thing is you.

“But just as looming, and perhaps a bit more difficult to admit, lay another congruent feeling — the only way to understand this murderous and unthinkable thing, it seemed, was to be murdered by it.”

Judgmental eyeballs are a fact of New York City’s streets (and subway cars), but the title in question has odd abilities to either make those eyeballs murderous, or make one markedly better, voluntarily or involunarily, at noticing them. When, 48 hours prior to my trip, I borrowed a tattered copy from the New York Public Library’s Muhlenberg branch — a grimy 23rd Street offshoot of NYPL’s better-known Bryant Park location, complete with witchlike librarians and the faint hum of languid one-on-one tutoring sessions — the woman at the desk glowered at me with a groany sigh, and I couldn’t tell whether it was because the book struck a nerve, or because it was a few minutes after 5 PM, and the library technically should have been closed. Hanging by a thread above the door leading out to 23rd Street’s familiar stench was a flickering, blood-red sign that wearily declared “EXIT.” Text in hand, treading beneath it felt a lot more like I was entering something much less familiar, and much more rotten.

At several dizzying points in Babyfather’s 2016 landmark LP ‘BBF’ Hosted by DJ Escrow, a disembodied cockney accent repeatedly asserts, with unsettling stoicism, the declaration “This makes me proud to be British.” In the album’s opening track, there is no music nor sound, save for the voice droning its patriotic claim over and over again for five minutes straight — a dare, of sorts, that demands a listener to firmly decide between laughing at its weirdness, or taking it as an artistic statement. In a cultural sense, inundation tends to operate on a similar two-pronged serious-or-not model: when with every new seasonal capsule drop, Supreme plasters its logo onto a brick, a fire extinguisher, or a helicopter, there are some who find it funny, and others who make withdrawals. But in the opening section of Bret Easton Ellis’s deranged cult classic American Psycho, which shamelessly drenches its narrative in name-drops, banal Wall-Street banter, and grimy New York City portraiture, a certain hilarious morbidity stands to make the two sides somewhat cancel themselves out. We meet titular American psycho Patrick Bateman in the back seat of a cramped yellow taxi in rush-hour traffic, and the first thing he ever tells us is a run-on sentence that screams This makes me proud to be a New York snob the same way Babyfather screams This makes me proud to be British:

ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER HERE is scrawled in blood red lettering on the side of the Chemical Bank near the corner of Eleventh and First and is in print large enough to be seen from the backseat of the cab as it lurches forward in the traffic leaving Wall Street and just as Timothy Price notices the words a bus pulls up, the advertisement for Les Misérables on its side blocking his view, but Price who is with Pierce & Pierce and twenty-six doesn’t seem to care because he tells the driver he will give him five dollars to turn up the radio, “Be My Baby” on WYNN, and the driver, black, not American, does so.

“The price for understanding is no longer being alive to understand, and it’s a price many are willing to pay.”

Months ago, in a controversial Intelligencer hit-piece on once-President Donald Trump and his quest for re-election, Washington correspondent Olivia Nuzzi embarked on a similar run-on sentence, much to the chagrin of Twitter’s legacy-blue-check journalism cool-kids-club: “On the day he announced his candidacy this past November,” she wrote of the scene at Mar-a-Lago, “the air was heavy with oleander and snipped greenery and sea mist colliding with mold and wood polish and hotel soap and the metallic vapor of Diet Coke and the alcoholic ferment of generations of cougars in Chanel No. 5.” Much like Ellis’ dizzying spiel, Nuzzi’s, too, served to introduce a sector of a much larger text — albeit less by luring readers in, and more by asking how much they might be willing to take. Trump, Bateman and Babyfather’s respective convoluted lores each center around regional cues, and perhaps regionalism, by and large, is what made me leap as eagerly as I did at the book’s up-front ethos. By my sophomore year of high school, New York’s twisted infrastructure remained in equal parts quotidian and enigmatic. The previous summer, when my dad forced me to visit NYPL’s Bryant Park location on a daily basis to study for an August regents exam retake, I instead used my trips to aimlessly sightsee on hours-long walks through Midtown’s gum-covered sidewalks, stupidly hoping that exposure to more New York City real-estate would make me more of a “real” New Yorker. From open roads bustling with throngs of tourists and free samples, to shady backstreets soundtracked by jangling coin-cups and drunken profanities, there arose a looming sense, then, that beneath the city’s glamorous ethos lay something murderous and unthinkable. But just as looming, and perhaps a bit more difficult to admit, lay another congruent feeling — the only way to understand this murderous and unthinkable thing, it seemed, was to be murdered by it.

Patrick Bateman’s lore hinges on the spectacle of this unknown: he, for one, absolutely has been murdered by it, and it has turned him into a murderer. A glimpse into his fucked-up echochamber makes it painfully apparent that uncovering New York’s underbelly can never be worthwhile, not only because it can chew up a saint and spit out a psycho, but also because it can stop mattering at the very moment it stops being an asymptote. The disturbingly masterful thing about American Psycho, though, is that Bateman’s insanity, much like New York’s own, serves to entice just as much, if not more, than it serves to deflect. Many of his stream-of-consciousness monologues center around snobbish self-glamorizations or snobbish critiques: his designer products and rigorously well-kept body; others’ less-cool designer products, their oh-so-choppable heads. “I’m tense,” he relays at one point, “my hair is slicked back, Wayfarers on, my skull is aching, I have a cigar—unlit—clenched between my teeth, am wearing a black Armani suit, a white cotton Armani shirt and a silk tie, also by Armani.” The GQ-ready rundown comes as he enters a dry-cleaning storefront to pick up a set of his blood-stained bedsheets — the source of his tension, and one of several early points where flesh begins to ooze down the narrative’s walls without any murder weapon in sight (yet). Interestingly, we know that Bateman is a killer, if not just simply psychotic, conceited, or otherwise somehow doomed, but at the points where his consumerist machinations establish clear in-groups and out-groups, we, as readers — whether consciously or subconsciously — have little choice but to project ourselves into the former if we are to salvage any hope of understanding him. New York City’s social game borrows from a similar rule-book: as much of a murderous, deeply unthinkable beast as it may be, its glitzy ethos and worldly promise make even the deadliest of downsides feel worth new secrets. The price for understanding is no longer being alive to understand, and it’s a price many are willing to pay.

“Bateman keeps saying, ‘I want to fit in.’ I felt that way too.”

In similar fashion to Babyfather’s strange album, though little explanation has ever come from its maker, there exists in American Psycho a difficult-to-follow pinball game between morbid humor, bare morbidity, and a “critique” of the culture that produces said morbidity. Google “American Psycho meaning,” and you’re more than likely to traverse pages upon pages of blogposts about consumerism and satire before you hear anything from Ellis himself. When you do, the controversial author might seem to exist in a weird permanent lax — years removed from the death threats, the store-wide bans, the vitriol from every activist group conceivable — and likely only be talking because some interviewer has asked him to revisit his cult classic in the wake of an anniversary or milestone. In one Rolling Stone retrospective for the novel’s 25th birthday, Ellis is prompted, as he has been many, many times, to explain what exactly American Psycho might have been getting at. “I created this guy who becomes this emblem for yuppie despair in the Reagan Eighties – a very specific time and place – and yet he’s really infused with my own pain and what I was going through as a guy in his 20s, trying to fit into a society that he doesn’t necessarily want to fit into but doesn’t really know what the other options are,” he says — in a run-on sentence that sounds oddly familiar. “That was Patrick Bateman to me. It was trying to become a kind of ideal man because that seemed to be the only kind of a guy that was ‘accepted.’ Bateman keeps saying, ‘I want to fit in.’ I felt that way too.”

That makes three of us. On the subway to my first day of tenth grade, bumps and sudden swerves threatening to jostle the book out of my hands, it mattered more to me where owning American Psycho would cast me in the city’s roving system of archetypes — Culture vulture? Real New Yorker? Contrarian-in-training? — than whatever, if anything at all, I would glean from its insides. I struggled with the first page or two and stuffed it into my backpack, never to touch it again until I slid it back across the Muhlenberg branch’s dust-covered desk, the librarian’s eyes glowering at me just like they did 48 hours prior.

🩸 🩸 🩸

“Before you can dance well, you have to figure out whether you want to dance at all — a decision American Psycho makes as easy as yesterday’s urine and today’s sweat.”

Four years after I braved the murderous eyeballs of suited strangers on a delayed Queens-bound E train, I stood, American Psycho in hand, at the front desk of a run-down department store in Times Square, as the Cardigans’ 1996 hit single “Lovefool” blared faintly from a faulty speaker. Some few hours earlier, I had finally made it up to — and subsequently squinted through — the first of the book’s many gruesome murder accounts. In that particular episode, an enraged Bateman verbally eviscerated a blind homeless man, sliced his eyes out with a knife, stabbed him to death, then proceeded to do the same to his innocent pet dog. “Love me, love me, say that you love me / fool me, fool me, go on and fool me,” the Cardigans pleaded over the department store speaker, poppy guitar chords ornamenting, somewhat hilariously, what was otherwise a hopelessly desperate romance tale. Gory imagery floating through my brain, it was difficult to decide between appreciating the song’s buoyant sound, or cowering beneath its vapid outlook.

Much of American Psycho is complicated by a similar funny-or-fatal dichotomy, created in large part by Bateman’s disjunctive mental dialogue. At several points in the book’s gap-infused plot-line, and especially when things begin heating up, he opts to suddenly change the subject to a favorite artist or band of his, dedicating chapter-length sections to thoughtful exegeses of their respective discographies. At one suspenseful point, immediately following the novel’s cinematic climax — an all-out police chase that, at its conclusion, sees Bateman frantically seek refuge from the helicopter searchlights illuminating his high-rise office — he writes at length about a niche jazz fusion sextet, never to mention the moment again. “Huey Lewis and the News burst out of San Francisco onto the national music scene at the beginning of the decade, with their self-titled rock-pop album released by Chrysalis, though they really didn’t come into their own, commercially or artistically, until their 1983 smash, Sports,” he deadpans, comically ignoring the catastrophic, plot-altering events that took place a single page prior. “Though their roots were visible (blues, Memphis soul, country) on Huey Lewis and the News they seemed a little too willing to cash in on the late seventies/early eighties taste for New Wave, and the album—though it’s still a smashing debut—seems a little too stark, too punk.” In the most popular scene from American Psycho’s cult classic 2000 film adaptation, a murder-crazed Bateman, played by Christian Bale, brutally axes down a clueless Wall Street colleague; blaring contradictorily behind it all is Huey Lewis and the News’ bubbly 1986 hit “Hip to be Square.”

A common fixture of New York City’s streets is the quintessential crinkly brown paper bag, Heineken bottleneck gasping for air through its top, rotting away somewhere on a not-so-touristy sidewalk. Oddly enough, years after a summer spent walking through as much New York City real-estate as possible, it was only when I employed a similar technique to read American Psycho under my parents’ watch — hiding it in the discarded sleeve of another, much more family-friendly novel — that I began to feel somewhat like the “real” New Yorker I sought to become in high school. This was, after all, what all of us were doing in some fashion: whether hiding alcohol from undercover cops, or hiding grimy literature from protective parents, a search for an underbelly was occurring, and it was turning the fixtures of our protection into fixtures of our suppression. These inner-city infrastructures make little sense, and everyone involved knows it, but — much like the New York City Police Department and my parents — the systems in place have been around far too long to be reformed, rather than simply eschewed. And so, The Cardigans’ happy-go-lucky First Band on the Moon blaring through my headphones, I trudged through chapters of unmentionable horrors, oddball contradictions making them all as deeply hilarious as they were deeply morbid. “Anyway, it set off something wicked in me,” Bateman writes of Huey Lewis’s “Slammin’,” midway through wrapping up his career-spanning retrospective. “And you cannot dance to it very well.” Before you can dance well, you have to figure out whether you want to dance at all — a decision American Psycho makes as easy as yesterday’s urine and today’s sweat.

🪓 🪓 🪓

By the time Patrick Bateman’s story comes to an end, we aren’t fully sure whether it really has. American Psycho barrels towards its close with several indicators, increasing in severity, of its deranged narrator being either caught, or coming close: a real-estate agent traps him into admitting something only the city’s serial killer could know; a testy cab driver recognizes his face as the one on all the “WANTED” signs across the city, and for a brief moment, appears ready to give him a taste of his own medicine; the aforementioned police chase sends him frantically admitting all his crimes to his lawyer over voicemail. What’s maddening about the story, and the city it exhibits, is that all of it, no matter how lofty or seemingly-tangible, amounts to nothing — regardless of how badly we want something to be there, nor how badly we want it to make sense. The real-estate agent simply tells him to leave and never come back. The worst the cab driver does is call him a “yuppie scumbag.” In the film’s final scene, the lawyer cannot be convinced that his client’s confession wasn’t a prank call. (In the book, the call is never spoken of again.)

And for the most part, we can’t really be sure that any of it happened at all. American Psycho’s narrative is tough to follow, in part because of how often characters are switched around — even up to the very end, where, at least in its film adaptation, Bateman’s lawyer insults him to his face under the strange assumption that he’s a completely different person. The last thing we hear Bateman say in the book is a lot like the first: an existential run-on sentence, muttered to no one in particular but himself and whoever is interested, or crazy, enough to listen: “Well, though I know I should have done that instead of not doing it, I’m twenty-seven for Christ sakes and this is, uh, how life presents itself in a bar or in a club in New York, maybe anywhere, at the end of the century and how people, you know, me, behave, and this is what being Patrick means to me, I guess, so, well, yup, uh…”

“But why bother? For years now, Bret Easton Ellis has been accused of being a racist and a misogynist, and I think these things are true; but like most things that are true of Bret Easton Ellis, they are also very boring.”

It will never make sense, but perhaps nor will its mastermind. Bret Easton Ellis followed up American Psycho with a string of somewhat similarly-rooted fiction titles, some of which sought to criticize celebrity-driven consumer culture, and others of which thinly fictionalized elements of his own upbringing. The first and only non-fiction book Ellis ever published was 2019’s White, an oddly-structured autobiography that stumbled along the tightrope between reminiscing about the past and complaining about the present. Common targets included millennials, cancel culture, and the “wussiness” of modern young people. In a scathing Bookforum review, Andrea Long Chu grappled with what, if anything, was to be done with its self-righteous rhetoric. “I could write an incensed review that fiercely rebuts White’s many inflammatory claims, thus giving the impression that they should be taken seriously; if my review were to go viral, it would likely trigger more bad coverage on pop-culture websites like Vulture and Vice; Bret Easton Ellis might trend for a bit on Twitter, where we would all take our best shots at dunking on this dude; and at the end of it all, the author would get to feel relevant again, and maybe finally write a movie that people actually liked,” she mused. “But why bother? For years now, Bret Easton Ellis has been accused of being a racist and a misogynist, and I think these things are true; but like most things that are true of Bret Easton Ellis, they are also very boring.”

The same can, and arguably should, be said of New York City — but for as long as its murderous boringness is cloaked in mystery, there will always be someone willing to die, or perhaps kill, for a shot at solving it. “THIS IS NOT AN EXIT,” American Psycho’s final words read, and it really isn’t.