The Exploding Plastic Inevitable: Andy Warhol’s Short-Lived Rock n’ Roll Experiment

With Warhol and his executive touch, The Velvet Underground became an epic concoction of mankind and the study of it; art and rock & roll; the paintbrush and the electric guitar; visual and auditory abstraction.

SAMUEL HYLAND

“Warhol’s brutal assemblage – non-stop horror show,” Michaelo Williams of the Chicago Daily News wrote of the Velvet Underground upon their 1966 emergence. Not long prior, Williams had viewed one of several showings attached to “The Exploding Plastic Inevitable” – a grotesque, strategically curated series of performances put together by Andy Warhol to garner exposure for the fledgling band surrounding their debut release. “He has indeed put together a total environment, but it is an assemblage that actually vibrates with menace, cynicism, and perversion. To experience it is to be brutalized, helpless- you’re in any kind of horror you want to imagine, from police state to mad house. Eventually the reverberations in your ears stop. But what do you do with what you still hear in your brain?”

The reverberations left by The Velvet Underground & Nico (1966) were – and currently remain – just as much immediately auricular as they were permanently cultural. TVU&N is often declared pioneer of the ‘art rock’ subgenre; and, such labeling was an acute reflection of chasmal shifts having taken effect in the primitive realm of art itself. At the onset: art, much like music, was exclusively a religious medium before it began to take on whatever form it pleased. Both within and well after physical art’s medieval-era rise to prominence, artistic quality was determined by how well any piece fit the gauge of skillful intricacy – that skillful intricacy, too, being in mere existence fundamentally bound to the world of Christian divinity. It was the European Renaissance of the 15th and 16th Centuries, albeit, that saw society en masse challenge the form’s surrounding status quo by seeking to infiltrate devout religion with organic secularism. This was, of course, to the conservative standpoint’s dismay (as we know, many adjacent ‘renaissance thinkers’ were made subject either to excommunication from, or execution by, the Catholic Church), but who, now, was to say that art was prohibited from beyond cathedral walls? Whether you liked it or not, one had to admit that the answer was no one.

“The movies make emotions look so strong and real, whereas when things really do happen to you, it’s like watching television—you don’t feel anything.”

The artistic infrastructure of 20th Century New York served to articulate such a construct on a micro scale. Whereas throughout the European movement the conservative element was Catholicism, now, the oppressor was a matter of form – the aforementioned skillful intricacy, now removed from any religious stranglehold. Often cited as a stark depiction of such an infrastructure, in the year 1917, the Society of Independent Artists sought to hold its inaugural exhibition at New York’s now-repurposed Grand Central Palace hall. The French-born multidisciplinary artist Marcel Duchamp submitted a porcelain urinal, unaltered save for “R. Mutt” scribbled in black Sharpie on its exterior. The association was not allowed to turn away works from contributors who paid the fee. Duchamp’s Fountain was accepted – but on top of it never being displayed in the gallery, he was never refunded.

Similarly, when an increasingly abstract-expressionist New York began to overtake Paris as Earth’s artistic epicenter in the 1940s, initial windows of opportunity for the movement’s premiere creators were firmly shut. Jackson Pollock, for instance, did not sell a single one of his now-famed “black pourings” upon exhibiting them at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1951. Nine Years earlier, too, Mark Rothko was so stirred up by a scathing New York Times review of his work, that he wrote an intricate-yet-futile justification of it in letter form to the publication’s art editor. “What painting lacks today is what bad painting always lacks: adequate intellectual capacity and manual skill,” the late New York City art and dance connoisseur Lincoln Kirstein said of such emerging practices in The State of Modern Painting (1948). “Experiments are passed off as fully achieved and mature art.”

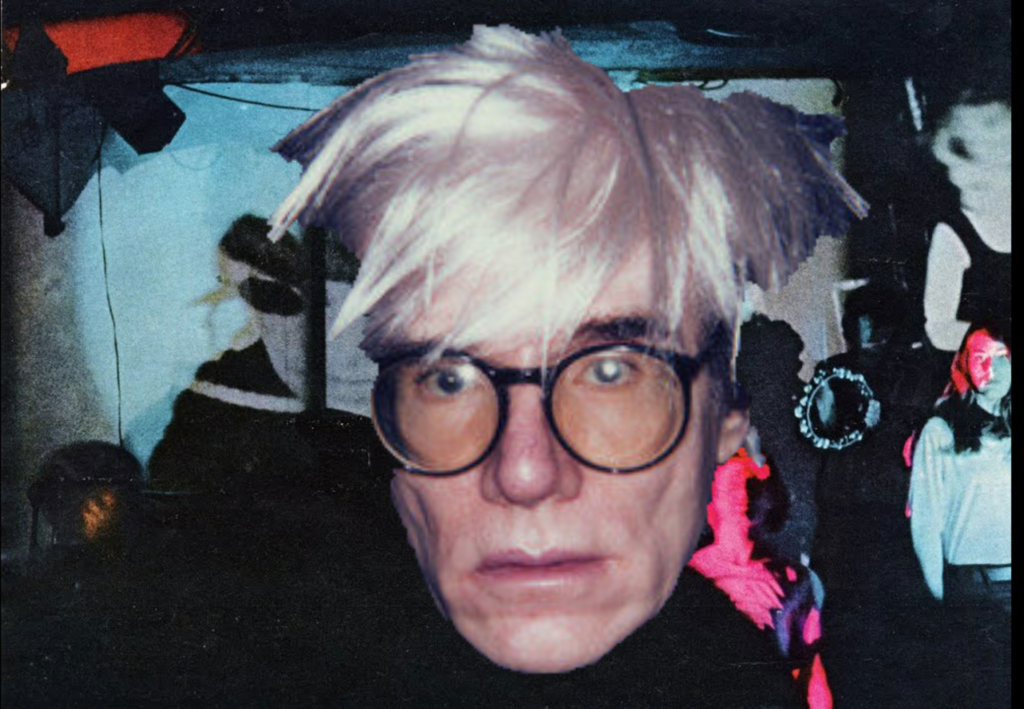

The crux of Andy Warhol was to take the consumerism that comprised Abstract Expressionism’s roots, and extract from it a class of satire that effectively reversed scrutiny from composer to spectator. By all definitions, Warhol was a mad scientist. He worked exclusively out of a Midtown apartment of his dubbed ”The Factory” (in which he created movies, paintings, time capsules and psychosexual dramas with intellectuals, drag queens, playwrights, Bohemian street people, Hollywood celebrities, and wealthy patrons alike); he adopted a deliberately selected clique of amateur personalities – “Warhol Superstars” – who both appeared in his work and accompanied him in his social life; he coined the expression “fifteen minutes of fame” with the epitomization of, through his posse, his own dictum that “in the future, everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes.”

Artistically even, Warhol’s impact lived enveloped within an output that, once again, served as a mirror to the consumer rather than a spectacle. Empire for example, a film of his released in 1968, featured no characters, plot, nor change of setting. All eight hours and five minutes of tape were occupied by unmoving slow motion footage of the Empire State Building – the purpose of which was declared by Warhol himself as “to see time go by.” Time is agreed upon by many to stand as man’s most prescient adversary. To force viewers to come face-to-face with the very construct that guaranteed their eventual expiration, was to prompt internal dialogue through a conversely external display: the conceptual textbook ‘work of art’, although chiefly heralded for extrinsic discourse up to then, was now conspicuously shifting its likeness, turning the scrutiny inward. Among an extensive list of similarly audacious films were Eat, a nearly 45-minute display of a painter eating a mushroom, Taylor Mead’s Ass, 76 minutes of the titular actor shaking just that, and Sleep, five hours of footage documenting Warhol’s sleeping boyfriend. In 2004, forty years after its initial release, Empire was selected for preservation in the National Library of Congress.

The reverse formula was well in action, too, with painted work. A vast majority of Warhol’s physical art was primarily targeted toward introspection through the display of consumer-oriented cultural entities – His most popular works involve multicolored repetitions of Marilyn Monroe’s face; painted cans of all (up to that point) 32 Campbell’s Soup flavors populate the canvas of a premiere piece of his on display at the Museum of Modern Art (Campbell’s Soup cans were a go-to for Warhol – he also produced a women’s dress born out of the latter design); and, reconfigurations of celebrity faces and bodies alike, from Michael Jackson, to Prince, to Elvis Presley make up an expansive portion of his complete collection.

Andy Warhol was a people person, but not as much socially, though that element was abundant, as studiously. His works saw humanity as something to be studied before it was something to be interacted with – and a growing cult of celebrity amidst the 20th Century provided the perfect lens through which any such theme could be delved into. The aforementioned Marilyn Monroe artwork, Marilyn Diptych (1962) came shortly after the title model’s fatal drug overdose occurred within the same year. Monroe had forefronted much of mainstream culture across mediums up to the accident, and her death rattled Warhol as much as it rattled the country. On the left side of the painting’s canvas, one sees a five-by-five grid boasting well-saturated, lively, vibrant depictions of her face. On the right side, all color is sucked away by monochrome. Whereas the left grid saw boxes of her face relatively unchanged, there are points where dark splotches overtake her smile, some appearing as slight black marks on a bad photocopy, and others rendering her likeness completely undetectable. In the five images that make up the right side’s final column, Monroe – much like all the temporary glories of consumerism, Hollywood, and material humanity eventually do – has faded away.

Warhol’s art was intrinsic enough to the human mind that, oftentimes, it drove it to insanity. On June 3, 1968, as Warhol rode the elevator in his “Factory” apartment-slash-studio alongside associate Mario Amaya, radical feminist writer Valerie Solanas shot both men in a premeditated murder attempt. In her lone rationale delivered to law enforcement immediately after the incident, she told cops that Warhol had “too much control over my life.” In her only connection with Warhol before then, Amaya had been turned away from his studio following a dispute concerning a misplaced film script.

“Before I was shot, I always thought that I was more half-there than all-there—I always suspected that I was watching TV instead of living life,” Warhol said of the incident later on. “People sometimes say that the way things happen in movies is unreal, but actually it’s the way things happen in life that’s unreal. The movies make emotions look so strong and real, whereas when things really do happen to you, it’s like watching television—you don’t feel anything. Right when I was being shot and ever since, I knew that I was watching television. The channels switch, but it’s all television.”

“The point made by the sensation is one that only Warhol himself could have conceptualized: you yourself are the impending doom. The music is not a spectacle. It is a mirror. And when you glare at it long enough for the fog to clear, the version of yourself that stares back at you is a life-sized concoction of your dread’s lone foundation.”To see life as a television program is to exist outside of it. With both Warhol, and the initial European Renaissance he reimagined, the boundaries of art were expanded to an extent at which all things seeming to take on the form of such resistance were dubbed “art” more generally than the conservative predecessor. (Hence, “art rock”. All rock is art, but the prefix served to say especially the avant-garde stuff). Living life from in front of the television screen rather than inside of it allowed Warhol to not only crystallize such a distinction, but ultimately reshape a once-stubborn infrastructure into one that devoutly observed it.

Sometime in December of 1965, while lounging at Cafe Bizarre, a New York club revered among tourists for its unconventional food and drink offerings, Warhol came across a local band dubbed the ‘Velvet Underground’. The intersection was not the coincidence it appeared to be, but a strategically calculated rendezvous – Paul Morrissey, a film director who worked closely with Warhol, had convinced him to dismiss negative preconceptions and give rock music a long-awaited chance. “Andy didn’t want to get into rock and roll; I wanted to get into rock and roll to make money,” Morrissey recounted. “Andy didn’t want to do it, he never would have thought of it. Even after I thought of it, I had to bludgeon him into doing it. My idea was that there could be a lot of money managing a rock and roll group that got its name in the papers, and that was the one thing Andy was good for – getting his name in the papers.” Morrissey spoke extensively with both parties before they crossed paths. Some time prior to Warhol doing so himself, he saw the band perform at Cafe Bizarre, conversing backstage post-performance to acquaint them with the idea of being managed by New York City’s most prolific artist. With Warhol, the primary selling point was getting his underground films to somehow merge with what was now an increasingly polarizing musical culture.

What struck Andy Warhol most forcefully about the band was that they seemed to be doing, through music, exactly what he sought to do with his art. With a lineup consisting of frontman Lou Reed (vocals and guitar), Sterling Morrison (bass guitar and backing vocals), and Angus Maclise (percussion), they boasted an unapologetic counter to a mainstream long dominant, themes of lustful, drug-infused madness sharply contrasting a nationwide advocacy for peace amidst raging political violence. The Velvet Underground emerged within an era that saw groups like the Beatles, Love, and the Beach Boys sell records packed with either warmly presented sounds, warmly presented lyrical content, or a combination of both. In stark disparity, in two of the Velvet Underground’s most commonly performed live songs prior to their studio debut, they sang about a man’s crippling diacetylmorphine addiction, and the pleasures of sadism and masochism. Much like struggles faced by original Renaissance painters and figures surrounding the Abstract Expressionist Movement, such diversion from what was commonplace did not amount to immediate success; but, an overall careless attitude – in the Velvet Underground’s case, more snobby than courageous – was the difference between sweeping obsoletion and any one shot at once-in-a-generation significance.

Warhol was the sole factor that made society entertain their dynamic. In a move that actualized the advice given to him by Morrisey, he organized the aforementioned “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” tour as a deliberate crossing of rock & roll with his underground filmography – two arguably completely opposite mediums – in which the band would perform chaotic avant-garde sets on stages lit by vivid projections of films directed by their manager.

At the debut performance, as recounted by Ara Osterweil in her book Women’s Experimental Cinema: Critical Frameworks, the then-25-year-old experimental filmmaker Barbara Rubin “hurled derogatory questions at the esteemed members of the medical profession (present in the audience), including: ‘What does her vagina feel like? Is his penis big enough? Do you eat her out?’” whilst casting blinding lights into the crowd. Even after the display, when regulations were put in place to attract more civil audience members, spectators resorted to violence at the sound of the band alone. “There we are, doing six sets a night at this terrible tourist trap in the Village,” Reed said in retrospect. “The audience was attacking people over the music.” There is a scene in the ABC sitcom The Goldbergs in which Erica Goldberg, then a college freshman in way over her head in her school’s local art scene, is horrified by a posh avant-garde showcase. One can picture this imagery being the ultimate substance of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable: you came to please your sensory organs; you left with all of them bleeding.

This was no ideal way to launch an up-and-coming band of inner-city kids into pop culture prominence. But Andy Warhol held power over the scene that the Velvet Underground did not. It was Warhol’s ethos that convinced Verve Records to sign the group ahead of their first release. And, in preparation for the album itself, it was Warhol who took the reins of executive decision-maker: his first act as their new manager, besides organizing the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, was – much to the original members’ dismay – to push for the inclusion of Nico, a German pop singer-slash-model who had just met him a week prior. Although tensions between the band and its newest member ran early recording sections (which, it’s worth mentioning, were held in the ‘Factory’) into the ground, after Warhol offered them new instruments, free rehearsal space, food, drinks, and drugs in exchange for letting Nico sing lead on certain tracks, the blueprint for musical output was set in stone.

With Warhol and his executive touch, The Velvet Underground became an epic concoction of mankind and the study of it; art and rock & roll; the paintbrush and the electric guitar; visual and auditory abstraction. But especially in an era more and more acclimated to a mainstream of folk-adjacent romanticisms dominating airwaves, 1966’s The Velvet Underground & Nico was just what Michaelo Williams said its promotional tour was: Warhol’s brutal assemblage – non-stop horror show.

When I first listened to the album, I had just gotten wind of my mother and sister having left to go on an errand run – meaning that, save for my dad (who was wearing headphones in the living room), I had the house more or less all to myself. The inner sleeve of my 50th anniversary vinyl copy was adorned with critics’ takes on the Exploding Plastic Inevitable.

One described it as a “Three-ring psychosis that assaults the senses with the sights and sounds of the total environment syndrome . . . Discordant music, throbbing cadences, pulsating tempo.”

“Not since the Titanic ran into that iceberg has there been such a collision as when Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable burst upon the audiences at the Trip Tuesday,” another wrote. “The Velvet Underground is so far out that it makes the tremendous thumping beat of the great, groovy group which opened the program sound passé.”

Of course, sixty-three years after the album’s release, it was fairly easy to – as I did – look at such musings as overstatements, given the far more vast expanse of modern music that has long crossed whatever the line was in 1967. But upon dropping the needle, one becomes immersed in a squalid prison tailored to whatever it is that they fear, inescapable until the final track fades to silence.

Sunday Morning, the album’s first number, opens with a hauntingly innocent assemblage of noises reminiscent of a newborn’s wind-up toy. With a voice that drawls out into a lingering echo, Reed – just like Warhol did with Empire – throws the passage of time into permanent reverberation within the mind, warbling ever-so-casually about wasted years and a lost world never to be regained again. Femme Fatale, moreover, the first song on the record led by Nico, features an instrumental section that registers as purgatory’s eternal elevator ambience, the singer herself eerily serenading infamously reckless Warhol Superstar Edie Sedgwick. At the conclusion of a downward spiral that ruptured the final years of her life, Sedgwick overdosed on prescription medications and died at 28 years of age. Nico’s vocals are spine-chillingly monotone: lyrically, they eulogize Sedgwick as the heartbreaker she was in life – but on the audible plane, only death and heartbreak are left to be discerned.

At the genesis of Side B, Heroin plays as a somber love song to a substance Reed appears to know very well will kill him – in its beginning, it makes him “feel just like Jesus’ son”; by the end, he’s thanking God that he’s “good as dead.” By the time The Black Angel’s Death Song fades in, the final ten minutes of the record are an increasingly confused compound of chaotic horn assemblages, guitars that perform as violently wrecking locomotives; chaos that seems to be leading toward an impending doom. Yet – where the impending doom should manifest itself, there is silence. I finished the record paranoid, though the instigator of my fear had long faded out: eventually the reverberations in your ears stop. But what do you do with what you still hear in your brain? The point made by the sensation is one that only Warhol himself could have conceptualized: you yourself are the impending doom. The music is not a spectacle. It is a mirror. And when you glare at it long enough for the fog to clear, the version of yourself that stares back at you is a life-sized concoction of your dread’s lone foundation.

Although today it is heralded as the lone pivot-point of rock music from single entity to artistic medium, The Velvet Underground & Nico was marked by an abysmal commercial performance, with negative reviews offered by the few publications that chose to regard it at all. After growing frustrated with Warhol, Reed fired him soon after the album’s release, getting rid of Nico as well.

But for the brief period that it lasted, the Velvet Underground’s crossing with Andy Warhol was an unthinkable, repugnant, violent, distressing, experimental foray into the human mind by one of the human mind’s premiere scholars. Over five decades later, nothing has changed: whether you liked the music or not, you will have spent forty-eight minutes staring into your own eyes. And if five decades’ worth of prominence have proven anything, it’s that the introspection far outlasts the music.