CASE STUDY: IN SEARCH OF SUBURBAN LAWNS

Suburban Lawns predicted the future. Then, they disappeared.

SAMUEL HYLAND

One of the strangest places where evidence can be found that Suburban Lawns, the mysterious 1980s Long Beach existential rock band that disappeared just as quickly as they arrived, predicted the future, is a brief-albeit-iconic interlude in the theme song of another notorious cultural prophet: the Simpsons. “Computer Date,” a tongue-in-cheek dystopian deep cut buried in the first and final LP the group would ever release, sees lovestruck futurism juxtaposed with wonky guitars boasting the (hypothetical) undertones of early, demo-ish attempts at soundtracking a rejected Teletubbies motion picture. Lyrically, it reads like the hazy prophecy of a 20th Century hippie who has just been graced with a glimpse of e-dating: “I filled out a form, and she filled out a form. Our data was merged, and love was born! Computer date… the perfect mate… science is great, computer date!” Delivered in part by the Dr. Doofenshmirtz-esque drawl of Richard “Frankie Ennui” Whitney, when the strangely prophetic verses stop, a loony guitar riff takes their stead, traversing amateurish minor scales with the kind of tongue-in-cheek sonic hop-scotch that might play while Wile E. Coyote dies a gruesome death in the dust of his road-running prey. It’s wacky enough to be taken with a grain of salt, but somehow still applicable enough, four long decades later, for the salt shaker to remain untouched on the tableside.

“Suburban Lawns live in a weird online space reserved for figures niche enough to not be on cultural most-wanted lists, but elusive enough for those that do care to dedicate entire, well-followed Facebook pages to causes like “Whatever Became of Su Tissue?””

If not the same exact one, an uncannily similar chord progression graces those quintessential, in-between moments of The Simpsons’ title sequence, wherein Lisa Simpson boisterously saxophones her way into an ousting at the hands of an enraged music teacher, Bart Simpson skateboards through vile pranks on innocent bus-riders, and Homer Simpson winds up surrounded by family on the living room couch seconds after being violently struck by his own car. There is zero confirmation of Matt Groenig intentionally semi-sampling the mystery-laden new wave quintet — let alone even liking their music — beyond a brief period of his life that just so happened to correspond with their short-lived prime. But for the most part, when it comes to Suburban Lawns, confirmation is generally far less a factor than the cryptic mystique that lives where it leaves off. Their story remains, and will always remain, ominously open-ended: the group’s enigmatic lead vocalist disappeared off the face of the earth following their dissolution; an obscure album and an even more obscure 5-track EP represent some of the only direct evidence we’ll ever hear from any of its five members; the band largely isn’t active on social media, though if you count the legions of obsessive followers who romanticize futile quests to “find” them, their shadow very much is. Niche internet subcultures are largely forged by a desire to understand the un-understandable, and it is this trend that has made obscurity marketable — hieroglyphical lingo helps Drain Gang’s cause more than hurts it, Playboi Carti’s lyrical “Cartinese” has graduated from liner notes to Instagram captions, the more esoteric the Doc Martens fit pic, the better — albeit still terminally indebted to a lack of concrete answers. Suburban Lawns live in a weird online space reserved for figures niche enough to not be on cultural most-wanted lists, but elusive enough for those that do care to dedicate entire, well-followed Facebook pages to causes like “Whatever Became of Su Tissue?” The fact that the fabled singer called Su Tissue, nor any kind of fitting culmination for her band writ large, will never be found, is just as eternally intriguing as it is eternally damning.

SUBURBAN LAWNS arose from the forbidding ashes of 1980s Southern California, a doomed, double-edged hellscape that was burning on two fronts: literally, underneath the torches of riots and crack spoons, and figuratively, latched to the kerosene of a burgeoning creative hotbed that was, with mosh-pits as volatile as the hostile music that sparked them, beginning to reflect the locale’s harsh realities. The primitive seeds of the group were sown at Cal Arts in 1978, when art-adjacent undergrads Sue McFarlane, a writer and singer, and William Ranson, a bassist, got together to put their wobbly machinations on wax. In following years, they’d go on to add lead guitarist John McBurney, percussionist Charles Rodriguez, and rhythm guitarist-slash-vocalist Richard Whitney, at which point they’d solidify their outsider’s-rock stature with a series of childishly villainistic monikers — McFarlane going by “Su Tissue,” Ranson going by “Vex Billingham,” McBurney going by “John Gleur,” Rodriguez going by “Chuck Roast,” and Whitney going by the aforementioned Ennui. “I’ve known (Billingham) and John since high school,” Chuck Roast told Vice of the group’s beginnings in a rare 2015 interview, when Suburban Lawns (1981) was reissued by Futurismo Records. “We started jamming in whatever living room or garage would have us, making noise really.”

The group’s nomadic day-to-day was reflected, both sonically and conceptually, by the directionless music that came of it. In a way, Suburban Lawns were nomads in time, searching, but never finding, crevices of history in which they could safely lodge their manifesto, then get back to whatever they were doing before the mantle of apocalyptic prophecy was placed on their scrawny shoulders. On all fronts, they embodied an unsettling brand of anxious, somewhat confused temporal ambiguity — in most pictures you can find of Suburban Lawns performances online, McFarlane is wearing a quasi-Elizabethan smock of some sort, looking in equal part awkward and larger-than-life while her male bandmates sport low-strung guitars over baggy jeans and button-downs — and this is, perhaps, what makes the unsolved state of their mystery a tinge more compelling than its weird internet subculture counterparts. Their air (and in some ways, their sound, too) was that of unsuspecting street corner-lurking teenagers who had stumbled into a UFO by accident, and were now boredly seeking to use art as a vehicle to both make sense of their strange situation, and poke existential fun at it.

It was a sci-fi-evocative selling point that the period they emerged from just so happened to be eating up. From Dune, to the Back to the Future series, to The Handmaid’s Tale, something about the 1980s bred questions about the future that would go on to be answered in varying fashions — whether by way of regressive Supreme Court decisions, self-lacing Nike high-tops, or environmental warfare — but much like The Simpsons, Suburban Lawns’ prophetic legacy wasn’t as much an intentional shtick as it was something that just kind of happened. They were weird, and much like it was for any of the futuristic misfits who starred in the 1980s’ psychic cinemascapes, understanding them was as difficult as understanding the hereafter they embodied. “As hard as it may be to believe, I think she’s really ‘like that,’” one LA Weekly journalist wrote of McFarlane in the 1980s, upon seeing Suburban Lawns perform live. “In other, less tolerant societies, she would be dismissed as a ‘wacko’ or burned at the stake as a witch.” Forty years removed from her brief stint in the semi-limelight, whether this was her fate or not, there’s no way we can ever fully know where (or how) she went.

“The most powerful stan cultures thrive on parasocial relationships. Those relationships are even more parasocial when the thing being worshiped is dead.”

THE FIRST trace of Suburban Lawns’ lore to ever grace airwaves was “Gidget Goes to Hell” a mischievous single that featured, as would all subsequent songs by the band, childish instrumentalism foregrounded by equally-childish — though at some points, profound — poetry. Driven by the sort of simplistic, bass-heavy approach post-punk outfits like the Minutemen would go on to habitually emulate, the track tells the (at first) lighthearted story of the titular “Gidget,” a schoolgirl who lives on daddy’s money, and goes on to wear her “bloody bikini” to hell moments after “flashing white g strap.” Upon release, the single caught the attention of Jonathan Demme, one of several upstart film directors making names for themselves in Southern California’s ashes, and he went on to direct a dingy music video for them, scoring an unlikely Saturday Night Live premiere in 1980. The D-I-Y flick compiled strung-together bits of found footage, compellingly-little effort put toward making any of it appear thought out. Like the song itself, the video, too, came to an abrupt end, this time with the added cause of Gidget’s bloody bikini being an off-camera shark attack.

“Gidget Goes To Hell” was B-Sided by “My Boyfriend,” a semi-urgent romance ballad that simultaneously invokes the Ramones’ “I Just Want To Have Something To Do” and something the Red Hot Chili Peppers might have made in the early 1980s. Much of its lyrical content is left obscure and open-ended, each verse offering a loose hint towards a storyline until, much like poor Gidget, the central plot point comes to a heartbreakingly sudden end. It’s a pattern well exemplified by the track’s concluding stanzas: “Yeah, nobody knows how much I love you,” Su Tissue starts, using the remainder of her spiel to drift indistinctly between speaking directly to, and wistfully about, an unnamed love interest. “He’s my boyfriend / I could never count on him to / I still really want you so.” By the track’s sudden end, the love she speaks of is nowhere to be found, its disappearance explained as succinctly as possible. “You found another little girl. He doesn’t love me anymore. He doesn’t love me.”

It’s difficult, given how briefly their stint in the quasi-limelight lasted, to gauge whether Suburban Lawns ever felt the cultish love attached to their lore today — and whether or not they even care, which they most likely do not, the fact that we ourselves will never know is fuel enough for us to consider them a tragedy. It’s an internet-centric line of logic applicable, somewhat, to the Harambe-influenced meme-ification of niche cultural figures — whether human beings, television shows, or other disparate proper nouns beloved by impassioned online circles — who come to ends either corporeal or commercial, and are immediately deified with poorly-Photoshopped images of themselves entering the gates of heaven. Inherently, the act is more for our comfort than it is for their memory, but we do it anyway, because our ability to live with ourselves is as good as theirs to rest in peace. Really, the dynamic is a low-stakes extension of the funeral writ large. A common maxim run down mourners’ throats by overly-giddy repass preachers is that crying over corpses is a selfish act; rather than appreciate what the dead has done in the world, one weeps over the fact that they will never be there for them, and them alone, ever again. Both the acts of weeping at funerals and Photoshopping dead icons into paradise are, to some extent, self-serving. But perhaps they’re just as necessary. We center ourselves because we only really understand versions of the world in which we are the main characters. Suburban Lawns have entered the territory where, much like Harambe, their obscure legend, never to be understood, is carried by “mourning” devotees who know somewhere in the backs of their minds that the fixed point of resolution they aspire to is actually an asymptote. The most powerful stan cultures thrive on parasocial relationships. Those relationships are even more parasocial when the thing being worshiped is dead.

🛸 🛸 🛸

“Will they breed us just like cows? Will there be some tests to run? We’ll be guinea pigs for fun. Don’t really care if they take us away — as long as we’re back for work Monday.”

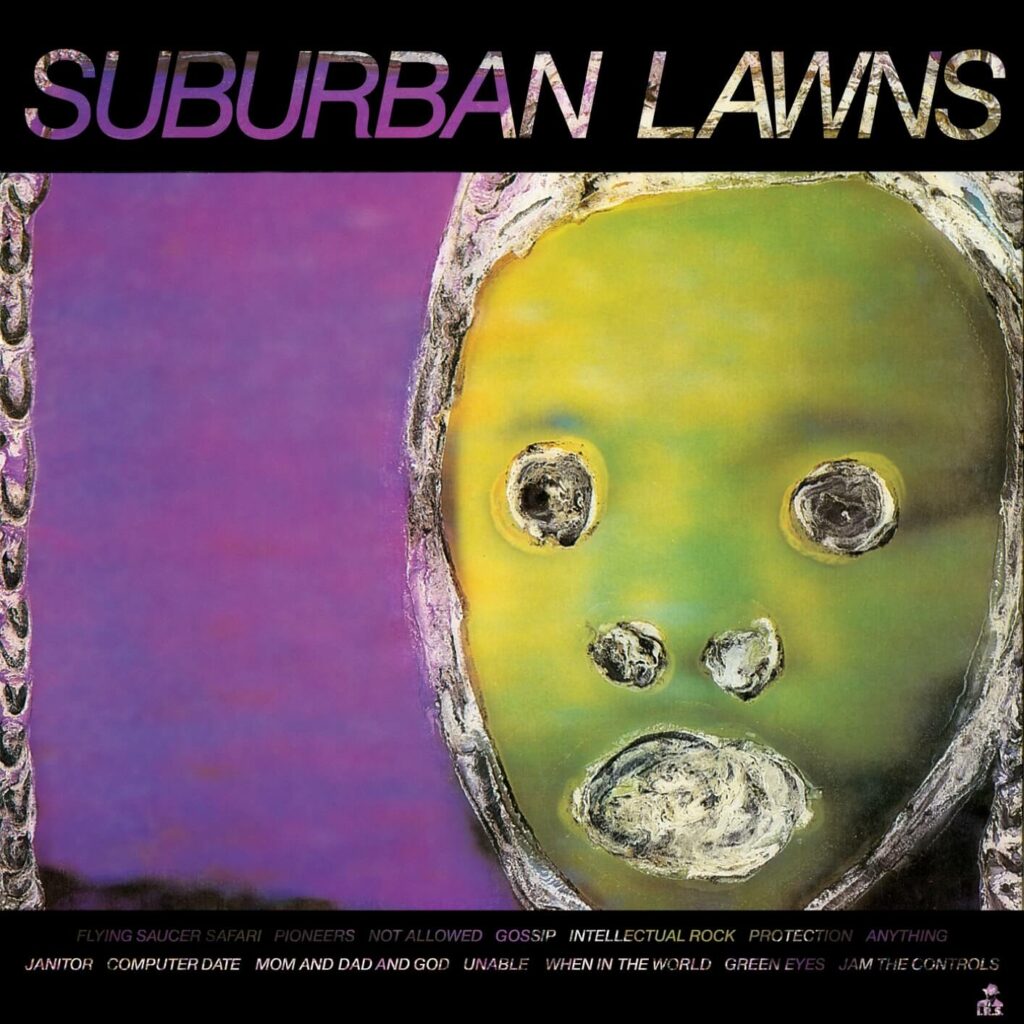

THE sole album ever recorded by Suburban Lawns arrived less than one year after “Gidget Goes To Hell,” tactfully riding the newfound momentum generated by their last project’s wonky, extraterrestrial appeal. In Harlan Ellison’s horrific 1967 short-story I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream, a man doomed to eternal life on planet Earth with a torturous robot is permanently metamorphosed into a mouthless “snail thing” as punishment for the mercy killings of his two companions — and it is something eerily analogous to this, a mouthless alien-snail thing frozen, for the remainder of time, in a jarring, desperate scream nobody will ever hear, that graces the LP’s psychic cover art. Self-titled, and packed to the brim with genre-melting existential mini-treatises, the record arrived with as little context as it did tangible, streamlined messaging. Put together, it bears the hyperdramatic dystopia of Ellison’s primal holler: those scrawny-shouldered, time-traveling teenagers, it seems, might as well be trapped wherever in history they left off, the time machine they arrived in unsalvageably destroyed by a vengeful android.

I first heard Suburban Lawns when I was a junior in high school. My family had just moved from Jamaica, a fabled region of Queens where Subway-side marijuana sales take place bus rides away from high-stakes horse races attended by the elite, to Suffolk County, a drab, racially-monolithic suburbia spanning from the polished ghettoes of Queens’ edge, to the mammoth beachside vacation homes of white millionaires. We fell in Bay Shore, a middle-ground of this geographical spectrum, where star-spangled banners boasting DON’T BLAME ME, I VOTED FOR TRUMP! sometimes hung proudly a few houses down from modest, left-leaning “In this house, we believe…” mantras lazily lodged into dirt-ridden front yards. Suburbia was quickly coming to take on a meaning beyond sitcom television for me, and it was while looking out at the version of it that existed through my bedroom window in September, midway through procrastinating on a lengthy U.S. History reading — probably centered on the struggles faced by Jamestown’s first settlers — that whatever streaming service I was using to scour unreleased rap music shuffled to “Flying Saucer Safari” before I had time to pick something else to play. “Flying Saucer Safari” is track one on Suburban Lawns, and it uses a loose, comic-book-friendly storyline to introduce an unsuspecting gang of curious young people seeking to explore UFOs. Through childish, endearingly-annoying soundscapes that sound like what you might hear in an 8-bit video game, the gang cruises down the barren deserts of Interstate 10 in a station wagon “full of Fritos, Coke and Twinkies, stale Doritos,” scheming to concentrate in silence until they’re able to “psychokinetically” pull one of the extraterrestrial vehicles down for further inspection. This same scene-setting verse is repeated twice, the only difference being the contents of the station wagon. (The second time around, there is now “Taco Bell and filter kings, Correctol and onion rings.”) The last words we hear from the crew are, instead of the lofty answers their plan seemed to promise, more questions. “Will they have protruding brows?” Su Tissue asks of her exo-planetary interests, with a voice that registers like that of an infantile, directionless cyborg. “Will they breed us just like cows? Will there be some tests to run? We’ll be guinea pigs for fun. Don’t really care if they take us away — as long as we’re back for work Monday.”

“Flying Saucer Safari” balanced timeless existentialism with the worldly realities those anti-gravity dreams were bound to, and for both the hormonal version of me that wanted to leave the world — if not just Long Island — and the version of me that couldn’t because he had school on Monday, it became something I knew I lived by, even though I had no idea what that entailed. As is customary for pre-Twitter high schoolers with songs stuck in their heads, the most obscure lyric I could find from it occupied my Instagram bio for some time, and when I didn’t sleep through my train stops, I hummed its chorus on the long commutes from my high school in Queens to home in Bay Shore. Within weeks, another song was stuck in my head, another lyric was in my Instagram bio, and I wasn’t listening to Suburban Lawns anymore.

But two years later, I was a first-year college student in another slightly-bigger suburb called Nashville, and there were deeper existential questions to be addressed — none of which were answered by the classes that claimed to have the answers to them, and even fewer of which were answered by the superficial relationships I sought the answers in, and wound up leaving only with either more questions, or more urgency in finding those asymptotic resolutions. Walking became one of few things that made sense to me, because in retrospect, I thought that if I couldn’t face my problems on campus, maybe using my own two legs to go as far away from them as possible might distract me enough to give the inevitable next problem enough time to arise. On one of those off-campus pilgrimages, I made up my mind on a whim to close the chapter that hormonal high-school me opened, and listen to Suburban Lawns in full. And, as much as it would be so beautiful to be able to write here that it worked and everything fell into place, it really fucking didn’t, and now not only did I have more obscure lyrics in my head, but I also had nowhere to put them, because Tweeting them or putting them in my Instagram bio was now corny — and if that wasn’t the issue, then there was always the fact that I was lost in metro Nashville at 4 AM, and there was a 9 AM class to be woken up for.

“Jam the controls; deny the illusion that we’re eternal, forsake it.”

Much like Ellison’s screaming narrator, and the distressed, unhearable snail thing gracing Suburban Lawns’ cover, I was screaming for answers, with no one remotely close to ever hearing me. The band was, too. “Jam the Controls,” the album’s breakneck, minute-long conclusion sung by Frankie Ennui, functions as a distress call of sorts, begging a recipient who will never be able to help the situation to follow a set of dire, life-or-death instructions. It’s the most confused song on an equally-confused record: lightning-fast power chords from semi-distorted electric guitars are melded together with flashes of intense, dissonant jazz piano; there’s a tricked-out solo squeezed somewhere in the middle that sounds stolen from a sped-up Faith No More demo tape; Chuck Roast’s drumming is a frenzied exercise in erratic cymbal crashing, as if Animal, from the muppets, were taken hostage and forced to play as hard as he could to save Kermit the Frog from gunpoint.

“Jam the controls; deny the illusion that we’re eternal, forsake it,” Ennui rasps, sounding like something has just happened to reveal to him his impending mortality, and little time is left before his clock runs out. In the song’s final seconds, following the aforementioned wonky guitar solo that may have been stolen from a sped-up Faith No More demo tape, he yells Jam The Controls once more, dragging it out until his voice is quivering and infantile, every breath left long withered. Much like Su Tissue and his band at-large, it’s difficult to tell whether he was zapped by a UFO, abducted by aliens, or just tired.