A dark 90s teen epic anticipates a darker future.

BEN ARTHUR

Coming-of-age films often begin with camera pans into the bathrooms of frenzied protagonists, and Nowhere is no different. Dark – a young, happy-go-lucky bisexual, played by heartthrob James Duval – is getting ready for school, and his defensive mother, curlers-in-hair, is yelling at him: “You’re going to be late!” We’ve seen it a million different times, whether it’s Risky Business or Back to the Future. Gregg Araki, who directed the flick, had likely seen it a million times, too — enough, at least, to subvert the trope with a sex-crazed panache familiar to his sprawling oeuvre. The auteur spent his formative years in California: born in Los Angeles, undergrad at Santa Barbara, and back to Los Angeles for film school. He was born at the right time, old enough to take influence from the cinema’s French New Wave (lots of Jean-Luc Goddard), but young enough to see the New Wave bands who stopped by (The Pretenders, The Clash, The B-52s — you get the idea). His world was, and is, fueled by the philosophy that rules above all: sex, drugs, and rock and roll.

“In order to stand up against fascist ideologues or extremist legislatures, we stand to learn something from the past: whether that’s examining the scorching homophobia of the past century, the downstream effects of the AIDS crisis, or simply the way LGBTQ culture thrives.”

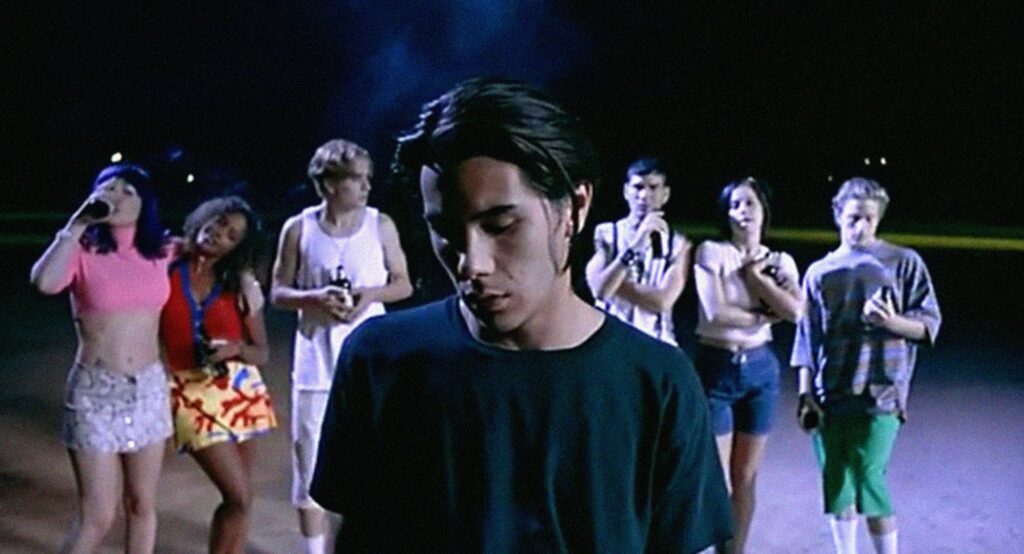

It is this timeless aphorism, one intrinsic to most Araki films, that is on display within seconds of Nowhere’s opening credits. We find our protagonist Dark caught in a moment of tension, pleasuring himself to the thought of a menage-a-trois with his girlfriend and her “close friend” (read: sexual partner). The viewer is cut between this polyamorous desire and the steamy shower of a suburban home at rapid pace, evoking hyper-capitalistic subliminal messaging. For those unfamiliar with the idea, market researcher James Vicary claimed significant boosts in sales when he flashed advertisements to viewers at a blistering 1/3000th of a second. His 1957 experiment, which caused a minor moral panic across the nation, was later considered fraudulent, but Araki still takes the central principle to heart: melding late-state capitalism with the ethos of a violent nymphomaniac. The sheer maximalism of this scene, placed in its short 82-minute run time, debases expectations and leaves viewers with a vague sense of what’s about to happen next: a melding of intellect, culture, and status into a homogenous psychedelic blur. After this particularly jarring opening scene, Dark runs into his friends, who discuss the fictitious bands “Girl + Human Sex” and “Deadpuppy.” The worldbuilding of Nowhere centers on these humorous yet critical elements, highlighting the restless overconsumption of ‘90s teens. The group – complete with outlandish nicknames like Egg, Dingbat, and Handjob – talk about their “Human Sexology” and “Modern Society” classes and use phrases like “the whole falafel” or “ditto, hunnybug” to describe their heroin addictions and sexual proclivities.

Even weeks after watching it, I can’t stop thinking about this scene, alongside the rest of the film. The distinct soundtrack, the intentionally-cryptic settings of Los Angeles, the maximalist set design and fashions, and above all, the subversion of heteronormative values all culminate to challenge the coming-of-age genre. Araki makes it his mission to break down the worlds constructed by the Molly Ringwalds and John Hughes, and in the process, creates a collective consciousness for LGBTQ teens deserted by society. In a political climate that sees the group increasingly lambasted, attacked, or even outlawed for simply existing, reaching back to touchstones like this one feels pertinent. In order to stand up against fascist ideologues or extremist legislatures, we stand to learn something from the past: whether that’s examining the scorching homophobia of the past century, the downstream effects of the AIDS crisis, or simply the way LGBTQ culture thrives.

The modern-day “teen film” that explores high-school anxieties around sex, school life, and growing up became a Hollywood phenomenon in the 1950s, when features like Rebel Without a Cause and East of Eden probed into the disillusionment of post-war adolescents. The genre truly blossomed in the 1980s with Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club, both directed by John Hughes. These movies prided themselves on the exploration of common tropes: the jock, the brainiac, the rich snob, the burnt-out delinquent; the clique working together against the pervasive high-school establishment. This sums Hughes’ writing style, centered on adolescent drama in white middle-class suburbs. His works formulated the basis of what we now know and love – leaning on the “Brat Pack” of actors like Rob Lowe and Molly Ringwald.

Multiple factors contributed to the emergence of youth-centered filmmaking: chief among these, perhaps, being the economic growth of the ‘50s and ‘80s. Cinema scholar Elissa H. Nelson argues that the latter, combined with the formulation of new media technologies like television or VHS, led to the renewed interest in youth culture from studios. In her 2017 paper The New Old Face of a Genre: The Franchise Teen Film as Industry Strategy, she states:

“Historically, one of the strategies Hollywood relies on when there are threats of audience attrition because of competition from new media is to increase production of teen films. The hope is that by making films with young actors in lead roles and by telling their coming-of-age stories, two essential elements that are hallmarks of the teen film genre, the films will appeal to the most reliable audience segment: the youth demographic.”

These factors converged yet again in the 1990s, as GDP rose steadily, and DVDs and the Internet posed a convincing threat to the movie-going establishment. Films like Dazed and Confused and Can’t Hardly Wait (named for the excellent Replacements song) built upon the foundations of James Dean and Molly Ringwald, while some, like 1995’s Clueless, toyed with these conventions, expanding the style to critique the idealized institution of California and the wealthy that inhabit it.

Only two years later, Araki’s style took the space these films occupy and set it ablaze. Billed as “90210 on acid,” the initial aphorism is no more true than its unorthodox wardrobe and set design. From the background actors to the main performers, you have to think that the term camp was made for Araki. In one scene, as Dark waits at a bus stop emblazoned with the words “REPENT NOW” in scrawled white spray paint, three “valley girls” talk in upspeak about who’s invited to Juicyfruit’s party that night:“What about Jason? I’m going with Jason! What about Tomas? I thought you were going with Tomas? Eileen is a whore! Is Richard the surfer with the hair lip that drives the Black Jetta?”

The group, wearing retainers, brightly colored heart-shaped sunglasses and skirts, stick out like a sore thumb against the main character and his quasi-punk aura. As the three discuss their possible suitors, Dark stands off to the side, wearing all black and smoking a cigarette. His hair falls down onto a pair of thin sunglasses as he stares at the dart and moves it towards his finger in an act of youthful nihilism. We enter a cyclical enumeration of unanswered questions about these women until, in an absurdist twist, a lizard monster rayguns the three into oblivion. The girls’ over-the-top wardrobe, alongside the general depiction of the three characters, pokes fun at the common trope of stuck-up Southern Californian high schoolers—up until the bitter end.

“Araki focuses his critical eye on the “old fashioned” ideals that monogamy and religion represent, adding another layer to the diametrically opposed youth. He paints a society out against their creed: a world where misfits and fuckups like them don’t belong.”

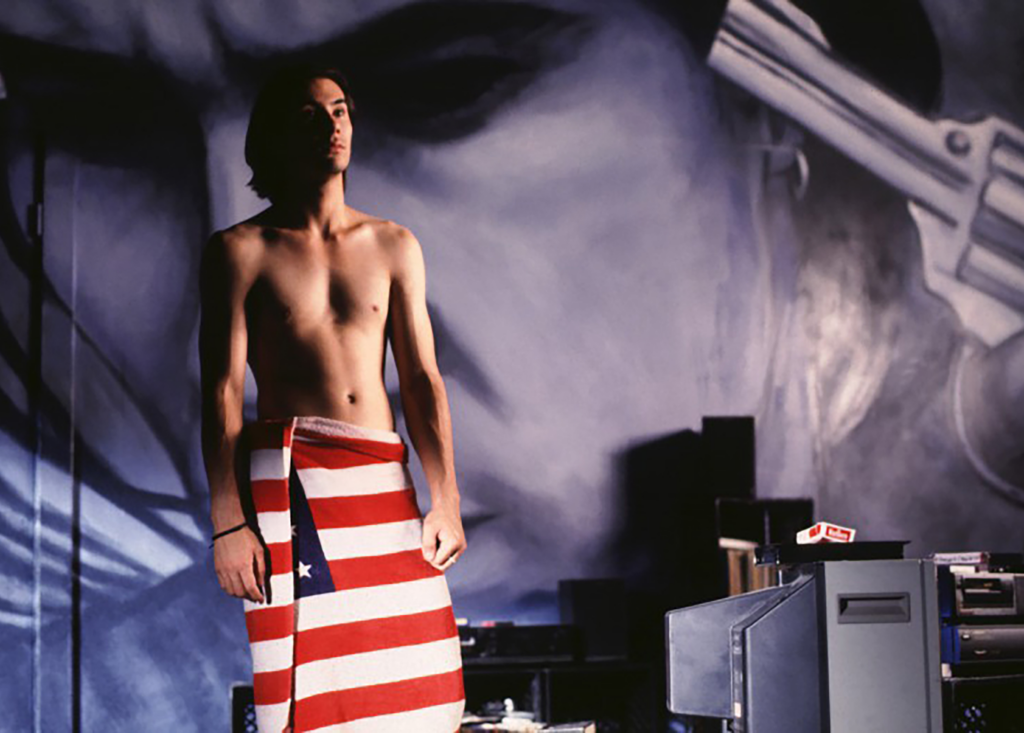

Nowhere takes place in an unknown location in California, likely Los Angeles. The landscapes are nondescript and strung out: a warehouse; a pretentious industrial coffee shop called “the hole”; the quintessential fixture of the characters’ vastly different bedrooms. They are absurd as the rest of the film: with partitions covered in television test patterns and large dots reminiscent of the game Twister. We first see Dark’s room post-shower-scene, arms draped around an American flag towel. “Bitch!” he yells out to his overbearing, emotionally abusive mother as the towel drops. A messy room awaits him, full of VHS tapes, existential literature, and baggy-fitting jeans. The walls are painted a dark hazy blue: one adorned with a caricature of himself holding two guns to his temples, the other with a swirling pattern. Eventually, we cut to the obsessed drug dealer Handjob, who surrounds himself in a shrine to tube TVs and SMPTE color bars. After a quick phone call (and a hit of heroin for good measure), he hears a few sharp knocks from Cowboy: who’s looking for his strung-out boyfriend Bart. He was last seen at the dealer’s home, and despite a few loaded threats (yanking a chain off Handjob’s neck and knocking his “KILL YOUR TV” hat from his green shaved head), the dealer doesn’t let up on his whereabouts.

The only time we truly escape this setting is earlier in the film, when Egg and her unnamed Australian movie-star hunk hang out. In a picturesque mountain valley, he talks about the pains of celebrity status — being spotted everywhere, no one “truly understanding you,” et cetera et cetera. They walk and walk, but one can’t help but notice, behind his aloofness, the sly presence of a far darker undertone. The viewer’s intuitions are later confirmed when he violently rapes her while a televangelist espouses the wonders of capitalism and religion. Televangelism is one of the more overt motifs in the movie — another character is brought to the brink of suicide after watching the same broadcast. Acting as a foil to the youthful nihilism of Dark and his friends, their parents remain transfixed to their televisions, watching the pastor as he practically begs for money and status in a decaying world. In one scene of many, one of the youth transfixes on recent religious fervor in South Cambodia – somehow making their discussion pretentious with an animalistic zeal. In this manner, Araki focuses his critical eye on the “old fashioned” ideals that monogamy and religion represent, adding another layer to the diametrically opposed youth. He paints a society out against their creed: a world where misfits and fuckups like them don’t belong.

In the Journal of Film and Video, Kylo-Patrick Hart analyzes the settings of Araki’s The Doom Generation. The 1995 dark comedy, alongside Nowhere and Totally Fu***ed Up, makes up the “Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy.” In these three films, Araki injects absurdist, existential ideals into three common tropes around teen movies. The Doom Generation focuses on the “road movie,” with Duval starring alongside Rose McGowan and Jonathan Schaech. The trio of drifters scour the ruins of an enigmatic California, eventually outrunning the police and encountering a group of Neo-Nazis in an expansive warehouse. The three, named after colors (Jordan White, Amy Blue, and Xavier Red, respectively), explore their desires and sexual longings in a setting stuck within the binary of “utopia and dystopia.” Hart writes,

“By placing these young sexual adventurers on the road, Araki appears to create a utopic space within which they can explore their most intimate desires…Simultaneously, Araki’s visual treatment of Los Angeles in this and other films is another instance of his transformation of road movie conventions; he offers a dystopic setting as the site of utopia. Araki’s LA features none of the typical landmarks; instead, he focuses on overcrowded clubs and undercrowded streets and parking areas, frequented by the occasional transient, places that could be anywhere, as if his characters are trapped in a boundless abyss.”

The framework is applicable to Nowhere, which takes on a dystopian setting of house parties ravaged by aliens and nightclubs ravaged by rapey Australians. The characters, trapped within this “boundless abyss,” are free to explore their desires, acting in diametric opposition to the picture-perfect settings of typical teen films. With this, Araki comments on those viewed as transgressive outlaws and rejected outcasts – especially within the LGBTQ community. This work isn’t far removed from the AIDS crisis of the ‘80s or even the Hays Code that barred homosexuality, “transgressive or perversive desire,” and even sex itself from being depicted in Hollywood. The production guidelines ruled over the industry for years, enforcing morality from a straight, white, heteronormative viewpoint. This was challenged by a number of directors and actors, including the aforementioned Rebel Without A Cause, which portrayed a “coded” trope of a gay teenager, and the 1961 British film Victim, which documents a blackmail scheme against gays in a time where homosexuality was illegal. The restrictions ended in 1968, being replaced by softer MPAA guidelines. But in the years following, taboos limited the depiction of LGBTQ individuals and relationships. Despite hostility from the general public, flicks like The Rocky Horror Picture Show became iconic cult classics, and Bill Sherwood’s Parting Glances, released in 1986, wrestled with the effects of the AIDS crisis on a New York editor and his partner. Six years later, Araki tackled the issue in The Living End, where a gay couple reckons with their positive diagnoses through homosexual desire and violence. Araki upkeeps this theme in his later works, including Nowhere, incorporating transgressive and damaging desire throughout.

In doing so, Araki lives in the generational canon of gay cinema, urging viewers outside the norms of how relationships in the LGBTQ community are depicted, yet also making audiences understand the foreign emotions that young people felt during this time period. By injecting a dystopic nihilism into his works, Araki reflects the cultural era that gay teens lived under in the ‘90s — the downstream effects of the AIDS crisis combined with generations of blatant homophobia. As with many countercultural movements, many gay teens felt forced into the shadows, where punk music and rebellion reigned above all. Their idiosyncrasies, whether it be how they dressed or the philosophers they read, revolved around the idea that they didn’t belong: that society didn’t view them as “normal” or “typical.”

Comprised primarily of shoegaze and post-punk bands, the score is an immaculate backdrop for the wide, static shots of parties, cars, and sex. To open, Slowdive’s cinematic soundscape “Avalyn II” accompanies the hazy title credits. As the movie progresses, bands like Cocteau Twins, Mojave 3, and The Jesus & Mary Chain serve as a pensive melodic accompaniment to scenes. One particular scene begins with two characters discussing their relationship woes as Lush’s “I Have The Moon” plays in the background of a bar. “My palm itches,” Alyssa exclaims. “Where’s your twin brother?,” the other asks. A match cut jumps us to a palm reading as Thurston Moore’s abrasive Jazzmaster launches at breakneck pace. Sonic Youth’s 1992 B-side “Hendrix Necro” fades in as Shad, Alyssa’s brother, asks “What do you see?” “Death!,” the palm reader responds, biting off a piece of a chicken leg. “Cool!,” he says, and proceeds to make out with his girlfriend (as one does).

“Instead of furthering a utopic vision of adolescence, Araki injects existentialist dread into his films, providing no way out for his characters. They have accepted their doomed fates in this world, so all that’s left to do is explore their atypical desires without inhibition.”

The soundtrack echoes Araki’s overarching ideal, capturing a certain nostalgia and creating a time capsule of embittered teenage life. This becomes particularly evident in an euphoric party scene, checkered with diegetic, bass-heavy melodies and an unwavering fashion sense. The climactic standard holds a lofty significance in Nowhere, as with the genre itself. The typical concluding setting of every teen movie known to man is once again showcased, with characters rolling up in convertibles to the lofty mansion of someone that everyone barely knows. We see shots of huge rooms full of people, vodka, cocaine, cheap beer. One can imagine the excess in this seemingly-apocalyptic setting: everyone too drunk to care about anything, much less notice the world actively being overtaken by aliens. The tropes abound in this concluding portion: smoking cigarettes by the pool, fight scenes, and the classic “we gotta talk” moment between a couple on the brink of breakup. Araki takes these commonalities and uses them as fuel to further the group’s ideals (or lack thereof). In typical Araki fashion, the fight scene turns bloody quick, as two characters throw punches, and eventually, in a development Andy Warhol might have gleefully endorsed, one bludgeons the other with a soup can.

For the latter scene, polyamory is injected into the couple’s relationship woes. Dark’s girlfriend Mel has just been whisked away by two bombshell Ken-types, strangely named Surf and Ski. The blond duo, clad in sunglasses and harnesses, live out their three-way dreams while Dark sulks among the throngs of partygoers. Eventually, the couple talk in a bathroom, per usual, where they reach an unresolved conclusion, and, similar to his emotional troubles, the party takes a turn for the worse. Ducky, who has just learned about his sister’s rape and untimely demise, attempts to drown himself and is given improper CPR. At the same time, the aliens Dark has been envisioning finally invading the party, abducting a group of women.

Instead of furthering a utopic vision of adolescence, Araki injects existentialist dread into his films, providing no way out for his characters. They have accepted their doomed fates in this world, so all that’s left to do is explore their atypical desires without inhibition. In this manner, Araki inverts the bildungsroman, the typical hero’s arc. In previously mentioned movies, unsuspecting protagonists endure romantic pain and suffering but always “get the girl” in the end, whether at prom night or in a jam-packed airport terminal. Even seemingly “radical” works like 1967’s The Graduate, where the neurotic, disillusioned Benjamin Braddock becomes entangled with a mother and daughter pair, contains this cliche moment at the end. As he boards a bus, the protagonist has a final moment of anxiety, tension, and grief: realizing his unorthodox path of stealing the bride from the altar may have consequences that could have been avoided if he followed the socially acceptable route. Araki complicates this desire by creating a bleak and depressive worldview for his ill-fated characters, one where no proper outcome is resolved, especially within the purview of what is socially acceptable. He hints at this as Dark and his new sexual partner lay in bed together, and perhaps, even if for a second, the past hour and a half of tension seem to be resolved. But, in a Kafkaesque turn of events, the hot blond’s chest is ripped open by an alien cockroach. In this, Araki makes one last absurdist jest at heteronormativity and typical tropes that populate coming-of-age films, and as the credits roll, the line between what you know happened and what feels hallucinated blurs: hundreds of colorful, absurd, atypical passions synthesized into 82 minutes. All one can know is a new appreciation for roach exterminators.