LAWRENCE MATTHEWS LIVES AGAIN

Long subsumed, a dead man resurfaces from the grave with new stories—and a new purpose.

SAMUEL HYLAND

When Lawrence Matthews was a 20 year-old upstart, he played his first-ever set at a packed-out indie fashion show, straddled by snapback-clad scenesters who sat, in talkative rows, on either side of his lanky frame. It was a strange arrangement, and by the early 2010s, the Memphis underground was quite a strange arrangement, too. Bubbling at the surface were familiar trap acts, often toting an ossified, Three-Six-Mafia informed ethos—Yo Gotti, Young Dolph, Juicy J. Hugging the bottom of that iceberg, then, meant playing into this history while also subverting it; though trap-adjacency got you in the door, spiking it with something different made you a mainstay. And that night, Matthews, who then performed under the moniker Don Lifted, indeed did something different: so different, in fact, that half the audience immediately walked out. “These motherfuckers walked right through me,” he sneered in a video call, this past March. “Stepped over the cords, stepped through us. I remember being so mad—even if you don’t like it, fine, rock out. But for swathes of people, twenty to twenty-five of them, to get up and start walking through you, not even saying excuse me… That hurt.”

“I can’t just stop. I have to take control. I need to learn. I’m not going to let somebody end me.’”

If you’re wondering what he could have done so blatantly differently, here’s the answer: he was fucked over. The show was something of a ragtag bag-chase, patched together by cash-hungry 20-somethings who saw a scene in the undergraduate underground, and milked it. This was 2011, which meant that being an unsigned rapper, especially in western Tennessee, didn’t earn you the label “upcoming”—it earned you the label “loser,” and prompted people to throw your mixtapes in the trash right in front of your face. (Another relic of the early 2010s: independent distribution was more of a street-corner thing than a SoundCloud one.) Matthews had made his fair share of mixtapes—and seen a fair amount of them trashed—by then, but never performed any of his material in public. So, when the showrunners reached out, it seemed like the makings of a breakthrough, or at least the loose beginnings of one: if he could play a decent set, win a few fans within his age group, maybe pass out a fair amount of CDs, then perhaps, just perhaps, he could kick-start a slow-grind conveyor belt from collegiate fame to cultural acclaim. J. Cole had done it; Vince Staples had done it. Why couldn’t he?

Well, to start, the promoters didn’t have microphones. They also didn’t offer a soundcheck, which means, to any experienced performing artist, that things are irrevocably fucked. Equipped with a shitty karaoke mic bussed down, hastily, from his father’s house, Matthews slogged through the midway point of his first song—a small miracle, until he realized the mic wasn’t even on. And the people, snapback-clad scenesters and schoolmates alike, had long decided that enough was enough. Him, too. “We went to IHOP, and I was just like, ‘Yeah, I quit,’” he said. “It felt like losing a fight in front of the cafeteria at school. When you get whooped in front of your whole school, you don’t want to fight anymore.”

This would be a very short story if the decision lasted for more than twelve hours. “I remember waking up angry, but more like, ‘Somebody did this to me,’” he continued, squinting. “I can’t just stop. I have to take control. I need to learn. I’m not going to let somebody end me.’”

“I’m better than I ever was. I’m immortal.”

On paper, this rhetoric seems fitting for uplifting movie montages—the character says I’m not going to let somebody end me, then the Bon Jovi power-chords start playing, then, forty seconds of fuck-yeah footage later, everything’s better, the good guy gets the record deal, and the evil industry people are all fired. The truth, and one constantly distorted by digital funhouse mirrors, is that Reality is maddeningly different: it limps along lethargically, throws mounds of shit at you when you strive for splendor, fucks you out of feeling like fighting back. In the years that followed that night in 2011, Matthews heeded his own advice—to learn, to take control, to not let anyone end him—into slow-grind notoriety, stocking city-wide acclaim on the merit of multi-disciplinary busybodying. As Don Lifted, he fell comfortably underneath the all-encompassing “alt” designation, an amorphous hip-hop subgenre that, in some contexts, means “not too Black for the white people.” He’d been known, across Memphis’s sequestered indiesphere, for far more than just rap—he shot documentaries, exhibited in galleries, did film photography, worked with nonprofits. And, perhaps most importantly, he had a deal. In 2021, he released his first label-backed record with Fat Possum, the Mississippi imprint known for eclectic signees like Armand Hammer and X. Then he fired his entire team. Then he stopped performing. Then Don Lifted died. “I just want people to love me for being Lawrence,” he said, over Zoom. “Whatever Lawrence is.”

🔆🔆🔆

This summer, Matthews will release Between Mortal Reach & Posthumous Grip, a weighty record that addresses this question—whatever Lawrence is—with debris from Don Lifted’s demise. It’s survivalist to sift through someone else’s detritus: difficult as it may be, it’s proof that you’ve lived, that whatever killed that corpse didn’t kill you. But when you yourself were once the debris, the dung people dropped and left for dead, it’s somewhat different—now, a simple cleanup is a matter of mopping your own bloody guts, tending to them the way its former custodians neglected to. And it’s far more difficult than dying. When Matthews made the decision to do away with Don Lifted, it was largely because he’d had the rug yanked from beneath him. 325i, his first and final record with Fat Possum, was critically acclaimed, but didn’t necessarily do gangbuster business. After the label declined to extend his contract, his management followed suit; not long later, he got a call from his booking agent: “Hey! We want to take you off the website.” Friends faded, loved ones fell out of touch, and for the first time since having lofty industry promises to anticipate—a U.S. tour, another album, a fat paycheck—he had nothing.

Don Lifted, as a character, was someone who purported to not only have something, but a lot. Matthews sits at the end of a two-pronged Afro-Southern lineage, one old enough to remember both the grim gospels of the delta blues, and the glitzy ones proffered by futurists like Outkast. When he set out to make music videos under his old pseudonym, he sought after fantastical, otherworldly imagery—not because he didn’t have a reality worth documenting, but because he thought it would be of little value to his audience. (“My real life, I felt, wasn’t worth showing,” he said, in a recent podcast appearance. “I didn’t think nobody would care.”) And, as he wooed his watchers with put-together productions, the very fabric of his pneuma was ripping apart. Don Lifted wasn’t Lawrence Matthews, after all: he was a product of his creator, the property of his label, and beholden to whatever brought in money—even if the same thing that squeezed in this money sucked out his life. “It was like, I either don’t sign this, and keep working on these little demos, and don’t get no money, and don’t get a shot in the music industry,” he said, of his first contract, “or I do sign this paperwork, and sacrifice myself to move forward. I chose (the latter), and I was in conflict with it.” Midway through the pandemic, as Don Lifted’s future grew fey, Matthews began suffering from a number of things, none of which his camp seemed to take seriously: severe stomach ulcers, asthma-borne COVID anxieties, people literally—not figuratively—out to kill him. In the music video for “Lost in Orion,” one of the final singles he ever put out under his deadname, there’s a shot where his bare feet dangle from the top of the video-frame, steadily rising before a semi-circle of ogling, wide-eyed worshippers. It invokes, very intentionally, two distinctly polar opposites: the public lynching of an enslaved person, and the heavenly ascent of a Christ-figure. Regardless of the one you choose to go with, two things are true: (1) the man those feet once belonged to is dead, and (2) the people watching them rise are largely responsible.

“People are looking and going, ‘Man, we cannot break an artist in town. We haven’t done this in decades. Something has to change, and that means we have to get rid of a lot of the old, to make way for the new.’”

Don Lifted died a gradual death, one that mostly happened in private. But if history were to reflect a single moment where he was publicly murdered—by the man who, years ago, vowed that he wasn’t going to “let somebody (else) end me”—it would place us at Memphis’s Overton Park Shell, in the Fall of 2022. He’d been booked to perform there long before he lost everything; rather than opt out, he sought to stage a dramatic re-introduction, something of a hard-launch for not only his dead past, but his looming afterlife. He told the audience he wanted to share new music, went backstage, changed his clothes, and returned: this time, with both a new outfit and a new name. “For the first time in a long, long time—maybe ever—I felt completely free as an artist,” he said. “There was never a moment where I was concerned about whether people would understand what I was doing. I told them to come down to the stage. The applause, the ambience, the things I was hearing as I was doing what I was doing… All I could say was, ‘See? This is what I was talking about.’”

“I’m better than I ever was,” he continued. “I’m immortal.”

Four years ago, Matthews directed and filmed The Hub, a forty-five minute movie-documentary that followed several Memphis men through the city’s bleak, often abusive, entry-level job market. In its wordless opening minutes, we’re silent voyeurs to a consternated-looking man in a shredded baseball cap; he sips on ninety-nine cent drinks from corner stores, takes drowsy, quotidian bus rides, slinks through overgrown shrubbery, glares at oncoming traffic. When the prologue ends, and the color palette shifts to black-and-white—a recurring relic of Matthews’ early films—clips from two separate real-life interviews recur in ruthless succession, each revolving around its subject’s labor-borne struggles. “I was supposed to clean the bathroom one day, and there were human feces on the bathroom floor,” one of the men, a bespectacled twenty-something, recounts, early on. “And I went to my manager and said, ‘I’m not doing this. This isn’t my job description.’ I was put on probation. They called me back in another week or two—without pay—and pretty much told me they were letting me go.” In its remainder, The Hub intersperses similar on-the-ground testimonies (monochrome) with a fictionalized narrative (color), in which a young father braves rocky terrain to reinvent himself—less for his own good, and more for the appeasement of job interviewers. By credit-roll, when the hours-long bus rides, difficult conversations, barber-shop line-ups, and passenger-seat insults are all finished, we aren’t told whether he ever finds work. Even in its colorful moments, the movie is blunt in its austerity, its abrasive anti-climax. You leave with the sense that you’ve been hung out to dry. “It makes you feel depressed,” one of the real-life interviewees says, regarding Memphis’s infrastructure, at one point. “It makes you not want to show people where you come from.”

“I don’t give a fuck about who became a billionaire this year. But everybody thinks they’re going to do that. And they’re not.”

In its centuries of being ogled at by distant city-dwellers, the South has borne its fair share of myopic stigma—stigma that, to this day, casts it as something bleak and barren, a land of beauties that must be “extracted” before they can be understood. Matthews, a lifelong Memphian, has devoted his career to proffering a more nuanced outlook. But troublingly enough, as he’s spent the past decade learning first-hand, the most sellable stories tend to be the most familiar ones. Much like the splintered underground he emerged from, Southern songwriting skews to reward two extremes: trap-informed braggadocio, the sort that splurges on sex raps and stick-ups, or escapist “alt” dispatches, less concerned with the real than the out-of-reach. In Matthews’s Memphis, the most profitable people are both real and out-of-reach at the same time. That’s because in Matthews’s Memphis, the most profitable people are dead. “In Memphis, there’s been a lot of ‘dead worship,’ if that makes sense,” he said in a Zoom call, this past April. “A lot of the dead musicians get all of the market share. With most of the trap musicians, as soon as they get on, they get to Atlanta. The belief is that you can’t have things here, so they don’t actually take up local market share. But the dead people do. Elvis, and Otis Redding, and everybody from Stax.

“We fuck with that stuff, of course,” he continued. “But I think because of that, it’s created an environment where it’s just hard to get new, original musical things off. People are looking and going, ‘Man, we cannot break an artist in town. We haven’t done this in decades. Something has to change, and that means we have to get rid of a lot of the old, to make way for the new.’”

Here’s where Matthews’s predicament gets complicated: as of right now, he’s both the old and the new, the real and the out-of-reach. No, he isn’t dead. But he also kind of is. There’s a vast population of people, both within city lines and across the digisphere, who look at Lawrence Matthews and see Don Lifted—not only an obsolete character, but in being so, a denizen of the past that must be gotten rid of for the future. Fewer are the followers who see him as he sees himself: a new artist, making new music for new meanings, new contexts, new purposes, new people. Most have treated his transition like the rest of America treats the South: hesitant, if not simply unwilling, to release a familiar narrative for a more accurate one. And in the words of The Hub’s troubled young men, it’s depressing. It makes you not want to show people where you come from.

But Matthews still does. It’s why Between Mortal Reach & Posthumous Grip, unlike anything he made under his deadname, is dedicated, specifically, to people who exist in real life: the ones outside, largely offline, looking for work, getting shape-ups, raising children, reinventing themselves. Because those stories are real. And it’s a reality worth dying for—just ask Don Lifted. “Certain publications will literally post, ‘Such-and-Such Just Reached A Billion Dollars,’” he said, last March. “Why does that matter to us? We don’t have free healthcare, no student loans forgiven, none of this shit. People are living horribly in this country. I don’t give a fuck about who became a billionaire this year. But everybody thinks they’re going to do that. And they’re not.

“So for me, it’s just this: let those guys do that, and let everybody go join them, and be in the metaverse, and put headsets on,” he continued. “I’d rather be in the world with people who live regular lives, try to pay their bills, and do normal people shit. Because there’s way more of those people than there will ever be billionaires and millionaires. These are the people I see in the streets. I know these people. I’m friends with these people. I am these people.”

“You always want to try to plan, like Oh, I move like this, or I got it on me like this, or whatever. But when it be there—it be there. And you don’t know when it’s gonna be there.”

For a while, he was close to not even being a person. Matthews came across the phrase “Between Mortal Reach and Posthumous Grip” in a newspaper, but in his own context, its meaning is nuanced, even if the nuance is somewhat grim. He’s fortunate—and unfortunate—enough to have spent much of his life surfing middle-grounds: between divorced parents, between wealth and poverty, between being acclaimed and being forgotten. By 2020, he felt he was between life and death. It helps to get the obvious, more communal grim reapers out of the way; COVID-19, wildfires, trigger-happy cops at tragic traffic stops. Closer to home, both personally and locationally, were other things—the aforementioned enemies plotting to kill him, the untimely deaths of local legends, the slayings of scenesters he came up with—and all, eerily, while he was recording. MO3 was shot dead on the interstate. Young Dolph was shot dead at a bakery. PnB Rock was shot dead at a Waffle House. “You always want to try to plan, like Oh, I move like this, or I got it on me like this, or whatever,” Matthews said, in April. “But when it be there—it be there. And you don’t know when it’s gonna be there.” Though Matthews doesn’t claim any religion, he’s a deeply spiritual person, and much of his new album’s battles are fought on spiritual turf. He’s making threats, but not the stick-up sorts typical of trap records, nor the escapist ones he once leaned on—most times, he’s gesturing towards psychic innards, the pneuma that lies beneath every opp, every hater, every assassin. You get the sense that he’s old enough to hit where it hurts. You also get the sense that he’s been hit there before.

Since his departure from Fat Possum, Matthews has released music exclusively under a self-created imprint called “Golden Boi.” Its namesake is a 2021 Don Lifted single; much like the zombified character that made it, that track sounds sickly: over a deathbed of reverb and drowsy, unmoving guitar phrasings, a monotone Matthews pleads for patience, a sliver of the virtue he has good reason to abandon. “Don’t slide on me, don’t lie to me, don’t glide on me,” he sings, maybe to everyone, maybe to no one. “Just wait.” Over Zoom, he mentioned that the refrain was a “prophetic kind of thing.” Up to then, he’d spent years referencing a move he was going to make, a “new” plane he was bound, sooner than later, to mount. 2021’s Don Lifted had already done a lot of upward movement. That character had critical cred, local legend, a profitable foot in the art world; Just wait, he’d said, and if you were watching, you might have wondered: wait for what else? Three years later, it’s eerie, maybe prophetic, that the “wait” wouldn’t be for a future—it would be for the gutting of one. But there’s a sinister endurance to it all, in that there’s a different wait, now: the wait to see whether artistic suicide, or its years-long rebuilding process, was ever worth it. “When we made that song, it was very much me celebrating that I was right,” he said. Don Lifted wasn’t right. But Lawrence Matthews just might be.

🔆🔆🔆

“You keep building a life on top of a life on top of a life. And there’s remnants of your past lives everywhere you go, and you can’t escape them.”

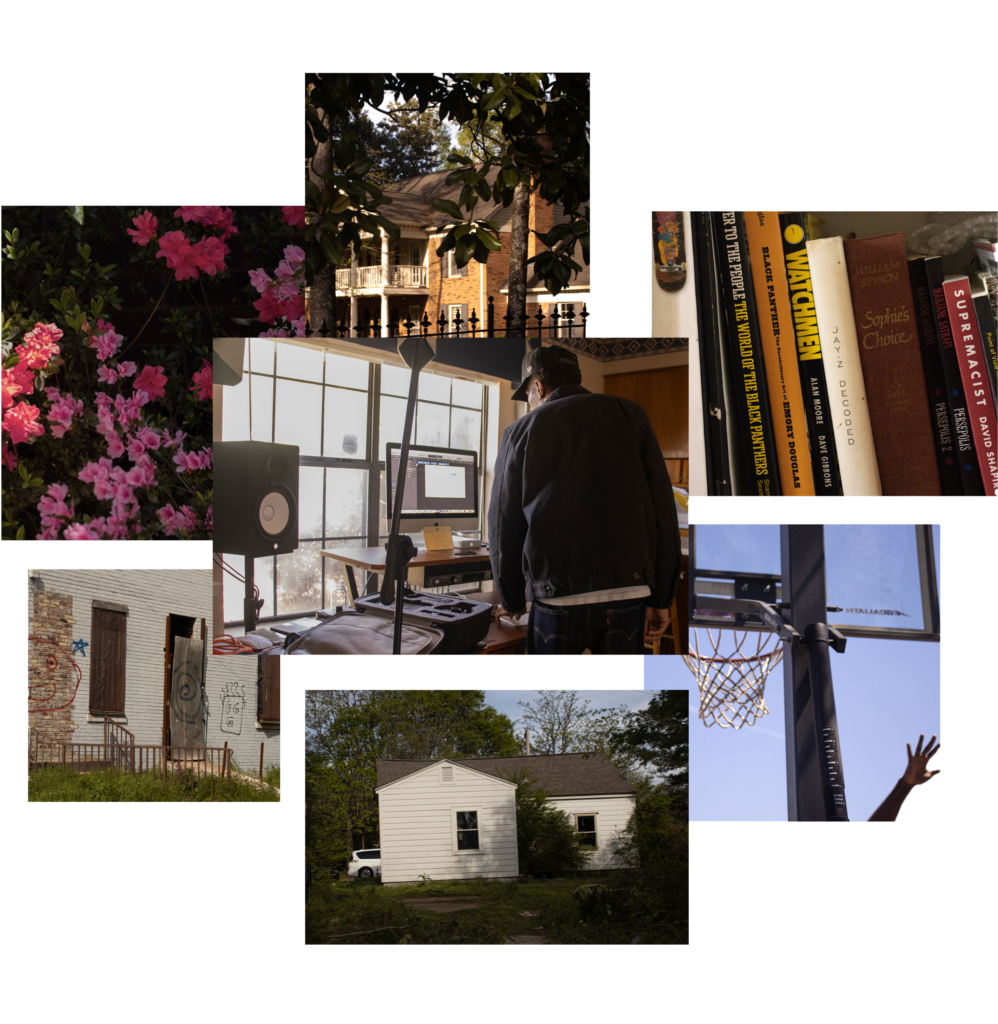

The road to Lawrence Matthews’ house is twisty and bare, an S-shaped expanse that, in the right amount of sunlight, seems almost too spotless, too suburban. It was sunny on the first Saturday of April. The oppressive, cloudless kind. A solar eclipse was slated to occur within 48 hours, and our doomed despot had seen the schedule; it glared down upon its sweaty subjects, daring them to come out, daring them to suffer. The sidewalk leading to Matthews’ home was lined with open garage doors, shady neighbors peering, mid-conversation, at the black SUV skulking slowly down the street. When the SUV reached the address it had been given by a publicist, it was about half-past noon. Matthews stood in the gray of his garage, signaling. He was wearing mostly black: a black trucker hat, a jet-black bomber jacket, dark-wash jeans, Timbs. It was hot outside, and it was strange to see him stand there, unsweating, unwet. The air in his house was even thicker than the air outdoors. It felt like the walls were closing in.

For Matthews, they very much were. Since his family bought it in the 1980s, he’s grown up to watch the house change hands—from his father, to his mother, and now, as of the past decade or so, to him. It’s an unsuspecting single-story brick cottage, three bedrooms, two bathrooms. He shares it with a partner, though in practice, it’s something of a makeshift headquarters, where friends and family fight summer heat with long, gusty evenings of games and gab. In the backyard, a sizable expanse equipped with a ragtag concrete basketball court, about a dozen relatives and homies barbecued; while an impromptu slam-dunk contest raged on in the middle, cousins and siblings lined the perimeter, blasting soul music. Matthews surveyed the space like an elder, or maybe a content camp counselor. Occasionally, he’d throw a stray basketball back court-ward, or dap up a new arrival. In two days, he would officially put the house on the market. He didn’t know where he was going. But he knew he had to leave. “It’s very dangerous to be existing in the same place that I was when I was in kindergarten. It starts to get real Synecdoche, New York,” he said, referencing the 2008 Charlie Kaufman psych-drama. “You keep building a life on top of a life on top of a life. And there’s remnants of your past lives everywhere you go, and you can’t escape them.”

“I want them to hear that, and then see me where I am, and go, Damn! He was there, and now he’s here? So whatever my valley of the shadow of death is: I can get to there, too.”

Between Mortal Reach & Posthumous Grip was borne of similar crossroads. When Matthews killed off Don Lifted, it wasn’t as if the flatline was immediate—there was spasming and leg-kicking, like a cockroach drenched in Raid; except, Don was real and rabid, a ghost that haunted the present, clutching it for dear life. There was a man in the process of being murdered, a decade’s worth of work whispering out like blood: of course Mr. Lifted wouldn’t go down without a fight. The alter-ego was something of a buffer from reality, the very reality he now creates for; he was a capital-A artist, whose forays into the haute and highbrow excluded, maybe even exempted, him from the bleak determinism of Memphis’s day-to-day ordinaire. It’s a privilege, especially where Matthews hails from, to be able to work from a studio instead of a factory, to put your hands to files instead of feces. And now, at the lowest point of his life, here was this reality staring back at him: if he didn’t make the absolute best music he’d ever made, he wouldn’t get to speak for the people under Memphis’s boot—he would simply be the people under Memphis’s boot. And he would die there. “It’s valley of the shadow of death type shit,” he said, perched on the arm of a couch. He seemed to get an idea, and he raised his voice like a preacher would, strained syllables sent echoing off the revolutionary texts lining the walls. “I don’t necessarily want to motivate people to feel the way I felt in an album—at all. I want them to hear that, and then see me where I am, and go, Damn! He was there, and now he’s here? So whatever my valley of the shadow of death is: I can get to there, too.”

It took a while for Matthews to get where he is, and the way he sees it, it’ll take even longer for him to get where he wants to be. He thinks largely in terms of narrative arc: projects denoting stepping stones, eras denoting roving plot-lines. He’s already several albums ahead. After a half hour or so outside, he slinked through a covert back door, hand-clasping relatives between stern stay commands to his curious dog, an American dingo named Roofus Barktholomew. Back indoors, he sidled into a makeshift home studio, the way a gray-haired fighter pilot might strut into a cockpit. The studio sat in a dining room that bordered a sunlit kitchen; through the window, the jolly festivities of the backyard raged on, a stark contrast to the spiritual battleground a pane of glass away. Underneath a mammoth computer monitor, there laid a loose assortment of ephemera, maybe inspiration—20th-Century books of Black art and folktales, complex hand-scrawled checklists, nicknacks from past trips. For much of Between Mortal Reach, Matthews consulted the people, largely art-adjacent friends of his younger brother, on the other side of the glass. “I would set the mic up and put the chairs around it,” he’d said in the backyard, “and be like, ‘Alright, here’s the microphone, and here’s the headphones.’ Or, I would do it one-by-one: like, ‘Boris, you go for it, go through your ad-libs,’ then ‘Alright, Kyle, you come say whatever you feel.’” Midway through the recording process, he’d realized that he was at a pivotal, all-important juncture—not only for his career as an artist, but for his life—and asked a friend to take photos. In the ones he pulled up on the monitor, reference printouts lined the walls, like evidence thumb-tacked to interrogation-room cork boards. There was a living mess, of sprawled equipment and loose paper, centered by another living mess, hunched over a mic in hopes of cleaning himself up. It looked like a fight to the death.

“I want this album to sound like somebody losing their mind and putting it back together again.”

He closed out of the pictures and opened another folder, this one dedicated to Between Mortal Reach’s scheduled follow-up. Maybe even more than its predecessor, the record zeroes in on Matthews’ strange, lifelong in-between-ness. It’s somewhat removed from the deathly weight of his forthcoming project, but not necessarily exempt from death, nor its looming, all-seeing specter. “It’s tricky—it can drive you fucking crazy,” he said, of the half-and-half terrain Black artists are often tasked with fielding. “I’ve definitely had to navigate that. Most of the time, Black people, or Black entertainers, go one way or another. I told Nigel [Mack]: I want this album to sound like somebody losing their mind and putting it back together again.” There’s a damning commercial middle-ground, of course, between being too Black for white audiences and vice versa; but also a grimier, existential one familiar to Matthews, long undergirding his tightrope-act between sects, contexts, worlds. One late night, he was leaving the home of a sister, when he found his car tightly sandwiched between two other manned vehicles. The rest of the street was empty. “As soon as I get to my car, this door opens up,” he recalled, using three items on the desk—a sticker, a computer mouse, a bag of wires—as makeshift stand-ins for the automobiles. “A dude gets out of it, and he has a shiesty mask on.” The door opened, and the masked man approached. Matthews reached for his gun. “I’m sitting there like, Here it goes. Here’s this moment you’ve been paranoid about.” Nothing happened: the man kept walking. But Matthews still thinks about it often. “That’s the thing—what if I was too itchy? Too paranoid? Too in fear? Everybody’s dead. That’s what happens.”

He parsed through the second album’s dedicated folder, and settled on a dense-looking Logic file with fourteen stems. The track was squinty-eyed and low-down dirty, a tense ballad that rode slap-bass and big-screen samples into something sinister, sinuous, serpentine. In its second and final verse, a tour-de-force interrogation of Bentley-owning pastors (“Bet God really loves you”) and cash-hungry clergy (“Where them tithes at, don’t you know we need a new roof?”), he barrelled towards a steadfast conclusion, albeit one that ended with a question mark, not a period: “Push me to the edge, who the fuck I’m supposed to pray to?” You could picture him stern-faced in the studio, gnashing his teeth, snarling. He had been at the edge when he recorded Between Mortal Reach, and in more ways than one, he still sort of is. The last time he was here, he had a different name, and he threw himself off the cliff. He’s back now. And ultimately, there’s no one to pray to, no one in charge of his fate—no gallery investors, no major label advances, no America—but himself. These are tough odds. They’re also the best odds possible.

🔆🔆🔆

A few hours later, the sun was setting, and Matthews was cruising down the blood-red streets of Memphis in a worn BMW 320i, three passengers—a journalist; a photographer; his partner, the contemporary visual artist Ahmad George—in tow. There’s a splintered quality to the city he grew up in, the maddening sort of spell that puts shantyhouses and strip clubs mere corners away from commerce, corporations, castles. Hickory Hill, one of the first neighborhoods he steered through, was lined with stripped-down stretches of empty concrete, hollow ghosts of the bustling cultural cache they once commandeered. A little over a decade ago, a devastating tornado ravaged the area, damning heaps of infrastructure—and heaps of people—to untimely, dirt-trodden demises. As white homeowners fled, people of color trickled in, and with them, a newly-recognized town nickname: Hickory “Hood.” Through Matthews’ back window, the roadway was all mud and cement, foreclosed businesses and barren lots punctuated by large, garish church buildings. “The worse things get, the more of those pop up,” Ahmad said, gazing out at one. Matthews tossed a knowing wrist-flick towards New Direction, another large Christian assembly to his right. At the foot of its parking lot, there was an unhoused man sleeping on the sidewalk, the curb his pillow.

“And that was weird. That wasn’t normal. Because they had seen themselves. They’d seen what shit looked like for real to them. Not the fantasy stuff.”

Perhaps the most in-between thing about Matthews, or at least the source of his lifelong in-between-ness, is the fact that he’s from a chronically in-between place. Case in point: within ten minutes, lush greenery was gradually replacing mud, and we were barrelling towards Graceland, the lavish Elvis Presley estate that racks up over ten million tourist dollars per year. This is what Matthews means, when he says Memphis’s most profitable are its dead—huddled around the estate’s entrance were human embodiments of its market share, mostly older rock-aficionados who’d dragged their families to pay respects to their long-gone god. There was a massive hotel across the street, and, just like Hickory Hill, a large expanse of pavement. Or, maybe, this particular expanse of pavement wasn’t exactly like Hickory Hill’s at all. It had a tollbooth, and it had living beings, too. A few hundred of them, each with more than a few thousand dollars in checkings.

These sorts of living beings—the necromantic ones, who shirk Memphis’s culture for its corpses—aren’t the types Matthews is concerned with, anymore. Where Don Lifted took priority in profit, the quickest means of currying cash (and clout) from commercial entities, his successor is a project in people, the realest means of telling rawer, richer, stories. Between Mortal Reach isn’t out yet, and because “new name” technically equals “new artist,” streaming numbers aren’t necessarily in the millions. Which would have mattered, maybe even a lot, to Mr. Lifted. Not Matthews. His family is split between his mother’s side, largely art-adjacent individuals in various creative spheres, and his father’s side, mostly workers with physical, labor-intensive jobs. The latter was somewhat dismissive of the Don Lifted stuff. But both sides reacted strongly to the two new singles, “Green Grove” and “Limelight Honey,” he’s put out under his government name, thus far. Each of those music videos eschews fantastical terrain for recognizable, down-home truths: he’s hooping in his own backyard, taking film cameras to his surrounding streets, fraternizing with people he knows in real life. “I was in New York (when “Limelight Honey” came out), and when I came back, my grandma had watched the video, and was talking about it, and passing the phone around the table,” he’d said earlier, in the backyard. “And that was weird. That wasn’t normal. Because they had seen themselves. They’d seen what shit looked like for real to them. Not the fantasy stuff. So when I came back, they were like…” He slapped his hands together to mimic a hearty dap-up, the intense kind that generates heat. “I see you, nigga. That shit was hard.”

“Everything that he’s doing, I wanted to do.”

Shortly after he turned off the main road, Matthews slowed near a small one-story home crawling with kittens. The house sat at the corner of a large expanse of grass; the young cats roamed freely, some seated on the tops of cars, others glaring at traffic from beneath pieces of furniture, pawing at themselves. The woman in the yard had seen Matthews, and he knew it. “Of course she did,” Ahmad said, breaking into a guffaw. “Now we gotta stop.”

He pulled the BMW into the driveway and hopped out, crunching through the grass en route to a short metal fence separating the front and back yards. The woman on the other side was bespectacled and sarcastic. She wore a tight ponytail of shiny, silver hair streaked with black; her expression was somewhere between stern, skeptical, and sardonic. “Hey Aunt Shirley,” Matthews and Ahmad called out, in unison.

“I got some folks in town, doing some interviews,” Matthews started. “I just brought ‘em by. I wasn’t even—”

“Interrupting my cats getting fed,” Aunt Shirley retorted, interrupting him the same way he’d interrupted her cats getting fed. “It’s dinner time out here!” He introduced his guests, a pair of 20-somethings. “It must be good to be young,” she said. “Just running around doing nothing.”

When Matthews was a kid, he’d done a lot of running around, and a lot of nothing, too. He spent long hours idling in Aunt Shirley’s house, absorbing her dual affinities for flashy cars—BMWs in particular—and flashier records. Before it was redone, her bedroom featured a mammoth wall of vinyl LPs; it was there, craning his neck, that he first learned of acts like Prince and Jimi Hendrix. His first instrument was a guitar. He wouldn’t have gotten it—and there’s a good chance he wouldn’t be a musician, either—if it weren’t for Aunt Shirley.

“Do you have anything nice to say about Lawrence?”, one of the guests asked, and Matthews sheepishly plugged his ears, promising that he wouldn’t listen. He smiled a childlike smile, an expectant smile, a smile that he seemed to have smiled many times, many years ago.

“He’s a great person, and not just because he’s my nephew—he is truly a great person. It’s amazing that he is so gifted,” she said. “All of my nephews and nieces and greats, they’re all very gifted. This family’s very gifted. It’s just that when we came up, we didn’t have all these opportunities.

“Everything that he’s doing, I wanted to do,” she continued. “When I went to school, and I was doing spoken word, they couldn’t see it. So I said, ‘Okay. Just wait.’ And now, it’s here. So I’m happy. Because when he gets rich, ‘imma be rich, too.”

As the quartet made its way back to the car, Matthews looked back at Aunt Shirley to tell her he’d reach out soon regarding another music video. She’d been in the “Limelight Honey” film, and she had her reservations: “I hope it’s not like that last one,” she demanded. “So embarrassing! All that twerking… I didn’t want my friends to see it! I’m kidding. I told everybody about it.”

The front door cracked, and a voice came from inside the house: “Aunt Laura’s been listening, too!”

“Say whatever you want about fate, and destiny, and all that: it put me in the perfect place to question a lot.”

And the BMW was off, speeding through the day’s final moments of golden-hour sunlight. One of Matthews’ final destinations, before dropping the guests back at his house, was Shady Grove, a filthy-rich locale packed with gated, well-hidden mansions. He’d been there before. A decade or so ago, when he made most of his money scrounging up the art-world ladder, he went on long delivery drives through its secluded streets, carrying his paintings on the roof of his car. You had to live a certain way—and in many ways, you still do—to purchase Matthews’ artwork. (A 40×60 print of his photography goes for $6,000.) The customers of Shady Grove lived that way. And in many ways, they still do. The view through the car window was overwhelmingly green, pristine, picturesque: a far cry from the barren, church-owned concrete sitting a $30 Uber ride away. When those delivery drives were done, and the sun set on those far-away castles peeking out from high-up walls, Matthews had to go home. He always had—Don Lifted was acceptable insofar as he came, entertained audiences richer than he, then went his separate way, the way that meant counting food-stamps while they fine-dined, driving home while they were chauffeured, living by the paycheck while they were living by the pleasure. Solving this problem, of the working class laboring for the upper crust, would mean solving America: a difficult task. But if killing a puppet of this process is anything, it’s a step. “It’s an interesting space to be born in the middle of,” he said, of Memphis. “Say whatever you want about fate, and destiny, and all that: it put me in the perfect place to question a lot.” Himself included.

2 replies on “Lawrence Matthews Lives Again”

This is a very well written interesting article. I couldn’t stop reading it and I know Lawrence! Thank you for sharing your day in the life Lawrence.

Great coverage! Love reading your style and use of imagery. One of my favorite lines: “It wasn’t as if the flatline was immediate—there was spasming and leg-kicking, like a cockroach drenched in Raid.” It creates a magical world out of the real one.

The exploration of life and death, and death and re-birth was excellent. You explored it at every level, and I thought it was a great way to understand Matthews. Love your work Sam.