AINT WET IS ON SOME REAL NYC SHIT.

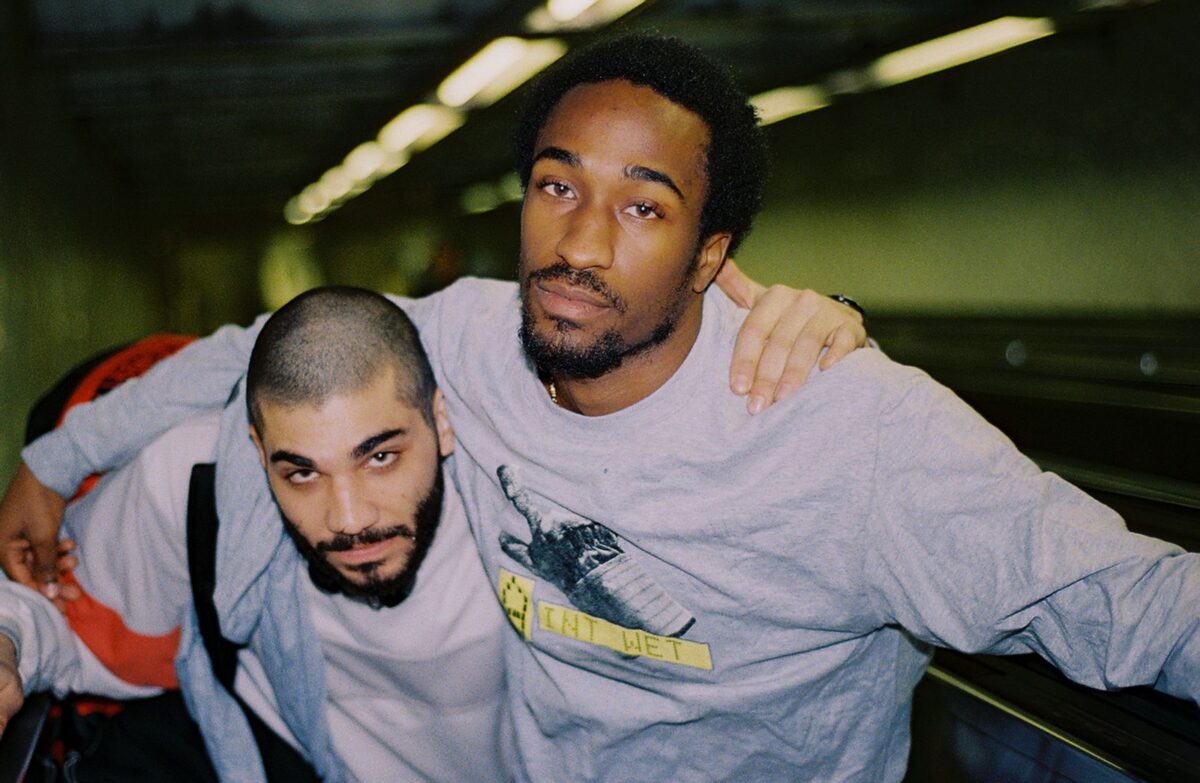

Assorted throughout the article are behind-the-scenes photos from a MIKE music video shoot. ABOVE (left to right): AINT WET co-founder Abraham “Abe” Mohamed El Makawy and Nate Cox at 181st Street.

SAMUEL HYLAND

It’s a few hours past sunrise on a muggy August morning, and – though slightly groggy – AINT WET co-founder Abraham El Makawy is cozied up in his apartment sporting a beige crew-neck and a pair of constantly moving eyes to go alongside it. Any grogginess is understandable. Just a few hours earlier at 5 AM, he was at the Brooklyn Heights Promenade for a music video shoot with his longtime friend and collaborator MIKE, a potent new-generation hip-hop talent, and Naavin Karimbux, Mike’s manager and Abe’s roommate. “Like I said, I’m a bit delirious because of that 5AM shoot,” he tells me, easing back into his chair after a charger-run-turned-gallery-tour. “But it’s cool. I think you’re going to get a more, like, cerebral version of me, which will be funny.”

AINT WET emerged from the rubble of Hurricane Sandy in 2012 at the hands of Abe and his best friend Mikey Saunders. In the beginning, the two collaborated on prints in the former’s family-owned shop as a hobby; but, with time, a difference in life paths threatened to break up the function: Abe was on the artistic side of things – Mikey was going to college for computer science (I shouldn’t leave out that Mikey was interviewing for a job at Google during our chat). The company was, for the most part, an answer to the daunting question of whether this connection would have to end — “an opportunity to keep on doing something together,” El Makawy says — and, since then, one of few authentic lenses into the inner-city culture of New York, boasting an unapologetic level of intimacy lazily emulated by hordes of others past and present. The City is an omnipresent facet of the AINT WET vision. Their website is coded to resemble the kiosks found in its widespread MTA subway stations; the line of tube socks they dropped a year back is specifically tailored to resemble the tiles found in Brooklyn’s Carroll Street station; much like Midtown’s on-the-street salespeople, they sell Welch’s fruit snacks on their online page for a dollar (the original idea was loosie cigarettes, but, Abe told me, throw an underage visitor into the equation, and that becomes bad for business).

Most artists pride themselves on the idea of moving up in the ranks. They hastily publicize landing reputable clients, being commissioned for widely known projects featuring widely known figures, being recognized on a larger scale in any way, shape, or form. For AINT WET, virtually the opposite: most dignity lies in genuine connections forged naturally over time. With MIKE for example, a foundational friendship was established long before any musical face of AINT WET was put in place. “I’ve known Mike prior to this,” Abe tells me, “this” being the aforementioned 5 AM music video shoot in support of Mike’s latest album Weight of the World. In conversation, Abe refers to the figures he’s fostered similar relationships with – most of them celebrities from the onlooker’s perspective – on a first-name basis: Earl Sweatshirt as Thebe, King Krule as Archy, Matter Research (the label that covers UK-based acts like Jadasea) as simply Malcolm, it’s creative mastermind. And – even with such an impressive list of collaborators as this – he is considerably less trigger-happy about publicizing the content he creates alongside them. “With Thebe, it’s the same thing,” he tells me, following a reflection on what it’s been like watching King Krule grow into a father. “I’ve known him for several years as well, and you know, there’s like – I helped on Some Rap Songs visually, a little bit, but not to where I would post on IG. It doesn’t matter, because you’re just helping out a friend with a piece of something; they’re calling in a couple ears, a couple eyes, to look at something.” He imitates the concept of levels by bringing his hands closely parallel to one another, all fingers fully extended, then raising one down-facing palm slightly above its counterpart. “It doesn’t really work like this – like a ladder – where it’s like “AINT WET’s gonna do some shit with Jay-Z” – I mean, that would be lit, but it’s almost just how the world unturns. (. . .) We all come to each other for advice.”

Abe’s immediate network consists of musicians, journalists, label reps, and various other characters neck-deep in artistic and creative industries. It’s a web of connections that consistently offers mutual support predicated upon each individual’s thing, whether it takes form in Jeff Ihaza profiling AINT WET for the FADER back in 2018, or Abe designing artwork for several of MIKE’s albums, singles, and tours (one promotional poster for Mike’s Sidewalk Soldier tour [carved into a sidewalk tile] was a highlight of the impromptu house tour Abe took me on while fetching his phone charger).

“You can’t just say you don’t fuck with art.”

Two days ago, transporting to and fro for a kitchen paint job needed by a friend, Abe got to ride the subway for the first time in months. In the time spanning the initial New York City lockdown and now, he tells me, he has found some space to focus on himself – “to be Abraham.” Normalcy has been redefined; The conjoined relationship between AINT WET and the city has been physically inhibited.

Yet – on this morning – he was able to ride the subway with longtime friend Elijah Maura. The two hung out at Los Hermanos, a traditional South American taqueria they frequented exclusively pre-COVID. They traversed the boroughs through railroad tracks, taking the L from Williamsburg, the Q from Manhattan, a number of other lines so vast that it proved difficult for Abe to recall.

And – somewhere within it all – they got off at one station, took out their stuff, and plastered a sign onto the nearest subway pole.

“AINT WET,” the sign read.

THE AINT WET INTERVIEW

SAMUEL HYLAND: MIKE is one example of an artist you go way back with. I was reading this piece that went out about you in the FADER in 2018, and it was talking about how you guys usually work with people in close quarters. How have those relationships with, for example, MIKE, persisted over time since you started out?

AINT WET: I think that when you’re an independent designer, or a person that isn’t working for a company, you really depend on working with a network, like you mentioned. The disconnect between business and friendship – those lines blur. I live with MIKE’s manager, who was a work friend before he was a homie; we became friends through the shit that we were doing for work. So with MIKE there’s an element of that that’s certainly true, but like – I’ve seen Mike grow up. I’ve known him since he was eighteen years old, maybe younger, maybe he was like 17 / 17 and a half. So, like, that’s like my little brother. And that’s not to say – I mean, spiritually, the man’s like a hundred years older than most people I know – but simply on a life shit level, I’ve seen him really transform. So that’s beautiful. And you have to be a little more understanding; there were definitely times over the years when a disconnect from like “Oh, you’re just like five years younger than me,” you know, you’ve just got to be a little more sensitive – But at the same time I think that makes something really pure. Me and Mike have sort of a symbiotic creative relationship. There are things that are direct and there are things that are just incredibly intuitive, where I just kind of know where his head’s at, or he just trusts me – and that’s not something you just get from working with somebody off the bat. That’s something that comes with family, and community, and spending so much time with someone.

SH: Just to set the table, how did you guys get started out?

AINT WET: I mean, there’s so many different angles to an origin story – do you wanna like, maybe to diversify the question, ask me in a more specific way?

SH: Sure. In the follow-up to this question, I was going to ask about the name itself, which, in the FADER piece, is said to have sort of a double meaning. The first meaning, of course, is the subway poles, and then the next one is Hurricane Sandy, which you guys survived. So about the name, that angle.

AINT WET: I mean, this is kind of different than the conversation I had with Jeff Ihaza, who is an amazing writer over at the FADER and who has become a good friend of mine. This is a recurring theme that I think you’ll see in his interview: so many people who I have one connection with. Jeff, who wrote that article, was mentored by Mattthew Trammell, who I understand you have a connection with as well – and Jeff, he became my friend, which is really funny. So the interview with him that’s read by the public is just, like, a precursory glance at my friendship with him. But something that I was reflecting on this weekend, was that a friend of mine asked me to paint their kitchen. They have like a big, ugly, macaroni-and-cheese yellow kitchen that they’ve had since the start of coronavirus; they moved in like a month before, and they hated it. I’m just kind of that guy that people hit up for shit like that. You know, maybe I’ll turn into one of those older dudes that do odd jobs for people, and they like, buy them dinner or give them bread or something. Aside from the creative work I do, just like, on some shit, I’m just kind of a handyman at the young age of 25. And they ask me, Abe you’re really good at painting, you’re really professional. And like, as a kid, I really appreciated the art of painting, like oil paint or something – but my mom, she sold houses, she was a real-estate agent. And she was fifth-generation / fourth-generation in Brooklyn, so she really knew everything about these old houses; and she would bring me in to paint all these bedrooms and kitchens and stuff. I was young, and I kind of got to be this little painter boy that doesn’t really exist anymore, just like, painting houses. I think to say that AINT WET was also inspired by the utilitarian use of paint, which is so commonly associated with art. Even though I haven’t been able to put it into words, I was reflecting on it this weekend – there are these things that you associate with fine art, or having a high value, like a painting being worth a million dollars being sold at an auction. But there’s also the element of shit just gets covered in paint. Whether it be the subway I-beams, or it’s just like your crib and you get it dirty, or it’s like your bike or your car. The utilitarian use of paint is really something I was familiar with when I was young, and I find (it) really exciting. It’s so boring, and so normal, and everyone, in some way, shape, or form, has to interact with it. And to say that that doesn’t relate to the oxymoron of AINT WET – of course it does – it’s just that instead of cleaning something, you paint it. So me as a young kid, painting cribs or doing odd jobs, or sort of coming from that place in my life – sure. I think Hurricane Sandy, fundamentally, was the lightning strike of This is the name of this thing, and it relates to this other artistic pursuit I was doing with AINT WET as an art object, but the pre-origin of that – that was me as a semi-intelligent college student trying to make sense of the world. To go even earlier, there was just an inherent love for that type of work. It’s something I still do today, like two days ago, painting that ugly Kraft Macaroni & Cheese kitchen. So yeah, the paint, all that shit is really nice. And I got to go on the subway for the first time in a while; that was really nice too.

“Shit that you do yourself needs to learn how to exist in the corporate world in some way.”

SH: What was that like?

AINT WET: I feel like COVID has just shaken up my whole world – that was nice. I think I made the first AINT WET sign on a subway that I did in like six months, which is so weird to me, but also pleasant. The past six months, I’ve been able to be Abraham and figure out what’s going on in my life, and perpetually not have to worry about looking after this (brand) that normally I like. So yeah, it’s been okay. It’s been rough, but it’s been okay.

SH: What subway station was this? Just to clarify.

AINT WET: What subway station was I at?

SH: Yeah.

AINT WET: Oh, I don’t know. I hop out of the train if I see a sign, and I put it up, so I don’t remember — I can tell you where I was going or coming from. I was either leaving Long Island City, where a couple of my friends have a studio space, or I think we may have gotten lunch afterward; we walked from Long Island City to like, Bushwick, Williamsburg area, which we’re never in, I haven’t seen since COVID. There’s an amazing South American, traditional Mexican taqueria called Los Hermanos, with the conveyor belt with the tortillas –

SH: Yeah!

AINT WET: That place is sick. So I went there for the first time since COVID as well, with my friend Elijah, who’s an amazing artist; I got to spend some time with him – he writes, so he was doing some graffiti and I was putting up the sign. Shit was normal for a second. That was cool . . . but I don’t know, somewhere like Williamsburg L, maybe heading towards Manhattan to get on the Q train. We were just having fun; it was like a Saturday night. Lemme plug in my phone real quick, I don’t wanna lose you. I’ll bring you with me, try to make this worthwhile.

(Abe showed me a series of art pieces hung around his apartment, some of which were done for artists he’s collaborated with, and others of which were done during his college days.)

AINT WET: Like I said, I’m a little delirious because of that 5 AM shoot – which was amazing, it was so nice to be with everybody – but it’s cool. I think you’re going to get a more cerebral version of me, which will be funny.

SH: I mean, it’s been cool so far. That’s dope.

AINT WET: I’m glad.

SH: You mentioned this really cool dynamic about art in a utilitarian sense versus art in high-end institutions that you would pay millions of dollars for. I wanted to ask: given your childhood, do you almost value utilitarian art more? Or is it more like you appreciate both the same way?

AINT WET: I think I’m stimulated by utilitarian, I mean, accidental art. Just like, seeing things that didn’t happen deliberately blows me away. Like I saw a wall of graffiti that had, like, a color, but it was the wrong color red; there were two shades of red on top of each other. That could look like minimal art – like really beautiful minimal art – but this wasn’t done with the intention of being perfect, or smart: it just like, happened accidentally. I’d see that shit and lose my mind. I’d take a bunch of pictures and my friends would be like ‘what is this?’ Like “Oh, okay, it’s just some Abe shit.” Like, for sure, you hit the nail on the head. You can’t just say you don’t fuck with art. I certainly do love, for better or worse, that world, and try to remain versed in it – but I’ve never felt my own identity in it. And these are conversations I have with my friend Jasper Marsalis, who you might know through, I guess, music. Jasper battles with being a musician, and a painter, and someone who has issues with the Western or European art world, the structure that exists; and we fight about these things a lot. There are times when my perspective is frustrated, or angry, with European art or like a gallery system or whatever; and there are times where it’s just so fire that it doesn’t matter. I mean you grow, and it’s complicated, but I tend to lean (more) towards just some random shit on the street than actual paintings most of the time. It’s important – I can’t hate on it. It would be wrong of me to hate on it.

SH: That’s a good mindset to have. Going back to the way we started off, with your network – I know that you guys started off in close ties with people like MIKE, but recently I peeped that you guys did merch for King Krule in support of his latest project Man Alive. How has your network sort of expanded? And what has it been like to see your network sort of grow overseas with English artists like King Krule, versus where you started out in Brooklyn?

AINT WET: Sure. I think maybe from an outsider looking in it’s really easy to look at things that way, where it’s like – and this is due to, I guess, good marketing, or a good narrative being told through social media or something. But oddly enough, I probably knew MIKE like a year before I met Archy, King Krule. And the reality is, there was like, four years before I met MIKE and before I became involved with musicians, that AINT WET just sort of existed, and it was something that was absent of the music element; we had a different sort of manifesto. So we entered the music bubble . . . I think when you have a really strong offering when you’re doing something, you kind of move through that world so quickly. So if you look back at the music, and you can see this pretty easily, MIKE released May God Bless Your Hustle in 2017, and I had known him for about a year before that- but right after that, MIKE released Black Soap, which was something that he made in England; and I was in England with him. And before that, I think, like, Show Me the Body or Standing on the Corner had gone on tour with Archy. So I had been at a lot of their local shows, and him and I were already friends. I had sort of met him around the same time as everybody else. Even though you see this big musician that has a million followers, like Thebe, and you’re like Oh – like an elevator, you evolved to being able to work with this person, it really doesn’t work that way. Because I was definitely closer to MIKE, obviously, but I was getting to know Archy as I was getting to know people in the circle. So these friendships really grow in a more organic way. I was getting to know him at the same time as everybody else, and . . . maybe – it’s not to say that – there was no need for the AINT WET touch until there was, because he’s an older musician and they have this huge structure of how he does things, like his brother, who’s an incredible artist, kind of art directs all of his projects. But yeah, during the Black Soap era we were hanging out with him a lot, because his friend circle is really strong with MIKE’s circle that you see now with Jadasea, or Rago, or Redlee, all these UK-heads who are really amazing. We all met at the same time in 2017. And then Malcolm, who would kill me for saying his name, but he runs Matter Research. You should honestly reach out to him after this interview if you’re trying to do another one, because he is like the OG in the UK. He’s the one who connected MIKE to us, and before that he worked with Wiki. He’s not too much older than us, but he’s just around, and knows everybody, and brings this circle together. So yeah, I knew him in 2017. Honestly, working on Man Alive, which was an honor, was something that came through his record label. His record label in the U.S knows me because of some other artists I work with; they knew that we were close, and they were like I don’t want this to feel ingenuine — Like I’m just gonna be straight up, if we do this ourselves, it’s just gonna be like some marketing shit. We reached out to Archy and he’s like if you do it he’s cool with it, like can you please do this to make it feel more authentic. And I was like, you know, ‘of course, of course I can.’ But yeah, this kind of goes back to this ongoing theme where I really feel like me and Archy could have never released anything ever, but we’re homies, like we’ve been friends over the past couple of years, and we continue to – like, I’ve seen his life progress; I’ve seen him become a father, you know, these are beautiful things. With Thebe it’s the same thing, because those are the two sort of bigger names that the public would be like that existed before in some way. I’ve known him for several years as well, like, I helped on Some Rap Songs visually, a little bit, but not to where I would post on IG. It doesn’t matter because you’re just helping out a friend with a piece of something; they’re calling in a couple ears, a couple eyes, to look at something. It doesn’t really work like this – like a ladder – where it’s like “AINT WET’s gonna do some shit with Jay-Z” – I mean, that would be lit, but it’s almost just how the world unturns. Like even with Sage’s stuff, that’s been in the works since 2015, and I guess you just saw the first public display of AINT WET working on it, but me and Sage have been – you know, we all come to each other for advice. Like ‘hey, what do you think of this, what do you think of that.’ It’s just like anything else. It’s just like all these moving elements, just friendships, before it’s public. I guess the real answer to this is that I’m honored that I’ve reached a point where it goes beyond just being friends, even a record label or someone who does have capital, or does have money, can give it to people in their community – and like, do something that is more genuine. And I hope that happens outside of my community. I hope that more record labels recognize the fact that they do control commerce, and they can put money in the pockets of contributing artists, or artists in their circle, in a way that can be productive, and that should just be something that happens all the time. There’s all these budgets, constantly, and it’s so much easier for a record label to do stuff inwardly than it is to reach out and be like ‘Who’s your homie?’ Like Oh, I’m gonna put on my friend to do this. So yeah, there’s two parts to this: where it just sort of happens, and we’ve reached a point where a record label can recognize our existence. And that’s fantastic. I hope that continues to happen more. Because shit that you do yourself needs to learn how to exist in the corporate world in some way, just because every young creative person in this world needs to know how to tackle those things; If you have your friend there as a liaison, it can be really productive. So those are two kind of important notes, I think.

“Yeah, it’ll make sense. It hasn’t yet- but you know, through the music, that’s the time capsule.”

SH: Yeah, that’s real. I wanted to shift to a theme that I saw really prevalent in your FADER interview, and that was the islamophobia angle. After 9/11 New York City really zoned in on that, and I feel that you’re in a conversation where you’re sort of representing NYC in what you do, giving sort of an authentic look at it – how has that sort of clashed? And I know it must have been a real challenge, but how have you persisted through that?

AINT WET: Well, it’s crazy. That article was, maybe, in 2018,and those themes were true then, and the themes I’ll speak about are obviously true now as well. But I think it’s really important for everyone to address their own internal conflict. It can be a myriad of different things. For me, I can attest to my Islamic background, and growing up as an Arab-American in New York, and the difficulties of that. But these things are also a gradient, where it’s like- I had a lot to say about the Twin Towers, and I still do; that’s a piece of iconography that I hold really personally. But I think – and you can see this through my art – that helped me to gain some sort of understanding of oppression at a young age. But oppression is also a gradient, where, being a lighter-skinned Arab in New York is difficult to a certain extent, but there are so many other different people with their own experiences. Through collaboration, I’ve always felt that I try to take a step back from it being about my identity, also trying to help any artist I work with to express their own narrative, their own identity. And it’s not about the struggle either; it’s also about addressing the amazing quirks and elements of your background and your experience. And I think that’s another way to combat the pain. It’s not just like oh, the world is on my shoulders because I’m Arab and people call me Osama and they use derogatory terms and they make fun of my religion and they tell me to eat pork – you know, all these things. It’s also like: Every time I go to a corner store, like a deli in New York, It’s someone who either grew up in Alexandria, Egypt next to my dad’s neighborhood or somewhere else, and we can share this moment and speak in Arabic quickly and feel like we have this kinship, instead of it being like ock-at-the-deli, like here’s this Arab man in a black neighborhood. For me it’s like respect, but it’s also like kinship because we’re from the same place. So I think the positive is really important, but also not just making it about yourself is also important where there are so many other people. Another theme you might notice in my circle of friends and collaborators is – I guess ‘Identity Politics’ are sort of the worst words for it – but trying to understand who you are. Because we are privileged enough to have a platform, and be creative, and be able to speak about it, but we also have our own traumas we’re working through. So visually, to provide that for someone else is always important, and kind of knowing your place as well, and knowing when it’s really not about you – but I think that, to bring it contemporaneously, like modern-era, we’re in a whole different stratosphere. It’s hard to think about the towers falling when the entire globe is in pandemic. Or when there’s continual civil unrest because of the perpetuating isolation towards African-Americans in America. There’s so much more modern problems that you just deal with as a person, or witness, or try to support, or understand that you’re facing, that the towers is just sort of old tech at this point. And I feel that we’ve worked through it, and luckily we’ve had so many artists talk about it in all these different ways, like DIPSET, or Jay-Z, or whoever. But now I feel like we’re really faced with a really modern- and luckily I’m a little more sharp, and I have the vernacular and the platform to figure out how I’m going to get through this situation, which is humanizing, and it’s cool, because, like I said before, I’m very lost – and I’m glad to be lost – because there’s a lot of work that needs to be done. I think I’m a very quiet person; like, you haven’t heard much from me on IG through all this, whether it be self-promotion, or commemoration, or the mourning of. That’s just not how I behave with technology. But I think all of these things will dramatically affect the way I creatively occupy space moving forward. And when new projects are published from us, they’ll be felt and understood- and we’ve worked on stuff, we’ve worked on Aya Brown’s website over COVID, we helped Pink Siifu with his website as well, we’ve worked on Standing on the Corner’s album rollout, and MIKE’s album rollout as well. So we’ve been active, but I’ve been off the gram. I’ve just been kind of like, you know, focusing on me – and that’s been really nice – but I’m excited to see what AINT WET becomes post-COVID, and this new decade of shit that’s gonna be fucking crazy. I can’t stop thinking about how crazy shit is, and that’ll be beautiful to watch, myself grow.

SH: I’m getting this theme, from that answer, of sort of speaking through your work instead of signaling using social media. I wanted to ask, if it has evolved, how has that evolved over the course of AINT WET, or your personal past, with how you’ve grown up in this artistic context?

AINT WET: Sure. Something I believe really deeply – and this goes beyond art, it’s just communication – is that actions speak louder than words, or, like, showing, relative to telling. It’s a lot of shit you can cap, but the act of doing is really the real deal. Like if you don’t say it and just do it, then it speaks for itself. I mean I hope that my message speaks through my work, I feel like it does, but as far as how that works, it’s complicated. Because for example, Weight of the World, coming out in the middle of coronavirus, seems like it can be directly about COVID and everything else going on – but low-key, Mike had the name for that album like a year ago. You know? Mike’s had shit to deal with. What’s beautiful is that these ideas are a year old, and just the way things are formed- like we create things before it’s in the public. There have been loosies, like if you’ve been to a live show you’ve heard a couple of the songs before, shit that probably didn’t end up on the album. But those themes and those concepts existed. I don’t think we’ve seen from anyone yet, like a post-COVID, post-2020 type project that was made during this shit and is about this shit directly, not even like a loosie or something – but I’m so stoked. Not even for myself, I’m just gassed for my peers to be like ‘this is us reacting to, you know, this.’ So I don’t think anyone’s published it yet, but I think everyone’s sort of feeling it out, as am I. I think the next body of work you’ll see from me, whether it be an independent AINT WET collection or something I’m working on with somebody else, is gonna be considering those things. And you know, I think the things you’re seeing from us now are equally valid, because we’re all such introspective, sensitive people. We’re constantly feeling out what’s going on, whether it be racially, or politically, or socially, or emotionally, or, you know, familial shit. Yeah, it’ll make sense. It hasn’t yet- but you know, through the music, that’s the time capsule. I couldn’t tell you how good or bad 2017 was, but I go back and listen to all the music that came out during that era, and it brings me right back to whatever was happening. And I’m sure we’ll look back in a couple of years from now and do the same shit with whatever happens. And there are those who have really taken it by the horns, like I mentioned Aya Brown earlier. Those that did really jump in front of this shit as the first up at bat to talk about it have done an amazing job. But not all of us are that quick. And I feel like some of us needed to digest more. Like, this is not just a scene or a group of people, the world will react to this. To bring up 9/11 again, like, how many fucking post-9/11 movies were there? Obviously, films aren’t being shot, and things aren’t being made – maybe they’re being written – but there’s going to be like a million things addressing the stuff that we’re going through on a pop culture level, immensely, over the next five to ten years. A hundred percent. Each decade has a vibe, like you can say the 80s to someone and they close their eyes and get the 80s; and it’s cool to be at a creative point in my life where I can help form what the 2020s look like. Like, that’s amazing. Maybe in 2030 I can be a small piece of the visual identity of this decade- like fuck yeah, that’s like the most motivational shit in the world, you know? I hope that’ll get anyone to continue making shit. We’re at the bottom of the decade, like, let’s go. You have ten years to make something that is memorable.

SH: Yeah that’s actually a great way to think about it, I never thought about it that way. I meant to ask this question earlier on, and I think I messed it up: But how does this metropolitan setting of NYC generally inform your work? Like do you just walk around and get inspired by stuff? I think what I’m really asking is can there be AINT WET without NYC.

AINT WET: Great question. It’s one of the hardest questions I face internally, personally . . . I think of course it could. You asked earlier about King Krule, England – I’ve spent a lot of time in England, London specifically, but then Los Angeles, and we got homies in Chicago – the movement is there. We got buddies all over the place. And I go to all these amazing cities, and I spend some time with their infrastructure, their subway systems, the way their stop signs look different than ours, all the nuances. I try to find the New York shit in every city, where it’s like, those things that call out to me like this is the sauce, this is the substance; I always try to find that shit when I’m somewhere else. Like, what’s the thing that’s in every Chicago deli? What makes it different? They sell hard liquor at the deli(?), like yo that’s crazy! In LA, the fact that there’s so little Middle Eastern food blows my mind. The Italian food is different, and then the South American food is insane. It’s just these little things. When I was younger, I used to want to find the New York in places, but now when I go somewhere, I try to find – I spend time with people who’ve grown up there, people who’ve lived there – the thing that makes it their place. And I feel like I do. I just love cities and urban spaces in general, so I’m naturally drawn to that on a primal level, beyond the nostalgia or iconography of New York. I just love infrastructure, and how beautiful and soul-crushing it is, as depressing as that might sound. To me – and I love being in the country as well – but that’s all I know. And I think that’s unfortunately the way that it just kind of is, and I like finding the beauty in it as well. So you go to these other places and get that sense to become a part of it, but one internal conflict that I have is, it’s amazing that you found it, but does that give you the right to speak about it? Because it’s not your place and it’s not your space. Maybe if you lived there for ten years or some shit, but we’ve, like, attacked gentrification for years. Like ‘are you really from here?’ ‘What do you know about New York? I didn’t want to be that person in LA, in London, or in Chicago, because I’m from New York. I’m not going to be the representative of your place. That’s the beauty of friends, like, you can address those themes through your friends’ art. Like when I work with an artist from LA, it’s an opportunity for me to sprinkle some of the little things I found into it, or vice versa> But I don’t know. We’ve always joked about, maybe I’ll do a British subway collection- if you dig back in AINT WET’s archive, I spent a year in Paris; I tried to make a clothing collection about Paris, and I did an okay job, but I was a much younger person. Like- would I take on another city the way I have with AINT WET? Maybe. Maybe if I think I’ve got it, or maybe if I’m working with another brand from that place, and there was like a platform for it. For me it’s more about finding the beauty of that thing. So when you work with commissioned shit- like, if I were to be asked to design an Air Force 1 – not that that has happened, but that would be amazing – before I thought about what I could put of myself into that Air Force 1, I would need to understand the history of that sneaker, and why things are the way that they are and how it relates, and then be able to talk about it. So through collaboration, these global things, I’d love to address them, but I’m not ready to and I want to understand them better. But as Abe, as Abraham Mohamed El Makawy, the legal ID that travels to these places, I really spend a lot of time looking at the garbage and shit, the cement, the tiles – the same thing I do here, just getting excited about the mundane beauties. It hasn’t affected the art yet, but maybe. I don’t know.

SH: I’m getting this thing from you about appropriation versus appreciation, and I want to ask what you think the line is. Do you think there’s a definitive line you can cross from appreciation into appropriation, or is it sort of vague?

AINT WET: It’s tricky. Tricky question. It’s all about how it’s charged, in my opinion, you know? I think that you’re totally allowed to appropriate the things that oppress you, and the things that hurt you. You really shouldn’t appropriate the things that you don’t really have a connection to. And that’s something that you can’t write on paper; you can’t write a road map for that shit, it’s more of an internal thing. And that’s why it’s good to talk to people. If you want to do something that’s out of your comfort zone, talk to somebody. If you’re going to involve a conversation with blackness in your art, and you’re not black, talk to a black person. Speak to your friends. Speak to your peers, and hopefully they’ll be straight up with you, they’ll be honest. And that goes for anything beyond race; that can be for something as simple as when some brand or some shit tries to jack New York, and it seems really phony, and it’s toy, and it’s fake – you’re gonna get flamed. Like this is not who you are, this isn’t you. And you can appreciate it – of course you can – but to tap in with something . . . I’m super sensitive about it; I’m super judgmental, like, I critique everything. I’m judgmental of my peers, you know? But at the same time there’s also this kind of a place for it as well. And it’s all about your mentality, like I said. If you are at peace with it and the world might not understand your peace, that’s your opportunity to tell your story. Drake is a classic example, and I don’t know too much about Drake as a person, but if I was thinking about him critically, I see this person who grew up in Toronto juxtaposed with New York City, urban America really; and I see someone who is mixed, which I can identify and understand, and what it does to how it skews your identity and the thing that’s yours. And I think the conversation about Drake you always see is like yo, Drake, why are you jacking New York flow, or why are you jacking a London flow; Why are you on a trap beat? Why are you just going into all these elements of black culture and acting like they’re yours? And I’m not gonna like, co-sign Drake by saying this, but I think it’s just a good analogy I’ve used before, where it’s like you have this person with an identity of being a black American. And he’s biracial and he’s not from America, but that’s the culture that he is a part of, through pop culture on Degrassi or being a rapper or whatever.He could fully just be doing it for bread. But someone else can be in his same position. I can understand, I can sympathize with him, if I was his lawyer, I could defend him in court with this argument that he is learning his identity. He’s confusing space in this world through these different things, because it’s something that is made up of so many outtakes, and views, and perspectives. So, you know, him rapping in Puerto Rico is valid, like, there’s afro-Puerto Ricans. He’s not an afro-Puerto Rican, but maybe he’s not been treated as what he is, and he’s so scrambled as to what his identity is. It could be cap, but I’m saying that someone like him can be in that same position. There are people all over the world that are trying to understand themselves through different things; and I talk about islamophobia, but go to Egypt to visit family, and I’m walking by myself, I’m looked at as an American. My own people don’t fuck with me. The same can be said for if someone was African-American, and didn’t know their ancestral heritage: your identity is separated from the location. You could even be white and live in New York, and have a better sense of the world, and you can visit your cousins in the South and be like I don’t get these people, we don’t see each other eye to eye. So I think there are boundaries to these things. If it’s a form of understanding your own space, once again, talk to people. Understand what’s for you. And when you’re in a creative space, life if you’re an art director, I always say that I try to be a megaphone for somebody else. So when I do a bunch of research on a Nollywood film or try to understand Santeria, these things that I have no connection to culturally, I admire, and I think they’re amazing, but I would never include in my own work. I’m doing that because I’m trying to become a visual amplifier for the thing that I’m working on. And those things have themes from there – like how do the title cards look in Nollywood movies? Lemme watch a bunch of Nollywood movies; lemme go on Youtube and watch a bunch of clips. And I reference that in the FADER article, but that goes in anything. I’m never like well, I am appropriating these ideas or these themes that aren’t mine – because I’m not doing it for myself. I’m doing it so that MIKE’s shit is more authentic. And I’m learning, and I’m growing. Now I have a different understanding; even if the fans are like ‘that’s some funny text,’ I ripped it from some movie. That shit’s like sampling. I mean, I’ll never tell you if I sampled – maybe if I’m trying to flex – but you dig, and you find that past references are sick. So I don’t really think there’s a place for white people in hip-hop. But there’s a line to all that shit. So I don’t know. Just communicate. Talk to people. Accountability, a hundred percent. But also, like, learn. Don’t publish some shit before you do some research or get educated. I also think that I’d love to see people just not reference anything. I kind of feel like that’s where I’m heading at some point in my life. You know, all these discussions about appropriation, and referencing – what if you tried to just make shit that was devoid of any callbacks, winks, references, nods to shit . . . Can we get to a point culturally where we can just progress further? Maybe that’s a good outlook for others. I think there’s a laziness to references, you know, depending on what exists already. So that’s my kind of introspective alternative, it’s a little edgy, but yo – why don’t we just stray away from the references altogether? What if we just move past that and find something else? That would be amazing. That would be sick.

SH: That would be. I wanted to ask specifically about your website, which is actually very cool – and with mine, of course, I use, like, WordPress or whatever – but just from one web developer to the next, I find it crazy that you emulated the entire thing that you refill your MetroCard at. And this is just the way you guys emulate New York culture. So I wanted to ask, with the website – who developed it, what went into it, and then also, specifically — you guys sell candy on the site, and other little tokens that remind you of NY. What’s that about? How did that come into place?

AINT WET: Sure. I mean, those two questions kind of go hand-in-hand. To be fair, and I think this is pretty clear when you read the FADER article, I’m definitely like the bullet sponge for AINT WET, but there is a second half to this party, a second half that doesn’t want to be interviewed, a second half that doesn’t like talking about their shit, which is my best friend Michael Saunders. He’s amazing. He’s not here today because he’s getting ready for an interview with Google, like, good luck Mikey, I hope you get the fucking job man. But he’s a serious coder. And like the FADER article you referenced, we were going down two very different career paths; I was going down the art path, he was going down the computer science path. That was amazing because we were both pursuing our dreams. But AINT WET was an opportunity to keep on doing something together, and it was printing for a long time, we printed together. And then Mikey was like I don’t wanna print anymore. But I still continued printing, and I was like okay, so what can we do together still? And he was like well, I’m not really studying web design, but I think you would really fuck with it, because he’s studying true, hard, computer science, beyond HTML or C++, you know, like real coding. Not to attack web designers, but the shit that is more theoretical. So for fun, he learned backend and frontend web design. He never really took a class, he just learned how to read code, like Python and a bunch of other shit. I design and sitemap all of the sites, and come up with the navigation, and how it works for mobile, and the spiritual design of what it means, how it works- we should really make a proper AINT WET published post about the websites we work on, but the same way we do album rollouts for people, or t-shirts, whatever, we make websites for people. Like, it’s a part of our thing. We call ourselves Interactive Design Mark Outfit, so as to cover all the bases of what AINT WET does. And I think that digital infrastructure is as important as everything else – we just want to make the shit that exists between the mortar and concrete. So yeah, Mikey, through his love for computer science, we built the current version of the AINT WET site. It’s important to note that the original iteration of the AINT WET site was coded by my childhood friend Joy Ling and her associate Tom in 2017 before we overhauled the site to accommodate other sellers and features. Both the original build & the current build were very intuitive to me that if we were building an e-commerce store, I would reference the first touch screen I remember ever using, which was that, and I thought it was perfect; it was so thoughtless but also so thoughtful to make like a one on one representation, of AINT WET being that. We also have a new feature, where if you buy something, you can get a receipt, and it’s similar to the MTA receipt, and you can, like, print a receipt. I found the font – it took me, like, fucking months to find the font, but it’s a cool little Easter Egg. We’re always adding new shit – I don’t think people realize, but we’re constantly finding out about the MTA kiosk and then adding it to the site and making it more accurate or some shit. And then to answer your question about the snacks, that was referencing, like, yo, I’m selling snacks, does anyone want to buy snacks for a dollar on the train. But the reason that it’s there, and it ruins the fun, is that when me and Mikey are working on the site, we need to beta test if it’s working. So we originally made an item that was worth one dollar, and it was just a blank tile. Mikey would buy that from his PayPal and it would go to the AINT WET PayPal, to see if it worked. And one day, without telling him, I just changed it to Welch’s fruit snacks and Famous Amos cookies. And he’s like bro, this is hilarious, because that is the one dollar thing you buy on the subway. And I was like facts, we’re gonna leave it on the site. And he was like really, what if someone buys it? And I was like I guess we have to send it to em. It’s like a nod back to the web design process that we went through, but it’s also me thinking critically about these things I’m so familiar with. It’s intuitive- originally I was going to make it a loosie cigarette, but I thought that maybe I would be sending a cigarette to a child or something, I don’t know. We just love it. That, to us, is the most pure form of collaboration, more than me just designing a T-shirt and him printing it. I’ll hold the site dear forever. That’s a little cutie; that’s my baby.

SH: Where do you see yourself in the distant future?

AINT WET: Like straight up, in the distant future – and this is what I’ve been doing through COVID – just like Sandy, just like anything else: just rebuilding. We’re moving into a new space where we’re trying to open up a store; we’ve been trying do do this for a year – it’s called General Waste – for the public, for, like, young kids to come be creative, and fuck around. It’ll be in Red Hook, where we grew up, and that’ll be amazing. There’ll be a print studio, the office space for me and Mikey to work- what’s nice is that even if he gets this job at Google, the importance of having an art space or studio. So a lot of attention, for us, has gone to that. Like, I live in an apartment with roommates, Mike is in the process of moving out of his family’s home . . . This space will be essential to the next steps in our journey – which, I know, is completely removed from setting the tone for the decade, who knows, maybe it will – but we’re gonna really try and build a community center, a little studio space that’ll be semi-open to the public, we’re gonna share it with MIKE, MIKE’s gonna build a recording studio — it’s gonna be sick. And I mean, that’s the first step, having our own means of production, not having to depend on going into someone else’s space to do some shit. We’re gonna go off the grid and have our own little enclave. So yeah, building the base, building the headquarters, that’s the first step – and then we’ll take it from there. Having this space will hopefully allow us to be there, whether the next generation of young creative people want to come or not, to just have a space where you can talk to us, and we’ll be there. So it’s like a little hermit crab. We’re just growing, you know? New shell mode. Every element of what I’ve said earlier is really- there’s a lot of growth that I feel that I’ve done through quarantine, and being separated from shit and being able to re-evaluate it. I think there’s been some internal growth. And I’m ready for external growth.

You can learn more about AINT WET on their website. Meanwhile, stream Weight of the World.