In alt-pop’s annals, a firebrand old-world generation wages a losing battle against a silent victor.

💐HOW LATE IS TOO LATE?💐

SAMUEL HYLAND

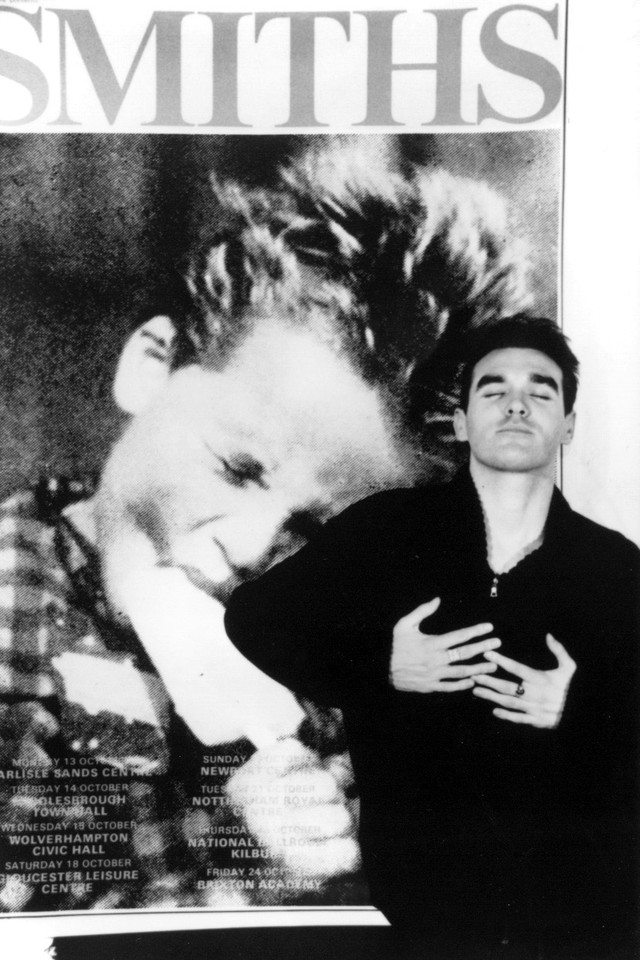

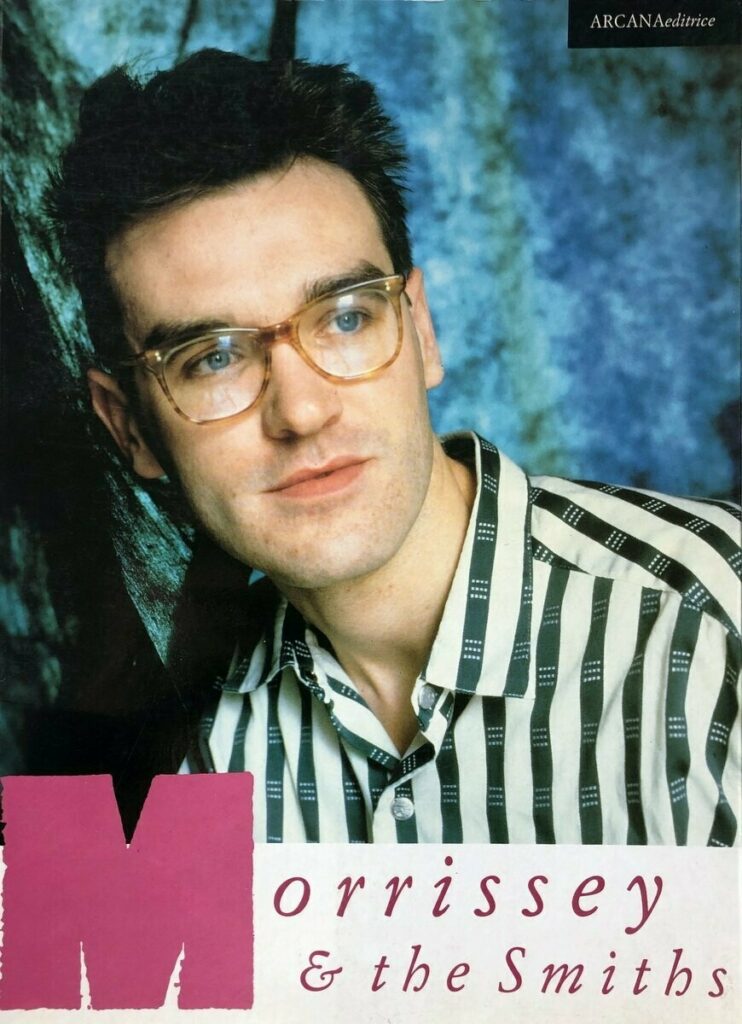

A recent New Yorker review of Lana Del Rey’s latest full-length release began with the statement that she was “a bit of a silly goose.” The same week, amid buzz surrounding the album’s mixed reception, a viral tweet challenged users to think up a Lana Del Rey analog, but for men; two of the most agreed-upon responses were Father John Misty, the longtime American indie rock fixture, and Steven Patrick Morrissey, the controversial Smiths ex-frontman who goes mononymously, and often seems to think mononymously — one closed-minded thought at a time — too. Morrissey was a silly goose before he was a problematic one, and earned both mass acclaim, and mass intrigue, for the baritone incel gospel he crooned over Johnny Marr’s go-lucky guitar riffage through much of the 1980s. Little was known about his sex life, but as much as it was all he ever really sang about, it rarely registered like he wanted people to know its merits in the first place. By some accounts, he was celibate. By others, he was a hopeless romantic who had sexual desires, but didn’t know exactly what to do with them. In the second and final verse of “Pretty Girls Make Graves,” a brooding number from the Smiths’ eponymous 1984 debut album, Morrissey bellows, half-desperate and half-detached, “I’ve lost my faith in womanhood / I’ve lost my faith in womanhood / I’ve lost my faith.” For both the question of his sexual habits, and the question of his character at-large, the career-defining non-sequitur “I’ve lost my faith” was at once infinitely telling, and infinitely challenging. It was obvious that there weren’t many things he believed in. The question was whether he believed in anything at all.

Decades later, from the little evidence currently available, the answer is very likely yes: Morrissey, like any other thinking being, can be assumed to stake some sort of belief in at least one thing. But specific details aren’t entirely clear, and in the rare event that he emerges from his cocoon to change this, he either implies belief in something inexcusable — I’ll take “Muslim immigration is a cancer to British heritage” for 400, Alex — or winds up leaving people more confused than they already were. At his climax, much of Morrissey’s approach was centered around an infectious mixture of radiant passion and radiant flamboyance, little-to-none of it seeming to be of any real-life substance. As the bookish-looking frontman of the Smiths, his hopeless-romantic schtick led him to be a de-facto poster-boy for directionless, teenage emotion; much like his coming-of-age audience, he, too, was plagued by a plethora of urges, and a shortage of non-masturbatory outlets. But unlike the dawdling young people he serenaded, most of whom would eventually grow up to find their own respective middle-grounds between hope and hopelessness, he never did stop centering his identity around the extremes. Though Morrissey has gotten older, his rhetoric has failed to follow suit — and every time he pretends this isn’t the case, it only becomes more glaringly obvious. In a 2022 podcast appearance, Red Hot Chili Peppers ex-guitarist Josh Klinghoffer blamed the postponement of his then-forthcoming album on mass ignorance. “I don’t know how much time they spend listening to his [music], thinking that they really know where he’s coming from,” he said. “People just might get offended. I don’t, because I honestly don’t think he’s a malicious person, even if he says stupid shit.” As well-intended as he may be, he’s too confused, and too confusing, for anyone to ever take his word for it.

“When the limelight they once enjoyed moves further away from them, they scream to remind themselves that they’re there; as is the case for their respective forums (Morrissey’s website and Pink’s Twitter account), no one with the power to change anything is listening.”

An oft-quoted Smiths song begs a hopelessly metaphysical question: “How soon is now?” The anthem finds Morrissey in a familiar role — cripplingly-shy romanticist racing against both his own limitations and the clock’s — but today, perhaps, its implications harp less on elusive romance, and more on elusive redemption. An up-to-date rephrasing might instead ask how late is too late, and Morrissey wouldn’t be the only one obscured by the query’s daunting shadow. As alternative music welcomes a more tight-lipped vanguard into its limelight, and filters out the firebrand archetype that once took center-stage, it remains to be decided whether it’s enough for an artist to ask questions, or if they’re responsible for answering them, too. Morrissey’s music asked questions then, but the problem is that, in three decades, it never did stop asking questions. When the music fails to yield something concrete, the most logical course of action is to look at the musician. Look for something concrete in Morrissey, and you’re likely to find concrete ignorance, or a concrete wall — that is, if you find anything concrete at all. For someone whose artistic shtick has long hinged on an outsider sensibility, the music becomes a lot less believable when, in real life, its maker seems hellbent on keeping the world’s outsiders out. At some point near the close of “He Knows I’d Love to See Him,” a wistful deep-cut from his 1990 compilation album Bona Drag, he sings, somewhat prophetically, of a “radical” man who seeks to “turn [the system] on its head by staying in bed.” “I know I do,” he croons in response. You get the sense that he doesn’t plan on doing anything about it, either.

As of right now, the premiere forum for all Morrissey-to-audience communication is a minimalist website, morrisseycentral.com, quietly established by the singer in 2018. Every so often, a cryptic directory tab titled “Messages From Morrissey” hosts periodical musings on topics ranging from global politics to the deaths of cultural figures. Among the most controversial of these was a scathing “open letter” to his former bandmate Johnny Marr — written, somewhat amusingly, in a way that at times feels more like a lovestruck Smiths song than an angry blog post. “You know nothing of my life, my intentions, my thoughts, my feelings,” the letter read, barreling through a request for Marr to stop mentioning his once-colleague in interviews. “Yet you talk as if you were my personal psychiatrist with consistent and uninterrupted access to my instincts. (…) There comes a time when you must take responsibility for your own actions and your own career, with which I wish you good health to enjoy. Just stop using my name as click-bait.” Though the message was obviously directed towards one person in particular, its sentiments feel broadly familiar for what has become Morrissey’s new shtick: self-defense, but an iteration of it that doesn’t necessarily leave his familiar self-pity behind. Ariel Pink, a similar controversy-prone member of the firebrand, old-world vanguard now finding itself on the outskirts of alternative pop, once told CRACK magazine that he felt he was “being interrogated for some crime I didn’t commit.” Pink and Morrissey represent, whether to their knowledge or not, a certain death throes for a bygone generation that — perhaps as a coping mechanism — routinely conflates long-gone adolescence with imminent obsolescence. When the limelight they once enjoyed moves further away from them, they scream to remind themselves that they’re there; as is the case for their respective forums (Morrissey’s website and Pink’s Twitter account), no one with the power to change anything is listening.

Besides his solo work and the Smiths’ back-catalog, one popular means by which young listeners may become familiar with Morrissey is “I Cannot Fucking Wait Til Morrissey Dies,” a digi-core deep-cut from JPEGMAFIA’s 2018 sophomore LP Veteran. (On the track’s artwork, a Wojak-style cartoon of the rapper urinates into Morrissey’s open mouth as he wails into a microphone.) “Morrissey was the main target of that because he made this shirt with James Baldwin on it, and it said, ‘I feel Black on the inside,’” JPEGMAFIA told the music blog Passion of the Weiss upon Veteran’s release. “I was so offended by that not because it said something offensive—I mean it did say something offensive—but it’s the idea of it. He’s so entitled. He thought he could just do that.” Morrissey thinks he can do a lot of things, but much like the outspoken alt-pop generation he represents, when tangible repercussions challenge his intangible musings, much of the shtick fails to live up to humbling realities. “If Morrissey got a problem, he can pull up, straight up,” the rapper continued. “I give no fucks. I will fight Morrissey, bro. I will fistfight him.” As of the writing of this piece, on a webpage rife with parasocial callouts to figures with either no interest, or no ability, to respond, no open letter on morrisseycentral.com has been written in response.

💔💔💔

“If there is one thing in life I’ve observed / it’s that everybody’s got somebody / Oh no, not me / So I’ve changed my plea to guilty / And reason and freedom is a waste / It’s a lot like life.”

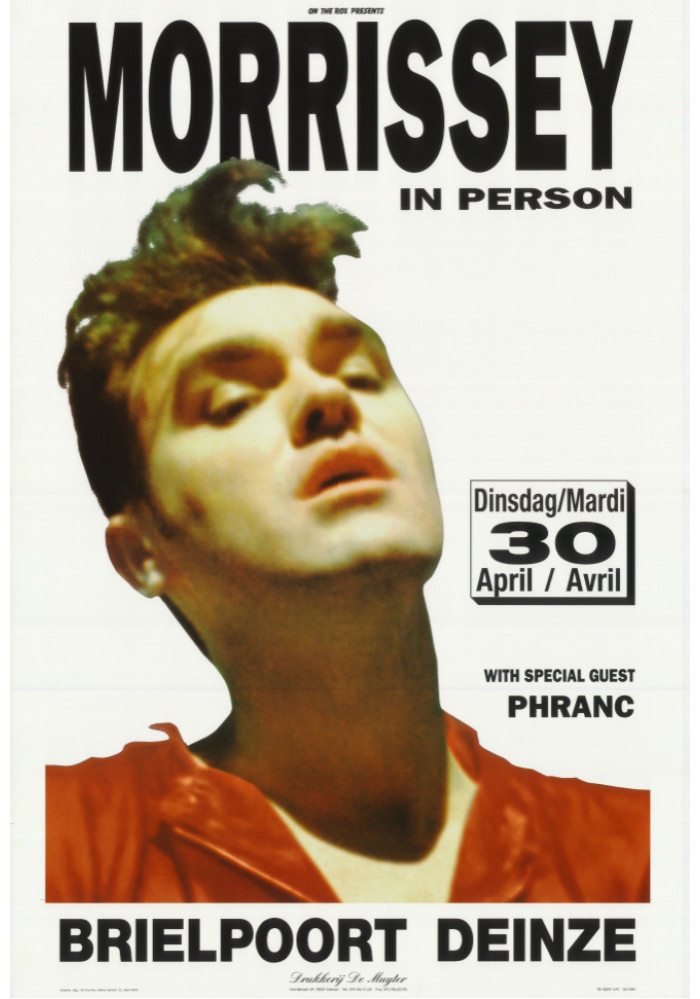

In the past, when Morrissey has made focused attempts at redirecting his image, the efforts have come in packages as ostensibly vapid as his lover-boy theatrics. The Smiths dissolved in 1987 — in large part due to his musical stubbornness and Johnny Marr’s frustration with it — one year after which, donning a new hyper-masculine shtick, the group’s once-bookish lead-man launched a solo career that seemed, somewhat, to have always been sitting somewhere in the back of his head. From the covers of his albums to the attire he donned on-stage, noticeable measures were taken towards the curation of a novel, take-me-seriously-goddammit sensibility. On the sleeve of 1992’s Your Arsenal, his open cardigan gives way to a chiseled six-pack; 2004’s You Are the Quarry sees him tote a machine gun behind a deadpan glare and a crisp business suit. Interestingly enough, in retrospect, it registers that no amount of visual gesturing served to stand in for the sense that, perhaps, he hadn’t really changed that much at all. On “Suedehead,” one of his first solo hits, he addresses an unnamed love interest who won’t leave him alone even though it makes things more difficult. “You had to sneak into my room just to read my diary,” he sings, fielding an interesting push-and-pull between his masculine baritone and pre-pubescent subject matter. “Oh, but I’m so very sickened / Oh, I am so sickened now.” Much like his parting words in “Pretty Girls Make Graves,” here, too, there is a hint towards some sort of grand loss — whether of faith, or of wellness — but no indication of its premises, nor the extent at which it ought to be believed. In the gap between his intentions and his impact, ambiguity reigns, and over decades of zero answers, much of it has festered into doubt.

Self-reinvention is a difficult game to play, but in an era increasingly split between lives lived outside and lives lived online, it may just be more marketable, and necessary, than when Morrissey first stumbled along its tightrope himself. Much of alt-pop’s modern-day appeal nests itself in world-building, the creation of surrounding lore often as encompassing as the music it serves to contextualize. The genre’s current heroes, unlike the outspoken vanguard represented by the Smiths ex-frontman and his contemporaries, thrive largely on tight-lipped approaches that dare fans to fill in the gaps, rather than opt to spoil the answers — and their reputations — for themselves. When this is the case, as seems to be continually proven, a certain level of leeway exists that rarely does for those who have historically operated as both their own mouthpieces and apologists. As of the writing of this piece, the most recent new-world alt-pop acts to emerge from self-imposed cocoons have been Frank Ocean, the reclusive R&B figurehead, and Jai Paul, the mysterious British innovator who disappeared just as quickly as he arrived over a decade ago. Both acts were slated to play rare sets at this year’s Coachella Festival, and both, in their mystery, did at least one thing to upset hungry fanbases — a last-minute ankle injury prompted Ocean to ditch an elaborate stage setup and croon odd versions of old hits from a stool; Paul, though largely true to the hype, declined to offer a livestream — albeit, when the debris settled in the following weeks, both were all-but vindicated by audiences who had little choice but to grant them the benefit of the doubt.

“For old-world acts like Morrissey or Ariel Pink, on the other hand, their exegeses have already come from their own mouths: when a would-be interpreter is met with a blaring megaphone, any impulse for engagement beyond the music is lost in the uproar.”

“It was fitting, proper, and perhaps the only time possible one could form a mosh pit to a Frank Ocean track, so my friends and I did just that,” one blogger wrote of a dubious, and oft-debated, moment from Ocean’s set. “The rest of the audience seemed to be just frustrated and annoyed by this. This was the defining moment of the night to me. An abrupt, harsh sound that juxtaposed the sweet and serene sounds the audience expected to hear. But that’s where they are in the wrong, expecting the same old things from Frank.” For a Frank Ocean or a Jai Paul, it’s in equal part normal and necessary for consumers to take on similar interpretive burdens, because no other authority will ever be present to do it otherwise. For old-world acts like Morrissey or Ariel Pink, on the other hand, their exegeses have already come from their own mouths: when a would-be interpreter is met with a blaring megaphone, any impulse for engagement beyond the music is lost in the uproar.

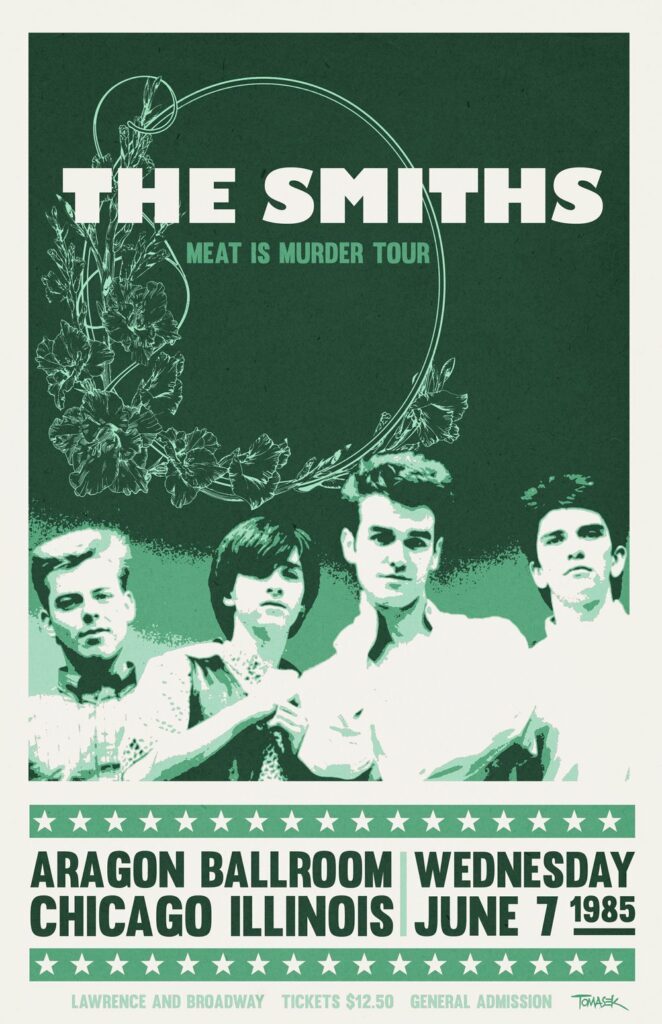

The first title I read from Bloomsbury’s 33 ⅓ series, an ongoing collection of brief books centered around groundbreaking albums, was a canonically-hated coming-of-age fiction set in the suicidally-horny detritus of The Smiths’ Meat is Murder. (“For me this book has only the most superficial connection to The Smiths,” one of several dissatisfied Amazon reviewers wrote, “namely in the form of a few cheap references to the bleak cultural landscape of 1980s Reagan America and a bit of teen angst on the part of the narrator, who spends much of the book pining away for a series of girlfriends while people he knows commit suicide in scenes that feel vaguely reminiscent of Heathers (except with none of that movie’s redeeming humor).”) What made it appealing to me then, beyond its sum of vapid teen angst or Reagan Americana, was its characterization of the group as a voice of self-aware desperation — a far cry from the glitzy corporate rock ethos that had long grown to define bands of its era. Morrissey, in Joe Pernice’s prose, was less of a talking mouth who demanded sympathy, and more of a listening ear who had an infectious way of commanding it. “It was like Morrissey was given the key to a city of morbid, romantic angst,” the book’s smitten teen-aged narrator writes at one point. “He tiptoed over a suspension bridge of glass blown by Marr and Co. It was pop music and ultra-melodic, with lyrics that penetrated my quietest fears with a diamond-tipped bummer.”

“Teenage angst is normal and cool when it’s coming from a teen, but quickly becomes abnormal and uncool when it’s coming from a graying man who opposes Muslim immigration.”

Perhaps the only place where Morrissey’s hopeless-romantic schtick remains permanently applicable is dawdling teenage soul-searching: a confusingly generative stretch, rife with contradictions, where the same adolescent who idolizes outward revolutionaries may also find themselves binge-watching “BEN SHAPIRO EXPOSES CRINGE FEMINISTS” compilations on YouTube at Thanksgiving. Contradiction, though often cringeworthy, is somewhat welcome in teenagers, because they are both known and expected to be morbidly confused. At his height, a large part of what made Morrissey marketable was the fact that he was the ultimate teenager: he pulled his innermost feelings in, and every time a concerned world asked what lay beneath the surface, he pushed it farther away. In retrospect, this exact affirming quality is what, in 2023, makes him irreversibly corny. His innermost feelings, though still ostensibly as potent as they were before, remain locked within a fossilized shell. His interactions with the public, though still limited, are now limited by means of the aforementioned “Messages from Morrissey” tab — a premise as mysterious as it is, in a way, self-aggrandizing. Teenage angst is normal and cool when it’s coming from a teen, but quickly becomes abnormal and uncool when it’s coming from a graying man who opposes Muslim immigration.

The latest “Message” posted to Morrissey’s website, as of the writing of this piece, is dated May 7, 2023, and features a computer-generated image of a crying seal pup stationed beneath the title “Don’t Forget Me.” “For six to eight weeks each spring, the ice floes of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the eastern coast of Newfoundland and Labrador turn bloody, as some 300,000 harp seal pups, virtually all between 2 and 12 weeks old, are beaten to death–their skulls crushed with a heavy club called a hakapik–or shot,” it reads. The grim tidbit is abruptly interrupted by a photograph of a pair of parents and kids, all donning heavy sheepskin winter-wear. “Canada’s absolutely adorable first family. Aren’t they just beautiful?” Much of Morrissey’s artistic approach, both then and now, harps on a similar formula. Entice with a lofty, existential question — “How soon is now?” “Why are we killing the animals?” “Are any of us worthy of love?” — and leave it hanging in the balance en route to happenstance, more quotidian musings: a list that features, but is not limited to, the contents of young girls’ diaries, over-busy hairdressers, and ignorant self-pity for the moments when all of these things fall away.

In the closing verse of “I’ve Changed My Plea to Guilty,” a near-caricaturish single from Morrissey’s 1988 LP Viva Hate, he sings, as he always has, about the oh-so-cold world that has abandoned him. “Something I have learned,” he bellows, “if there is one thing in life I’ve observed / it’s that everybody’s got somebody / Oh no, not me / So I’ve changed my plea to guilty / And reason and freedom is a waste / It’s a lot like life.” In philosophy (a course I am only referencing because I nearly failed it this past semester), the common “Slippery Slope” argumentative fallacy sees interlocutors jump to make exaggerated claims about sequential events with little-to-no logical basis. It’s a favorite fixture of conservative pundits — let them legalize abortions and they’ll start killing you when you’re old just because you’re an inconvenience! — but also, in a larger sense, the canonical language of the desperate. When someone realizes that they aren’t being listened to by a party they once viewed as subordinate, the most promising last-ditch avenue for elusive clout is to threaten. The problem, for the exiled dictators of centuries past, the conservative pundits of days present, and now Morrissey’s old-world alt-pop vanguard, is that threats are only threatening when the people making them have the power to do anything.