Appropriation is built into Western culture, whether we admit it or not. The music of the Zambian Revolution is one often overlooked place wherein this is seen.

SAMUEL HYLAND

Who biographer Mark Wilkerson flawlessly encapsulates the origins of rock music in America and the United Kingdom in a 2006 publication: “Hard-nosed band(s) who reflected the feelings of thousands of pissed-off adolescents at the time.”

Rock, rather than mere music, is counterculture. It’s the ability to stick a middle finger up to an establishment that has failed you. It’s the evidence of frustration long kept inside. It’s a bunch of Hard-nosed bands who reflect the feelings of thousands of pissed-off adolescents.

What it isn’t, however, is exclusively American.

Acceptance of the latter is far too little.

If, by conceptual definition, rock boils down to anger, how could it possibly be that America and the U.K had more to be angry about than any other nation during the 20th Century? (looking at you, Berlin Conference of 1884).

Having just emerged from the second World War victorious, we seldom had anything to worry about besides how exactly our power would be applied.

We held most of the influence in the United Nations.

In several convenings between our leaders alone (and sometimes Joseph Stalin), we decided the fate of Europe in its entirety.

Yet, lo and behold, that “anguish” translated to fuzzed out guitars and bluesy lyricism – which isn’t problematic.

It only becomes an issue when it is used to discredit the deeper pain being felt abroad.

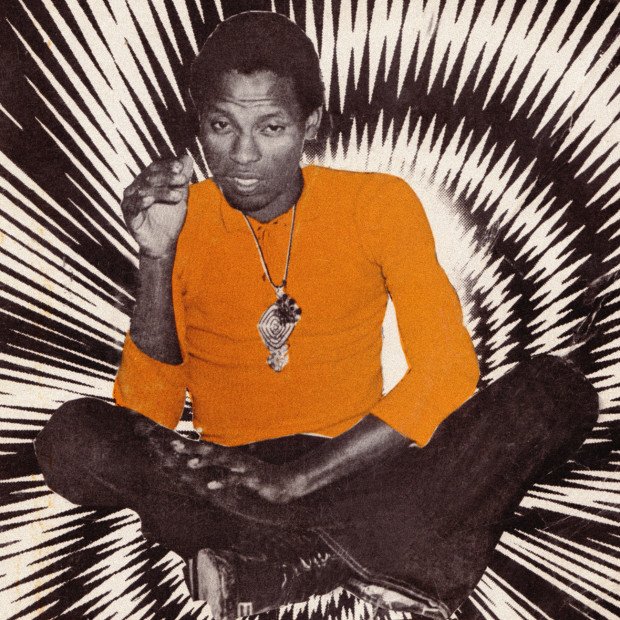

Being of African descent, I have tried to, over the years, somehow reconnect with the roots such assimilation may have led me to leave behind – and most recently, this has manifested itself in my clicking of a Spotify playlist entitled Afro-Psychedelica.

Simply put: I was ashamed at how shocked I was.

Of the two reactions, I’ll start off with the latter: “shock”. The element of surprise. At the outset, it came simply from the uncanny similarity that existed between what I was listening to and what is considered “Classic Rock.”

How so?

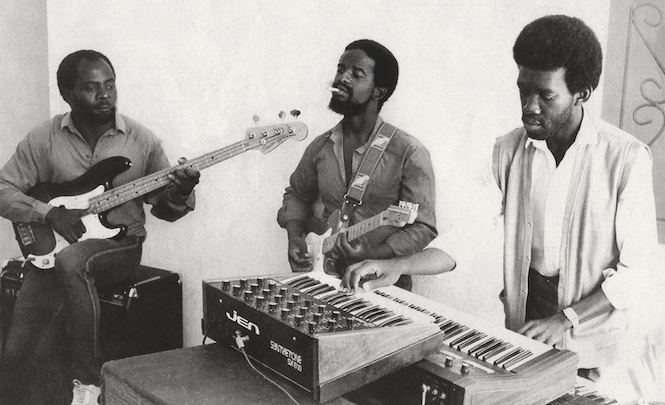

Pete Townshend wasn’t the only one playing power chords through Vox amplification.

Jimi Hendrix wasn’t the only one creating strange feedback via fuzz pedals.

And for some unknown reason, the firewall called the Atlantic Ocean was (and still is) what decided whether what I was hearing “deserved” to be glorified in my country the way its own music was.

Now, though, the shame.

It came about from one inescapable fact: I had been surprised in the first place.

Why was this shameful? It was shameful, because in simply being unknowledgeable, I was playing right into the western narrative popularized by Kipling’s “White Man’s Burden,” one that insinuates that Western culture is superior, and all people bearing dark skin cannot achieve selfhood without it.

Memories of when my uncle first played his ‘afrobeats’ for me as a child came back – as they often did – but this time, accompanied by my thought pattern at the time.

“They have guitars in Africa?,” I would think to myself then.

“It’s nice of the American band to play for the poor African people.”

“Why do they sound so good if they can’t afford equipment?”

Most of the music that populated the playlist came as a product of the Zambian Revolution, which granted the people of Zambia independence from British oppression.

The saddest part: even in their freedom, they were still bound ideologically to their former captors – so much so that I could be profoundly shocked at Zambian music sounding remotely similar to that of Great Britain and the United States.

I reached out to Natalie Zwerger, director of New York University’s Center for Strategic Solutions, for her take on the matter.

“Appropriation is a real thing,” she told me via email. “I think African music has in turn influenced African American music and Black music generally, and white and latinx artists in this country have appropriated those influences as their own.”

She continued: “Ultimately, in a racist, capitalistic society, this serves the dominant culture and is exacerbated by all of the pernicious myths which serve to diminish the roots of African music and demean people of the African diaspora in general.”

I additionally asked Ms. Zwerger what she thought contributed to the unfounded linking of Africa to the idea of poverty.

“I think folx just don’t know much about the diaspora,” she answered. “The history they are taught begins at the point that Africans were enslaved, murdered on a genocidal scale, colonized, and forced from their homelands. That is not a full history of a people.”

“The history they are taught begins at the point that Africans were enslaved, murdered on a genocidal scale, colonized, and forced from their homelands.”

“That is not a full history of a people.”

– Natalie Zwerger

The child, as put by late philosopher Acharya Rajneesh, embodies “the freshness of consciousness, which never becomes old, which always remains young.” With the freshness of my elementary-school consciousness, I had heard the rich music of Africa, and automatically concluded that it was American.

That says a great deal about the society we live in.

Western culture, since (and perhaps even before) the dawn of imperialism, has bathed itself in the idea of superiority in all disciplines, fields, and mediums; any regard for what that may mean abroad has been tossed out of the window centuries ago.

And music isn’t the only thing that this applies to.

For example, at a recent birthday party for my then-eight-year-old cousin, I intended to throw away the crusts of two pizza slices I had just guzzled down. I waited for the garbage bin behind a peer of my cousin’s, a quiet young boy who shared my complexion.

“People are starving in Africa,” he told me as the crusts slid off of my plate.

The only narrative of my homeland broadcast in the United States is one of nothingness. Neediness. Poverty.

By transitive relation, the only narrative of me broadcast in the United States is one of nothingness. Neediness. Poverty.

Neither are accurate.

But, for as long as the West seeks to feed its desire for supremacy – at the expense of not only the diaspora, but the truth – any American mirror I look into will display the man Kipling calls me to be, and not the man I am.