A strange experimental novella meets a city-bred hard rock tradition.

SAMUEL HYLAND

Two winters ago, the anti-disciplinary artists Jason Hirata and Tony Chrenka joined forces to present Plot, a mixed-media exhibition packed neatly into a derelict basement gallery near Chinatown. One day that December, I took a set of connecting subway rides to the space’s Lower East Side stomping grounds, where ritzy big-city romanticism segues off into loud impasses and louder weed. During summers, the breath of New York seems to change around Canal Street—a collaborative stench, shared between sleep-deprived vendors proffering counterfeit Balmain, coffee-mouthed fashion types on urgent calls with unpaid interns, cab drivers peddling profanities through windows, and lonely smokers lurking in the doorways of fast-food chains. Subway stations sweat mysterious liquid onto unsuspecting heads; the garbage trucks sound as if they’re groaning, every block a violation of their elderly bodies. Stinkier and stuffier, the city’s air is a sentient wall closing in—smushing all victims, man or machine, into territory where all things must be felt at all times.

When Plot opened its doors to the Lower East Side’s art-world underground, New York City, like any other hell, had frozen over. A once-bustling pedestrian population was zombified, in part, because of an aggressive new COVID strain swiftly making its rounds. But in a way, as is integral to Manhattan winters, it also felt as if the conveyor belt beneath summertime’s all-feeling machine had halted, violently chucking its inhabitants—fashion types, counterfeit Balmain vendors, profane cab drivers, doorway smokers—back into the doors from which they emerged. At the derelict basement gallery near Chinatown, those doors led into a well-lit mini-expanse of strangely contorted objects and detailed pencil drawings. I was told by a gallery assistant that for Hirata’s portion of the exhibition, he’d ordered construction ephemera on eBay, flattening his hauls to conjure jarring visual arguments. Down the space’s bright-white hallways, sketches of ghastly gatherings sat within feet of decimated ladders and storage shelves. One of the ladders was titled Different Way of Telling the Same Story, and in some sense, New York City’s own tale—of crushing, contortion, and loose assemblages—couldn’t help but ring eerily true.

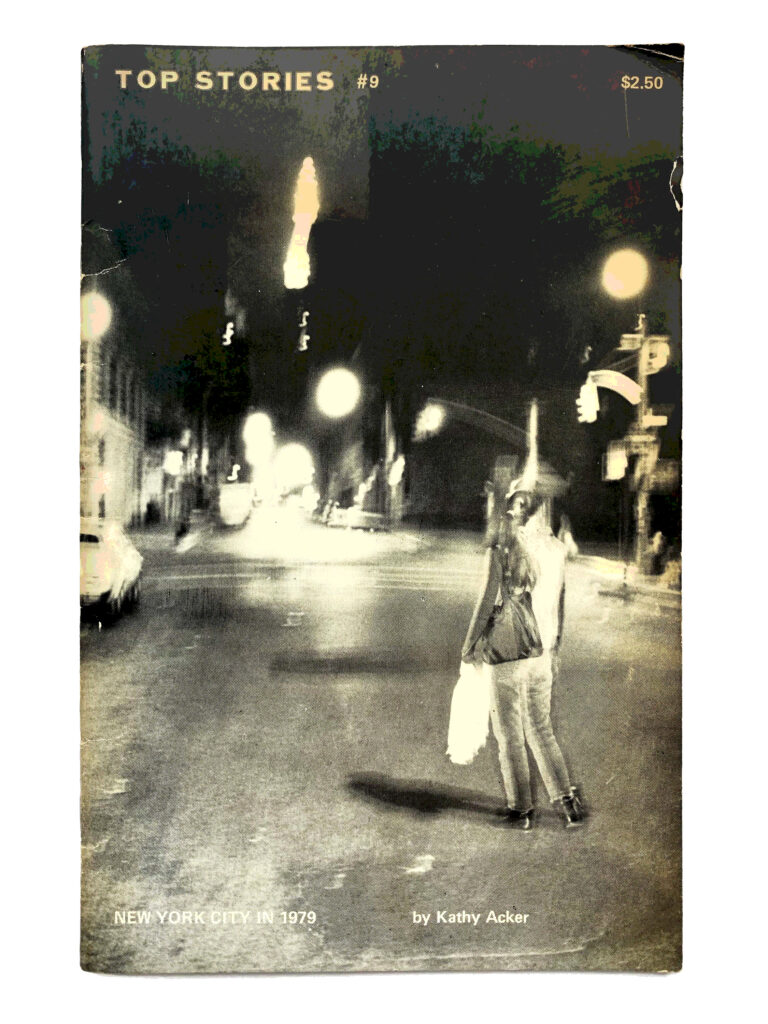

New York City in 1979, an experimental mini-novel by the cult literary genius Kathy Acker, takes place in a universe familiar to Plot’s: one where you either crush yourself, or allow the city’s sentient air to crush you. A terse tagline christens the project, in oft-recycled words, as a “tale of art, sex, blood, junkies and whores in New York City’s underground.” On the front cover of its first edition—reduced to a photocopied page in the cheaper Penguin Modern reprint I own, because I splurged on Depop and couldn’t shell out $137.57 for a used original version—there’s a blurry photograph of a lone woman traversing the city’s dusky roads, sort of like PJ Harvey on the cover of The Mess We’re In, but a little more ominous. Within ten of its forty-five pages, “Johnny,” a hazy recurring character of ambiguous sexuality, is vignetted between descriptions of oppressive weather and equally-oppressive delinquency. “It’s four o’clock A.M,” Acker writes, midway through a half-sell of his odd persona. “It’s still too hot. Wet heat’s squeezing this city. The air’s mist. The liquid’s that seeping out of human flesh pores is gonna harden into a smooth shiny shell so we’re going to become reptiles.”

“Don’t fucking make excuses, just do what you know how to do and don’t fucking make excuses, just do it.”

Much of New York City in 1979 comprises similar half-ideas, strung together by fleeting narratives and aggressively-graphic eroticism. Its premise is a loose locus of distant, almost disembodied voices—vaguely akin to Chrenka’s indistinct assemblages, stuck somewhere between roughly endearing and threateningly occultic. (One sketch of his, fittingly titled Untitled (Group), featured a circle of smushed-together silhouettes, a few of them inexplicably colored in.) Oddly enough, of all the canonized New York City literature that exists, this puny avant garde art-book feels far more authentic in its unresolved imprecision. Its titular city is a breeding ground for haphazard intersections, a long-neglected nest of knotted wires no man, nor author, may ever detangle, let alone debug. Like Plot, there is no “plot” to the city’s coexistence-by-force but decimation and its confusing debris. The only way to document the city, perhaps, is to tape-record its voice the way Acker does: less full sentences, more groaning garbage trucks; less clean-cut resolutions, more murky impasses; less catharsis, more violent, drugged-out desperation. “It’s amazing,” a teenager told a journalist in 1996, upon seeing Acker recite her work live. “She comes out with just the toughest, craziest stuff. But somehow she makes it sound lyrical.”

Around the same time that Acker garnered acclaim as a “punk” writer, her hometown musical scene began to experiment with similar tape-recordings of New York’s ugly death rattle. “No Wave,” an inventive movement fronted by provocateurs like Sonic Youth and DNA, drew less inspiration from packaged sounds than experienced ones—taking construction tools to guitars as homage to street clamor, or exchanging Zildjians for scrap metal in service to shady alleyways and their night-long clankings. As much as the scene’s initial iteration died an abrupt death—fittingly, depending on who you ask, at the hands of an attempt to document it—its detritus remained a loose guide for young acts taking on the same terrain, newly tasked with translating its filthy groan. Six years ago, the New York City hardcore outfit Show Me The Body released Corpus I, a self-proclaimed “collaborative mixtape” that melded moshable quasi-metal with the quirks of an eclectic, genre-spanning guest list. Sprawling across nooks and crannies of New York’s intersecting sonic enclaves, it featured characters including the soul singer Mal Devisa, the hip-hop producer Tony Seltzer, the wunderkind-slash-enfant-terrible Princess Nokia, and the electronic composer Eartheater. About halfway through the record, a track called “Stress” saw Cities Aviv, the punk-rock frontman turned hypnagogic rap emcee, weaponize his bestial growl against New York’s pressure-makes-diamonds conveyor belt. “Tension… breeds… perfection,” he belted, like a vein-popping father reprimanding children between spankings. “Stress, stress, stress / no leisure.”

“I fucking hate my reality. That’s why I turn on the TV.”

As is true for New York City in 1979, the record’s clearest captures of Manhattan came in the moments where its voice was disembodied, less attributed to a single person than a ubiquitous idea. Corpus I is peppered with monologue-style interludes voiced by anonymous figures; on the album’s 7-second-long opener, a heavily-accented entity sneered a tirade that may well have come from the city’s own mouth. “I don’t give a fuck what you do, just do whatever,” the voice demanded. “Don’t fucking make excuses, just do what you know how to do and don’t fucking make excuses, just do it.” New York runs on a flesh-eating treadmill, and in a way, its willing hamsters—man and machine alike—have no conception of stopping, let alone for long enough to realize that they are being decimated. Stuck to the wall of a derelict Chinatown basement gallery, Hirata’s flattened ladder probably thought it still worked. New York City is a fancy showroom for about eight million mangled ladders just like it: a sanctuary by definition and a sacred one by ethos, just grand enough in premise to make its downfalls worth dying for. “Tomorrow we’re back on the street again,” one of two jailed sex workers, the other heavily bleeding, declares within three pages of Acker’s novel. “If we’re lucky.”

Where said “luck” might exist in New York City in 1979’s universe, it’s telling that melancholic suffering is often sprawled out, like a corpse, in its place. I’m reminded of Taxi Driver, the classic Martin Scorsese film in which a misanthropic Robert De Niro follows his heart into a bloody, all-out shooting spree. In an early blip of role solidification, his character—freshly in love with a campaign worker, and hoping to bring her further into his world—invites his romantic interest to a pornographic film screening, languid throughout, and devastated when she splits on bad terms. Scorsese’s New York, like the New York of Kathy Acker and Show Me The Body, hinges less on direct hits than deathly miscommunications. And such miscommunications, when translated into transgressive art, often come across as more blatantly offensive than their real-life analogs. “I don’t turn on the TV to see my reality,” a friend recently told me. “I fucking hate my reality. That’s why I turn on the TV.” If gritty, atonal city-bred rock music is a twisted iteration of reality television, it’s worth looking at Sonic Youth & company as funhouse mirrors, a warped image of our tense collective dynamic. Sometimes, especially in their earliest records, it sounded like their instruments were bickering with one another, or full-on fist-fighting—much to the pleasure of fringe realists, and the chagrin of about eight million broken ladders, hellbent on not being reminded of their brokenness.

On “Just A Slither,” perhaps the most somber song on Corpus I, the retro-futuristic singer Negashi Armada strains his low-tenor voice along a walk-up bassline, vaguely reminiscent of Kanye West’s “Late.” “Does anyone know my great great grandmother’s name?” he asks, the way an orphaned child might on a Broadway stage. “Does anyone know from where I came?” No one does, and no one ever will, because New York City—in 1979, 2017, and 2023—is equally hardwired for generation and destruction. Choose to be reborn in its bowels, and it will shit you out, a great-grandmother-less ladder with new existential questions you may answer in one of three ways: art, work, or death.

💉💉💉

“A grave is spreading its legs and BEGGING FOR LOVE.”

New York City in 1979 is split into a number of fragmented vignettes, not necessarily chapters, but not really sub-sections, either. The second of these mini-narratives closes with a critique that feels, years later, like both a contrived dystopia and a precocious prophecy. “Since the United States government, having decided that New York City is no longer part of the United States of America, is dumping all the laws the rich people want such as anti-rent-control laws and all the people they don’t want (artists, poor minorities, and the media in general) on the city and refusing the city Federal funds, the American bourgeoisie has left,” Acker writes, as if squinting at the grinning face of Eric Adams through a foggy crystal ball. “Only the poor: artists, Puerto Ricans who can’t afford to move… and rich Europeans who fleeing the terrorists don’t give a shit about New York… inhabit this city.”

In the pandemic-informed context of Plot’s opening, discourse around New York’s population fell along eerily similar fault lines. Among those rich enough to escape, when conditions worsened, were familiar culprits: politicians, influencers, transplants from elsewhere. Doomed to suffer, on the other hand, were the less-affluent residents who remained—always remained—when the American bourgeoisie had fled towards either vacation homes, or less-trendy (and therefore more safe) states of origin. Perhaps the most accurate tape-recording of New York City, aside from experimental gothic literature and aggro no wave, is the dividing line between those who can only ever speak highly of it, and those who have witnessed its hideous underbelly without means of escape. The only correct relationship to have with it, when it has revealed itself, is love-hate, if not hate alone.

Show Me The Body is more hardcore than no wave, which means that their hatred is more a matter of producing uncomfortable noises than emulating them. As of the writing of this piece, the band’s most recent album is 2022’s Trouble The Water, out via their longtime label Loma Vista Recordings. Among the most frenetic moments on that project is “Buck 50,” a feedback-heavy tale narrated by a violent city slicker. “Box cutter in both socks, it’s stashed,” frontman Julian Cashwan Pratt snarls, the instruments whirling into a thumping frenzy. “Buck 50 your ass / no love in the heart of the city, I laugh.” Especially on this album, Show Me The Body’s music is often carried, strangely, by its lack of loud bass guitar: a subtle directionlessness that, when paired with overblown amps and primal howls, feels ever-so-slightly like you’re walking alongside them on life-or-death adventures, no rulebook available besides crude, morbid intuition. To Acker’s characters, all of whom seem to be following the same broken compass (moral, too), life-or-death appears the only dichotomy present, its urgency seeping into everything from inane exploits to lofty philosophies. “New York City will become alive again when the people begin to speak to each other again not information but real emotion,” an unnamed female narrator declares at one point, nerviness palpable in her stream-of-consciousness prose. “A grave is spreading its legs and BEGGING FOR LOVE.”

“When they grow old and their skin rots and their bodies turn to putrefying sand and they can’t do physical exercise and they can’t indulge in bodily pleasure and they’re all ugly anyway; suddenly they got nothing.”

Love figured deeply into Acker’s literary identity, and perhaps it’s a perspective garnered only from surviving a city that actively hates you. In 1983, around the height of her folk infamy, she was interviewed by an NME journalist who asked her what the deal was with all the sex in her writing. “I don’t actually think there is so much sex but at least I’m getting less flak for it now than I used to,” she offered. “I think it had to do originally with people finding out I’d done sex films to support myself when I was buying time to write. I realised early on I was going to have to prostitute something and I was damned if it was going to be my mind. I just did a few films because I could live for a long time off the money.” If you remember “Johnny” from earlier, it’s interesting to note that early on in New York City in 1979, he goes on a similarly-rooted tangent, midway through trying to seduce Janey, his eventual sex partner:

Wouldn’t you like to give up this artistic life which you know isn’t rewarding cause artists now have their work/selves into marketable objects/fluctuating mages/fashion have to competitively knife each other in the back because we’re not people, can’t treat each other like people, no feelings, loneliness comes from the world of rationality, robots, every thing one as objects defined separate from each other? The whole impetus for art in the first place is gone bye-bye? You know you want to get away from this media world.

Maybe what makes Acker’s premises, and the escapist urges of her characters—even when these characters are too hazy to be relatable—so vivid, is that they’re escaping from things that will never really stop demanding escape. The “impetus for art,” decades later, remains in constant flux, perennially determined by what exactly its upholders are fleeing from. As of right now, among those predators are versions of the “robots” Johnny references: a litany of A.I technologies, inspirational to the workaround-seeking overworked, and terrifying to English professors intent on seeing forms for all their complex parts. It’s a dilemma similar to the one addressed by No Wave, a foundational root of Show Me The Body’s no-holds-barred ear towards Hell’s disembodied groan. Given the option to either work around ugly realities, or amplify their ugliness, the city’s most inventive acts opted to reclaim hideous truths, churning them into something alien and uncomfortable. New York City in 1979, though technically a text of many literary definitions—art book, novella, experimental poetry collection—is also a quintessential Manhattan punk rock album, more infatuated with gritty underground fables than bubblegum stories from the surface.

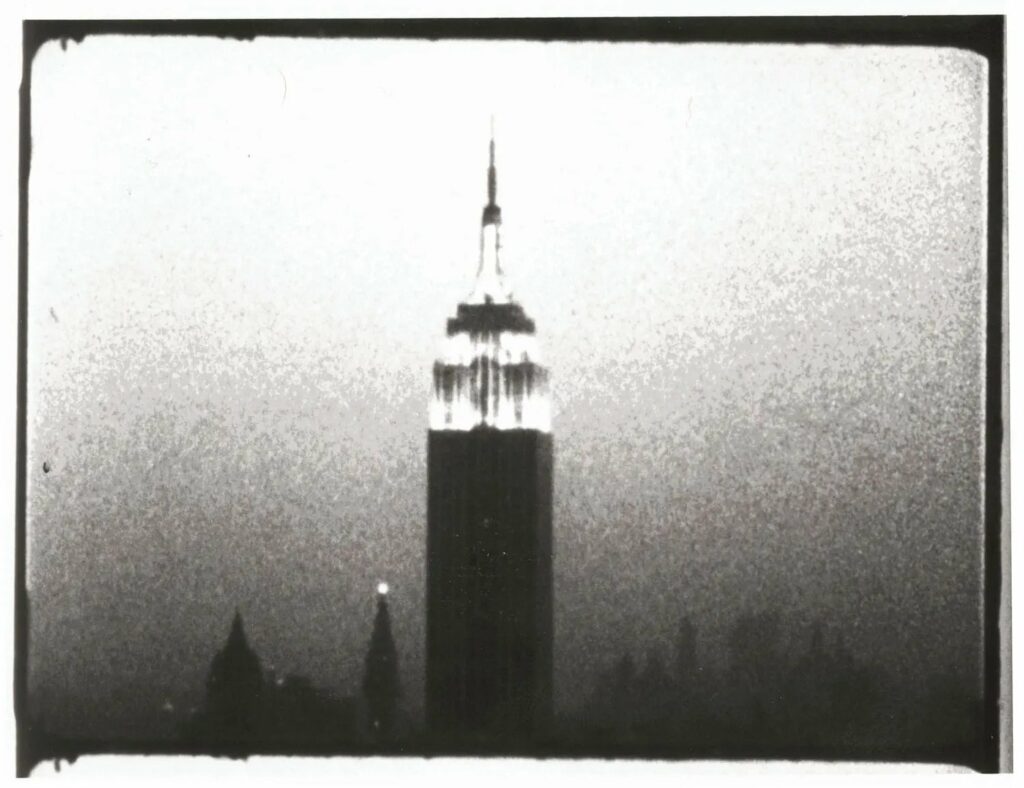

On a national scale, in the years preceding Acker’s rise to New York myth, tensions between surface and sewer played out in an East-West cold war, waged between a San Francisco hippie movement and a Manhattan-bred proclivity for grimmer aesthetics. While marijuana-nirvana evangelists like The Grateful Dead ravaged Californians with preachings of peace and escapism, Andy Warhol’s Velvet Underground latched gripping music to not-so-escapable verities, ambling through quotidian sacrilege as if all people might find it relatable. “I don’t know just where I’m going,” abrasive frontman Lou Reed sang in “Heroin,” a love letter to its titular substance—all-but-currency in the New York Hell he, and his band, called home. “But I’m gonna try for the kingdom, if I can / ‘Cause it makes me feel like I’m a man / When I put a spike into my vein / And I’ll tell ya, things aren’t quite the same.” The art of New York City, in the late 1960s, was often similarly directionless, masturbatory and self-referential: a visual language inextricable from Warhol’s obsessive practice, which hinged on relentless documentation, even if it meant nothing at face value. Among several Warhol artworks preserved in the National Library of Congress is Empire, an 8-hour silent film depicting the Empire State Building throughout various stages of a day. Much like New York City in 1979, the unsuspecting project is, oddly enough, one of the most retrospectively accurate images of its stomping grounds. Its plot is that there is no plot; time passes, and while you die, the city, your killer, lives to see the sunrise.

“Since most people spend their lives mentally dwelling on the material, they have no mental freedom.”

New York City in 1979’s penultimate chapter is titled “Intense Sexual Desire is the Greatest Thing in the World.” The mantra is given a standalone spotlight on the first page of my Penguin Modern reprint, a gesture that invites lofty thematic interpretations. Intercourse is only had once in the novella, while the vast remainder of it traipses along various flirtations—fitting for a city that generates perpetual longing, but only ever simulates “having” with more wanting. Late in that chapter, Acker devotes a scathing set of paragraphs to critiquing the elderly. “Since most people spend their lives mentally dwelling on the material, they have no mental freedom,” she writes. “When they grow old and their skin rots and their bodies turn to putrefying sand and they can’t do physical exercise and they can’t indulge in bodily pleasure and they’re all ugly anyway; suddenly they got nothing.” Aging, in Acker’s world, is the physical marker of decimation: a set of wrinkles on once-smooth skin, the same way Hirata’s ladders were ridden with bends and dents, damning blemishes on what was once stainless steel. Time obviously ages us more than any city ever could, but in some cities, the process is more relentless. When time collapses into itself, and the wires of New York’s crimson machine tighten around coffee-soaked necks, the very things we spent lifetimes chasing are revealed to be fleeting. “At the door to Janey’s apartment Johnny’s telling Janey he’s going to call her,” Acker writes in the book’s final lines, following a consummation of the plot-long sexual tension. “Johnny walks out the door and doesn’t see Janey again.”