Can a centuries-old cultural relic survive a change in meaning?

🩸🩸🩸

SAMUEL HYLAND

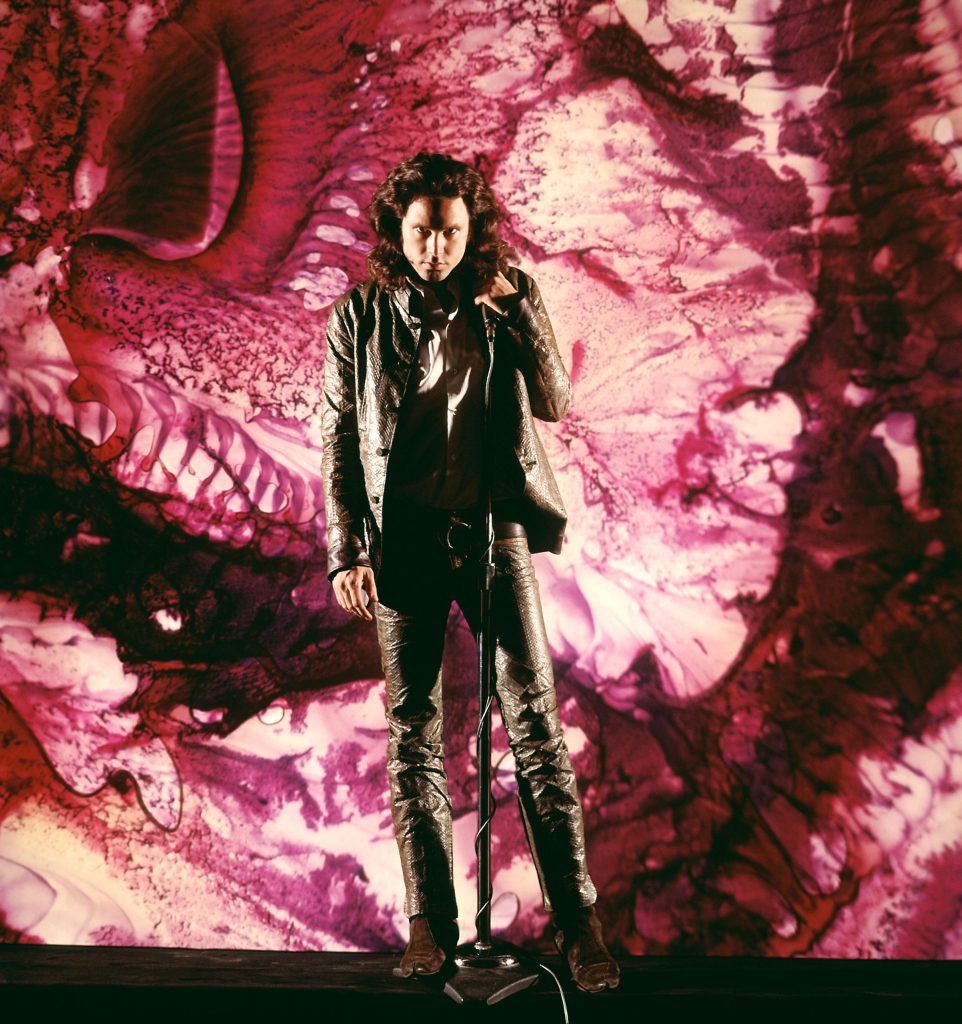

In what grainy footage exists of The Doors’ 1968 headlining set at the Singer Bowl, a Queens stadium-slash-venue that once held upwards of 18,000 sex-crazed teenagers, Jim Morrison’s leather-outfitted figure is flanked by police officers en route to a brightly-lit, barricaded square. In many ways, the visual feels a lot like the frenzied beginnings of a boxing match—the stage, like a ring, is in the middle rather than the front; the guards shield Morrison from horny fingertips the way an entourage might shield its center from potential attackers; the band is ushered through the very crowd that will, within minutes, relish in the violent sacrifice of their bodies. By this point, the Doors had been at the height of their legend: dubbed “America’s Rolling Stones,” their act had stirred up a generation just as desperate as they were—for intimacy, for truth, for something, anything, different—with pace frightening enough to draw concern from the government. In a Village Voice readership poll conducted in 1968, their debut album was voted second only to the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band; that same year, keyboardist Ray Manzarek was voted rock’s third best musician, trailing only Eric Clapton and Ravi Shankar.

“Hundreds of wooden folding chairs were hurled at the cops. Hundreds of teenagers were bleeding.”

But it was Jim Morrison, a charismatic sex symbol with urgent poetry and primal energy, who catapulted the Doors from musical virtuosos to a volatile, transcendent cultural force. He was a writer long before he had been a musician, growing up with ambitions to be a poet that carried well into his career as a frontman. In a sense, his performance was less a matter of music, and more a matter of using the music, and the band, as a vehicle to platform his literature. Shortly before the Singer Bowl performance, he had to be talked out of quitting the group to pursue the literary career he always sought. “It was Morrison who had described The Doors as ‘erotic politicians,’” Joan Didion wrote of the Doors in her essay collection The White Album. “It was Morrison who had defined the group’s interests as ‘anything about revolt, disorder, chaos, about activity that appears to have no meaning.’ It was Morrison who got arrested in Miami in December of 1967 for giving an ‘indecent’ performance. It was Morrison who wrote most of The Doors’ lyrics, the peculiar character of which was to reflect either an ambiguous paranoia or a quite unambiguous insistence upon the love-death as the ultimate high.”

That night in Queens, Morrison mounted the stage with a pair of officers latched onto either arm, almost as if he were preemptively being led away in handcuffs. On the platform, before any of the band members had arrived, was a brawny assemblage of about twenty cops, all trying their best to create a moving, living, fan-proof forcefield. It looked like the ring had been host to a last-minute referee overbooking, or that maybe, perhaps, this bout in particular had deadlier stakes than the others on that day’s match card. (For what it’s worth: the earlier match on today’s card was an opening set by The Who, who had leapt at the opportunity to curry favor with American audiences via the Doors’ co-sign.) “Five to one, baby / one to five,” Morrison rasped, belting the obscure-yet-oddly-moving lyrics to a track from the Doors’ then-latest album, Waiting For the Sun. “No one here gets out alive.”

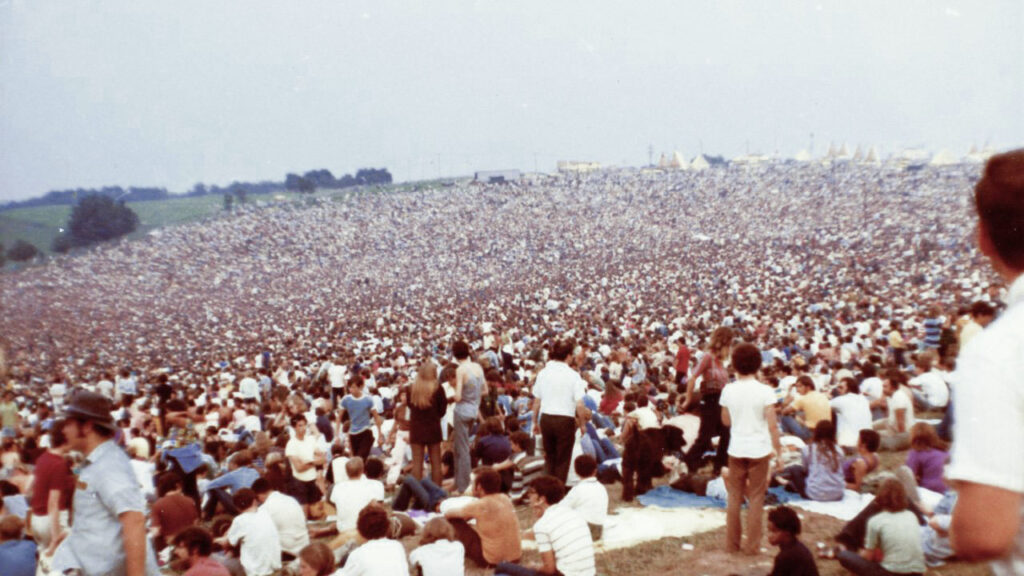

As true as these sentiments are for any revolution—either the past dies, or you do—its undertones wasted little time growing frighteningly literal. It’s worth noting that for this era of rock music, open-air concerts had yet to be completely figured out. With no industry standards to be followed—hence the center-stage platform, the boxing-informed entrance, the unprepared cops—and a growing demand for them to be established on the fly, live shows constantly teetered along the brink of healthy energy and catastrophic dystopia. At the Altamont Festival in 1969, a teenager was stabbed to death by the Hells Angels motorcycle gang after a stage-security argument grew violent; perhaps most famously, beneath Woodstock ‘69’s promise for “Peace & Love” existed far grimmer realities brought about by poor planning and underpreparedness. At the Singer Bowl, Morrison sang more to the backs of police officers than he did to people. The few youths that did peek out through the cracks were violently thrown back into the darkness from whence they came. “No one could see,” Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugarman wrote in No One Here Gets Out Alive, Morrison’s 1980 biography. “Hundreds of wooden folding chairs were hurled at the cops. Hundreds of teenagers were bleeding.”

The Doors got their name from The Doors of Perception, a famed treatise by the speculative fiction writer Aldous Huxley in which he—like countless other curious souls in his era—jotted the results of various experiments with psychedelics. Morrison was obsessed with the book, and perhaps his obsession echoed that of his young-and-confused worshippers: not a concern with drugs specifically, but the broader sentiment of seeing beyond something, doing away with an old system, forcing one’s way through a threshold. Much of Morrison’s lyricism hinged on a similar militant escapist quality, typically foregrounded by romance, but buoyed by a certain urgency for progressive relocation. “Break on through to the other side,” he goads in one of the most enduring Doors singles; in perhaps the most popular Doors song to date, he’s a romanticist first, but a brazen generational opportunist between the lines: “You know that I would be a liar,” he croons to an unnamed love interest, “If I was to say to you / Girl, we couldn’t get much higher.”

“But then, that night and in those days what came out of that stage was not nostalgia but new, raw, powerful music that didn’t wait for you. It came for you, grabbed you, and demanded you listen.

The interesting thing about the scene at the Singer Bowl, with these transgressive undertones in mind, is the prospect of youth willing to break walls to the extent that they, themselves, were broken. More often than not, the most enduring musical movements tend to be the ones with the most vague goals: fueling grunge’s takeover was a desire for something culturally different; undergirding generative East-West hip-hop competition was an arms race for something sonically different; cementing Morrison’s lofty rhetoric was a generationally-felt gravitation towards something existentially, socially, politically, different. A consistent fixture across each of these movements, each of these outgrowths of desperation for difference, is, oddly enough, bloodied teenagers. In grainy post-concert VHS footage from the Singer Bowl show, Jim Morrison is seen backstage, seated next to a young girl with splotches from a fresh head gash scattered across her white dress. As the frustrated voices of matronly women and police officers attempt to piece together what happened, Morrison speaks softly to the injured reveler, assuring that she’d been an “innocent bystander”—“that became a victim,” she interjects, somewhat annoyedly. Like the confusing lyrics of “One To Five,” the title of his biography, and the fledgling live-music universe it all rested upon, the moment seems confirmative of a deep-seated truth: when the time comes for revolution, no one truly does get out alive.

But some survive long enough to tell the tale. A 2020 YouTube video compiled footage from the Singer Bowl show, and two other raucous 1968 Doors concerts from Cleveland and Philadelphia; the top commenter was a man who claimed to have been to the New York event. “When you listen to the songs now you’ve probably heard them a thousand times,” he wrote. “But then, that night and in those days what came out of that stage was not nostalgia but new, raw, powerful music that didn’t wait for you. It came for you, grabbed you, and demanded you listen.

“My remembrance of the final part of the show was Jim Morrison saying something like ‘the cops want to shut us down but we don’t want to go,’” he continued, further down. (It is a very long comment.) “With Jim taunting the crowd with ‘you don’t want us to go do you? They’re telling us to go but we don’t want to go’. Our seats were higher on the side but we could just see the police on the stage trying to get Jim off and then there was just a blur of parts of wooden police barricade pieces flying through the air. That was followed by that feeling you get when you realize you are caught up in something that came on fast, you didn’t want and your nerves inside are reflecting that.”

Perhaps the feeling he’s describing, and Morrison was invoking, is one that has crept its way back into music discourse, most concentratedly in stan culture. “Collective psychosis,” specifically the “psychosis” part, suggests a blurring between the real and the imagined, somewhat in similar vein to the psychedelics that undergirded the hippie generation’s sacred live-music rituals. But as much as these things may have been enhanced with the help of imagination, it can’t be denied that the root causes—visceral needs for intimacy, freedom, something different—were far from made-up. It’s interesting to see early concerts, quasi-movements rife with bloodied teenagers and boxing aesthetics, as exercises in both radical presence and radical absence: escapists escaped among other escapists, but in those hours of physical punishment, they were, in a weird way, as present as they would ever be.

💧💧💧

“It’s exciting, but it’s not music. It’s mass hysteria.”

A “collective” term that predates collective psychosis, if not just culturally, is “collective effervescence”: the idea that a community of people may convene to experience the same thought while participating in the same action. The concept was coined by the French sociologist Émile Durkheim in the early 20th Century, as a basis for his theory on religion. A common talking point among anti-queer conservatives is that everyone has a “religion,” whether conventional or not—and that the need for “religion,” or something to viscerally identify with, is the basis for anything not heterosexual—but the argument, in large part, overlooks that religion is a formality long before it’s a bodily impulse. Retrospectively speaking, collective effervescence may have ruled in the Doors’ late-60s reign because their urgent collective impulses sprang from equally-urgent collective contexts. For a young America freshly beginning to realize that the government was capable of misleading them, that truth was sometimes punishable by death, that they could be killed in wars they didn’t believe in, the Doors’ music—and the brazen man whose voice carried it—represented a sort of novel, now-or-never call to action. But what this “action” entailed, exactly, was unclear, and left to be resolved among people, usually by the thousand, who were (1) equally confused, and (2) equally ready to bleed if it meant figuring it out. “-The sheer excitement of the event, the mass of people mingling together, generates a kind of electricity, and it has to do with music,” Morrison told Rolling Stone in a 1969 interview. “It’s exciting, but it’s not music. It’s mass hysteria.”

By the time Morrison died in 1971, it felt less like he was a curator of collective mania, and more like he was a victim of it. For what seemed like his entire career, he wrestled with dreams of being recognized as a writer first and a musician second, going increasingly desperate lengths to escape his sonic predicament. He self-published ambitious poetry books under the name “James Douglas Morrison”; his first and only antemortem trade publication was The Lords and the New Creatures, a dense volume that combined two of his earliest attempts at putting together poetry manuscripts. Some of his literary writing, contrary to popular sentiments, carried flashes of frenzied genius, not too far off from the visionary lyricism that made the Doors’ music so infectious. “Let’s re-create the world,” he urged, no different from urges he made on-stage, in a poem called “The Opening of the Trunk.” “The palace of conception is burning / Look. See it burn / Bask in the warm hot coals.”

As his writing continued to fail commercially, and means of escaping his rock-star image grew few, he slipped further into alcoholism, which damaged both his body and his voice—two of the most vital factors to his being a messenger for the generation that deified him. (In No One Here Gets Out Alive, it is written that when a fan pointed out to him that he was “getting fat,” he enrolled in a nutritional self-help program; the membership was abandoned within weeks.) Though the circumstances surrounding his death are unclear, it feels as if it was both an act of ultimate rebellion, and ultimate entrapment: with the walls closing in on his dreams to transcend, his breaking-through was both a matter of graduating beyond a restrictive plane, but also being a casualty of it. Like the bloodied girl at the Singer Bowl, he, too, could not be an innocent bystander in his own revolution.

“But when we once again return to an America that feels as if it’s going to break in half—and with an election slated for next year, this day could come soon—it may not end up being productive, either, for live music to function with no function, to be an empty ritual.”

Retrospectively speaking, it seems that modern concerts suffer from a similar inability to outgrow their foundational ethos. What separates now from then, perhaps, was that in Morrison’s era, it had been the first time America felt as if it would break in half. Live music seemed to be a commonly-felt bodily impulse; it was the satisfaction, by physical exertion and cathartic violence, of a need for answers—even if they were temporary—in a wilderness that did its best to overwrite them. Half a century removed from the U.S’ first days with concerts as hubs for spiritual chaos, it feels visible that shows are more of a religious entity, or formality, than the product of a shared visceral desperation. People go to concerts, it seems, for the same reasons they might go to church: they support the artist in theory, whether man or God, but little else. Both religion and concert-going hold space for devout followers and too-cool ones, the ones who spasm through all the lyrics because they can’t help themselves, and the ones who lurk on the outskirts, wary of attracting too much attention. In the Doors’ heyday, everyone who attended a concert was, by necessity, in the former category. As concert culture evolves, it seems that more and more room is allocated to the latter.

Maybe it’s because we haven’t felt like America was going to break—or, if we did, we were somewhat assured that the fracture wouldn’t be final. Three years ago, in the most recent moment of breakage comparable to Morrison’s, concerts were, of course, replaced by virtual alternatives: Verzuz battles, Instagram live-streams, new apps, new workarounds. Both then, and in the following year’s long-prophesied return to real venues, the sentiment was less centered on desperation, and more rooted in a sort of prosperity gospel. This was only temporary, it felt like everyone was saying; if we weren’t out of the mud, we would be soon enough. The first sold-out show at Madison Square Garden, after the pandemic, was headlined by the Foo Fighters, who opened with “Times Like These”—fittingly less a song about desperation than wistful reflection, or maybe triumph. “Fans were packed together,” a New York Times reviewer wrote. “A sudden arm gesture could send a beer flying. Strangers hugged and high-fived. They bumped into each other in the busy concourse. They punched the air, swung their hair and danced, twisting and swaying at their seats in a state of high-decibel music-induced bliss.”

Free from pandemic-era confines, and back in semi-stasis, it’s worth questioning what the purpose of live music is, and why exactly we attend the concerts we do. In an America not at immediate risk of breaking in half, perhaps it isn’t entirely necessary for a concert to be a forum for deep-seated sociopolitical frustrations. But when we once again return to an America that feels as if it’s going to break in half—and with an election slated for next year, this day could come soon—it may not end up being productive, either, for live music to function with no function, to be an empty ritual. In one of the most oft-recycled images from A$AP Rocky’s Testing phase, a pre-pandemic album cycle rife with crash dummy imagery, vehicular dramatics, and spiritual talk about moshing, the rapper poses alongside a bleeding fan, both men grinning. As far as concert safety goes, the photo definitely has its nuances—especially after similar intentions resulted in catastrophe at Travis Scott’s Astroworld festival—but in a lineage of fans who fought through Doors concerts 50 years ago, it hinges on a similar line of questioning. Are you willing to bleed for it? And if not, is that necessarily a bad thing?

This past weekend at the third edition of Young World, an annual one-day festival hosted by the Brooklyn rapper MIKE, there came a point where it rained. The grassy space backstage was packed with energetic associates and fellow artists; every now and then, one would creep up to a makeshift peeping-hole between the slightly-elevated platform and a set of covered instruments, peering out at the sea of bouncing umbrellas that lay on the other side. Midway through MIKE’s set, Earl Sweatshirt, a friend of his, leapt up as if he couldn’t stand being dormant any longer. “Nah, stop playing with it,” he said, jolting up the metal steps; a roar emerged from the sea of umbrellas, and a steady line of artists and friends from backstage followed suit, trailing behind one another up the mini-staircase.

Freshly removed from a ten-minute lightning break, and with a forcefield of support spilling out from behind him—a polar opposite from the forcefield of police that barricaded Morrison—MIKE lofted an echoey address to the sea of damp afros that lay ahead of him. “No rain can stop this,” his voice boomed; “no lightning can stop this. No thunder can stop this.” A term he quotes often is “Burning Desire,” and before he lurched into his next selection, he asked the dripping-wet audience whether they had one. There was a resounding affirmative, and in that moment, with “yes” sounding like one uniform holler, it was interesting to imagine how many individual yes’s existed within it. Regardless of whether concerts speak to something occuring on a cultural plane, address deep-seated personal nerves, or attempt to mend something on the verge of breaking in half, they will perennially represent a place of intersection—between hundreds of people, hundreds of ideas, hundreds of sounds. None of them get out alive. Sometimes, that’s all they need to live.