EVERYTHING IS MEDIUM

A humble art-maker seeks out the middle of the universe.

SAMUEL HYLAND

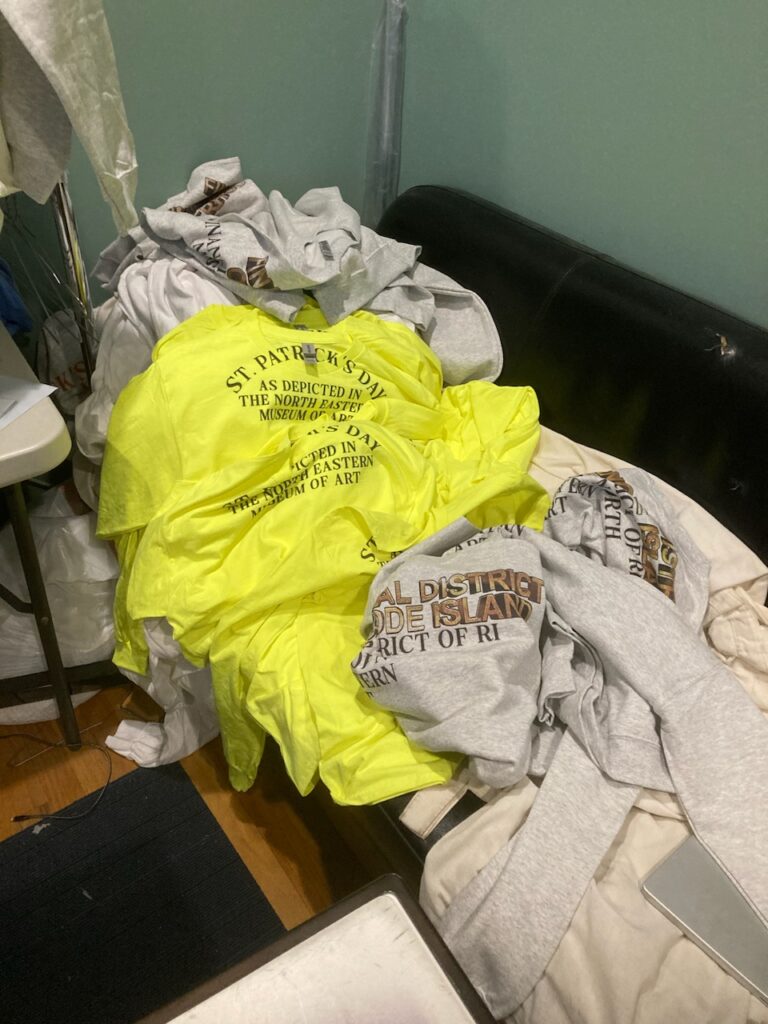

A recent collection from The Blank Traveler, Adrian Tiu’s contextless online fashion outlet, comprised a uniform litany of heavily-branded sweaters — most in commemoration of St. Patrick’s Day, and nearly all sponsored by the “Museum of North Eastern Art.” It’s worth mentioning that the Museum of North Eastern Art doesn’t exist. Nor does its inaugural St. Patrick’s Day exhibition, which was advertised, quite convincingly, on a sleek neon-green promotional long-sleeve: “ST. PATRICK’S DAY / AS DEPICTED IN THE NORTH EASTERN MUSEUM OF ART,” a block of authoritative serif-text declared across its chest, flanking what looked like a distressed, ghastly humanoid. Last November, when I purchased the sweater on a whim, it was partly because I couldn’t tell whether it wanted to be worn or displayed. The arc-shaped “ST. PATRICK’S DAY” on its upper region was positioned slightly too high; the text broke away at the neckline, bled into the inner section, then re-emerged on the other end, as if to feign intactness. The few times I’ve worn it on the subway, I’ve imagined curious eyes burning a hole through the unfinished sentence, a human neck breathing where letters should be. Its completeness as an object is better realized in solitude — on a wall, on a website, in a frame — than on someone else’s body.

Tiu is obsessed with murky middle-grounds like these: less about being one thing or the other — streetwear or fine art, plain or confusing, existent or nonexistent — and more about reckoning between extremes, tethered to their centers as if stuck between two magnets. One recent evening in December, he was holed up in a homely Upper West Side apartment, the kind you see in sitcoms about troubled 20-somethings navigating middle-grounds of their own. A fresh graduate from the Rhode Island School of Design, he’s birthed far more cool ephemera, especially for his age, than he’s often willing to talk about. (Among this ephemera: an album cover for Mavi; motion design for Jimmy Kimmel Live!; a forthcoming art book out via Full Court Press.) But perched in his living space, despite being surrounded by an army of physical, self-made art objects glaring down at him from shelves, he seemed much more interested in appreciating innovation than taking credit for it. He wore a plain white T-shirt with blue jeans and sat cross-legged, speaking in jittery, thought-out sentences. “The thing about a Gildan tag is that it’s a tear-away-able tag… they want you to tear it away and put your own brand in it,” he said between sips of water, staring through wire frames the way a tortured artist would. “I don’t. I want to problematize a lot of different avenues of art with my project. And one of those avenues is the streetwear culture of branding.” Seated across from him in my brand-new “North Eastern Museum of Art” long-sleeve, it was maddening to picture someone who’d much rather invent — and vigorously promote — several fictional companies than claim any of their spotlights for himself.

Such world-building is a time-tested tactic for elusive artists, particularly ones who create more than they’re able to fit under one identity. Among these artists is Dean Blunt, the most tormented person you know’s favorite avant-pop provocateur. Below, you can read a conversation about why Tiu resonates with him, the pitfalls of box logo theory, and the social lives of art-school introverts.

SAMUEL HYLAND: (Gesturing towards tape recorder) It’s a TASCAM DR— I don’t remember the code, but I got it for Christmas one year. I’m recording on my phone too. I always make sure to double up.

ADRIAN TIU: I’ve dabbled in the interview game.

You seem like you’ve dabbled in everything. Tell me about your dabblings in the interview game.

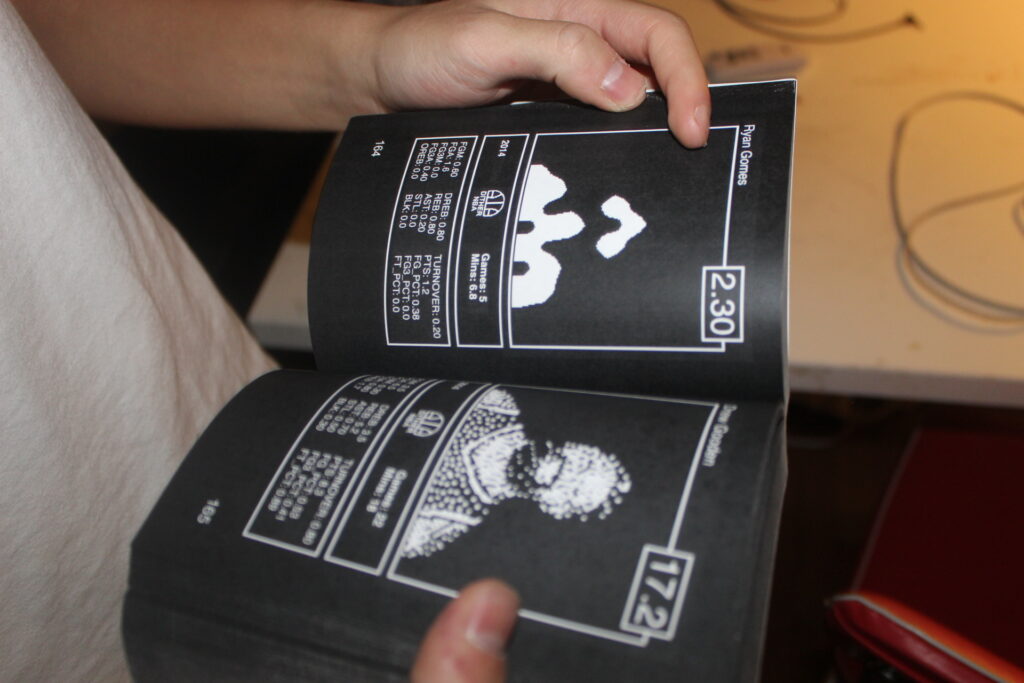

Me and my girlfriend run a magazine. Let me give you a copy. (Fetches copy from bookshelf). This is our fourth issue, our most current issue. We interview artists and non-artists. My girlfriend runs it more, but I just help out with design and conduct a few interviews here and there.

How do you guys get contributors?

It’s just the two of us.

This is the most well put-together magazine I’ve held in my hands in so long. You have multiple streams through which you interrogate art, and you’re doing them all at a very high level. How does this start? When did you know that you loved art and wanted to pursue it?

As a kid, I did a lot of drawing. I took a few art classes in high school, but was definitely interrupted by academia — being studious and trying to get into a good school. Probably like sophomore year, I started maybe painting. I started painting really late. Even now when I paint, it’s more like drawing. I don’t paint like a painter. Painters typically block out shapes, and shadow and stuff, as opposed to more… line work, if that makes sense. I’m definitely much cruder and just throwing stuff around.

Can you say one positive thing about your painting?

Is this, like, a personality test?

When I asked you about drawing, you hesitated to start talking about painting. And when you did start talking about painting, it was to say that you were more crude than oil painters.

I don’t think I mean crude in a negative way. I like how I paint, more than a lot of other painters. I mean crude in a good way. So that’ll be my positive thing. I’m crude. I paint quickly, which is a good thing, because that means I can paint more things.

True. Okay: so you have drawing, and you’re starting to paint in high school, but academia is beginning to infringe.

Yeah, like math. Getting good grades… I mean, I didn’t want to go to art school. I applied to RISD, and maybe Pratt as a backup, for if I wanted to go the art direction. But mostly it was non-art schools. My art portfolio was more of a supplement to my report card. Like, I can do this, too. It was my debate club.

What made you decide on the art-school route?

I think RISD gave me the most money, and I was like “Fuck it, I’ll just do it.” The first year was super rough, and I wanted to transfer. It was just the curriculum — it’s “foundation year,” so it’s a bunch of super long, drawn-out classes about charcoal drawing and shit. I was like, “Fuck… This sucks.” There were 8-hour classes every day, and they were required to give you 10 hours of homework every week.

At what point did you start enjoying it?

Probably when I got into graphic design, so the year after. I wanted to learn new skills. Drawing’s intuitive — you don’t learn any techniques in drawing class. I mean, that’s how I went through high school. Every class is to learn. Like, how to solve a problem, or break down a fucking atom or something. Up to that point, education was a utilitarian thing, where every moment was to expand your skill set, and use that skill set to do a job. It was a crazy switch-up when I got to RISD, where you just kinda did whatever you wanted to do. And then there were these crits who judged you.

What is a “crit”?

Critiques. Like, instead of tests, basically.

So you would have to present your work in front of a panel?

Just the class. Every week, you’d come in with your homework and present it in front of your class, and everyone would get feedback from the teacher and stuff.

Were you getting violated?

Yeah. Your classmates kind of mirror the professor. They want to match the energy to fraternize with the teacher, a little bit. So if the teacher is harsh, everyone’s gonna lean on the harsher side, and vice versa.

That’s like, movie shit. Tortured art student presenting to a class of very critical peers, all foaming at the mouth and yelling shit like “Your work lacks the gestalt!”

It’s such a crazy switch-up from normal academics. When you’re taking a typical test, you’re judged only by your teacher, you do it by yourself, and you’re the only one who sees your grade. When you’re in a critique, everything is public. And RISD’s social life revolves around who’s a good artist and who’s not a good artist. People will judge your character based on how good your art is, and how good of a critique you’re getting. It’s not like you can leave class and live another life. Everyone hears about everything. It’s a small school.

Was it your original intention for your art to be something only you saw?

Yeah. That’s why I didn’t fuck with the first year, because it was so jarring how public everything was. Art, to me, was always something you did at home, by yourself, at your desk. Drawing is such an isolating thing. Painting is, too. The idea of even sharing a studio space is… impeding. When you’re doing art, it’s an intimate thing.

What makes it intimate?

You’re dealing with such personal things, and you’re thinking about a lot of stuff, and you’re rehashing a lot of traumas, if you’re making something worth telling. It’s hard to do.

I wonder where clothes fit into all this. The North Eastern Museum “St. Patrick’s Day” long-sleeve succeeds as an object on its own, but you can’t read it properly when it’s on someone’s body. Are you looking at the clothes you make as art or fashion?

The clothing “brand,” if you want to call it that — I started that in high school. My parents print T-shirts for a living. They have a company where they print souvenir tees, like “New York, New York: Established in 1650” tees. So as I’m growing up, the whole print shop’s in the crib, we have four printers, and they’re the first thing you see when you walk into the house. All these fucking printers, all these shirts, it’s a fucking mess. I’d worked for them since, like, middle school. Just printing shirts. The whole root of their thing is commerce. That’s all I knew. So when I started to do art, and started wanting to put my art on T-shirts, it was with that intention: to make money.

A lot of the early stuff was… not necessarily cash-grabs per se, because I didn’t make much money off of it. I’ve never made much money off of it (laughs). But it was definitely consumer-oriented. “Trendy.”

Do you have pictures of some of the old stuff?

You don’t want to see them. I had just found out about streetwear. Sophomore year of high school, 2015 maybe. It was all fucked. Totally fucked. The audience was just people from my high school.

Where did you go to high school?

It was called Cambridge Rindge and Latin School. It’s a public school in Cambridge. It was, like, the only public high school in the area. Everyone went there. It was pretty big. (“Eternal Condition” by James Ferraro plays on a nearby speaker.) This is very Dean Bluntian.

He’s one of my favorite artists. I was obsessed with him for, like, two years. I just got out of it.

Dean Blunt’s great. I like his more melodic stuff. He did a soundtrack for Burberry recently that I thought was great. “death drive freestyle” is a great song, too.

Deadass. But you’re going to high school in Cambridge, and you’re making this vapid, empty streetwear.

Complete bullshit. I wasn’t thinking at all.

When did you start thinking?

Probably when I went to art school, and I understood the narrative of art as an entity, and I could comprehend the different conversations artists were having.

Can I ask — what does “The Blank Traveler” mean?

Again — it was a name that I had come up with, because I thought it was cool. It was literally just words. It doesn’t mean anything. I was empty-headed.

And you don’t want to change it?

No, because it’s an homage to that time. I acknowledge that it happened. It’s going to evolve. The context is what matters. But I do hate referring to it by its name. I just say “I make T-Shirts,” or “I have a T-Shirt company.” That’s why I don’t put “The Blank Traveler” on anything.

I’ve noticed that. There’s the St. Patrick’s Day Stuff, then the Museum stuff… where do all of these references come from?

Originally, the “brand” was a real clothing brand. I wanted to sell shirts and stuff. Then, when I went to art school, I discovered what art was, which is understanding abstraction and doing things out of your volition as a human being. So I learned what art was in art school, because that’s what you pay all that money to do there. And that’s when The Blank Traveler started becoming more of an art project, as opposed to a commerce project. As far as the St. Patrick’s Day stuff and the Museum stuff… I have an answer, but I just don’t know how to— can you ask me something else? And then we can build up to it?

There was a sculpture project you did some time ago that I think sort of relates. It had to do with basketball courts, and it was in memoriam of a school. Can you tell me about that?

Those were courts that I would play basketball on. They got destroyed. They were part of a school that my house was literally across the street from. They’re rebuilding the school, essentially.

And the courts suffered in the process?

They’re not coming back. They’re rebuilding the school, but not the courts. (Laughs.) But I didn’t make those to be like, R.I.P. to the courts, or whatever. I was just observing what was happening. I wanted to be separate from it, to look at it.

I guess it sort of ties into (The Blank Traveler), because everything’s hyper-local for me. Everything is referential, in terms of where I’ve been, where I’ve lived, and the cultures of these… not “weird” towns, but off-brand towns. Providence and Cambridge aren’t mainstay cultural hubs. They’re caught between Boston and New York. But I look at them, and I see them as a more interesting thing than they probably are. I romanticize them a little bit. All of it is me romanticizing mediumness. Everything is medium. The “St. Patrick’s Day” thing, for example — there’s a huge Irish immigrant population in the greater Boston area, which is why the team is called the Boston Celtics. The shirts were an homage to that. And then the “North Eastern Museum of Art”… I’m making up these “sub-brands” to my “brand.” It’s an entirely fake brand.

That’s very Dean Bluntian.

I resonate with Dean Blunt, because he’s got all these different identities. He’s got Hype Williams, he’s got Babyfather, he’s got Dean Blunt. Even if you saw that (“North Eastern Museum of Art”) shirt, there’s no fucking tag. You wouldn’t be able to find where it came from if you found it in a thrift store.

Do you desire to not leave a trace? Let’s say you die. When people see your work, do you want them to be like This is Adrian? Or do you want them to be like This is a cool object?

Probably just a cool object. That’s part of the reason why I leave the Gildan tag in. It’s not me being lazy. The thing about a Gildan tag is that it’s a tear-away-able tag… they want you to tear it away and put your own brand in it. But I don’t. I want to problematize a lot of different avenues of art with my project. And one of those avenues is the streetwear culture of branding. Being so ego-driven that you have to do that.

Supreme shit.

Yeah. Tearing away a tag and putting your own tag in it is such a box-logo action. That’s my “artsy” statement on streetwear. I don’t want to brand something. I just want to make cool-looking shirts. But on the other hand, I do like that (The Blank Traveler)’s a “brand.” It’s kind of an untapped, overlooked medium. When you look at a brand, the first thing you think of isn’t “what artistic statement are they making?” So I guess I want it to sit between the art world and the “brand” world, as pretentious as that sounds.

You’re pretty obsessed with in-betweenness. Medium towns, mediums between art and streetwear—

And art and design, and all of that. But at the same time, the art world is so… I’ll use RISD as an example. At RISD, all the young painters— they’re making brands with their paintings. The way to sell art, or paintings, now, is to have a “thing.” Maybe you paint skulls or something. You have a motif that’s super Instagrammable, because everything is on Instagram. The directors of these galleries are on Instagram. They’re gonna make or break you. So at least based on the RISD model, it’s all about marketing to a platform. But they’re so coy to admit it. They’re not honest. They still think they’re above you because they’re doing paintings. Yet in all practicality, they’re running a brand. I think it’s much more honest, and apparent, to be like “I’m making a brand, and one of the main goals is to make money.” I don’t want to be a brand. But I want to make money.

I get it. The worlds you’re operating between, of streetwear and fine art, are each extremely pretentious in their own ways. So you’re running away from both of those pretensions, and that’s leading you to an eternal middle.

Exactly. And the “medium,” for me, is a sort of artistic motif, because there’s this return to childhood. With a lot of painters, the main part of the image is nostalgia, or trauma, or something. Growing up making T-shirts — this is literally the only medium that pays proper homage to me as a kid. It’s deceptive for me to make a painting of my childhood, because it doesn’t honor me as a kid in the same way that making a T-shirt does. I don’t expect people to look at the brand and think like you, like “This is an art piece.” I still want the image to be cool enough for someone to buy, though.

Where’s your parents’ house?

Cambridge.

You’ve told me you don’t have a studio. Is that still where you run this operation out of?

Yeah. I time my “drops” around when I’m planning on going back, which is usually around holiday season. I stay there for whatever amount of time, print everything there, and ship everything from there. So everything is dependent on me going back to Cambridge, and literally, returning — like a homecoming. Not to say that people are rejoicing in the streets (laughs). But even to this day, a lot of my customers are from high school, and will pick up their orders from the house. I’m leaving there within the next few days, and I’m going to stay there for a bit.

Then what’s next for you?

What’s next for me… is this the last question?

Yeah.

And then the interview’s done?

Yeah.

Damn.

Think long and hard. Think deep. Make it count. All the pressure in the world is on your shoulders.

Um… I’m gonna go to Cambridge and print these shirts.

You can learn more about Adrian Tiu here, and purchase from The Blank Traveler’s new collection here.