🤖If time is money, free time is free money, and neither of those things exist.🤖

SAMUEL HYLAND

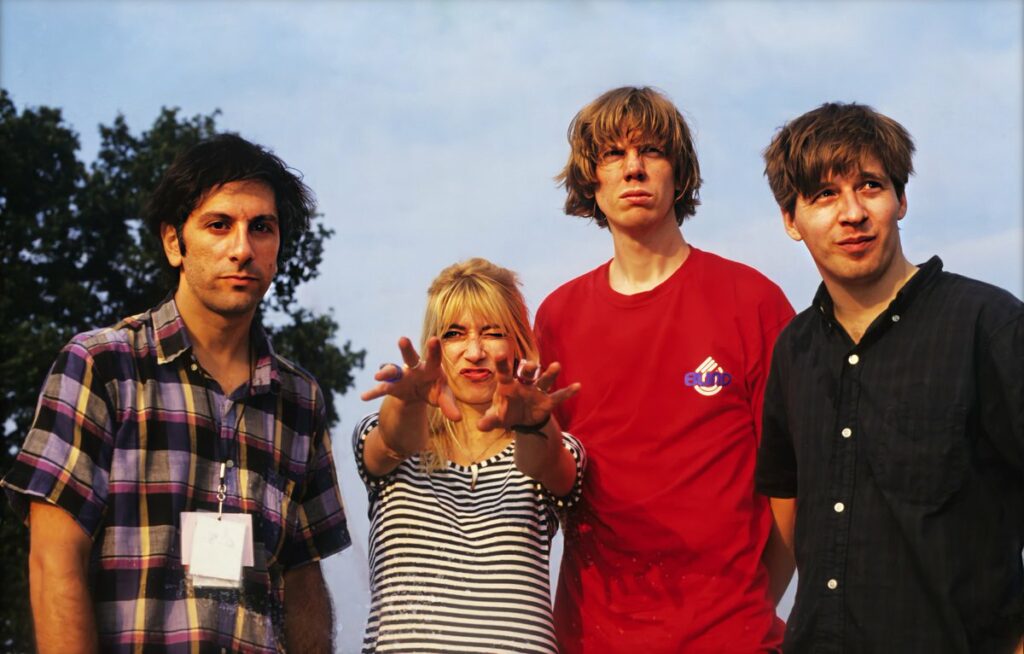

Midway through “Female Mechanic Now On Duty,” the seven minute-long third track on Sonic Youth’s unwieldy tenth album, screeching Jazzmaster distortions go eerily silent, and Kim Gordon talk-sings as if under a spell. “Modern women cry; Modern women don’t cry,” she drawls, the way someone drooling before a pendulum might. “Cry don’t cry / You hurt me with your lie. (…) Make believe and I believe Perfection is a…” In similar spirit to Gordon’s inconclusive word-dump, A Thousand Leaves—the first project Sonic Youth would ever record in their self-owned Lower Manhattan studio—used the freedom of unlimited recording time to vomit brawny, idiosyncratic musical matter, daring listeners to invent interpretations, but doing everything possible to make none of those interpretations true. Vocal duties for the group, up to this point, had long been split between Gordon, who played bass and sang in a detached contralto, and her then-husband Thurston Moore, who concocted strange guitar riffs and sang like a depressed alien. The badass lone-standing woman in a group full of awkward, guitar-slinging men, Gordon had also been cast into a growing litany of “modern women” in post-punk’s unfurling infrastructure—some of which cried, and some of which did not. The thing about Sonic Youth’s middle-child rock generation was that, ever so strangely, it wasn’t entirely clear which option was the correct one. And while groups like Gordon’s own resolved to throw obscurity back in the face of the market, others, like Kathleen Hanna’s hyperactive Bikini Kill or Courtney Love’s grunge-borne Hole, made their money caricaturing the extremes—neither archetype drawing any nearer than the other to an answer for the era’s defining question.

“As long as there are human beings—particularly boys and overgrown boys—around to fart, and make fart jokes, there will be cartoons.”

In 2001, a year before Sonic Youth would release their acclaimed alternative manifesto Murray Street—perhaps the closest they’d get to mastering their inconclusive neutrality—late-night Cartoon Network add-on Adult Swim began its quest to bridge a similar, long-cavernous gap between slapstick crude humor, and more mature, explicitly adult-oriented themes. Founded by mischievous funny-guy cartoonist Matt Groening, its ethos banked on oddball characters and exaggerated random-sauce appeal, a formula first toyed with in primetime TV placements (The Simpsons, Family Guy), before ultimately being banished to, and perfected in, Adult Swim’s after-dark domain. “Animated television shows and the economy of the United States have something in common—they both depend on a precious natural resource,” the New Yorker’s Nancy Franklin wrote, in a thinkpiece on the network, at its height in 2006. “But, while the oil the country relies on will run out someday, the fuel that keeps TV cartoons going, natural gas, is endlessly renewable. As long as there are human beings—particularly boys and overgrown boys—around to fart, and make fart jokes, there will be cartoons.”

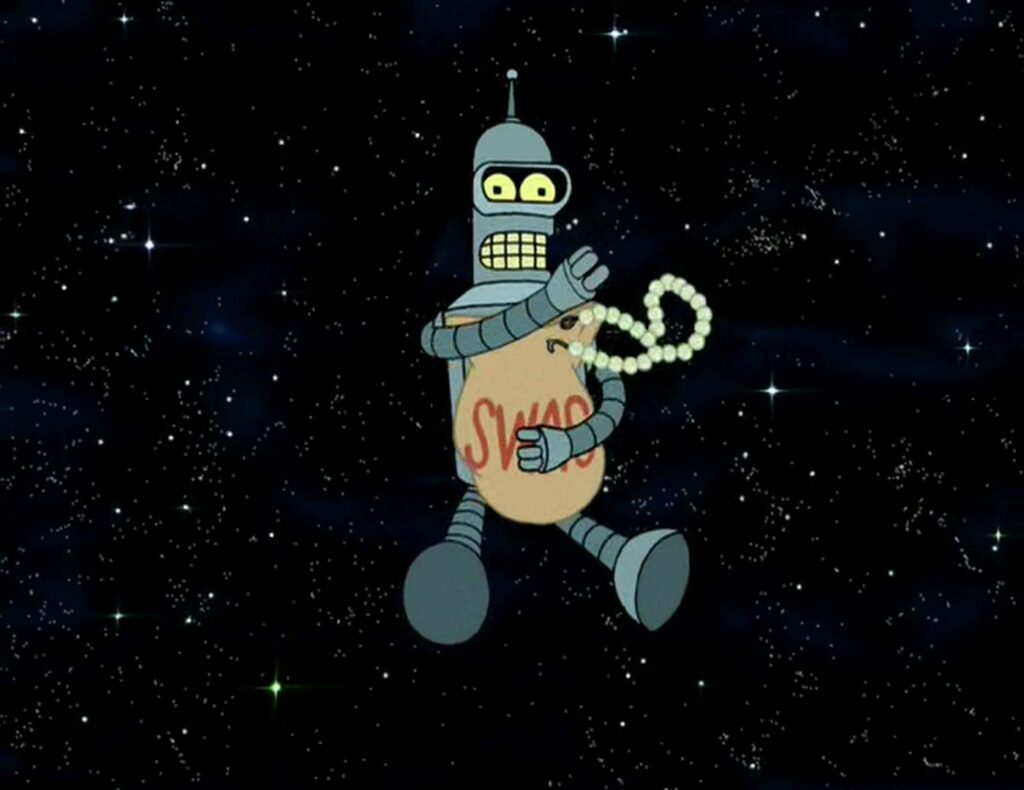

One such cartoon, marketed to fart-joke-loving boys and awkward college students alike, was Groening’s Futurama, an animated series set in the fourth millennium and revolving around the adventures of a scrappy space-dwelling delivery company. Main character Philip J. Fry (affectionately called “Fry”) is a lazy young adult who has been cryogenically preserved for 1000 years and revived on December 31, 2999; his spunky spaceship-mates are Leela, the one-eyed captain of aviation duties for their rocket home, and Bender, an alcoholic robot who speaks in angry semi-ebonics. In a weird way, when Futurama and Sonic Youth were each at their respective turn-of-the-century peaks, their dynamics banked on similar binary qualities: much like the band, the show’s structural makeup relied on the presence of (1) a group of awkward, dawdling male characters, and (2) a bad-ass female lead who was the voice of reason when inspired, or the aloof prophetess-slash-deity when jaded. There was also, just as much in the cartoon world as in the real-life one, a hefty sum of bullshit, varying in severity, to be dealt with by said female leads en route to either continued loyalty, or a decision that enough had finally been enough. In a season three episode of Futurama entitled “Future Stock,” for instance, Fry arranges for the delivery company to be taken over by a fellow cryogenically-preserved 1980s businessman—who, in turn, sells it to the oppressive monopolistic matron controlling the industry, rendering everyone bankrupt. A flustered Leela leaves along with the rest of the bunch to eat a gloomy company dinner, but is back by the next episode, assisting Fry through disastrous cooking attempts and stomach-combusting Iron Chef-inspired humiliations.

“You gotta hope even more and cover your ears and go ‘blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah!’”

The implications of continued bullshit are, perhaps, much more palpable in reality than in slapstick cartoon futurisms. After having been married to him for over two decades, Gordon divorced Moore in 2011, when he refused to put an end to a drawn-out extramarital relationship—a development that, in effect, ultimately wound up spelling the end for the band as a whole. When news of Sonic Youth’s dissolution followed the divorce’s public debut, Gordon told reporters that she would be focusing on her own work. “When you’re in a group, you’re always sharing everything. It’s protected,” she said of her post-split mentality in an Elle profile (titled “Kim Gordon Sounds Off”). “Your own ego is not there for criticism, but you also never quite feel the full power of its glory, either. A few years ago I started to feel like I owed it to myself to really focus on doing art.”

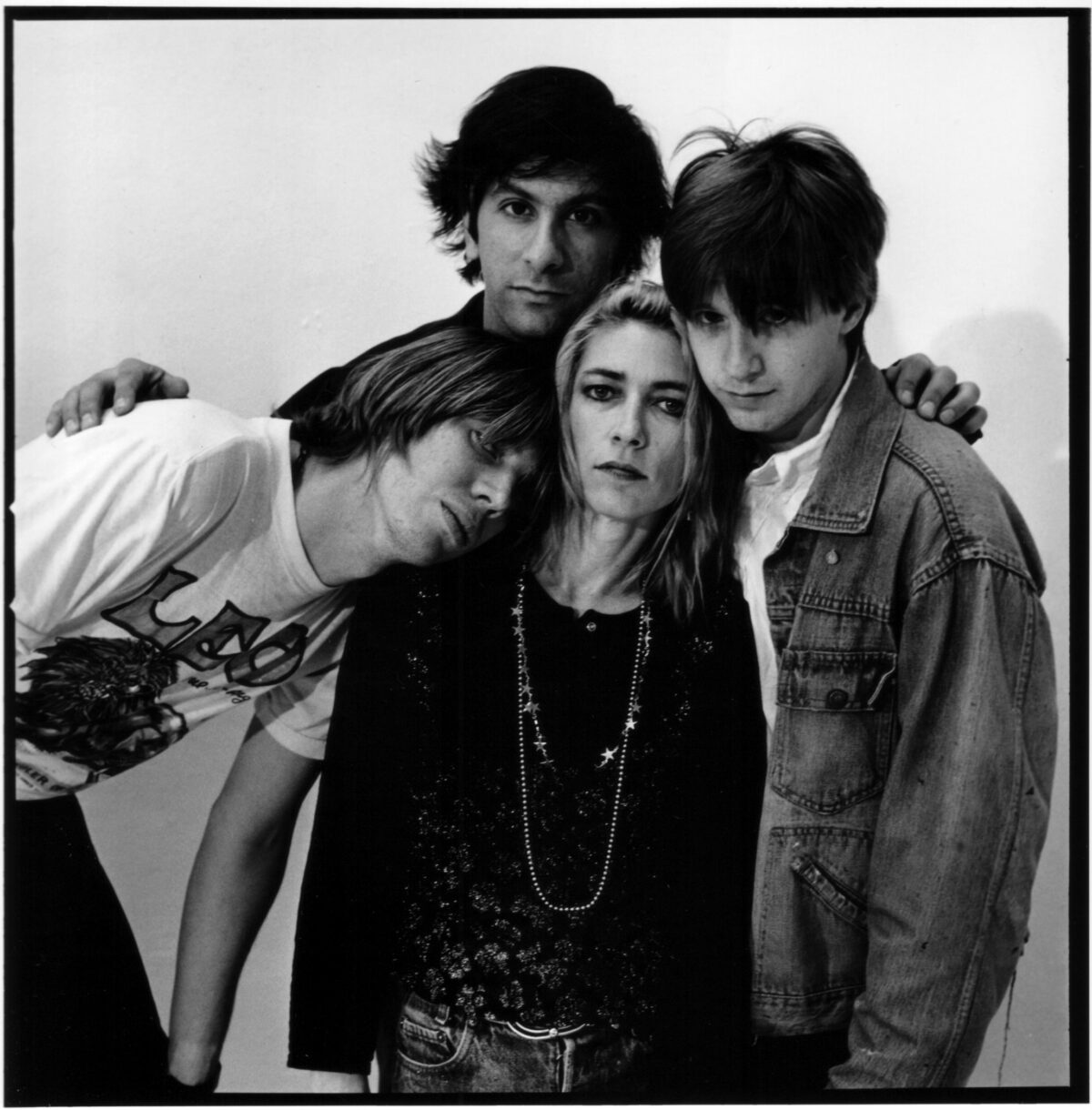

Oftentimes, though, in rock culture then—and, at some level, just as much in present-day—indulging in artistry owed to oneself also meant, for female acts, being inevitably pigeonholed into a sectioned-off category for “modern women,” while male counterparts achieved automatic canonization no matter what. For Gordon, standing alone as Sonic Youth’s sole female member, the juxtaposition between her straight-faced badassery and the group’s awkward loner ethos grew to function as a weirdly successful selling point. In live performances of “Bull In The Heather”—a track, in itself, about boredom with male-dominated systems—her vocal delivery droned with a certain annoyed stoicism, while Moore and his fellow guitar-wielding band members made funny faces, did dramatic rock-star kneels, and flailed like children on sugar rushes. Profiled alongside the group for a 1998 New York Magazine issue, Gordon described the song’s message as “using passiveness as a form of rebellion—like, I’m not going to participate in your male-dominated culture, so I’m just going to be passive.” (“10, 20, 30, 40,” she sings in its opening verse, the way you would recite a haunted nursery rhyme. “Tell me that you wanna hold me / Tell me that you wanna whore me / Tell me that you gotta show me / Tell me that you need to slowly / Tell me that you’re burning for me / Tell me that you can’t afford me.”) Interestingly, the song is constructed to sound the same way it looks on-stage: in a hodgepodge of abstract noises, her unchanging bass riff is the only steady element.

But freshly on her own, and making the art she owed herself, Gordon’s work—even when removed from the burden of a band—was severed from the canonization being in a “traditional” (see: male-dominated) act provided. Post-Sonic Youth, she delved into the world of contemporary art with a smattering of solo shows, indulging in obscure musical endeavors as side-projects. In one New York Times review of an exhibition she held in London, her artistic intuition, as was the case for many consumers, seemed to create more questions than answers: “Kim Gordon’s antiseptic show ‘Design Office: The City Is a Garden’ looks as if it were formulated by a computer bot that mixes and matches Postmodernist art clichés,” writer Ken Jonshon mused. “Ms. Gordon, better known as the charismatic frontwoman of the band Sonic Youth, intends a critique of high-end real estate development in New York City, but what she has wrought is unimaginative, conceptually facile and oddly impersonal.” Strangely enough, a very similar argument can be wielded—especially in the case of acclaimed-yet-obscure records like the aforementioned A Thousand Leaves—against Sonic Youth’s discography, which, unlike Gordon’s work as a solo artist, lived instead to see its ambiguity subjected to widespread deification. Why is mix-matched directionlessness ahead of its time in one sphere, one might ask, and unimaginative in the other?

In a season three episode of Futurama entitled “Godfellas,” Bender is irrecoverably launched into the universe after being accidentally ejected by a torpedo tube midway through an attack by space pirates. (I am aware of the craziness and unreadability of the previous sentence.) Desperate and running out of options, Fry, being the unwise dawdling young adult he is, opts to visit a far-away group of monks who use the world’s most powerful telescope to search for God. (We soon learn that the monks have been searching for 700 years.) In an odd shop called Ed’s Hiking Supplies & Spelunketeria, Leela engages him in a much-needed discussion about just how impractical the move they’re set to make—the frantic purchase of a mule and a sherpa to lead them down a winding path to the monks’ lair in the Himalayas, no plan in place for when their odd request to use the sacred God-searching telescope is inevitably rejected—may actually be. “You can’t give up hope just because it’s hopeless,” Fry says, as the shop owner fetches a fully-equipped mule from a high up on a shelf. “You gotta hope even more and cover your ears and go ‘blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah!’”

Much like the weird-cool-guy rhetoric of Sonic Youth, the hope of the main character is often as impractical as it is marketable—and at some point, as Leela ultimately does in the episode, the voice of reason always seems to be tasked with sacrificing practicality for the majority’s fever dream.

🛰️🛰️🛰️

“Is there really a mainstream and an alternative, or is it all the same thing in different outfits?”

The opening portion of Kim Gordon’s 2015 autobiography Girl in a Band is titled “The End,” and presents a sobering retrospective on Sonic Youth’s final concert. “Onstage for our last show, the night was all about the boys,” she writes, as stonily as she sings. “(…) Thurston double-slapped our bass guitarist Mark Ibold on the shoulder and loped across the stage, followed by Lee Ranaldo, our guitarist, and then Steve Shelley, our drummer. I found that gesture so phony, so childish, such a fantasy. Thurston has many acquaintances, but with the few male friends he had he never spoke of anything personal, and he’s never been the shoulder-slapping type. It was a gesture that called out, I’m back. I’m free. I’m solo.”

Sonic Youth’s appeal hinged heavily, for as long as was possible, on the sale of a dream for eternal childhood—perfectly fitting, like Groening’s Adult Swim utopia, for a post-adolescence crowd reluctantly coming to terms with looming grownness. Moore’s lanky awkward quality was of the endearing, Joey Ramone category, until it transitioned from young and angsty, to old and contrived. Much of the band’s popular work dwelled on the anxieties of growing up in a crazy world—in the welcome-to-my-crazy-dystopian-life lyricism of a track like 1988’s “Hyperstation,” Moore narrates his way through sloppy apartments, 3 AM beatdowns by kids in basketball attire, and sick days borne from destroyed amplifiers—but by 2009, when their fifteenth and final LP The Eternal first appeared in stores, decades of aging seemed to have no effect on their coming-of-age positionality. “Don’t you love me yet?” Gordon shouts to an unnamed interest in the LP’s opening track. “Press (me) up against the amp / Turn up the treble, don’t forget.” As much as it hurts to admit, it sounds a lot less sexy when high-testosterone romance trips may very well start in hotel beds and end in hospital ones.

“Free time, free time… Did I mention that you control me?”

The Eternal represented just as much of a return for Sonic Youth as a goodbye—its three-year recording process just so happened to make it the longest-awaited album in the group’s history—and in the same late-aughts cultural growing-up stage that saw the band come and go, Futurama sought to put together a dubious resurrection moment of its own. In 2007, when Adult Swim ceased airing its reruns, the show was picked up by Comedy Central, where a dozen or so previously-unaired episodes (solely available, up to then, via the purchase of a for-sale box set) were released with the permission of 20th Century Fox. Two years later, the channel extended the show for 26 new episodes, stretching it out to a sixth and seventh season aired from 2012-2013. As of the writing of this piece, a 2023 Futurama Hulu reboot is in the works, but—as was the case for its several previous raisings from the dead—there remains, still, a question to be asked about how relevant its own messaging, and that of Adult Swim at-large, really is in an era that has every reason to have graduated from it. In a 2019 Guardian article that begged the question of how Futurama “went from sci-fi to sci-why,” writer Ben Gazur argued that the show had simply run its course, and did not let go when it needed to. “Many of the old writers had moved on to bigger things,” he noted of the period between its cancellation and Comedy Central revival, “and instead of leaving a perfect legacy of genius comedy, the show decided to try new things. Like being stupid. And unfunny.” Unlike the real-life Kim Gordon, in Leela’s cartoon world, there was no option on a sinking ship—not divorce, nor dissolution—but to sink along with it.

Gordon’s fellow punk rock “modern women,” despite not being bound to cartoon galaxies, faced a similar ultimatum: either live and die according to the whims of post-punk’s opaque ethos, or create a brand for oneself, even if it ultimately meant sacrificing placement in a wider canon. The unlikely star of “Bull in the Heather”’s music video is Kathleen Hanna, the all-out energetic Bikini Kill frontwoman rumored to have once been punched in the face by Courtney Love. In the clip, she plays the role of a borderline-deranged pest, throwing herself onto stoic band members as they struggle to simultaneously push her away and play their instruments. Interestingly, decades removed from the wild ethos exaggerated by her cameo—one where she was overwhelmingly loud, and Sonic Youth came across as the voice of reason—the band, living epitomes of the post-punk ethos they championed, now seems to have shrunken back into banality, while its symbolic annoying little sister does the future-focused thinking its audiences once sought in its music. “Is there really a mainstream and an alternative, or is it all the same thing in different outfits?” Hanna wondered aloud, in a 2019 Q&A with Pitchfork’s Jenn Pelly. The interview came with news of Bikini Kill’s reunion, and spanned Hanna’s journey from fiery provocateur to introspective feminist voice. “Also: What are the feminist projects? Are they working? Who are they for? Who do they benefit? What role does criticism play in art-making? And, do I have to adopt new rules to enact my politics? How important is the subjective voice?”

Questions are inherent to any agent that seeks to fill a cultural void—whether an awkward New York City No Wave band or a slapstick futurist Adult Swim show—but the distinguishing factor in telling said agents apart, it seems, is whether they deem those questions worthy of an answer. Sonic Youth spent their active days being vocal advocates for impenetrable “art rock”; Matt Groening, beyond just Futurama, often seemed to be making shows more for the sake of fart-joke humor than concrete adult lesson-bestowment. “The jokes arrive with the same profuse variety and impressive deep geekery that Groening has trained a spoiled audience to expect since the début of ‘The Simpsons,’” the New Yorker’s Troy Patterson wrote in a 2018 review of his then-new Netflix series Disenchantment. “Anachronistic puns, ye olde sight gags, poised ripostes, and throwaway lines ranging from subtle references to art history to blunt-force allusions to heavy-metal bands.” Though any sitcom, animated or not, needs some kind of moral takeaway per episode in order to remain on air, a canonical glimpse at Groening’s cartoon empire—from Futurama, to the Simpsons, to Disenchantment—poses a necessary, still-unanswered question about whether the point of TV can simply be to watch it. And much like the control he once boasted over America’s young-adult minds, the matter is entirely out of his hands.

“Something that looks overtly political might just be a design, and what looks like a design might be political.”

Sporadically interspersed throughout “French Tickler,” the sixth track on A Thousand Leaves, are directionless musings by Gordon about free time. “Free time, free time / I have got it gonna get me some / Free time, free time / I would spend it forever captivated,” she drones drily, in the track’s opening verse. By the time the guitars fade out, the free time seems to have won. “Free time, free time… Did I mention that you control me?”

As impenetrable as Sonic Youth intentionally made themselves on the record, Gordon’s drawl is one of few places where American listeners might have found something that resembled themselves. The climate that produced Adult Swim and A Thousand Leaves was one rife with desperation for some form of escape—whether it be from turn-of-the-century politics, turn-of-the-century capitalism, or some other nationwide turn-of-the-century growing pain—which led people to the most extreme cultural crevices, all in search of the same elusive, precious asset she serenaded. But if time is money, free time is free money, and neither of those things exist. What point is there, Kim Gordon often seemed to ask, in pretending they do?

The trouble is that reality isn’t marketable—and what isn’t marketable doesn’t make money, which means, at least in America, you die. The job of the artist, and the job of the “modern woman,” both in Sonic Youth’s heyday and in the confused debris it left, remains just as much a mirror to the system as it was before. “I don’t see the artist’s role now as any different now than a year ago—to hold something up as a reflection,” Gordon told the New Yorker’s Amanda Petrusich in a 2020 Q&A. “But maybe how a person gets to the point of making art is different now. What was considered a closed system might have become more open. I always think of my art as political, in that it’s social. But there’s no single way to make art, or to be political. Something that looks overtly political might just be a design, and what looks like a design might be political.”

To be both design and political—a tightrope Sonic Youth and Futurama each stumbled along before ultimately falling off—might just be as asymptotic as free time. And for as long as that remains true, even in future millenniums boasting cryogenic preservation techniques, free money in America will always be as funny as fart jokes.