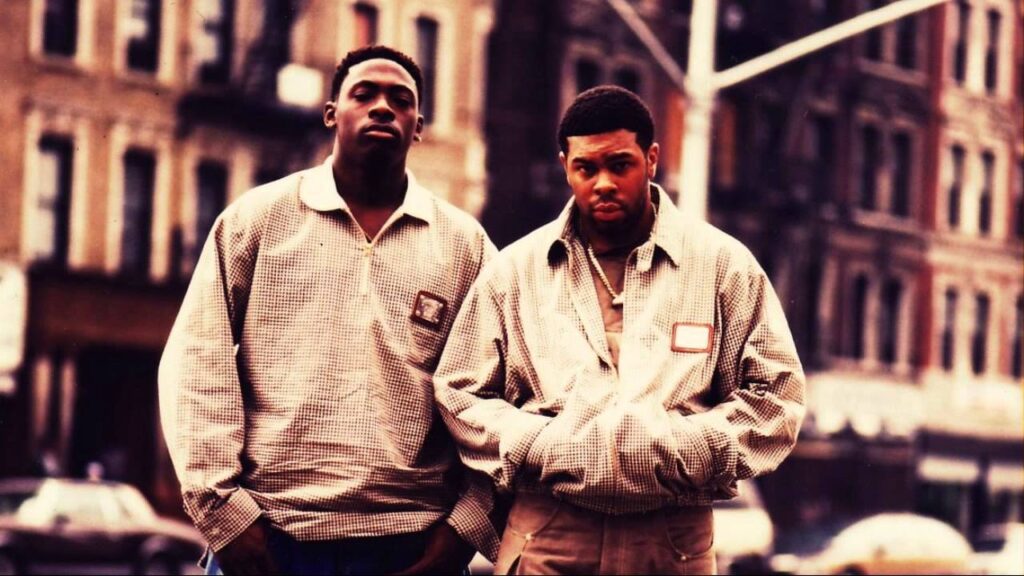

All of the producers who worked with Nas (center) on “Illmatic” pose after a studio session. Pete Rock (the only producer not pictured) produced one song on the rapper’s 1994 debut – “The World Is Yours” – which went on to pioneer the presence of jazz in contemporary hip-hop.

SAMUEL HYLAND

In his autobiography, Malcolm X describes 1940s New York as a city comprised of scat-singing, finger-popping, and “re-bop-de-bop-blap-blam.” In Illmatic, the same New York – 50 years ahead – is dubbed the “dungeon of rap, where fake ni**as don’t make it back.”

The era of the big band is not the only one to undergo a similar fate. Long before Duke Ellington first walked onstage at the Colton, the institution of slavery amplified what would become blues music – until, centuries later, Bob Dylan took the stage at Newport in 1965 with a stratocaster, and the blues symbolically gave way to rock & roll. Even further, for much of the time before the discovery of America, contemporary music primarily existed in the church – until even that was eventually eclipsed by the secularism of the Renaissance. In the case of jazz in the 1940s, the same principle rang true: time was ticking. Not necessarily time on Earth, that is, but simply time in a spotlight soon to be taken by the rapper – who had no say in reversing the process – even if, like Nas, he was the son of a renowned jazz musician.

Where the determining power did fall, however, was the hand of the producer. Included in this authority was the final word as to whether genres lived or died.

What did Pete Rock do with this jurisdiction? The improbable: he lifted jazz up from its deathbed, and into the 21st Century.

Three minutes into a 1994 interview with MTV’s Fab Five Freddy, the camera cuts to the birthplace of such a feat.

We’re in the studio. There are cup-bearing revelers pacing back and forth. There are 1-year-old babies seated atop large vanities. In one corner, somewhere within a maze of mixing boards and synthesizers, you can find the turntable making all the racket. It’s Pete Rock’s basement.

“So the beats, man, this is like – where y’all make the music?,” the interviewer asks.

“This is where we make all the flavors at,” responds C.L. Smooth, Rock’s then-associate.

The camera then pans to Pete, who, hunched over the aforementioned setup, bops his head to chopped and screwed string, percussion, and vocal samples compiled from various different records.

When later asked to identify a “main ingredient” of such prowess, he offers: “totally bouncing off where we’re coming from.”

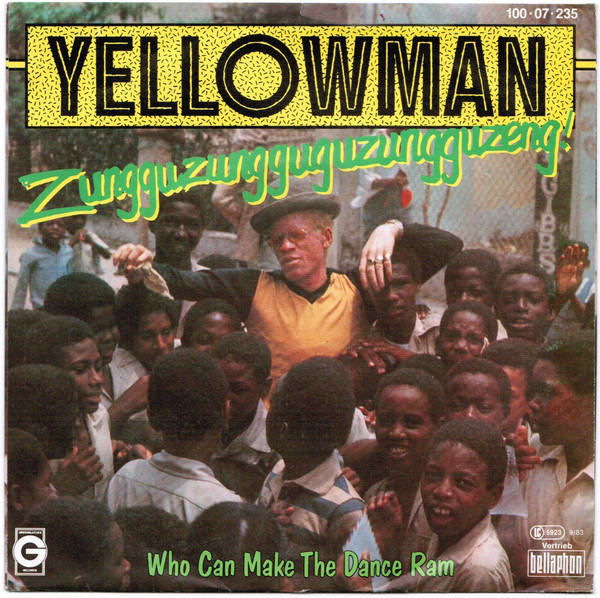

Pete Rock grew up the son of Jamaican immigrants, one of which he regularly accompanied to a DJing gig dominated by countless heaps of jazz reggae – so in the first track to ever see his production (Mood For Love by Heavy D & the Boyz), such a background is thrown in the face of the listener.

It opens with the jazz factor: a boisterous, echoing brass rendition of the original reggae sample’s guitar riff. Then, the Jamaican: in articulate, yet offsettingly fluid patwa, two male voices scat above the bassline until one muses: “A man once told me love is the best thing that a man could have.”

The “main ingredient” – homage to one’s heritage – is discernible over decades of work. In The World Is Yours, it reveals itself in the somber jazz piano of Ahmad Jamal. In Big L’s Holdin’ It Down, it peeks through the cracks via a looped one-second Dankworth sax interval from 1963. And today, with LPs like To Pimp A Butterfly, it’s all but doubtless that when hip hop first took hold of jazz – it never let go.

Pete Rock did not change jazz itself. He simply rebranded it, repackaged it, revitalized it – the difference being that it was accessible. With jazz no longer steering an independent cultural presence, the producer allowed its journey to continue, hip-hop in the driver’s seat and jazz riding shotgun.

Matt Trammell is a music journalist who has appeared in the New Yorker, Billboard, and The FADER, amongst various other publications.

“Genres don’t really die, they just get absorbed into the larger contemporary practice,” he told me via email.

He referenced trending singles by Dua Lipa, The Weeknd, and Doja Cat as testaments to the cycle, citing that all three tunes are of the disco fold despite people saying the category died decades ago.

“We don’t call them disco songs, because we don’t really identify disco by itself anymore,” he wrote. “We just use its style and technique to make what we want to now. Jazz won’t die as long as people remember what it sounds like.”

“Jazz won’t die as long as people remember what it sounds like.”

– Matt Trammell

In a way, Pete Rock was doing exactly this: ensuring that we remember what it sounds like. In the words of Mr. Trammell, “people can recognize what jazz sounds like, but they don’t really know modern jazz musicians by name.” When considered in this sense, it’s apparent that jazz had to change as music did so itself. As any genre begins to step out of the limelight, the artist, by nature, must take that step with it – but in the case of jazz specifically, the genre was oriented towards its sound (rather than its musicians) long before a changing musical climate forced it back into that sphere.

Take the 1950s for instance. In an era like that, music was not as much about the object as it was about the ambience. A vinyl was not spun to be fixated upon. It was spun to create an atmosphere in which something bigger would take place, the likes of a social gathering, a convention, or Sunday dinner.

To quantify the difference between then and today, I looked into the complete list of Billboard chart-topping LPs for the year 1957.

There were only nine albums – five of them soundtracks – some of which remained in the number 1 slot for up to four months at a time.

Take the list for a year ago, though, and you see something entirely different: Compared to 1957’s nine, forty-six records populate the table, the longest top-spot tenure of these being a mere three weeks.

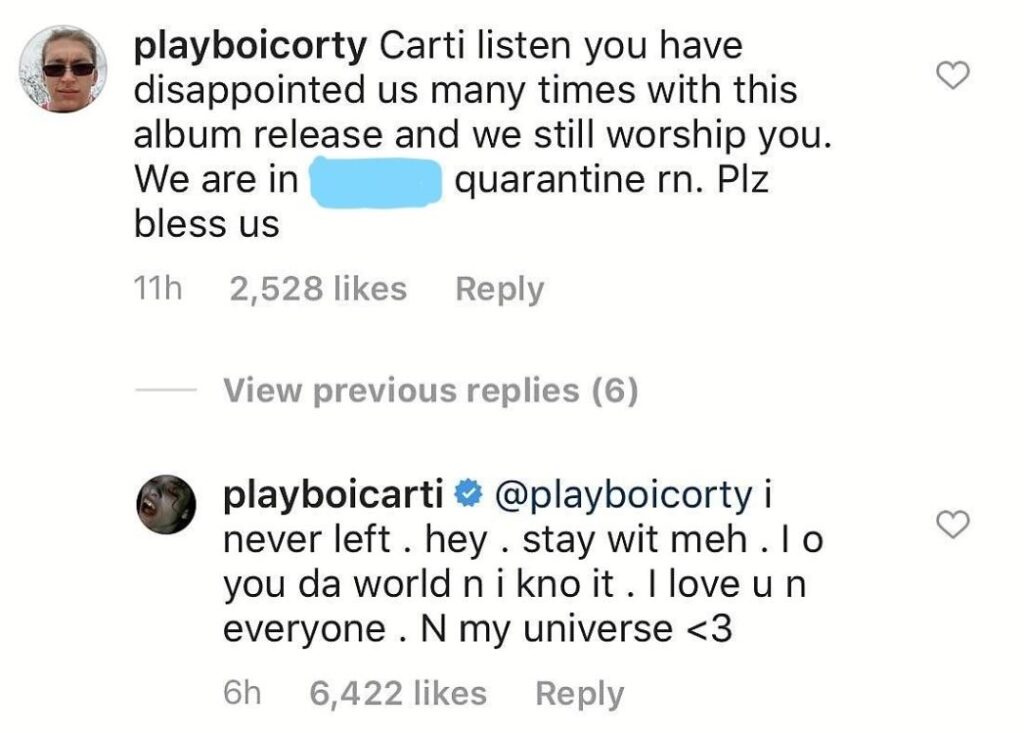

The provocateur: a “microwave society”. As material obtainment became more realistically immediate, consumer culture slowly clawed its way out of the womb. You didn’t see people mailing John Coltrane “*WHEN * NEW* +MUSIC**DROPPING**:)!!!!” (taken from a Playboi Carti comment section) in 1963, nor did you see theories upon theories of album rollout schemes grace the agenda of a Johnny Hodges fan club meeting in his heyday – because people cared more about how the music made them feel, as opposed who specifically made it. If the LP made America feel good, it was going to stay atop the charts for as long as it took for something else to have the same effect. If the opposite occurred, it was on to the next.

Today, you can have a collective sense of urgency attached to music because it has transcended atmospheric purposes. No longer do we spin (or even own, for the most part) vinyls to merely set the mood – as individuals, we identify with a certain sound, seek it out, and consume as much of it as we can in order to satisfy whatever it may be within us that must be quenched. It is when we are without such nourishment that we begin to grow impatient. That is what constitutes no album surpassing a three week stay atop the Billboard 200 – America isn’t listening to the same LP for four months straight, because America needs new music now.

For jazz, that immediacy manifested itself in a digital rebirth. The new stage for the big band? Hip-hop, electronica, and any other genre you can think of. The nucleus, though: still the sound – and more importantly – the feeling it emits.

Melbourne-based DJ & Producer Prequel is a prime example of what this looks like in a modern scope.

“In terms of my productions and their incorporation of Jazz elements I just try and find things that evoke a certain feeling,” he told me in an email. “I guess the fact that I incorporate Jazz into more of a “dance-music” arena is my modern spin on it, but also with certain elements in my productions I use a lot of improvisation, which obviously comes from my (limited) Jazz knowledge.”

Listen to his 2018 EP Without You, and the latter is perceptible. And Though It’s Been Too Long begins with the solemn keystrokes and unorthodox drum patterns that have long embodied jazz as a genre – but by the six-minute mark, the DJ manages to incorporate fading vocals, dissonant electric guitar riffage, and a groove-heavy synth bassline reminiscent of music’s newfound electronic presence. In The Song I Said I’d Make For You, another track off the Without You EP, a saxophone permeates the house background established within the first two minutes, carrying on through its entirety. The ideologically opposed natures of jazz and electronica come together not to form something tense, but refined in an artistry that disregards preconceived discord.

“Jazz will never die,” he added to the email. “Most music is based on Jazz (Soul, Funk, Disco etc). It continues to evolve, get re-interpreted, find a wider popularity again and be continually fused with other genres in new ways.”

In the music industry, no one ever truly disappears. Death is impossible. New life is always within reach. Everything is infinite.

For jazz, though, the question persists: Is Jazz Dead?

A look at the genre by itself points to the affirmative.

But that’s surface-level.

Take a peek at the deathbed many built for it years ago, and you’ll find nothing but a shedded hospital gown, a saxophone, and a postcard from the present.

BELOW: The entire email interview with Prequel.

Note: In every interview I conducted for this article, I asked about both the “death” of jazz music, and the relationship between music and society. Everyone had something very interesting to say – and although I could not include them all in this article, for a forthcoming piece, I will publish every interview transcript.