FULL BLEED

Is it still sports photojournalism if it isn’t a sport?

SAMUEL HYLAND

To qualify for inclusion in Best of Photojournalism, a yearly contest-qua-anthology established by the National Press Photographers Association, an aspirant lensman might have been considered for six categories: (1) International News, (2) National News, (3) World Understanding, (4) Features, (5) Sports, or (6) People, Portraits, (and) Personalities. Published on the first day of 1980, the collection’s 15th edition — especially in retrospect — feels apposite for an America freshly infatuated with boundary-breaking, and barrelling towards a decade synonymous with it. Perhaps even more so then than now, athletic feats were representative of subversion both nationally craved, and desperately rallied behind. As fledgling technologies sputtered, and often to devastating effect, the brute force of a human body testified to a twisted meritocracy: if an American figure could do the impossible on live television, well shit, maybe America could, too. And so, in that year’s Best of Photojournalism anthology, a densely-packed sports section foregrounded cinema-ready feats — like F1 drivers nonchalantly escaping mini-mushroom clouds, or dramatic near-deaths at the hands of 200-mph hydroplane speed-runs. The edition’s winning athletics photograph saw a diver stanced like an eerie crucifix, fiery fog dancing along the contours of his stoic, Christ-shaped frame.

“And call the cops in the meantime if you’re that passionate about it. But I’m passionate about what I do, too.’’

The first photo in the sports chapter, following a brief essay, is of a nascent skateboarder covered in pads, mid-trick. “No, this picture is not upside down; but the young athlete on the skateboard is—and in midair!” its caption reads. “Kelly Finn is demonstrating the form that won him top national ranking among thirteen year-old skateboarders.” Over four decades later, the image feels almost hilariously geriatric, like something ABC shot-callers might write into a Goldbergs episode for added nostalgic effect. One hockey-gloved hand on his board, and the other on the bowl’s edge, the young skater’s knees are up to his face; look hard enough, and you can make out a hoarse coach shouting something about “beautiful form.” Ask a Tompkins regular, though, and the image might feel outdated, if not unimpressive, for other reasons — high among them being its lack of immediate danger. If the iteration of skating that won over U.S. hearts, then, was defined by preset courses, willing audiences, and football pads, the scroll-friendly standard hinges more on disruption: unpredictable streets, unwilling audiences, and precise skill, not padding, being the lone protecting agent for vulnerable bones. The spectacle is just as much what’s accomplished as what lies at stake.

Though skateboarding’s protected 20th-Century model lives on in lofty spaces, like the Olympics or the X Games, its champions often find themselves shrugged off in comparison to street-dwelling counterparts. Last winter, when the flagship skate magazine Thrasher held voting for its annual “Skater of the Year” award, three of four finalists were open-world skaters, while the outlier, Nyjah Huston, had garnered much of his acclaim on the arena circuit. When Supreme’s Tyshawn Jones was crowned the winner, his victory raised questions about metrics, particularly regarding whether skating had become a “popularity contest.” But in a very literal sense, perhaps to the chagrin of formalists, “popularity” might be the name of the game, after all: conquering a populous terrain, where people and obstructions are part and parcel, speaks more loudly to an American meritocracy than, say, having one’s path carved out. Skating for the common man equals skating among the common man, and if you can conquer his territory, you can conquer his respect, too. “You just work here, you don’t have authority over me,” Jones told the New York Times of his attitude towards security guards, in 2019. “You don’t have a gun, so you’re not gonna make me leave. I’m gonna do this trick; you’re gonna watch. And call the cops in the meantime if you’re that passionate about it. But I’m passionate about what I do, too.’’

For his 2022 “Skater of the Year” Victory, the trick that seemed to give Jones a final push was a backside flip—a slightly more complex version of the kickflip—over a gap at New York City’s 145th Street Subway Station. When the clip premiered across Supreme’s social media channels, it felt something like a preemptive victory announcement: an effect conjured, in part, by the overwhelming sum of footage that accompanied the money-shot, like damning exhibits in a court hearing. In a lengthier Instagram reel that followed the initial premiere, hasty fishbowl-cam recordings saw a determined Jones flanked by hooded associates, marking up platforms and out-maneuvering suspicious cops. Also included across the footage, perhaps most convincingly, was an exhaustive series of failures. Supreme stakes its productions in quotidian realities, and maybe it’s what makes Jones such a snug fit for its urban brand: he knows how to navigate the trivial well enough to make it interesting, if not mythic. 2022’s “Skater of the Year” victory was his second; during his first winning campaign, in 2018, he covered Thrasher with a death-defying ollie over the 33rd Street Subway entrance. In both cases, a wrong move may well have led to career-ending maiming, or a very painful (and public) death.

“The way I walk down the street and smoke a cigarette is just as important to me as the way I skate.”

Jones would be far from the first skater to capitalize on New York’s grand, unforgiving appeal—another debate sparked by his 2022 SOTY win: are we placing too much weight on regionalism?—but something about his no-holds-barred approach, no less Supreme’s at-large, makes his legend feel loosely achievable, whether to Quartersnacks-subscribed couch potatoes or fledgling athletes looking to conquer their own respective roads. “I want the viewer to feel like they are there,” William Strobeck, a longtime Supreme videographer, told 032c in 2019. “I want them to feel like they are a part of our crew and see what it’s like from an insider’s point of view. I want them to walk away and wish they were a part of it.”

Maybe another crucial difference, between the 20th-Century skate model and our own, is that the I-wanna-do-that-too effect extends far beyond athleticism. Street-skating in the 1980s, much like the punk subculture it mirrored, was marked by outerwear more utilitarian than public-facing: a skater bought cheap clothes, ruined them, bought more cheap clothes, then ruined those. Interestingly enough, and to the ire of older skate purists, Supreme has grown, over the decades, into a torchbearer for the exact opposite trend — one where pro skaters are gifted fancy pieces by their respective companies, videotaped in them, and effectively rendered advertisements for an all-exclusive winner’s club. You may not be able to skate well, the industry’s selling point insinuates, but purchase this reflective puffer jacket for $350, and you’ll look just as cool as someone who can. Among Supreme’s most effective image-first characters is Sean Pablo, a lanky California skater who glares menacingly, hosts strange visual art exhibitions, and soundtracks his clips almost exclusively to off-kilter shoegaze. In his case, more often than not, it seems as if skating is weighted equally (if not secondary) to the punk-informed image he proffers to aspirant teenagers, one hand on unused HOCKEY decks, and the other in their mothers’ wallets. “The way I walk down the street and smoke a cigarette is just as important to me as the way I skate,” he told me in an interview this past February. (He spent our conversation extremely high, until he got bored and asked for permission to queue Earl Sweatshirt songs for the remainder of the allotted time.) “Even though that sounds kind of vapid. I’ve been a skater my whole life. I’m aware of people looking at me. I’m putting on a show for people all the time. It’s kind of fun.” Whereas an Olympic skater is more or less limited, culturally, to the confines of a course, street-skating seems able to breed bona-fide artistic entities: whether the art exists in line with the skating, or diverts from it, the effect is one of both layperson appeal and strange guerrilla marketing.

As of the writing of this piece, the most recent movie uploaded to Supreme’s YouTube channel is “Piggy,” a shorter-length feature by Strobeck with appearances by a number of street-skate heavyweights — Caleb Barnett, Troy Gipson, Kader Sylla, Sully Cormier, and Ben Kadow, among a slew of other names likely to appear in your local box-logo wearer’s IG following list. The film’s most effective moments, aside from its galore of eye-popping maneuvers, are the ones where countless failures amount to bloodied hands, anguished grunts, and eventually, for maybe five seconds, something skate-related that actually goes right. During one interval in particular, Nik Stain, a brash skater with ties to Hockey and Limosine, shouts through an unforgiving gauntlet of tries to land an ollie over a boardwalk. When he finally gets it, the moment is revelatory, but only for the five or so seconds preceding the next segment. As much as reality inherently sprawls, it’s difficult to squeeze its longform crux into 30 or so minutes, especially when said 30 or so minutes are to be shared with about fifteen other skaters, and countless other tricks. Supreme, let alone the skate-shop-to-cultural-entity pipeline it foregrounds, faces similar challenges: exist as everything at once, and at some point, the task of downsizing one of those things becomes unavoidable. Ask any teenager what Supreme was in 2015, when it made thousands of dollars on logo-imprinted bricks, and skateboarding may not have come up at all. Compare that to the skate vision of Best of Photojournalism 15, and depending on who you ask, it’s either Kelly Finn’s greatest dream or worst nightmare — while he was outgrowing his pads, skateboarding at-large was, too.

🛹🛹🛹

“They’re their own figures. I want them to do things however they want. I’m just there to document it and tell them if I think they’re screwing up.”

Aside from 30-second film outtakes, the most popular media items on Supreme’s Instagram—and probably some of the most important media in skate culture—tend to be lookbooks. A few months ago, the conglomerate unveiled its 2023 Fall/Winter Collection over a lengthy series of posts, modeled by familiar pro skaters and the occasional surprise cultural figure (Jadasea, RedLee, NBA Youngboy). Among the most expensive pieces was a dark puffer coat, emblazoned with an eerie photograph by the late downtown documentarian Dash Snow. Titled “Hell,” Snow’s photo was of a Shell gas station at night, its “S” either worn out, or strategically removed post-hoc. Before his death of an overdose in 2009, Snow garnered a reputation for capturing the New York elite at their ugliest and most decadent; in a photo displayed at a posthumous solo exhibition, a half-naked woman hoists a painting in a room cluttered with candles, wine bottles, and a human skull. The skate-image landscape heralded by Best of Photojournalism 15, where athletic prowess reigns supreme, feels one-dimensional for more reasons than padding, preset courses, or even the 13-year-old subject. The most effective skate imagery isn’t so much about skating, anymore, as what the skaters are doing when the boards are away. It falls on the photographer, the same way it fell on Dash Snow, and the same way it continues to fall on the William Strobecks of the extended street-skating universe. Kelly Finn wins the trophy regardless of whether the cameraman is present; Tyshawn Jones does not.

Part of what makes Strobeck effective, especially as a mascot for skateboarding’s 21st-Century iteration, is that his documentary practice extends beyond the streets of his clients. Over the years, it’s become something of a rite of passage among New York skaters to be photographed in his apartment, usually against a very specific wall. A scroll through his mythic Instagram page yields headshots of ossified legends and up-and-comers alike, posed with various props—a bicycle, a baseball bat, an open flame, a Madonna vinyl—and usually side-by-side with peers. “They feel comfortable enough to be themselves. If we were to send another filmer out that they didn’t know, they’re gonna be closed off and wonder, ‘What does this guy think of us?’” Strobeck told 032c. “Since I’ve known them since they were little, I’m more of a big brother. I’m not giving them orders. They’re their own figures. I want them to do things however they want. I’m just there to document it and tell them if I think they’re screwing up.” Though the “proper” way to document street-skaters seems to change every five years — name-search “Strobeck” on Twitter, and you’re likely to find a vigorous critique within five tweets — an overarching principle, now, seems to be giving athletes room to transcend athletics.

Nearly ten years before Tyshawn Jones’s 145h Street stunt, street-skater Koki Loaiza ollied over the same exact subway gap to much less cultural uproar. The fallout was markedly different for both skaters—while Jones was granted his second “Skater of the Year” trophy, Laoiza was the subject of tabloid clickbait (Mind the gap! Daredevil skateboarder leaps between subway platforms in incredible late-night stunt). But even beyond their vastly different legacies, the connected tricks share a gritty lineage of New York street-skating’s relationship with documentation, especially when said documentation is just as daredevil as the feat being documented. (Both tricks were recorded from the train tracks, by videographers who had to jump to safety at the sound of oncoming trains.) This past February marked the tenth anniversary of Full Bleed: New York City Skateboard Photography, a dense photo-book comprising the work of over 40 photographers, and spanning three decades of on-the-ground action shots. The publication poses interesting contrasts to Best of Photojournalism, for one, because the brand of skateboarding it recalls is mostly criminal: whereas the NPPA’s notion of impressive skating was limited to legal confines, Full Bleed is more interested in radical disruption, where instead of conforming to man-made arenas, human bodies vandalize urban ones. Content-wise, Full Bleed also differs in that it may not even be so much about capital-S skateboarding at all. In some of its most compelling images, subjects aren’t taking to the streets — they’re standing in moonlit parks, fraternizing on brownstone staircases, mounting yellow taxis. In the majority of images where skateboarding does occur, traces of artistic intent peek faintly, albeit convincingly, through the cracks. A standout of the collection sees skater Qlon Douglas ollie towards the distant World Trade Center; his T-shaped figure is bathed in crimson, a crucifix not unlike the diver in 1980’s winning NPPA sports image.

“What is thus displayed for the public,” he wrote in that piece, “is the great spectacle of Suffering, Defeat, and Justice.”

Between skating’s past and present lies a question about art, athleticism, and when (or whether) one should be allowed to bleed into the other. Sports and art often operate hand-in-hand — mostly by mistake, and only to those intent on drawing those particular connections. A convenient modern example is to be found in @ArtButSports, a Twitter account that takes screengrabs from in-progress sporting events, and matches them with near-identical artistic analogs. (In a recent tweet, a chokehold by Draymond Green was likened to Andrea Solari’s 1507 The Head of Saint John the Baptist on a Charger.) Reach even farther back into the sports-arts canon, though, and Roland Barthes emerges as a distinct precursor to skating’s decades-spanning middle-ground. Among the most oft-cited essays from his Mythologies, a book-length collection of cultural mini-treatises, is “The World of Wrestling.” “What is thus displayed for the public,” he wrote in that piece, “is the great spectacle of Suffering, Defeat, and Justice. Wrestling presents man’s suffering with all the amplification of tragic masks.(…) It is obvious, of course, that in wrestling reserve would be out of place, since it is opposed to the voluntary ostentation of the spectacle, to this Exhibition of Suffering which is the very aim of the fight.” Barthes penned the essay as means of distinguishing wrestling from boxing — a debate that continues to dominate America’s break rooms — but in doing so, also provided a loose framework for sporting entities that walk similar tightropes. One might play a game to win hardware; one might also play a game to win souls.

If arena-skating finds an analog in boxing — a score-driven contest marked by explicit confines — then street-skating falls more in line with Barthes’s wrestling, more intent on garnering swag points (or suffering points) than skill points. A common rebuke, from boxing purists, contends that professional wrestling is inauthentic: “You do know it’s fake, right?” But much like the WWE, though open-world skating tends to put entertainment before formality, there’s no denying that the art, even if foregrounded, is only possible through athleticism. Nearly every full-length Supreme video can be split into thirds: one-third banter among homies, one-third tricks being failed, and one-third tricks actually being landed. Perhaps the first two factors are tolerable, let alone widely acclaimed, because skating at-large has undergone a transition novel in American athletics: while no other sport is comparably split between a formal iteration and an art-forward one, not only is it a battle in skating, but the art is winning.

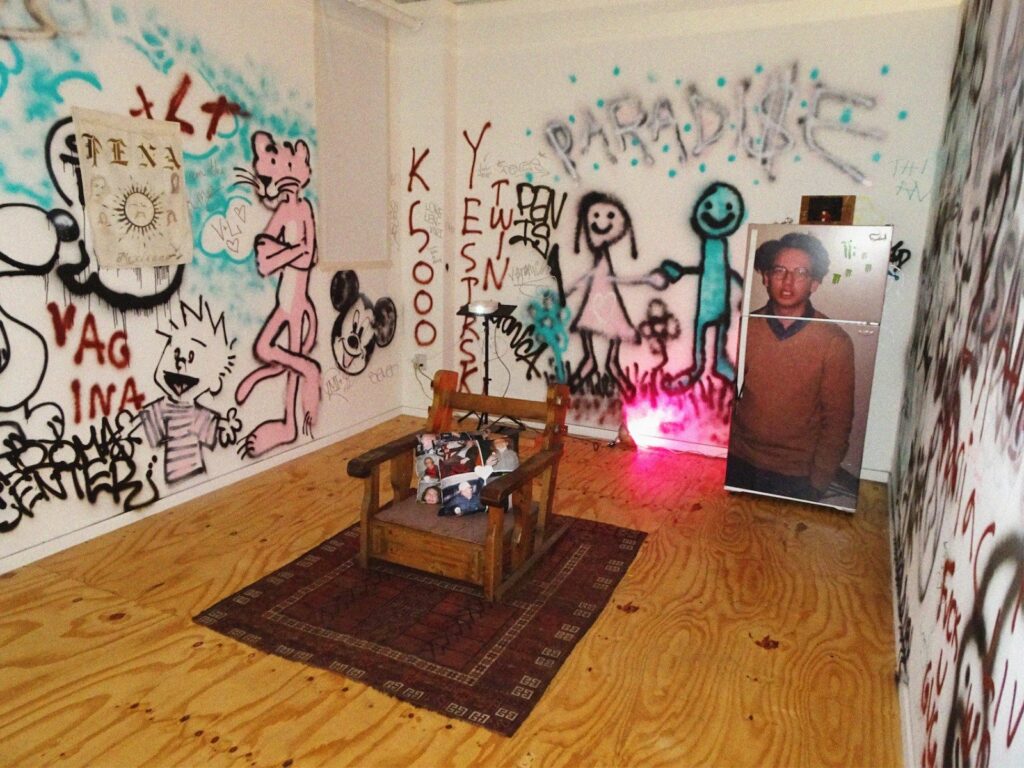

About a year before my aforementioned interview with Sean Pablo, I met him in an upscale hotel lobby somewhere on the Lower East Side. A grueling road accident had left him sidelined from skating indefinitely — as of this writing, he has yet to make an official return — but he’d been occupying himself with a newfound focus on his artistic practice, set to culminate in a debut solo exhibition slated to open in Chinatown that night. “Hopefully it can convey my life, and the way that I… see stuff,” he said, clutching at his crutches. “I don’t know, honestly. It’s really hard to say. What I want people to think? I don’t know.” As much as his terseness likely stemmed from vague disinterest, it’s fitting rhetoric for the sports-as-art vanguard he embodies. Supreme, nor any of the skate conglomerates like it, will never explicitly state its intentions, nor guide its consumers as to what they should be looking for. You come for what you think you see, and stay for glimpses of confirmation — not in short supply, perhaps, for a cultural entity intent on being both insular and everything at once.

That night, at a rickety upstairs gallery a few blocks away from the hotel, it was interesting to see high-school kids, boards in hand, confusedly ambling through their first-ever art show. When their hero arrived on his crutches, they circled around him nervously, as if they wanted to say congrats, but didn’t necessarily have the art-school vocabulary to do so. Decades after skate media allayed an America obsessed with boundary-breaking, it was skate culture, no actual skating necessary, that seemed to be breaking through the barriers. Though his lack of padding may have cut his career short, Sean Pablo remained a fixed cultural entity: one who, like Supreme, was interesting both on and off the street.