It Can Be Done, But Only Keith Can Do It.

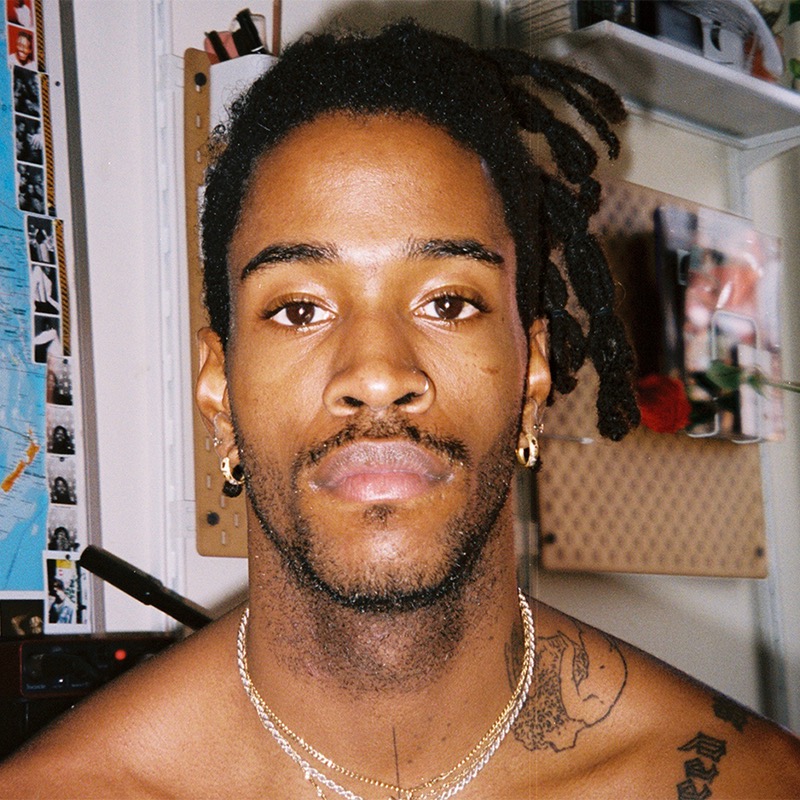

Since Hip Hop’s New York beginnings, roles of rapper and producer have gradually grown apart – but, decades later, there remain artists that continue to don both titles. On paper, KeithCharles epitomizes such early rap scenes: DJing/rhyming combos; Manhattan residency; gritty flows. Off the screen, however, he lives out a portrait of just how much things have changed.

SAMUEL HYLAND

Back in June, KeithCharles did a set for Mixcloud’s ongoing Sidenote series. He titled it ‘Relentlessly Thuggin’.’ “It’s about enduring the hardships, overcoming the pain, and facing things head on,” he said in a brief introduction. “So just keep your motherfuckin’ head up, let’s get it.” The twenty-six minute mix musically embodies Keith’s brief advice: throughout, there are allusions to Des’ree’s 1999 single You Gotta Be (“You gotta be hard, you gotta be tough, you gotta be stronger”), emboldened post-breakup mantras, and overtly masculine ad-libs emblematic of a hustling lifestyle omnipresent in representation. The common thread, however, whether tackled through soul samplage, banging snare, or strained falsetto, is that all a playa can do is play: the only way to get to the light at the end of the tunnel is to walk through it.

Today, Keith takes a brief pause before answering my question about what the hustle has looked like for him. “One thing about niggas . . . us black men – we’re pretty much taught in America that the only way to get through anything is to get some money,” he tells me. Much of what’s under Keith’s belt attests to this. Behind him in his Brooklyn apartment, a baritone Squier Jazzmaster guitar is strewn across a mattress off in a corner, framed artwork surrounds a McCartney-esque violin bass hung up on the wall; it’s all the makings of a wealthy artist-in-residence persona you’d find smeared all over the dreams of starstruck city kids who drool over on-screen depictions of Central Park high-rises. But it’s also the physical manifestation of a lifestyle Keith has been working hard to sustain. When he left Atlanta and Awful Records – the collective that, for a decade, fostered his ascent into hip-hop prominence – in 2015 to come to New York in search of his own creative identity, money was constantly in danger of running out. His Instagram may display collaborations with brands like Converse and Adidas, or photoshoots for high-end modeling firms in the city; but, these things weren’t a matter of choice as much as they were a matter of necessity. “Eventually I kept getting hit up by different brands, or casting agencies,” he says, referring to the aftermaths of various promos he would post to his social media accounts in the past. “They would be like oh, are you available for this shoot– I don’t give a fuck, I need some money. I need to pay my rent.”

Thankfully, coming off of about three years of this struggle, Keith has been able to find some level of artistic freedom. Money still isn’t Bill Gates high – just not at a level where his next paycheck depends on startups hitting him up on IG for press shoots. Now he can hone in on his art, which, at every dimension, is defined by the dynamic of doing it oneself. He produces his own music so he doesn’t have to pay someone else to do it. He told his mom at eight years of age that he needed an MPC, because no one else would make the music he wanted to hear. And as of now, he’s picked up guitar solely for the purpose of not having to ask someone else to play something only he can emulate to his liking. As we chat about this, he leans back into his office chair, arms crossed behind his head as if to search for the right words floating by in mid-air. “I don’t want to not know how to make my own music,” he concludes after a few seconds. “I don’t want to hear a riff and be like fuck, I wish I could play that. Just to hit somebody up like play it but don’t play it like that, or go a little higher, or change up the strum pattern.”

“Well did you want to be the first to do it, or did you just want to do it?”

What puts Keith’s drive to learn in perfect perspective is how quick he is to grab his guitar off the bed when I ask what riffs have been in circulation lately. He’s excited about the first one, Footsteps in the Dark by the Isley Brothers. A split second after the title leaves his lips, the guitar is across his lap: he’s intently strumming away with what – though this is something he picked up just this year – looks to be the comfort of a happily seasoned jazz musician. The adventure in his eyes, in contrast, is of a kid in a candy store.

He stares intently at the fretboard as the song comes to life. For just a few seconds, it sounds like Ernie Isley is in that apartment complex. Pausing between transitions from barre chords to fingerplay, he works the riff towards perfection until it looks as if the Jazzmaster and the man holding it are telepathically communicating; although there are pauses here and there, the music does not stop until it sounds just like a studio cut. When satisfied, Keith casually tosses the guitar back onto the bed as if nothing just happened.

Up to now in our chat it’s become clear that his musical upbringing is in constant conversation with where he is now. “I only listened to what my family was listening to,” he said early on. “My grandmother would be listening to, like, the Clark Sisters, and my mother would be listening to Parliament-Funkadelic.”

Something Keith mentions later is that he only started listening to Northern rap music in his late teens. In high school, he went through a period where he brainwashed himself into a musically elitist archetype: everything that was coming out at that point, whether it be Lil Wayne or Kanye, was automatically disregarded as inferior to the stuff of New York’s hip hop renaissance decades prior. When I muse to him that “Everyone’s an old-head at thirteen,” he agrees.

Yet up to present-day, under the monikers of both KeithCharles and KeithCharles Spacebar, he’s crafted a discography that audibly fuses all of these scenes into one another with striking spontaneity. He raps with a New York grit that draws countless comparisons to early-stages A$AP Rocky; his art direction drives hordes of followers into misguided nineties nostalgia (“He sounds like we’re in the nineties??? I swear I don’t try to make old-school sounding shit”); many of his releases take after the lustful themes of renaissance funk records.

One single that paints a perfect picture of this complex is Heartbreak at our Age, from his 2019 EP i love you, but you already knew that. The two-minute track opens with a sentimental piano groove reminiscent of jazz’s through-line to New York’s nightlife, later evolving into a bass-heavy warble of not letting a broken heart also break one’s pockets. Given the fact that there is little information about the song online except for its music video, online listeners are noticeably quick to formulate conclusive opinions for themselves.

“Use me as a “I love it” button,” one user suggests. (It’s the most thumbed-up comment).

“He lowkey sounds like Rocky,” says another.

This 90s vibey track is straight fire. Kudos to this kid.”

“This video was good. You need to get on TV.”

“Love the vibes and the unique flow this song brings its honestly refreshing. Also its laid back and chill song while also being upbeat. Vibes. Love it. Great song!”

It takes some convincing to get Keith to read his Youtube commenters’ words. “When I first released music in like 2012, 2013, people hated my shit,” he tells me. “My Youtube comments used to be so mean. I was like ‘I’m never reading this shit again.’”

After some nudging, though, his face brightens up with the reflection of a white computer screen. With a few clicks of the mouse, he goes silent for a while. His eyes move up and down, left and right.

I check back in with him. By now, he’s clicked on several videos of his. “This is nice — these people are actually nice!”

But when you get new shit, it’s normally just . . . malfunctioning. Don’t put me in the rocket ship. Don’t put me in the off-white spacesuit.

Keith has one bio for both his Instagram and Twitter accounts: “It can be done but only I can do it.” It’s a mentality he’s carried with him for just about all of his artistic career, from playing organ in his mother’s church as a child to playing solo concerts in major cities across state lines years later. Anyone can make music KeithCharles likes. No one can make music like KeithCharles.

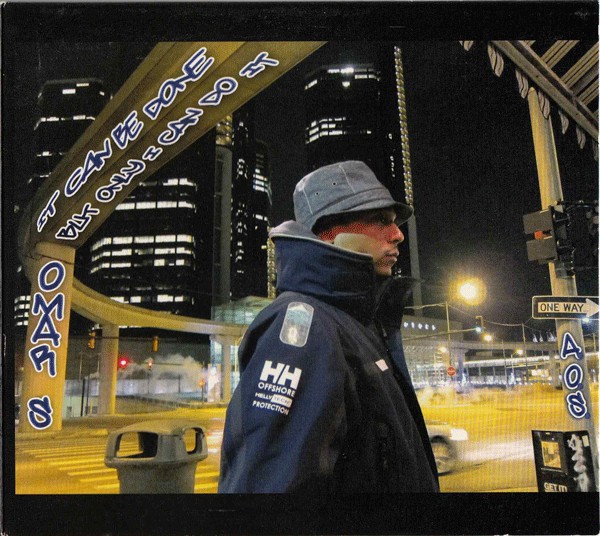

This principle ironically manifests itself when I ask whether his bio-of-choice is inspired by Omar S’ 2017 album of the same name. “It says the same exact thing?,” he asks me. He’s shocked when I show him the album cover on my phone (“Oh, what the fuck?!”). But not to the point where he’d make drastic changes to his social media accounts. Being the first to do something doesn’t matter to Keith: he’s more content with doing things in ways that no other human beings past and present ever could. After all, the album cover mixup is a coincidence – our conclusion is that the government definitely knows something we don’t.

Between me asking about the bio and showing him the album cover, our discussion shifts towards doing for the sake of pioneering versus doing for doing’s sake. I talk about how, from a writing standpoint, when a publication has already written about a particular thing, it becomes very discouraging for one to pursue writing about it themself.

“Well did you want to be the first to do it, or did you just want to do it?,” he asks. “I don’t want to be the first to do anything.”

“Why not?”

“First nigga on Mars? Never happening. I don’t want to do that. I don’t give a fuck about being the first nigga on anything. But when you get new shit, it’s normally just . . . malfunctioning. Don’t put me in the rocket ship. Don’t put me in the off-white spacesuit.”

For now, there will be no rocket ships or off-white spacesuits for Keith to worry about. These days he’s focused on rolling out his upcoming project (yet to be named), for which he already has a supporting single pending release. It will be the first full-length release of his since 2015’s We’re All a Little Triflin,’ the only album he put out with Awful Records.

And a lot’s changed between then and today.

The Keith Charles of five years ago slept on couches, lived paycheck-to-paycheck, and navigated bridging a chasmal artistic gap between Atlanta and New York City (he has ATL in the ‘better hip-hop city’ debate) on empty pockets.

But the Keith Charles of 2020 has enough financial – and artistic – freedom to fully delve into the very thing he came to New York to find: individuality. He isn’t the first to rock an A$AP Rocky-esque flow; he isn’t the first to quote the title of an Omar S. album; he isn’t the first to call Manhattan a creative home. But he is the first to rock an A$AP Rocky-esque flow the Keith Charles way. He is the first to quote the title of an Omar S. album the Keith Charles way. He is the first to occupy Manhattan the Keith Charles way.

The interview closes with me wishing him luck on learning guitar with a Jazzmaster. There are several riffs he’s adamant about perfecting, from the Isley Brothers track he briefly covered early on, to Modjo’s 2001 club hit Lady (Hear Me Tonight), which he went as far as to send me a link to mid-conversation.

These are difficult songs to master. Nile Rodgers, the mastermind behind the former, is listed top-five in just about every extensive funk-guitarist ranking online. Footsteps in the Dark is one of the Isley Brothers’ most sought after tablature diagrams on Ultimate Guitar.

But as we wrap up our interview, the rule still stands.

It can be done – but only Keith can do it.