🌐 🌐 🌐

There is an indeterminable point in every creator’s career where influence and intent part. This leaves consumers – the supportive ones and the unsupportive ones alike – to make sense of the debris.

SAMUEL HYLAND

One of the counterculture movement’s most commonly recited fables centers around Altamont, a free admission 1969 concert that was hyped as “Woodstock West”: somewhere near the midway point, as the Rolling Stones blazed through an inspired iteration of “Under My Thumb,” a violent jostling commenced in the anterior section of over 300,000 concertgoers. Hells Angels, a brash Las Vegas Motorcycle gang widely known (and feared) for its thuggish brand, had been tasked with running security for the evening’s festivities – and their radars were locked in on Meredith Hunter, an African-American 18 year-old in an avocado-colored zoot suit. When Hunter attempted to jump onto the stage with other fans during the song, one of the Hells Angels grabbed his head, delivered a swift blow to his face, and chased him back into the general assembly area. About one minute passed before Hunter would once again try to mount the stage, this time with his girlfriend, Patty Bredehoft, tearfully begging him to calm down. “I saw what he was looking at, that he was crazy, he was on drugs, and that he had murderous intent,” then-Grateful Dead manager Rock Scully recounted. (Scully was able to see the entire melee clearly from the top of a truck.) “There was no doubt in my mind that he intended to do terrible harm to Mick or somebody in the Rolling Stones, or somebody on that stage.”

Back in the crowd, Hunter extracted a .22 caliber Smith and Wesson pistol from the inside pocket of his jacket. Widespread video footage of the event exhibits Hunter as a lustrous green figure at the center of pandemonium, standing in symbolic juxtaposition to the rough-edged monochrome of the Hells Angels’ leather jackets. Upon seeing him reveal the gun, Hells Angel Alan Passaro took a hunting knife from his belt and stabbed Hunter five times in the upper back, killing him.

‘Under My Thumb’ is a hopeful song, and the image of it soundtracking such a wretched incident is perhaps what affords the ordeal its inconspicuous eeriness. Just as Mick Jagger sang “It’s alright; I pray that it’s alright” into the microphone, jovial bass fills and lively electric guitar shrieks emulating the optimism of his plea, the sudden horror of his audience moved to overtake what was being performed on two fronts – one of them being very literal, with audible chaos prompting the musicians to stop mid-song, and the other being more figurative, with the dark, murderous crevices of human nature casting an inescapable shadow over the idealistic utopia that was emanating from the platform. The band did no wrong that evening, but it puts things into great perspective to question the legacy of their performance at-large – which were the mid-Altamont Rolling Stones remembered for: the peace they sang of, or the bloodshed that erupted as they were singing of it?

Much of the Rolling Stones’ reputation, up to that point, was defined by the kind of polarizing essence that cultivates both adoration from youth culture en masse, and hatred from the elder generational makeup that preceded it. Writing about the impact of Elvis Presley for New York’s Village Voice following his death in 1977, Lester Bangs mused that “Lenny Bruce demonstrated how far you could push a society as repressed as ours and how much you could get away with, but Elvis kicked ‘How Much Is That Doggie in the Window” out the window and replaced it with ‘Let’s fuck.’” The Rolling Stones, led by the jarringly lewd, raspy-voiced frontman that was Mick Jagger, vigorously furthered this string of hypersexuality initiated by Presley, pushing the invisible boundaries of a haughty conservatism bent against what rebellion they exuded. It’s a dynamic that seamlessly mirrors the state of modern hip-hop: much like the class of synth-infused, internet-savvy rap superstars that took the reins from a more lyrical pantheon, grievances about the Rolling Stones often banked on their songs being too celebratory of sex and drugs, the band being too mild-mannered, and true meaning being too difficult to extract from their thematic content. This stark contrast from the well-mannered orthodoxy of that period’s musical climate served to make them, in the eyes of many beyond their age group, the collective face of all things wrong with English society. In many ways, they grew to become public enemy number one – when Jagger and guitarist Keith Richards were arrested by British police forces on drug charges following a raid, they were given obscenely long sentences and interrogated on national television upon their release; they were referred to in a London Newspaper as “every mother’s nightmare”; in a nationally published poll following the aforementioned arrest, more than half of their native population voted that the sentences were not stiff enough.

“In all four cases, the artists in question made music that shifted the landscapes of their respective times, genres, and zeitgeists. At the same time, in the same exact four cases, no amount of creative prowess could grant one control over their reputation.”

But, beneath the layers of brash exterior they adorned themselves with both intentionally and unintentionally, there existed a lightheartedness that was reported on far less, a root benevolence that defined them on a personal level seldom seen by musical audiences. This was especially true for Jagger. Despite his frontman status making him the utmost embodiment of what onlookers grew to hate – with a smattering of negative magazine articles and newspaper clippings diligently constructing his reputation as Satan’s son – much like the events of the Altamont concert, his purity of heart was effectively overshadowed by the violent image that built its home around it. Being profiled by Esquire in 1968, ahead of the release of the Rolling Stones’ landmark album Beggars Banquet, a 26 year-old Jagger gave journalist Helen Lawrenson an anecdote about being turned away from a Wales pub, where although himself and Richards did not violate any immediate dress codes, the doorman took one look at them and vehemently turned them away. “It’s other people who cause the trouble,” he said. “They’re the ones that are rude and insulting. We don’t stare at them and start making remarks about how fat they are and how horrible they look. But it makes them furious, just the way we look.”

The outlook is one instance of a puzzling threat omnipresent, albeit silently so, in creative pathways: at a certain level, there comes the possibility that an artist’s ethos may eclipse even them. There is an indeterminable point in every creator’s career where influence and intent part, leaving consumers – both the supportive ones and the unsupportive ones – to make sense of the debris. Although it’s a ritual that defines legacies, it is entirely out of the hands of whoever’s legacy is actually up for definition. (“My mother always told me that as you go through life, no matter what you do, or how you do it, you leave a little footprint, and that’s your legacy,” Jan Brewer famously said. It helps to see the dynamic in this context: one may be able to leave a footprint, but simultaneously not be able to have a say in how people interpret it.) In the cases of figures like Marvin Gaye and Chuck Berry, the intersection of persona and creative output forged honorable apparitions in the gaps they left after they died, with fans and detractors alike collectively agreeing upon the narrative of positive influence. For other figures like Kanye West and (Steven Patrick) Morrissey, alternatively, the very same intersection is plagued by erratic public bearings, questions about reliability threatening to evolve into even bigger questions about long-term distinction. In all four cases, the artists in question made music that shifted the landscapes of their respective times, genres, and zeitgeists. At the same time, in the same exact four cases, no amount of creative prowess could grant one control over their reputation.

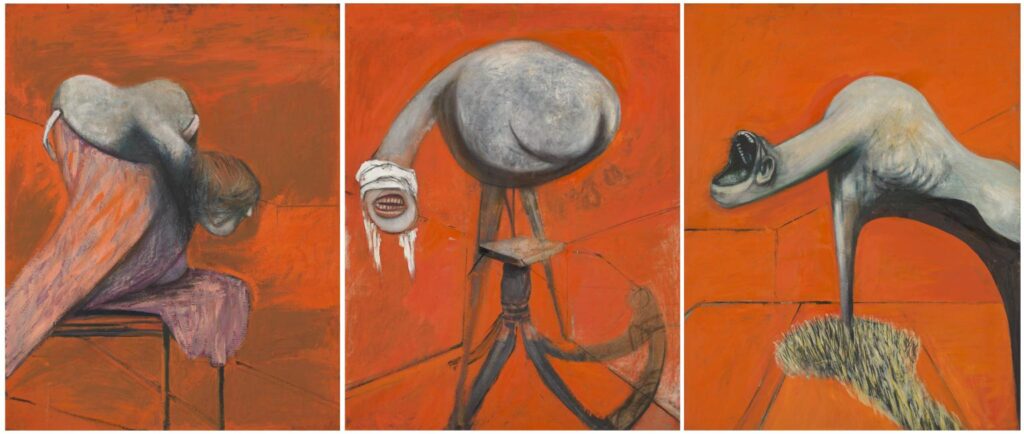

In a way that was emulative of the Rolling Stones’ duality, Francis Bacon, the famed 20th Century painter, was ultimately construed by the gloom-stemming themes represented in his work, even in spite of his contrastingly boisterous character. Bacon rose to prominence in the mid-1940s, with the widespread cultural impact of his Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion permanently etching his name into a then-growing list of revered English post-war documentarians. Commenting on the painting’s significance in 1971, the English art critic John Russell declared that “there was painting in England before the Three Studies, and painting after them, and no one … can confuse the two.”

A triptych, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion encapsulates the technical (Bacon had an affinity for separating his paintings into panels) and perceptive (he also had an affinity for making you feel a strange sense of depressed confusion) channels seated at the root of Bacon’s lasting reputation. In all three sections, there are figures that are ostensibly sentient; they are bent into mangled, inhumane contortions, their mouths stuck open in cries of agony, with rib cages, teeth, and jarringly elongated necks permeating a grotesque, unrecognizable plain.

Three Studies, though perhaps amongst the most jarring of them all, is only one of an expansive catalog – not including the hundreds he destroyed – brimming with equally unsettling works. His subjects ranged from screaming Popes, to bloodied floors, to disfigured human faces, all depicted with the same air of maddeningly indirect obscurity. You begin to feel like there is no way out of his world. “These things alter an artist whether for the good or the better or the worse,” Bacon once said of passion and despair. “It must alter him. The feelings of desperation and unhappiness are more useful to an artist than the feeling of contentment, because desperation and unhappiness stretch your whole sensibility.”

Even though Bacon’s work – like Altamont – ventured into the darkest crevices of human nature, Bacon himself was an aficionado of the opposite terrain, rather opting to spend his time frequenting bars and gambling with fellow seekers of the urbane. He was a bon vivant at heart, and reportedly did not get into painting until his mid-20s solely because he spent too long searching for subject matter that piqued his interest. In the days he spent flocking the social scenes of London’s Soho, friends Bacon attracted included, but were not limited to, Lucian Freud (although they fell out in the 1970s for unexplained reasons) John Deakin, Muriel Belcher, Henrietta Moraes, Daniel Farson, Tom Baker and Jeffrey Bernard.

This extroverted nature was not always the case, albeit, and its soft-spoken opposite manifested itself in two distinct periods preceding and following Bacon’s middle ages. From the onset, as a young man, it is commonly known that Bacon was shy and tended to both dress up, and act, in an effeminate manner, prompting verbal admonishments and physical beatings from his strict father. (In one anecdote that emerged in 1992, Bacon’s father had him repeatedly horsewhipped by their grooms.) Bacon often drew pictures of ladies with cloche hats and long cigarette holders; at one high-end fancy-dress party, he dressed as a Flapper – 20th Century women who wore short skirts and bobbed their hair to show disdain for accepted norms – some time after which he was kicked out of his family’s Straffan Lodge home upon being found admiring himself, in his mother’s underwear, in the mirror by his dad.

“They featured mangled figures dying agonizing deaths while sitting on the toilet, deformed, lifeless bodies oozing raw flesh from the confines of wooden chairs, and inconspicuous men sitting down in solitude, bewildered by the haze of their own confused company.”

Stemming even from beyond his ousting as a child, Bacon grew up with a sense of displacement that would stick with him over the course of his career at-large: for one, his family moved often, effectively bisecting his identity between his birthplace of Ireland and his longtime homeland of England. But perhaps to an even greater extent, there also existed the barrier of his sexuality. The ostracization he felt from his father, along with the constant movement of his family, led him to stumble upon a distinct niche in London’s homosexual underground, where, with a developed taste for swank food and wine being an immediate result, he found himself able to attract rich dates.

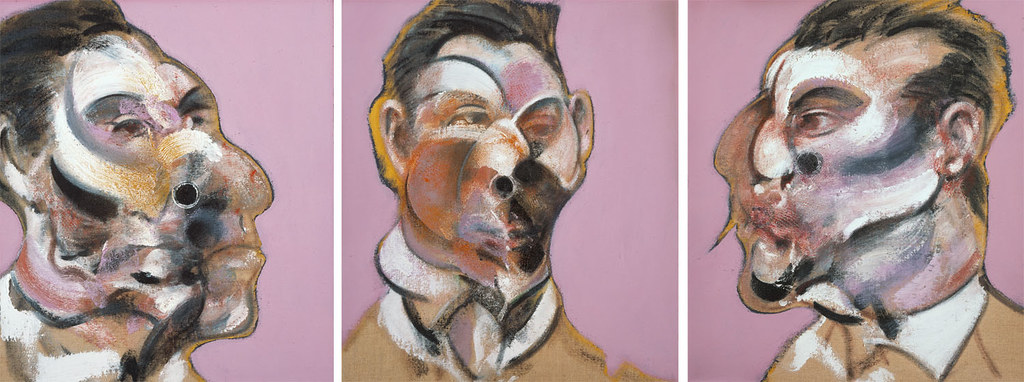

After several failed relationships with older, tumultuous men, Bacon met longtime romantic partner George Dyer at a pub in 1963. It was within this period – around the same time that a young Mick Jagger and co. were preparing to release their eponymous debut album (1964) – that, as Bacon’s social life began to thrive, his paintings began to dedicate themselves more noticeably to the splendor of humanity, rather than its morose downfalls. Dyer was the subject of many of these paintings. Bacon painted his lover with stark affection, harping on his brute physicality while concurrently reckoning it with a divine air of tenderness. “Our time together,” Bacon said to Dyer at one point, “has given me a whole new energy. Not just for the work, but moments like these.”

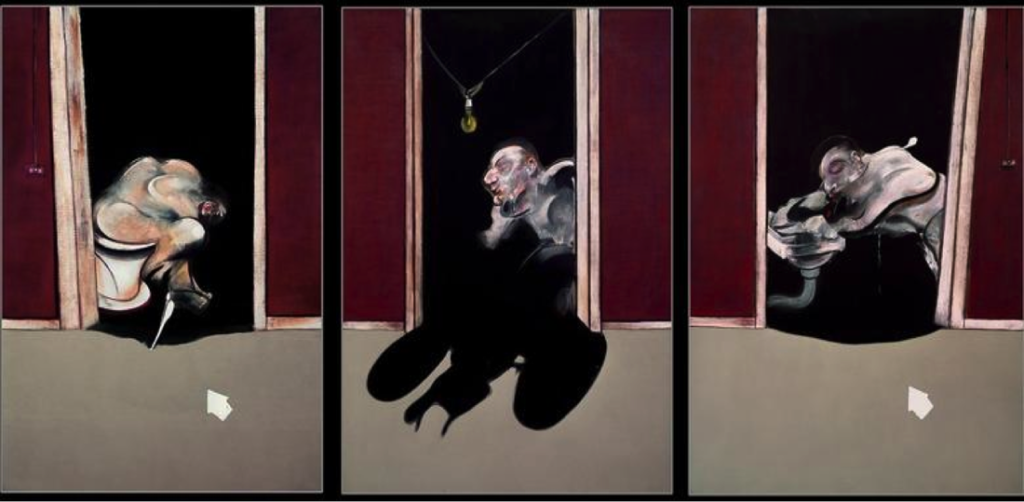

In 1971, though, eight years after they met and two years after the Altamont incident, Dyer committed suicide. The unexpected loss of what had been, at the time, Bacon’s closest companion to date, dispatched shockwaves that manifested themselves most immediately in his social life: he grew decidedly more detached from the illustrious cultural company he once kept, substituting large group relationships for one-on-one mentor-mentee connections that waned few and far between. The shockwaves also signaled a dramatic change in his art. During the period that saw Bacon at the peak of his social endeavors, he almost exclusively used his friends as the subjects of his paintings, with Dyer being his most frequent muse. Now, with a dramatically reduced caché of human stimuli to select from, Bacon doubled down on the study of human nature from the outside looking in, wounds still fresh, and morbidity still protrusive.

Bacon’s first paintings during this period were a series of three-panel works dubbed The Black Triptychs, made in memoriam of Dyer. They featured mangled figures dying agonizing deaths while sitting on the toilet, deformed, lifeless bodies oozing raw flesh from the confines of wooden chairs, and inconspicuous men sitting down in solitude, bewildered by the haze of their own confused company.

In Bacon’s own self-portraits, too, he depicted himself with holes in his neck, tire screech-esque obstructions blocking off large portions of his face, and unignorable deformities dominating all traces of human allure. It became distinct that his impetus to address humanity as a communicable, organic forum whose ebbs and flows were documented on the canvas, was impeded by a newfound conviction that the human race was rather something to be studied than engaged with. The titles of his works began to reflect this change in increasing frequency: Study of Reinhard Hassert; Study of Eddy Batache. Study for Head of Isabel Rawsthorne; Study for Head of George Dyer. Diptych 1982-1984: Study from the Human Body 1982-1984; Study of the Human Body – From a Drawing by Ingres 1982.

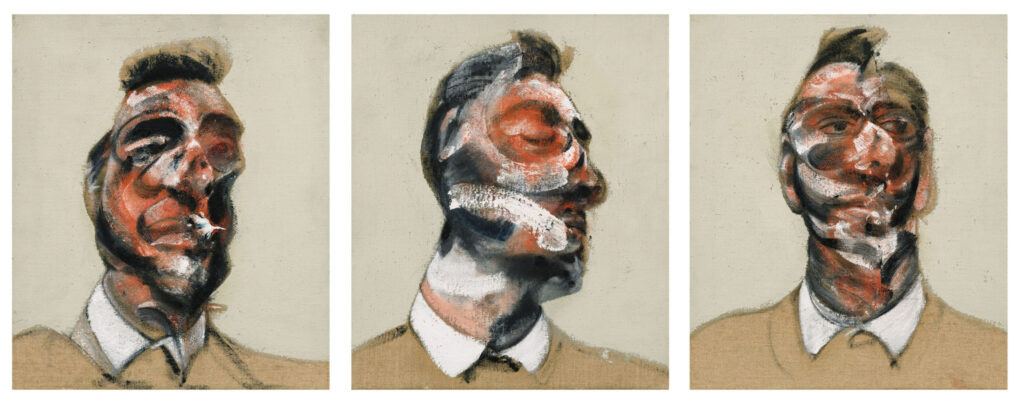

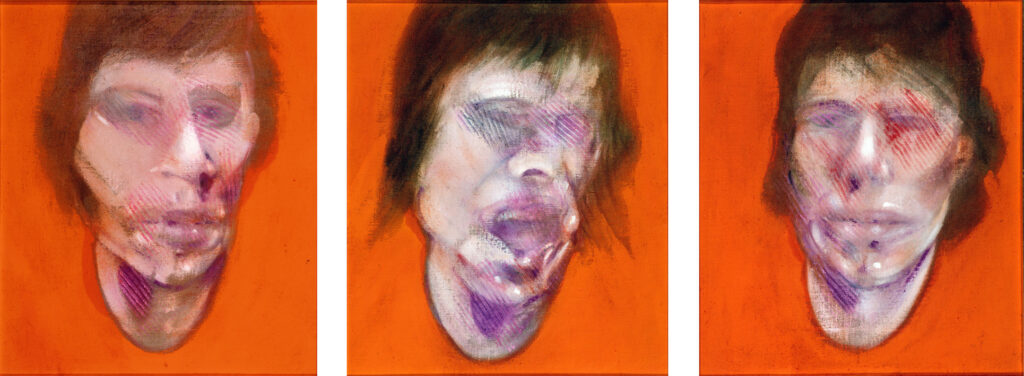

There is no evidence that Bacon ever saw the Rolling Stones on stage, but whichever of the two oft-told rumors is true, Bacon was approached at some point in 1982 by either Mick Jagger himself or a mutual friend. Jagger wanted a portrait. The result was Three Studies for a Portrait (Mick Jagger): one of, if not the only such portrait of Bacon’s that was not based upon someone he had a personal relationship with. With his typical subjects, Bacon tended to use a combination of built-up memory and photographic stimulation to reconstruct otherwise-forgettable facial features. In Jagger’s case, contrastingly, his globally televised androgynous allure, and widespread cultural omnipresence, served to usher him into a familiar air that conversation alone could not.

The triptych was a rare, jolting instance of Mick Jagger – the legendary future rock and roll hall of famer who everyone wanted to get a piece of – not being addressed up-front as the vibrant human being he was, but merely as an idea. A concept. A study. He was an experiment in the grander scheme of a much larger thesis surrounding humanity; whereas for the majority of his adult life he had been unanimously crowned the main character, he was suddenly a pawn on a chessboard grander than even him. The three iterations of Jagger’s face on Bacon’s study appeared just as taken aback as one would expect him to be by such news: one panel saw him boast a candid, blank stare; the center panel displayed him with his eyes closed and his mouth wide open, perhaps mid-scream; the rightmost painting pictured him staring dead into the eyes of the viewer, straight-faced and defiant.

No matter how far removed he was from his trademark spotlight, even so, the ever-so-slight flair of hot, seething, rage that quickly became his reputation – whether it was his intention or not – managed to shine through the cracks. “The beauty of the rock singer’s bone structure and the sensuality of his mouth are shown with love and care,” the British novelist and historian Andrew Sinclair remarked, “while only maroon stripes over the eyes suggest the fury and the force of his performance.”

The extraction of such furor from details as perceptibly minimal as maroon stripes in Bacon’s painting recalls once again, with eerie accuracy, the lack of complete control Mick Jagger ultimately had over how he was construed by the public. When Jagger was on stage, he was a sex-crazed animal who reveled in the hysteric energy generated by crowds who idolized him. (On some occasions, the maroon streaks of Bacon’s paintings proved literal: in one raucous performance, the crowd was so enamored with Jagger that an audience member threw a chair at his face, sending him to the hospital with a wound that required several stitches.) Because the stage was his primary public-facing frontier, toting an act as brash as his was, he had no option but to be polarizing. At the same time that teenagers around the world were ripping Rolling Stones records off shelves for one more hour-long sliver of his gruff intonation, high-end hotels were denying him entrance to the point of legal action being necessary for him to sleep at night. In 1969, when Beggars Banquet was released and the Stones had long cemented themselves as champions of England’s next cultural chapter, confirmation of their newfound megastardom came in the form of a biography, Our Own Story, set to be published in conjunction with author Pete Goodman the following year. Not even the milestone could protect them, and Jagger, from their cursed duality: when Goodman called the headmaster of Jagger and Richards’ childhood school in Dartford, England, for an interview, he responded “No comment. We don’t want the school connected with them,” and hung up.

For as much as we may know about where Mick Jagger’s heart truly lies, it remains very difficult to blame the headmaster. Which were the mid-Altamont Rolling Stones remembered for: the peace they sang of, or the bloodshed that erupted as they were singing of it?

One reply on “Mick Jagger x Francis Bacon”

Brilliant! This told the story of the two seemingly unrelated entities- how their stories brought them to a crossroads, and how their respective art portrayed them to the uncontrollable public opinion seamlessly. 10/10