A new Brigid Berlin exhibition balances obsessive documentation with questions of what any of it means.

SAMUEL HYLAND

In the opening moments of A, an odd 1968 book published by the equally-odd art-world character Andy Warhol, indistinct cell phone noises occupy nearly as much page-space as actual dialogue. The publication offers as real a glimpse into Warhol’s fabled New York City art milieu as likely exists—400-plus pages of transcribed conversations, many of which are either strange or morally questionable—but, perhaps just as effectively, paywalls any cultural insight behind layers of torturous monotony. The first page of the book lurches readers, somewhat cinematically, directly into the awkward beginnings of a phone call: “Rattle, gurgle, clink, tinkle / Click, pause, click, ring / Dial, dial.” Interestingly enough, it is at this scene-setting juncture, more or less, that readability ends and excess begins. “You said (dial) that, that, if, if you pick, pick UP the Mayor’s voice on the other end (dial, pause, dial-dial-dial), the Mayor’s sister would know us, be (busy-busy-busy),” Ondine, one of several Warhol Factory characters represented in the text, is recorded saying in the very next line. In order to continue reading beyond the first page, and through the many subsequent walls of similarly sprawling, unbroken text blocks, it becomes necessary to ask whether the boredom is worth whatever might lie on the other end of it. Life is quite similar—the vast majority of it is extremely mundane; the promise of a book, perhaps, is the prospect of fast-forwarding through the monotony, past the rattle-gurgle-click-tinkle, beyond the dial-dial-dial, and into the immediately invigorating. What makes A singular is the very thing that makes it unreadable: wherever the significance may be hiding, monotony will always be there, unapologetically, to mask it.

“Sooner or later, as the Instagram slideshows and polaroid boxes pile up, the question becomes one of what was ever worth remembering, and by who.”

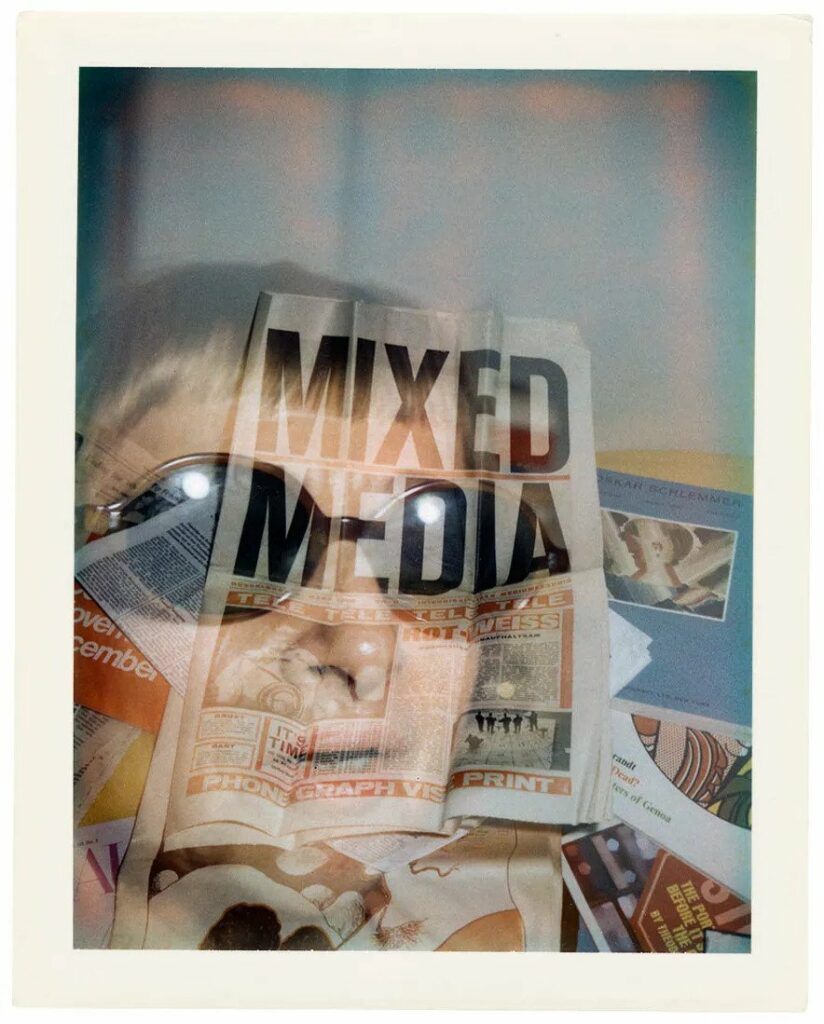

Somewhere in A’s sprawling cast is Brigid Berlin, who goes by “the Duchess,” and only appears in one conversation. It’s a roving dialogue, much like the others, that traverses a whiplash-inducing array of chosen topics—dinner plans, presumably large penises, phone calls, what’s on television—but either lacks any real substance, or makes said substance extremely difficult to look for. Both Berlin’s presence in Warhol’s New York City, and the hefty archive that’s left of it, hinge largely on a similar impulse: documentation, but perhaps without any concrete purpose besides the loose possibility of someday remembering, or being remembered. A popular 20th Century adage, repurposed for the era of cell-phone cameras, demanded preservation behind cries of “Picture or it didn’t happen!” Perhaps its closest modern-day appendage is Instagram, where decades’ worth of formal photographic instincts have festered into a strange race towards a sort of radical casualness. To have a photo taken of oneself and shared with others is nothing new; to have that photo be as intentionally effortless-looking, candid, unkempt, or unsexy as possible is less about presentability, and more about collective recollection. A 10-slide Instagram photo dump is, not unlike Berlin’s lifelong practice, a wielding of excess to make a familiar declaration: “I was here,” one might say, “and now, neither of us can forget.” Sooner or later, as the Instagram slideshows and polaroid boxes pile up, the question becomes one of what was ever worth remembering, and by who.

At The Heaviest, a retrospective exhibition on Berlin being shown at Vito Schnabel’s Greenwich gallery through August 18th, the hypothetical seems to hang over her life’s work like a specter. One recent Thursday evening, as formally-dressed revelers trickled into the showroom—decked out in winsome burgundy wallpaper, as homage to Berlin’s recently-sold Kips Bay apartment—a strange mixture of trepidation and intrigue dotted the throng’s cautious movements. There was quite a bit to be made sense of. On one wall by the door, a glass case contained a box packed with typescript-labeled cassettes (“SEPT 6, 1960 Mom & Dad call b’day,” “Salvidor Dali [BLANK],” “MAY 2 8 1973 MEM. DAY / GIMBELS with Andy #0-end”); stationed a foot or so away was a pair of overhead headphones, through which some of the cassettes’ contents played non-stop. When I threw them on, there was a rattle-gurgle-click-tinkle not unlike the one memorialized in A’s opening scene, followed by the semi-tense beginnings of a conversation between Berlin and her mother, a matronly conservative woman she often clashed with. Directly across the room, stationed in another glass box, was a New York Observer spread in which an older Berlin spoke candidly about their strained relationship. “Ms. Berlin is fondly remembered by many as the plump, Fifth Avenue-bred Warhol acolyte who lolled around shooting whipped cream into her mouth and amphetamines into her ass,” an introductory sentence read. “(But) Brigid’s mania for recording conversations, polaroiding and, most importantly, monologuing informed and shaped large chunks of the Warhol canon.”

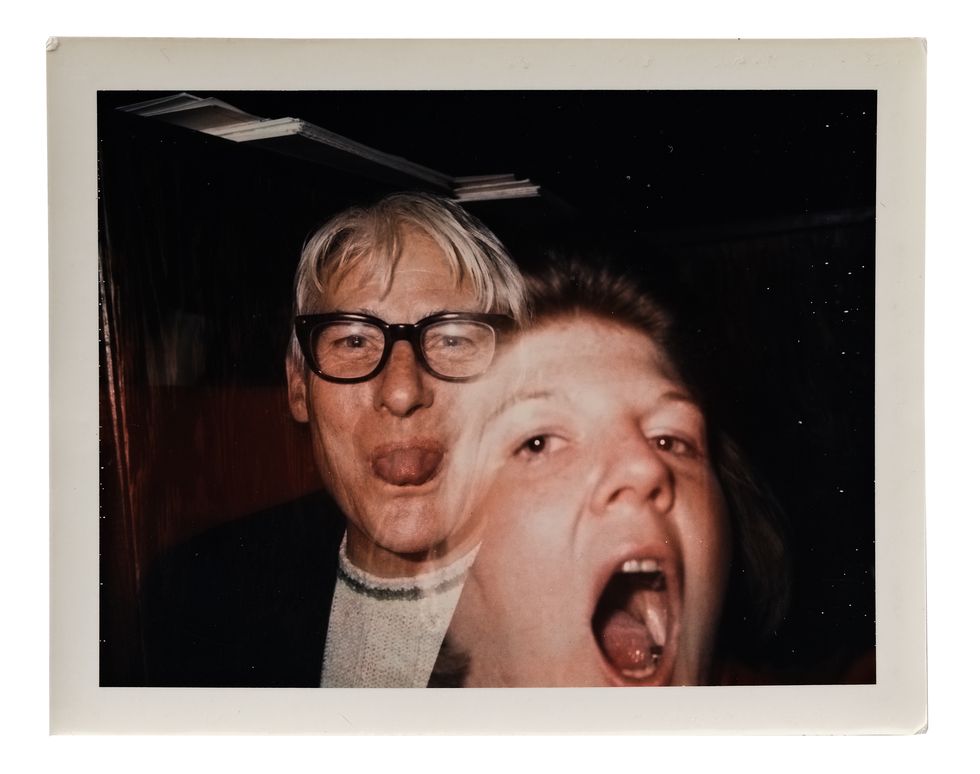

Perhaps, decades after her Warhol Factory superstardom and three years after her death, it’s this familiar tightrope—between careful art and careless living—that makes Berlin perennially relevant. Somewhere along the same wall that featured the New York Observer spread was a sizable grid of polaroids, their rectangular aspect-ratios and white borders bearing uncanny resemblance to early-stages Instagram layouts. Visually speaking, it was difficult not to feel some vague sense of kinship with Berlin and her fellow Fifth-Avenue art-world characters, who had seemingly been enticed by the same impulse we yearn to satisfy via content-sharing apps. Yet what seemed to separate us from them, and made the exhibition doubly jarring, was the prospect that they had to live among the spatial debris of their mnemonic excess. Like the hypothetical Instagram photo-dumper, the circle was forced (as were we) to remember their hijinks, but there must have come a point, or several, where remembering grew literally inconvenient. Memory is an object that takes up space: at the neuron level, at the bedroom level, at the apartment level, then if you’re important enough, at the auction or exhibition level when you die. Standing there in a physical remodel of Berlin’s living space, surrounded by ephemera of the things she desired to remember, it felt ever so slightly like the walls—as beautiful as they had been—were closing in.

Among such ephemera was a set of thick volumes, their tattered pages adorned by Berlin and co. with original artwork or photography related to various vulgarities. The most impressive of these, perhaps, was the “Topical Bible”: a hefty 500-page “Cock Book” she carried around with her for years, garnering inscriptions, sketches, polaroids, original artworks, and various other lewd insertions from the artists she shared a social world with. Across the books’ contents, some work felt worth keeping—a compelling page from the Topical Bible featured a collage of loose fingers protruding from a devilishly-grinning mouth, a sort of ingeniously-haunting fashion magazine spread come-to-life. Other work, on the other hand, boiled down to the same question ultimately begged by impulsive online content-sharing: what is worth remembering, and by who? In one of them beneath the glass, a feces-stained tissue used by Andy Warhol—still colored in a fading shade of light brown—clung to an opened page.

“I can’t stand cell phones and I don’t know one single thing about the computer. I have a friend come that lives in my building to check if I have emails. I don’t even know what to google.”

In a 2015 Q&A published in Warhol’s Interview magazine, Berlin seems, maybe a bit unexpectedly, averse to the modern outgrowth of her prolific documentation-driven practice. “I don’t really care about it,” she says, asked whether she wishes she’d come up with the word “selfie.” “But it wasn’t something that was new. I have never taken a selfie per se with a phone. You can take them with a phone, right? I’ve never done that. I can’t stand cell phones and I don’t know one single thing about the computer. I have a friend come that lives in my building to check if I have emails. I don’t even know what to google.” The interviewer tells her she can start by looking up her own name; she says “I just can’t deal with it.” As much as we document ourselves, it’s a familiar sentiment: we only really scrutinize, cringe at, or loathe ourselves in relation to other people and their eyes. Singing in the shower is so natural of an impulse that it’s become a cliche; hearing one’s own voice in a video recording is grounds for suicide. Instagram posts are helpful ego boosts when we’ve mulled over the photos, tweaked out tiny insecurities, established target audiences and imagined their reactions. But eventually, the feelings we harbored in those moments—chief of them all being impulse—fade, and a day comes where we cringe at versions of ourselves we once thought were flawless. You can only look at your image for so long without a sense of existential dread, and so, as was the case with Berlin, those memories pile up in corners, crevices, cassettes, and eventually collections: too insignificant to be revisited, but too important to be thrown away.

A recent thinkpiece published in the New Yorker grapples with modern-day museums, and their struggle to accurately exhibit video games. “Games are time-intensive, endlessly variable experiences,” the magazine’s Julian Lucas mused. “You can no more really ‘play’ one in a gallery than read an entire novel while standing in line at the supermarket.” Though bred from a different context, Berlin’s exhibition, and perhaps our own self-mythologizing practices, too, face a similar Catch-22. It’s hard to re-experience a full-fledged life, let alone an era, in a moment spent underneath overhead headphones, in a camera roll, on a content-sharing app, or in a gallery—even if it’s decorated to look just like your old apartment.

🏢🏢🏢

“Why can’t I go outside and look at things just to look at them because I think they’re pretty?”

A week or so before The Heaviest opened, Vito Schnabel Gallery and the Tribeca Film Festival jointly held a private screening of Pie in the Sky, a 2000 documentary on Berlin that showcased her evolution from jet-set debutante to fast-living Warhol superstar. At a late point in the movie, a rapid-pace monochrome montage flashes through scenes of her ruminating, somewhat panickedly, about what her documentation might mean in the grand scheme of things. “I couldn’t go away, because I had 500,000 tapes with me,” she says in a quasi-anarchistic drawl, presumably in a spiel about moving apartments. In the following few bursts of speech, she’s crazed, in a way that feels half like self-satire and half like genuine concern. “I consider my eye the Polaroid camera now, and I consider my ears the tape recorder,” she continues. “Why can’t I go outside and look at things just to look at them because I think they’re pretty? Why do I have to get everything down? You’ve got to take a typewriter out and put the typewriter on the seat of the motorboat, kneel down, and start typing with a smirky look on your face, because you don’t have any film to film it, so you don’t want to look at it. Can you believe that? Can you believe anybody could be so sick?”

In similar nature to her art, as time goes on, Berlin’s concerns feel less like relics of her time, and more like preemptive outgrowths of a modern impulse. A commonly-used internet dismissal urges interlocutors to “touch grass” instead of fixating on hyper-online problems—an act that, as its overtly-simple nature makes funny, is perhaps far easier said (or typed) than done. Berlin stumbled along these very same boundaries between fantasy and reality, but in a way, her version of the tightrope was more pressurized, and more existential. Doubly tugged at by the conservative-socialite upbringing she rejected, and the perverse New York City art milieu she embraced, obsessively documenting things grew to be an unconventional means of self-medication. “Her art is really about this obsessional kind of personality,” the filmmaker John Waters suggests late in the documentary. “I think that’s her therapy. I think without those obsessions, Brigid might be in the most expensive mental institution in America.”

“Brigid is a conceptual thinker from a good family. Though she has moved to the wrong side of the tracks, her good breeding still shows.”

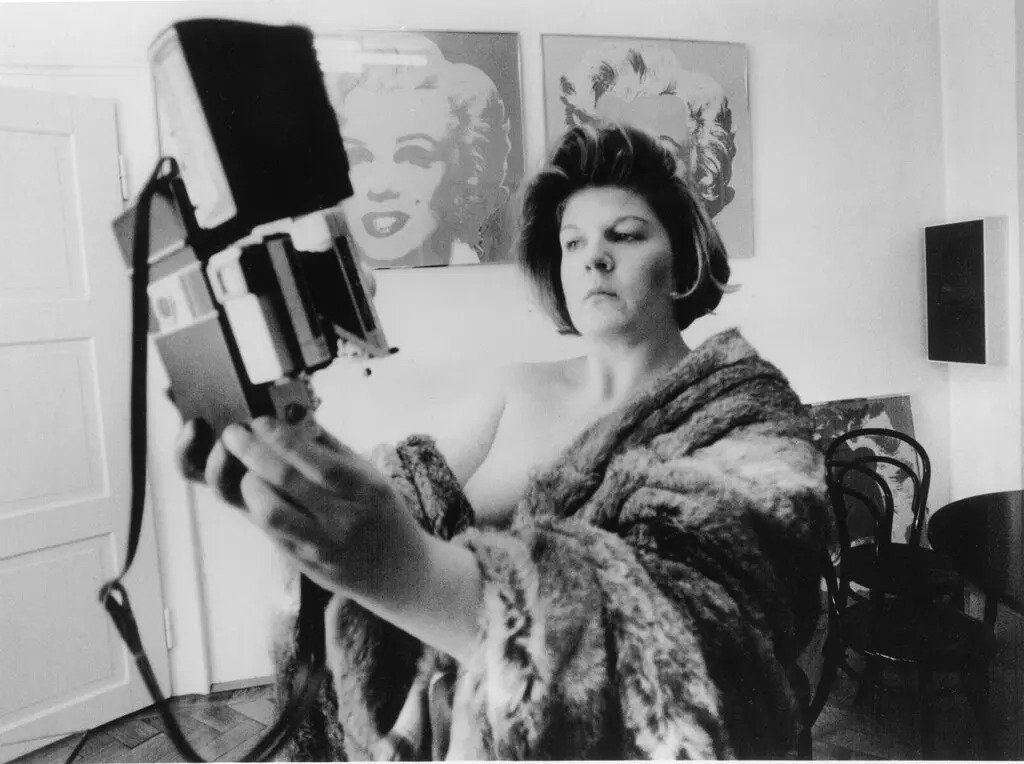

In terms of the Polaroid camera’s cultural cache, history has been kinder—despite Berlin’s visceral relationship with its use—to Andy Warhol, for whom Berlin was both a close friend and something of a muse. Warhol, too, is remembered as an innovative mythologizer of quotidian moments, but it remains questionable how much of this touch was borrowed from Berlin, and how much was actually his own. In Pie in the Sky, the competitive artistic tension underlying the pair’s kinship is carefully alluded to. At one point, on a brightly-lit set, crackling VHS footage sees Warhol nagging Berlin to participate in an unspecified studio recording. The problem, for Berlin, is that the studio lights feel too ritzy and professional—perhaps reminiscent of her upbringing—for her to be able to speak as candidly as she’d like. “You know what’s a better way, then? I have a better way: if I use that telephone over there, and you go in your office—,” she begins saying, before Warhol cuts her off.

Retrospectively, it appears more like Warhol used Berlin for his art than the other way around. Most popular of these examples is Chelsea Girls, Warhol’s 1966 indie film that broke through the underground and into the mainstream press—to the delight of a depraved art-slash-drugs-slash-porn enclave looking for validation, and to the great chagrin of Berlin’s parents, who saw the film upon stumbling across a Time magazine review and proceeded to cut their daughter off in a blinding fury. In a place where one of Berlin’s many mother-daughter phone-call recordings might have been a natural-feeling addition to the documentary, viewers are instead treated to the aging artist in a split-screen with her younger self, recalling the minutes-long lecture she received after Chelsea Girls, as if she had it down verbatim: As far as I’m concerned, I’m not your mother and your father’s not your father, she closes, with an eye-roll, and the scene ends.

That Thursday evening in Greenwich Village, The Heaviest was set up in a loose chronological order that snaked around the walls. To your left upon entry lay encased ephemera relating to Berlin’s childhood; the artifacts grew more grotesque as you moved rightward, and she got older. Interesting, visually, was the fact that the space both began and ended with her parents: interrupting a room-spanning wraparound of work, a sole door separated Berlin’s childhood family portraits from the headphone set featuring tense mother-daughter dialogues to be had later in life. In one of these family portraits, taken in a visibly well-prepared set, an infant Brigid sits in the arms of her mother, who is donning a half-smile that appears to be rehearsed. Self-representative media held a different importance to the senior Berlins than it did to their estranged daughter: Richard Berlin, her father, sat at the helm of the Hearst Corporation, a conservative news empire that called Joe McCarthy a friend and communism a mortal enemy. (In various photos across both The Heaviest and Pie in the Sky, he is showcased dining with a number of controversial Republican presidents. “I would pick up the phone and it would be Richard Nixon,” Berlin once said of her upbringing.) Though primarily social, it’s interesting to see her trajectory from conservative beginnings to art-world laissez-faire as a visual evolution, too. Stationed a few feet to the right of the baby photo, directly above the Topical Bible, was the polaroid wall: an obscure monument to abstraction that served, and may to this day, as a strange form of liberation. In the very beginning of Pie in the Sky, a freeze-frame Warhol quote seems to glue together the chasmal tension The Heaviest accentuates: “Brigid is a conceptual thinker from a good family,” he says. “Though she has moved to the wrong side of the tracks, her good breeding still shows.” Within the exhibition’s wallpapered walls, it didn’t feel like he was wrong.

“Right now, I feel like I’m definitely at rock bottom. And sometimes I wonder if it’s worth it to pick myself up, dust myself off, and get on with it again.”

Several scenes in Pie in the Sky are filmed in the New York City of 1999, with Berlin narrating her way through streets and buildings she once knew in far different contexts. In what is perhaps the most unnerving of these moments, she’s giving a monologue outside the Chelsea Hotel, where, decades prior, the filming of Chelsea Girls cemented her niche status in Warhol’s bohemian mythos. After a chance run-in with the artist Richard Bernstein—“You telling the old story?,” he asks—the two talk through memories en route to the main lobby, until Berlin abruptly stops walking. “I want to get out of here,” she says suddenly, her smile fading. Questioned by documentarians on her way out, she speaks between long pauses, in erratic half-sentences. “I like to go back, but I don’t really like to go there,” she says. “It’s kind of scary. I never want to come back here.” Part of what makes the sentiment grim, today, is the unsettling follow-up question it poses to the ever-modern what is worth remembering and by who—sometimes, it seems, the memories cherished by the masses may be the ones we’re frightened by the most. Two entities, ourselves and our watchers, are immediately served by self-mythologizing practices. Who inherits the burden when we’re done?

By the time Berlin died in 2020, she had become somewhat identical to the mother she famously opposed. Throughout the documentary, a tense underlier to her wild youth is her journey, in old age, to grow significantly healthier. 60 years old at the time of Pie in the Sky’s recording, she’s slim and winsome, an uncanny physical embodiment of the matronly socialite her parents once hoped she’d become. At several points, viewers are shown footage of the buzzy woman obsessively chopping lettuce, documenting the things she’s eaten (and plans to eat) in a little notebook, or giddily making green-centric food orders over the phone. For a long time, it feels like she’s winning—a weight issue she long grappled with, whether via her parents’ judgment or her own, is finally more or less in the rearview. But by the film’s end, she has gone on another food binge, and gained ten pounds in less than ten days. “Right now, I feel like I’m definitely at rock bottom,” she says, flummoxed. “And sometimes I wonder if it’s worth it to pick myself up, dust myself off, and get on with it again.” The moment, the exhibition, and Berlin’s legacy at-large are testaments to the tricky places where real life catches up with memory: sometimes dreadful, sometimes cathartic, always ever-so-slightly unsettling. That Thursday evening, as professional cameras flashed and cell phone cameras angled themselves towards the glass boxes, it was odd to wonder whether these would someday be worth remembering, and by who. The sole way to find out glared from the faux-wallpapered walls: to live long enough.