🌐🌐🌐

Newer Art, Newer Money

As we sit on the brink of mass newness as a society, lessons from the 1984 Neo-Expressionist Movement remain a silent shadow over looming artistic revolution.

SAMUEL HYLAND

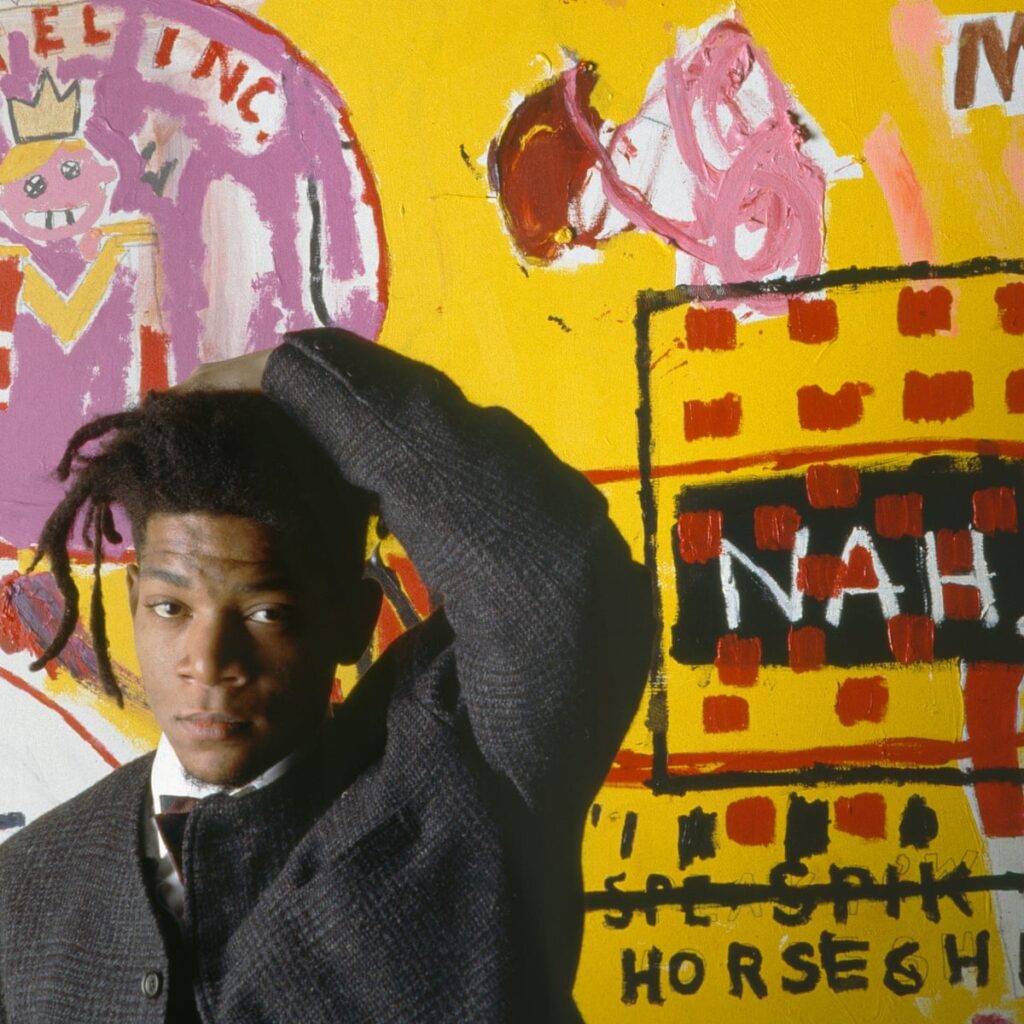

Jean-Michel Basquiat was a regular at Mr. Chow’s. On one of several days that the journalist Cathleen McGuigan shadowed him for an iconic New York Times Magazine cover story in 1984, he gorged exquisite dishes (steaming mushrooms & abalone were on the menu tonight) in the Midtown Manhattan eatery, talking early-stages graffiti escapades with Keith Haring between swigs of a Kir Royale, whilst Andy Warhol and Nick Rhodes chopped it up at a table nearby. A major factor in Basquiat being a regular was that the owners, Michael and Tina Chow, loved his artwork – so much so, that they bought it for restaurant ownership, then commissioned him to paint their portraits. Every night that he dined at Mr. Chow’s, he dined both surrounded, and tenably paid for, by his own creations.

In terms of both celebrity stature and financial prowess, such scenery was a far cry from the Cedar Tavern, the longstanding social headquarters of a school of New York-centric contemporary artists that ceased to exist decades before the likes of Basquiat and Haring eased into the zeitgeist. These were figures like Frank Kline, Jackson Pollock, and William De Kooning, who pioneered a vigorous abstract expressionist movement in the city throughout the 1940s and 50s. Outside of art, the champions of the crusade en masse led notably muted lifestyles. Rather than seek to be recognized in the same hefty spotlights that their works attracted, they lived ostensibly on the edge of celebrity; the artwork was its own entity, the name it bore was not much more than a signature on the corner (at least not yet). The Cedar Tavern epitomized, in many ways, the creative culture that this bred. A grubby restaurant/bar on the eastern edge of Greenwich Village, it was flocked by societal dropouts for its cheap drinks and weekly arts salons. Because of its location away from the glitzy draws of Times Square – its home community was downmarket as a result of several welfare and single-occupancy hotels in the neighboring area – the only consistent patrons were pigeonholed into a narrow categorical selection of abstract artists, writers, and other eclectically-disciplined creatives who worked in mediums yet to be accepted into the mainstream.

“Some painters, including myself, do not care what chair they are sitting on.…They do not want to ‘sit in style,’” De Kooning explained during a 1951 lecture at the Museum of Modern Art. The lecture, delivered at the height of its accompanying movement, was entitled What Abstract Art Means to Me. “Those artists do not want to conform,” he went on. “They only want to be inspired.” Internal spark – rather than external flourish – was the common driving objective behind abstract expressionism’s most dynamic figures. Inspiration was the eruption. Anything that manifested itself onto the canvas was no more than residue, every hardened brushstroke fossilized debris.

Thirty years later, though, onto the scene came upstart soon-to-be moguls like Basquiat. And although it can be argued with evidence that he, too, was in it for the art and not the money – by appearance alone, it couldn’t possibly seem like it to anyone having emerged from De Kooning’s hyper-reserved Cedar Tavern era.

What was different about Basquiat is a construct wholly epitomized in the four-word headline to the aforementioned 1984 New York Times Magazine cover story: “New Art, New Money.” The art was new in that, after a decades-long creative lull, it picked up where abstract expressionism left off. It was a shift dubbed “Neo-Expressionism” by critics and dealers. Many collectors, Mcguigan wrote, had not experienced competitive bidding for art that was just as visually thrilling as it was valuable since the 1960s. One collector included in the essay, Eugene Schwartz, said of the moment he saw a painting by the artist Julian Schnabel in a dealer’s gallery: ”It brought us (Schwartz and his wife) from the 60’s to the 80’s in about 14 seconds’ – adding that since purchasing it, he started collecting “compulsively.”

“It was not a matter of challenging the viewer to make meaning; it was a matter of challenging the viewer with the meaning itself.“

But, perhaps to an even greater extent, the money was reborn anew as well. At the time that McGuigan initially met with Basquiat, he was 24 years old, and the general selling price of his individual paintings ranged from $10,000 to $25,000. At the reopening of the Museum of Modern Art in May of 1984, a self-portrait of his went on display as part of the night’s festivities, without the monetary element being nearly as much of a factor. Then, not too long afterward, a two-year-old painting of his – one that initially sold for $4,000 – was purchased off of the auction block at Christie’s Spring Sale for $20,900. The money ballooned because the market had been asleep. Much of the artwork that dominated buyer/seller circles between the 60s and 80s was conceptually challenging, increasingly stale excess from decades long gone, with consumer interest depreciating just as swiftly as the creative quality seemed to itself. Now that there existed a sudden influx of new inspiration, new authenticity, and newly sourced approach, the money hastened to be there to match the movement. In an instant, opening their wallets wider than ever before were big-name gallery owners, art dealers, tycoon business owners, and esteemed museums themselves. The elite had re-entered the conversation.

Whereas in the past, such a course of events often meant one-sided, closed-door relationships between wealthy consumer and relatively isolated producer, though, the 1980s Neo-Expressionist movement allowed a tertiary element into the cycle: the people. It helps to consider it in terms of the business slogan: “for us, by us.” On the “by us” end of the spectrum, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring were disgruntled teenagers long before they were multi-million dollar gallery darlings. Before their spray-painted scrawlings were called “high art,” they were called “vandalism.” As for Basquiat, he dropped out of school on two occasions (one of them coming after he threw a cream pie in his principal’s face) before he adopted a lifestyle of taking heavy drugs in Washington Square Park whilst living couch-to-couch in various friends’ houses, and imposing art upon everyday objects because he couldn’t afford professional supplies. Haring, too, was arrested on countless separate occasions for turning empty subway cars into expansive canvases for intricate chalk drawings of dancing adults, crawling babies, and barking dogs. Their work spoke from a chasmal void, authentic chiefly because they were operating without any ulterior aspiration of emerging from it.

The “for us” portion of the slogan played out in what became a drastically altered demographical makeup of high art audiences. In 1982, following a highly reported-upon split from his former suitor, the Annina Nosei Gallery, Basquiat lived reclusively in a hermit-esque SoHo apartment. There, he worked on a vast array of new paintings entirely outside of the public eye – a lengthy period that culminated in a widely-anticipated one-man show of his at the Fun Gallery, which was run by the former underground movie actress Patti Astor, and her husband Bill Sterling. “’I liked that show the best,” said Bruno Bischofberger, a Swedish dealer and gallery owner who took an early liking to Basquiat’s output. ”The work was very rough, not easy, but likable. It was subtle and not too chic. The opening was great, too. It drew young blacks and Puerto Ricans, along with limousines from uptown.”

Aside from familiarity on the part of the local crowd, what made it so that Basquiat’s work could attract revelers from such opposite walks of life was, before anything else, its duality: It was almost exaggeratedly simple, even childlike at some points – but, on the same canvases that bore archaically sketched dinosaurs, juvenile crowns, and daycare-reminiscent etchings, there were menacing masks, jarring eyes, and threateningly unapologetic sexual displays. Unlike the legion of monotone art content that put the market to sleep before his ascent, Jean-Michel Basquiat did not create as much for the sake of complexity, as he did for the sake of firebrand truth. His pieces told stories of primitive nature played out in the marshes of the jungle, on to the streets of New York City, then onward to the confines of his very mind. It was not a matter of challenging the viewer to make meaning; it was a matter of challenging the viewer with the meaning itself. ”Basquiat proceeds by disjunction – that is, by making marks that seem quite unrelated, but that turn out to get on very well together,” then-New York Times chief art critic John Russell wrote of his visual approach. What was ”remarkable,” added Vivien Raynor, also of The Times, ”(was) the educated quality of Basquiat’s line and the stateliness of his compositions, both of which bespeak a formal training that, in fact, he never had.”

“Visual art has transcended the canvas and made its way onto the screen. Big money has graduated from the bank and matriculated itself into the Stock Market. Just like criminal street art found its way out of the ghettos of inner-city New York, and onto the walls of the socioeconomic elite, hip-hop fashion is gradually finding its way out of the thrift store, and into the collections of Europe’s most prolific designers. The dynamic doesn’t change at all – only the medium.”

Where such economically ambiguous producer/consumer relationships fell short, yet, were in the places where the aforementioned void – where figures like Basquiat and Haring sourced their early creative work – became a portal. Creating from the void guaranteed immunity from the restraints of criticism, money, and fame. As the elite became more and more involved, the void opened wider and wider, and the dealers, gallery owners, and moguls manning the controls were made increasingly able to stick their hands in and drag out the contents as they pleased.

Basquiat’s first, and perhaps most highly publicized brush-up with such a dynamic came when he accepted an artist-in-residency offer from the above-mentioned Annina Nosei Gallery in 1981. Prior, he worked exclusively from a tiny apartment in the Lower East Side, the only other people to ever occupy the space at a time being one of his several girlfriends (a list that, at one point, included a young Madonna). One of few outsiders to witness him at work in that setting was the art critic Jeffrey Deitch. Among the first things he witnessed upon setting foot in the studio were a battered refrigerator covered from top to bottom with scrawlings, drawings on all sorts of cheap paper, and omnipresent footprint smudges. “It was one of the most astounding art objects I had ever seen,” he recounted some time afterward. He continued working as if the visitors were interrupting him (which, understanding Basquiat, they very likely were). Deitch wound up paying $250 in cash for five of his drawings. It was likely Basquiat’s first sale – a friend of his had to remind him to sign the pieces.

The arguably downward publicity spiral that commenced with Nosei’s gallery was, by several measures, seemingly a growth from the seeds sown by Deitch’s apartment visit. Annina Nosei took Basquiat in because she realized that he needed a place (and a consistent means) to eat and sleep; she allowed him the expansive basement area of the complex to work to whatever capacity he pleased. The issue arose when publicity crept further into the picture. On an almost-daily basis, wealthy observers were paraded down to the lower level to witness the spectacle that was the wizardous, trending, top-tier creative. “Basquiat,” Deitch wrote of him within this period, “is likened to the wild boy raised by wolves, corralled into Annina (Nosei)’s basement and given nice clean canvases to work on instead of anonymous walls. A child of the streets gawked at by the intelligentsia.” Basquiat was becoming a prop. To him, the sacred urban tales he reimagined on his canvases were living testaments to his being. To the consumers, they were colorful, collectible tokens, relics from the depths of an inner-city lifestyle that was too repulsive to explore beyond the television screen.

The breaking point came when he was asked to produce eight paintings within a week for an upcoming show in Europe (“It was like a sick factory there; I hated it,” he said to McGuigan). In a defiant flash that encompassed his infamous temperamental nature, he returned to the basement one evening, and wreaked havoc on ten unfinished paintings: slashing them, folding them, jumping on them, and dousing them with paint before quitting the signage for good and venturing on to a lengthy period of heightened hostility toward society at large.

Even at this point, high-level dealers and collectors continued to unrelentingly seek after his hand in business. Without fail, and with increasing frequency over time, they would come knocking on the door of his apartment, gazing around as they did when he was confined to Nosei’s basement, and fruitlessly attempting to negotiate possible partnerships or otherwise business ventures. In one case, a dealer who took note of his knack for health food visited his loft with a large jar of fruits and nuts. Once inside, she attempted to woo Basquiat into a deal by claiming that the black man in the driver’s seat of her car – her personal chauffeur – was actually someone who worked with her in her gallery. As she walked out of the front door in flustered defeat, he leaned out of a window and dumped the contents of the jar onto her head.

“But what the Neo-Expressionist movement lacked in common with the others was, when all was said and done, the side that came out on top. One party wound up dead of a heroin overdose. The other party wound up with a vast collection ready to be converted into cash at any given moment –“

No matter his resistance to extraneous ownership, though, living as the chief pioneer of an artist-celebrity archetype New York had never seen also bred a degree of mental bondage. The art and its accompanying value were at new levels, but with these things also came the criticism. The Neo-Expressionist movement was not received well by everyone. “The new expressionism tends to be a generalized Angst,” mused Thomas Lawson, a painter and editor of Real Life Magazine, a small-circulation artists’ journal. ”You can’t tell what the artist is reacting to. It’s not very reflective.”

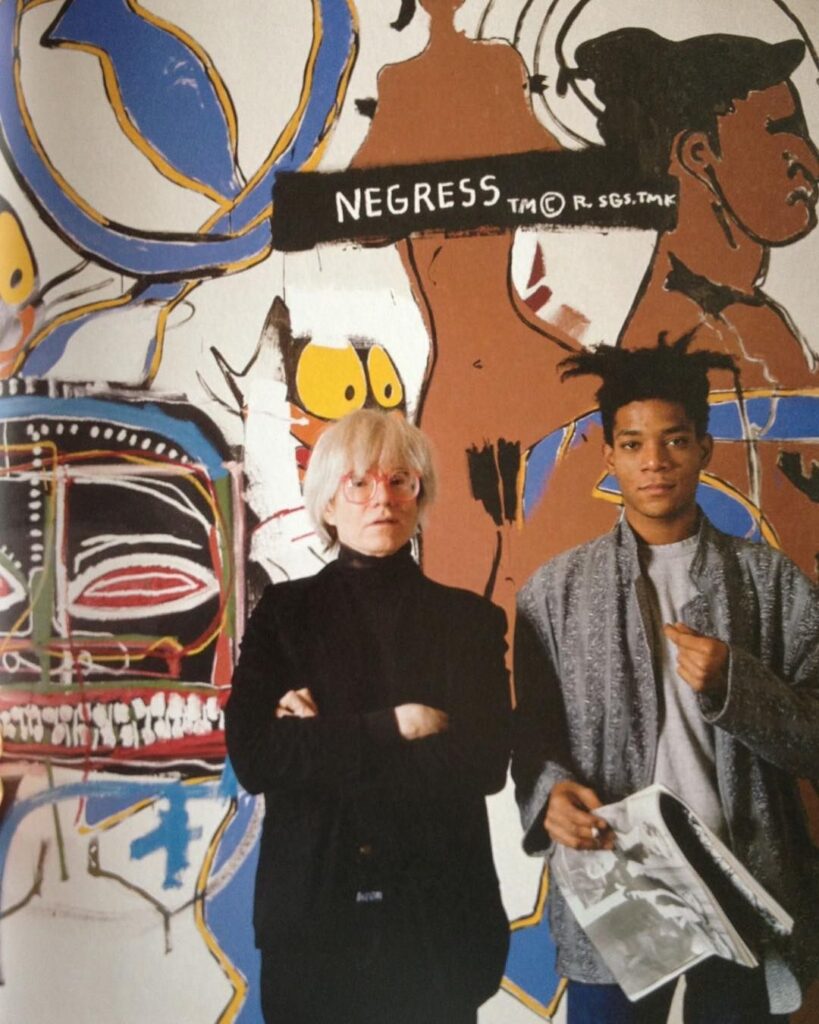

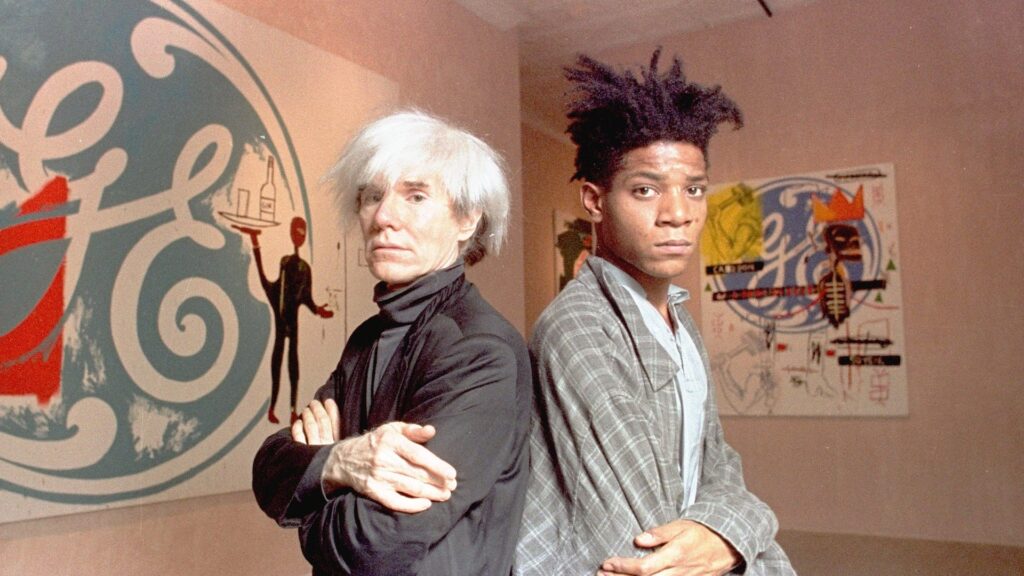

As for Basquiat himself, as the stakes grew steeper in his case, the strict box of expression that satisfied his audience gradually closed in around him. In what is likely the most well-documented example of such a dynamic, Basquiat began a synergetic relationship with the prolific New York City art mainstay Andy Warhol in 1982. For a period of time that stretched to the latter portion of Basquiat’s career, the two exchanged portraits of the other, advice from opposite generations of the bustling scene, and collaborations on ambitious undertakings. Basquiat had tapped into a creative direction that both felt, and looked, tangibly free; there was a level of refreshment that began to contrast with the darker undertones of his earliest works. “I think I’m more economical now,” he said, raving about his newfound approach. “Every line means something.”

The critics at the subsequent gallery showings, however, were not as impressed. “They’re fresh out of the Factory (Warhol’s longtime New York studio),” wrote Nicholas A. Moufarrege in a less-than-favorable Flash Art review. ”These new paintings are too charming, they lack the nitty-gritty hip-hop and the jagged power that his last New York show at the Fun Gallery emanated.”

The initial reason for which affluent art collectors sought to jump onto the Neo-Expressionist movement at its apex, besides renewal of artistic quality, was an overarching desire to ride the wave before they could be engulfed by it. As it progressed, though, and their position atop the wave became increasingly stable, the motive changed. Why ride the wave when you have the power to control it?

Nearly every significant artistic movement prior to this one had fought against a common entity of oppressive exclusivity. The European Renaissance, blueprint en masse for grassroots cultural demonstrations since, successfully waged war against an omnipresence of Catholic Christianity in the ruins of Middle-Ages Rome. The Symbolists Movement of the 20th Century, too, manually repealed a growing dictum in contemporary art that anointed meaning solely decipherable within demonstrated skill. At surface-level, the circumstances surrounding the Neo-Expressionist movement seem to follow suit: there are lesser-represented creatives brought up to elite levels once-unattainable; the typical gallery opening consists of lifestyles both rich and poor meshing within one-another in appreciation for a common spectacle; criminal vandalism becomes prized memorabilia for immediate auctioning and collection. But what the Neo-Expressionist movement lacked in common with the others was, when all was said and done, the side that came out on top. One party wound up dead of a heroin overdose. The other party wound up with a vast collection ready to be converted into cash at any given moment – just last week, news of a manually deconstructed Basquiat sketch being put on the market as an NFT made international headlines. Although the sale eventually wound up being cancelled, one is forced to wonder: how much of the legacy belongs to the artist, and how much of it belongs to anyone who can afford it?

Art is not as essential a component of the New York City cultural zeitgeist as it was four decades ago, but just as it did then, without a doubt, the art and the money alike are only getting newer. Visual art has transcended the canvas and made its way onto the screen. Big money has graduated from the bank and matriculated itself into the Stock Market. Just like criminal street art found its way out of the ghettos of inner-city New York, and onto the walls of the socioeconomic elite, hip-hop fashion is gradually finding its way out of the thrift store, and into the collections of Europe’s most prolific designers. The dynamic doesn’t change at all – only the medium.

And there is nothing we can do about it. For every talent that emanates from the void, there will always be a force from above relentlessly trying to drag it out. For every community of which art – whether written, visual, sonic, et. al – is a hollowed reflection, there will always be a people for whom it is a coveted relic. There is no such thing as untampered originality, and if there is, given a measure of exposure, it will quickly be rendered a reflection of what used to be.

“- just last week, news of a manually deconstructed Basquiat sketch being put on the market as an NFT made international headlines. Although the sale eventually wound up being cancelled, one is forced to wonder: how much of the legacy actually belongs to the artist?“

Basquiat’s prime impulse for making art was not money, nor fame, but boredom. “There’s really nothing else to do in life, except flirt with girls,” he tells McGuigan as the cover story comes to a close. “If I’m away from painting for a week, I get bored.”

The mentality was one that forced Basquiat to work relatively feverishly. Over his short-lived career, he produced over 600 paintings and 1,500 drawings, all of which were meant to serve his own creative purposes.

McGuigan’s cover story – published four years before his death – came to a close with an eerie nod to their collective fate.

“The artist, who does not profit from resales, may be off at work in a new direction,” she started. “But even the paintings he said goodbye to long ago keep going round and round in today’s heady art world.”