🌐 🌐 🌐

The Opaque Iconoclasm of Lizzy Mercier Descloux

SAMUEL HYLAND

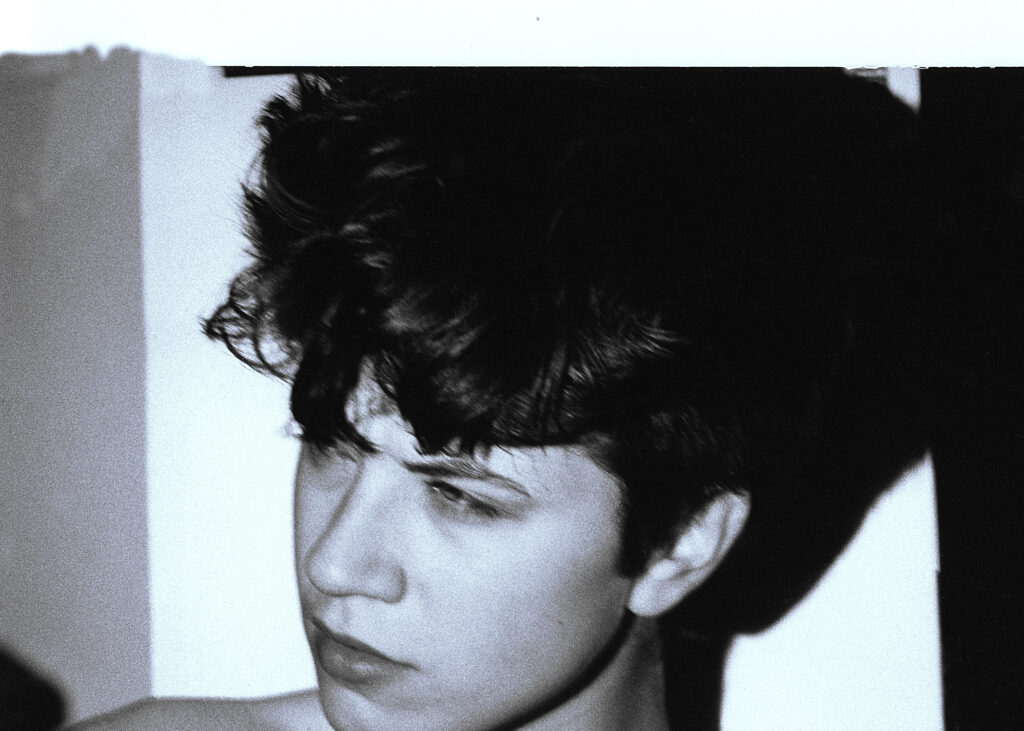

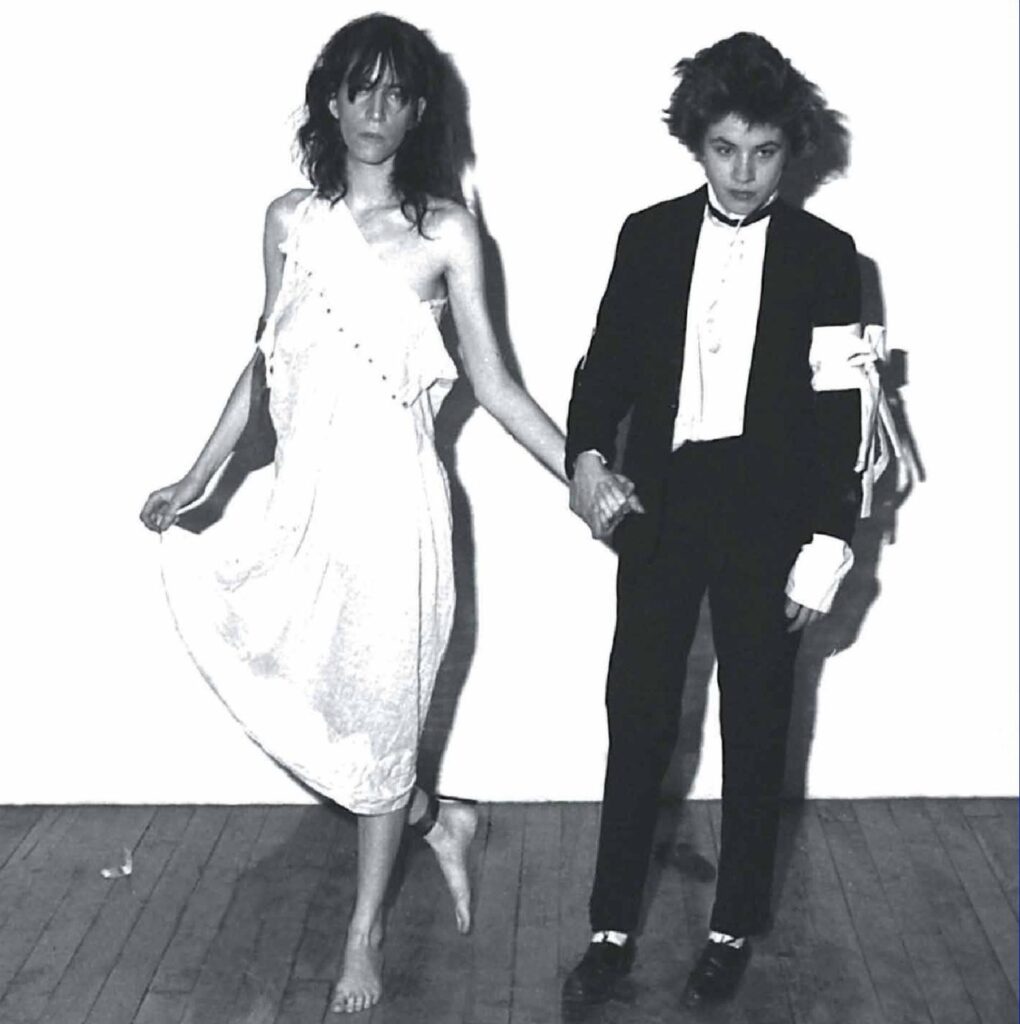

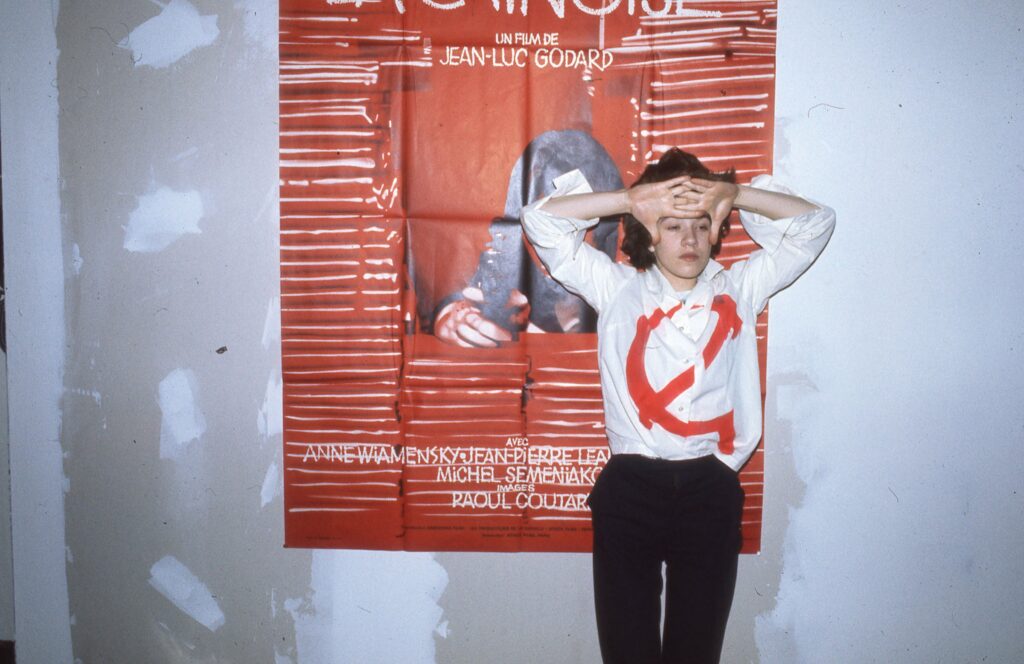

One of the most famous photographs of Lizzy Mercier-Descloux portrays her standing next to New York City punk icon Patti Smith, impersonating the French poet Arthur Rimbaud in a clunky two-piece menswear suit with a white ribbon draped onto her right shoulder. Her face is downcast in a way that purports itself to be sarcastically aloof; she grasps the hands of Smith – who, impersonating Rimbaud’s sister Isabelle, is a skeletal, menacing figure with bony limbs protruding from a white dress – near the pair’s shared midsection. Smith and Mercier-Descloux took a grandiose sum of photographs that day, each one adding a disparate layer to the seemingly straightforward theme of deceased poet dress-up. Another image sees Mercier-Descloux seductively lift the hem of Smith’s skirt so that it reveals the middle of her bare thigh, while Smith, pseudo-crucifixion style, raises a flailing arm in the direction of a hammer-and-sickle flag positioned a foot or so to the right. Yet another sees the pair wrapped in a tight embrace, with Smith holding Mercier-Descloux around the neck, like lovers just as in awe of each other as they are disillusioned with the remainder of the Western world. One more showcases Mercier-Descloux alone, disheveled as if having just stumbled out of the bedroom of a one-night romantic partner, her fierce eyes being two of few things about her that seem to be in any form of control.

Images from this specific photoshoot populate the vast majority of results in a Google Images search for Lizzy Mercier-Descloux – pessimistically speaking, because not very many high-quality images of the singer exist – but on a coincidentally brighter note, because they encapsulate uncannily well the unrestricted distinction she burgeoned in her short time as a prominent figure: she was free-spirited enough to trespass artistic boundaries, yes, but she was also resolute enough to let those unpalatable idiosyncrasies represent her in public perception. (The image that featured her standing alone was, years after it was captured, used as the cover art for a single). If the zeitgeist was an Americanized cultural relapse, Lizzy Mercier-Descloux was, quite literally, a suited cosplayer of deceased French odists with a USSR banner on her bedroom wall.

To say that Mercier-Descloux was a firebrand iconoclast would be a disservice in the sense that such a statement insinuates deliberate intent. Lizzy Mercier-Descloux was an iconoclast – not because she strategically said no to the things everyone else was saying yes to, but because she was too eclectic to possibly fit as neatly into most cultural frameworks as superstardom then demanded. As put forth by her legendary surname, Mercier-Descloux was born in Paris, France, after which she spent a majority of her adolescence living under the roof of her aunt, a lesser-revered local, and her uncle, a known flocker of late-night boules games who worked mornings in the Renault Factory (a car manufacturer in France). One day in the spring of 1975, Michel Esteban, a 21 year-old music aficionado who had just opened a rock merchandising operation across the street at 12 Rue des Halles, spotted Mercier-Descloux, then 19 years of age, on the balcony of her home. He fell in love, and left a note on her bicycle. Mercier-Descloux followed the note’s invitation, venturing out to visit Esteban’s shop on several occasions. She was a disenchanted student at L’Ecole des Beaux Arts, a prized French grande école that matched its reputation with rigor – amid intensifying disillusionment, Esteban’s romantic interest was a perfectly-timed rationale to drop out; think of it not as the last straw on the camel’s back, but perhaps the closeby jug of ice-cold water tempting the camel to disobey his master’s pull once and for all. Mercier-Descloux and Esteban’s romantic involvement was, once the former abandoned her education, bolstered primarily by a shared affinity for music that crossed geographical borders. They moved in together at Esteban’s residence and began looking more and more outward for satisfaction of their cultural appetites – a year before he met Mercier-Descloux, Esteban’s shop brought in enough money to fund a trip to the United States (where he befriended Patti Smith, Television, and the Ramones); and a year after, the two started taking international reporting trips for a self-produced music magazine entitled Rock News. “I knew something was really happening there,” Esteban told Pitchfork’s print quarterly, The Pitchfork Review, in 2016. “Nobody was saying anything in the French press, so I thought, why not make a magazine?”

“Very often now when a woman plays guitar they really try to be equal to men, so they’re just gonna practice so they sound like Jimmy Page. I think women have a certain sensibility that could make them approach guitar in a very, very different way, in a beautiful way.”

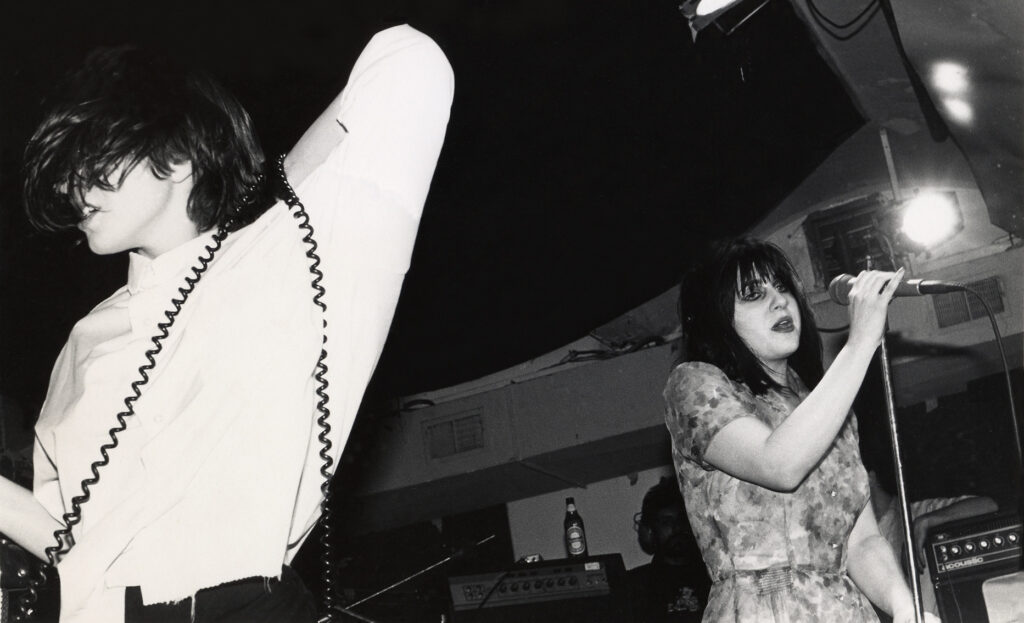

Rock News became the vehicle through which Mercier-Descloux would be entered into a Western world she had spent her entire life admiring from afar – exposing her to friendships and professional correspondences with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Chet Baker (who played some of his last ever recorded trumpet notes on Mercier-Descloux’s penultimate album One for the Soul [1985]), and, of course, Smith. More importantly, yet, New York City was also the place where she and Esteban founded their joint label ZE Records in 1977, not long after which they broke up and promised to remain related on strictly professional terms. (Just a year before, they had arranged for legendary record producer Kim Fowley to do an interview with the Runaways for Rock News – but, in a move that poetically captured their impulsive youthfulness at the time, wound up abruptly declaring punk to be dead and therefore shutting down the publication.) ZE was founded on the ideals of the freewheeling New York D-I-Y culture it arrived on the heels of, where no lack of experience could withhold any act from a piece of the burgeoning pie. One of ZE Records’ first signees was Rosa Yemen – the namesakes of which were, respectively, Rosa Luxembourg and the Baader Meinhof group – a duo founded by Mercier-Descloux and Didier Esteban, her ex-boyfriend’s brother. Much of the idea came with Patti Smith’s encouragement. In an article published on Medium, (Michel) Esteban told journalist David Chiu that Smith was “very fond of Lizzy. She said, ‘Come on, you should make a band, you got a great look.’ It was the punk times(,) so everybody could make a band even if you didn’t know how to play any instruments.”

In the most offenseless way possible, Rosa Yemen didn’t sound like they knew how to play their instruments, much to Esteban’s point. They did not record much, which is often true of impulsively-created avant-garde bands having flocked New York’s backstreets in the 70s and 80s, but in the little that they did put on wax, their intentions were as unclear as the substance itself was uninviting. There is no clear-cut entry point to hearing Lizzy Mercier-Descloux belt haunting threats in fluent French over dramatically amateur guitar strums and intense background screams on “Rosa Vertov,” the opener of their 1980 eponymous (and only) EP, just as much as there is nothing that can prepare one for the fuzzed-out, pseudo-Velvet Underground & Nico sonic disorientation that is “Larousse Baron Bic,” its fourth track. The sounds are confusing and unwelcoming, seemingly created not for human consumption, but for human experimentation – the object of the experiment being tolerance, far before anything remotely musical can ever come into the equation.

But, then again, it wasn’t like Lizzy Mercier-Desloux and Rosa Yemen were trying to come off as if they knew how to make music come out of their instruments in the first place. Mercier-Desloux was no virtuoso, but with the asymptote of perfection invigorating many of the upstart female rock stars that surrounded her (this is the same exact New York City infrastructure that birthed Debbie Harry and Blondie), she opted, rather, to exist outside of the graph and use music as a means to inadvertently spite its constituents. She had just acquired a Fender Jazzmaster no more than a year before she began releasing content through a professional label. Palatability was not as stringent an endgame for her as was output. “Very often now when a woman plays guitar they really try to be equal to men, so they’re just gonna practice so they sound like Jimmy Page,” she told the now-defunct New York-based magazine Creem in one interview. “I think women have a certain sensibility that could make them approach guitar in a very, very different way, in a beautiful way.”

In order to take Mercier-Descloux’s statement at face value as a gauge for her own music, one must first be a believer in the idea that beauty is subjective. Lizzy Mercier-Descloux, by many standards, was not a representative of the beauty glorified by what Western culture she now found herself enveloped in: her voice, which would eventually all-but-succumb to decades of persistent chain smoking, was an aggressive growl that sometimes literally scared would-be collaborators away. Her face, emblazoned most jarringly with a long, protrudent nose that somehow made her eyes look even angrier, was constantly undergoing radical aesthetical changes, each one even more intensely bizarre than the last. In contrast to the slick sundresses the models, and therefore cultural ambassadors, donned on fashion magazine covers geared towards her demographic, she spent her free time dressing up as deceased French poets underneath the roofs of Soho lofts adorned with communist paraphernalia.

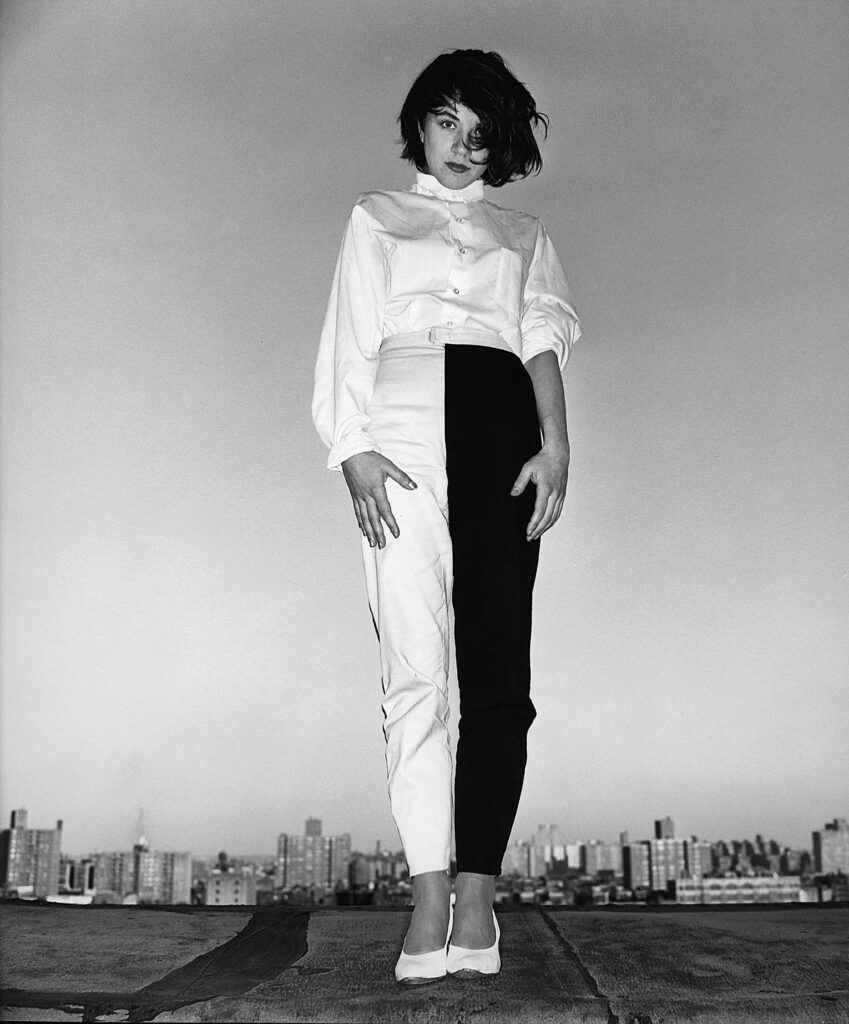

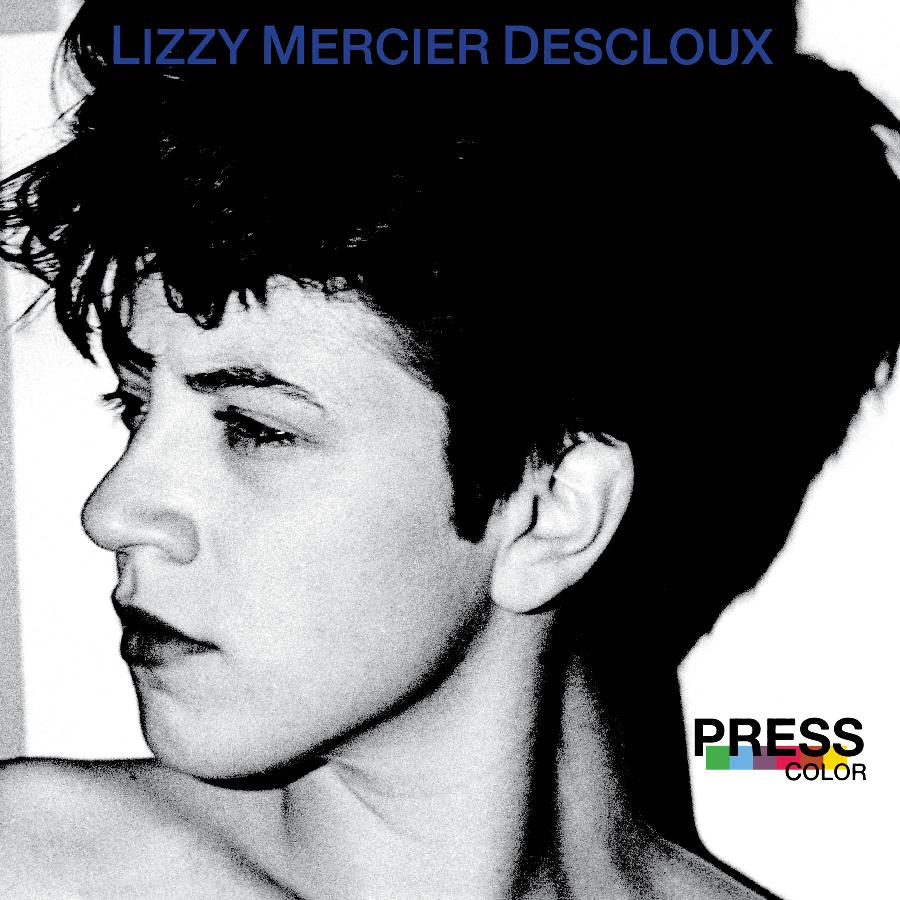

Her first solo album for ZE Records, Press Color, was recorded throughout 1979 in New York City and released later that year. Bedecking the cover is a candid black-and-white photograph of Mercier-Descloux’s face, inquisitively looking off to a corner with skeptical eyes and a disheveled, shortly-cut bobbed hairdo. It’s an uncanny warning for the equally disaffected music it advertises – enjoy the music, one feels, and you get to triumphantly say that you “get it(!)”; meet it with confusion, and the scornful glare on the front sleeve is directed at you, specifically. On “Mission Impossible” – one of two instrumental covers of Lalo Schifrin’s 1966 original (“Mission Impossible 2.0” appears six tracks later) – she sounds like an amateur guitarist strumming apprehensively underneath the watchful eye of an instructor, a store-owned metronome clicking away off in the distance as she finds her way around the frets. “Jim on the Move,” a playful ballad about a dude named Jim who loves to get around, is laced with dissonant chirps of strings that don’t seem to care (nor understand) what the other instruments are doing, clamoring beneath the unstructured yelps and howls of Mercier-Descloux about this Jim character and his movement (The song’s entire lyrics are as follows: “Jim on the move / Jim on the move / Jim on the move / Jim one the move / Jim, Jim, Jim on the move [repeated]), with the entire conundrum finding itself neatly stitched together by slow-moving bass rhythms reminiscent of foundational Mexican rock music. “As an outsider, Descloux was able to soak up their energy and revolution and use it to fuel the discovery of her own cultural identity and purpose,” Pitchfork’s Laura Snapes wrote in a 2015 review of the LP, the “their” being a reference to New York City’s late-20th Century punk rock protagonists. (it was given a score of 8.2 out of 10, and named ‘Best New Reissue.’) “Press Color isn’t wildly original, but it’s the making of one.”

A large part of what made Mercier-Descloux an outsider then was, especially throughout the creation of this record, her voice. It is widely reported that Esteban, who took on the role of executive producer, often tried to push her as hard as he could into a mode of singing that was conventionally “normal” – lobbying to have tracks re-recorded, looking to get her on board for professional help, and seeking to drastically smoothen her approach long-term. Mercier-Descloux, yet, was intent on not budging. In a 1980 interview with the now-defunct New York Rocker, she reasoned that she was, then, “not at all a writer of words” – rather, she was “using the words completely for what they sound like, how they fit with the rhythms… What’s beautiful is that I don’t speak perfect English but I can get lost in the dictionary and just discover the words.” “No Golden Throat,” Press Color’s third track, is very literally a full space on the album dedicated to her protesting of Esteban’s grievances: she sings the same line over and over again in anarchic variations, perusing octaves and drawls as plentiful as the downtown clubs she grew to frequent in her brief time in New York. “I’ll never have a golden throat,” she croons a dozen different times. It comes off as more of a playful jaunt than a passionate demonstration, but the latter sense is just as manifest.

Lizzy Mercier-Descloux’s most broadly palatable, and widely celebrated work, is perhaps Mambo Nassau, released in 1981. The detail that most informs its content is a career-defining change of scenery: she recorded the album at Compass Point Studios in Nassau, Bahamas, right next door to Grace Jones, who was recording her revered fifth album Nightclubbing (also released in 1981) at the exact same time. “You get exhausted very quickly because there’s no way of getting out of the club scene […] You can be huge there and nothing in the rest of the world,” she said of her transition in one interview. “Thousands of groups never get out, they try to play Boston and California but it’s a disaster. Look at the Lounge Lizards, no label wants to sign them and they get the best crowds, sell the most tickets, it’s been nearly two years. They said to me the other day that they reckon they earn $30 a week, so they are going to stop.” (A good question to ask yourself here would be: have I ever heard of the Lounge Lizards?)

The music on Mambo Nassau is just as sweet as it is eclectic and wide-ranging; it wraps a tight fist around your throat one second and kisses you on your cheek the next, while the constant outcome on each opposite pole is that you come away having felt something tangible. On “Room Mate,” the album’s most popular song to date, Mercier-Descloux goes from primitive yelps about laziness and mix-ups, heavy Africanized bass guitar and tribal-esque drums accentuating her growling urgency, to – in a relatively sudden transition from verse to chorus – concentrated bliss, fluttering whoops about whirling dervishes and gold, the shimmering glam guitars of the B-52’s working in conjunction with newly bouncy, effervescent bass notes to replace the barbaric intensity of the first set of lines. It’s one of those moments in music where, even if you don’t understand a word that was said, you are forced to at some point find yourself reproducing the sound in gibberish faux-lyrics in the middle of your kitchen. One is left with the skittish mannerisms long after the song fades out: “Just like the whirling, whirling…HEY! Der-vishes! Just like Orianaaaaahh….woo! Just like the whirling whirlingggggHA! Der-vishes! Just liiike Oriana na nah nah, HEY!”

At the same time that she was making such buoyant music upon having moved to the Bahamas, many close friends and collaborators have said that she was very prone to being taken advantage of by men she had worked with, all the while being hurt by a plethora of antagonized ex-boyfriends that went on to plague her artistry long-term. Questions about the life she lived beyond music start to become applicable around the release of Press Color, when one learns that it had originally been intended to be a group LP, but it was instead accredited to Mercier-Descloux against her wishes. This sense of imbalance is only intensified by the fact that, as she told a Belgian publication at one point, there were certain songs – like her cover of Arthur Brown’s “Fire,” which is Press Color’s opening track – that made the final cut, although she herself did not like them. With Esteban’s constant pushing (according to a former boyfriend, he “always saw her as his ticket to stardom, as his big star,” a dynamic about which Mercier-Descloux “didn’t really give a fuck”), too, such a claim does not begin to feel very far from reality.

Mercier-Descloux herself, contrastingly, often addressed these ideas with vehement denial. “No, not at all,” she told one Creem journalist who had asked whether she felt as if she was being exploited. “I mean, I write the music that I’m doing, I’m not only performing… I mean—I’m not just used by some male musician who’s going to dress me up and have me to dance just to look sexy on stage and just be a support for some kind of music.”

“Those who refuse to get out of the underground are often bitter and stubborn.”

The narratives surrounding her possible exploitation, and upright denial of it, present a wistful dichotomy that may well be applied to her artistic career writ large: the obvious fact of the matter is that her career was not entirely glamour and glitz – but it’s either we frown at the abuse, at whatever level it existed, or find comfort in the smile she wore on her face through it all, no matter how kosher or superficial it may have been. How believable, one eventually becomes forced to ask, is Lizzy Mercier-Descloux’s grin after all? It appears on the same sarcastic face that pouted, aloof, alongside Patti Smith in a canon of obscene two-piece menswear suits and Soviet propaganda. It made its bed, too, on the same quizzical visage that either invites one into, or dissuades one from engaging with, the outlandish music of Press Color. It doesn’t care – or, in the words of the aforementioned ex-boyfriend, doesn’t “really give a fuck” – about your perception nearly as much, if at all, as whatever may be causing it to exude that sense. And for that matter, unless we are someday able to translate the indistinct shouts and clamors that populate her discography, we will never know exactly what that is.

An interesting thing about Googling Lizzy Mercier-Descloux, besides the Image search result being populated with images from one single photoshoot, is that unlike the case for most deceased artists, her “years active” range ends in 1999, five years before her death of ovarian cancer in 2004. This is because, after a number of shelved projects, pulled funds, and episodes of stark abandonment at the hands of her eventual label, she opted to definitively step away from music once and for all that year, tired of chasing its compelling asymptote with no cushion to fall back on. Somewhere in the process of recording her landmark 1984 album Zulu Rock, she used the music video shoot of popular single “Mais Où Sont Passés Les Gazelles” as an excuse to spend eight hours interviewing Soweto natives about the challenges they faced under the dominion of Apartheid. The book she intended to publish about it upon her return home, along with the unfinished musical legacy she was forced by circumstance to stop constructing, remain eternally unseen by human eyes, and unheard by human ears.

💿 💿 💿

My own introduction to Lizzy Mercier-Descloux came somewhere in the early fall of 2020, after the drummer of a band I had interviewed for an obscure print-only publication put a song of hers on her Instagram story. The track was “Hard-Boiled Babe,” a single from her debut album that was also included on her posthumous compilation LP Best Off (2006). I mindlessly favorited it on Spotify as part of what had been, up to that point, an ongoing faux-attempt to follow musical rabbit-holes from the real world in resistance to the growing, systematic pull of apps like TikTok as means of discovery. I did not listen, and to this day, still have not listened, to the song in its entirety. It went against everything ingrained within me by the hip-hop adjacent, niche punk scenes I had grown to foster an ear toward: words to which I could associate meaning were replaced by primitive shouts; clearly-implemented verse-bridge-chorus structures gave way to freewheeling, churning mayhem; there were no power chording guitars nor cloudy backbeats, but dissonant violins that clashed with everything else that seemed to be within hearing range. The only trace of it that exists in my mind is its incongruent accordion, which made me think of the Krusty Krab upon my first listen, with its oddly eerie sense of knowledgeable displacement among the curls of Mercier-Descloux’s seductive foreign croon.

“When I am working, I am not interested in how my work might affect people.”

I would not come across her name again until about a year later, when, whilst drowning in the sudden overflow of homework that warranted my first few days as a college student, “Room Mate” was cued up in a personalized playlist curated for me by Spotify on a weekly basis. I was annotating a lengthy essay on “Black Representation and Western Survey Textbooks” by Kymberly N. Pinder, between yawns, amidst overbearing air conditioner in the basement of a campus library – Mercier-Descloux’s unpalatable yelps, unlike my first introduction to them, were now what woke me up rather than put me to sleep. I was surprised to learn, after minutes of perusing my favorited songs, why the name had sounded oddly familiar when it flashed across my screen. Surprise turned to desperate curiosity over the series of days that followed; there was an abysmal gap between the uninviting howl I had rejected in fall of 2020 and the colorful stimulant that greeted me now, and I suddenly wanted no more than to fill in those blanks. The night after my encounter at the library, I had been looking into the ideas of Hannah Arendt for a German studies class centered around her work, while “Room Mate” blasted on endless repeat in my headphones at gradually increasing volume. (When a kind girl on my floor entered the common room to offer me chicken noodle soup, she had to raise her voice several octaves in order to get me to hear her over the music. I still wonder, and feel bad about, how long she must have been standing there with lukewarm chicken noodle soup in her outstretched hand.) One day afterward, I watched the clouds go from an illuminous yellow to a cool pink as I sat on a rocking chair at the entrance of my residential building, floodlights gradually switching on around me, and hordes of festively-dressed freshmen beginning to pour out the door for a mandatory welcoming party that would be happening in about thirty minutes – Mercier-Descloux’s music was once again blasting into my ears, this time Press Color, and I was still sitting there, in my own world, desperately trying to understand it. Again, much like it happened with the girl and the chicken noodle soup, I saw figures gesture towards me in my peripheral vision, but the yelps that battered my ear canals presented a separate polar vortex that forced me to value its trance over basic human courtesy: yes, this too, I still think, and feel, very bad about.

Lizzy Mercier-Doescloux’s music operates in this way, where although the entry point is practically invisible – if existent at all – stumbling into it entraps one into a never ending chase, where the asymptote of actual understanding is unattainable, but the process itself is deified. It is very much like the mystical plight made famous in Alice In Wonderland. The chances of Alice falling into the rabbit-hole were relatively miniscule; there was no arrow pointing to its opening, nor was there any conventional rationale for anyone ever having to climb in for themself. (It was, quite literally, the mischief of a hare with a cockney accent [at least in the film remake] that did the trick.) Yet, once Alice found herself inside the apparatus – much like myself and many others, with the music of Lizzy Mercier-Descloux – investments in the outside world grew to disintegrate, and all paths led to an increasingly intensified exile into already-established systems of no human relatability. Listening to Lizzy Mercier-Descloux, you go from disillusioned to intrigued, then from intrigued to bedeviled. The point of escape is just as small as the point of entry, and you are enslaved to your confusion until you muster whatever form of understanding is necessary to set you free.

This is a construct that is consistent with Arendt, whom I had been reading extensively throughout the days that saw my reintroduction to Mercier-Descloux. The first ostensible similarity between Arendt and the singer is that both were, at certain points in their respective careers, regarded as sell-outs by the very demographics from which they emerged: Arendt, in the sense that much of her writing offered unbiased, never-before-heard criticisms of her very Jewish culture immediately after the Holocaust, and Mercier-Descloux, in the sense that her 1981 signing to CBS Records looked to many of sharers of her underground upbringing as a sort of backstabbing. (“The underground—that so often means that you just lack means,” Mercier-Descloux said at one point. “It was good at the time when I was doing my musical apprenticeship, but it doesn’t interest me any more. Those who refuse to get out of the underground are often bitter and stubborn.”)

There is a specific line in one award-winning interview Arendt gave to German journalist Günter Gaus where, upon being complimented by her questioner about how he considered her to be a philosopher despite her gender, she says – just after exclaiming that “It (philosophy) does not have to remain a masculine occupation! It is entirely possible that a woman will one day be a philosopher…” – “Well, I can’t help that, but in my opinion I am not. In my opinion I have said good-bye to philosophy once and for all.”

“In this case,” I wrote in scrawled black ink in a makeshift notes section by the tiny right-hand margin, “it’s not the masculine suppressing the feminine – it’s the feminine suppressing itself. Does her humility come from her own heart, or is it out of adherence to the industry?”

It becomes irresistible to ask yourself similar questions about both figures. Each operated as a backwards-facing catalyst amidst a zeitgeist that pivoted in a certain direction – one as a critic of her own creed amidst its most difficult decade, and another as a cross-dressing impersonator of deceased French poets who happened to have a soft spot for U.S.S.R merchandise – and still, no matter how iconoclast they were, there was always a much larger framework under which they were irreversibly subject. Rebellion only goes so far in industries like those of scholarly political theory and contemporary music, and at some point, whether it is seen as part of the subject’s legacy or not, repercussions are felt no matter how inspiring the fight against them.

In Arendt’s case, she was a cigarette toting, unspeakably chill character who – again, in the words of Mercier-Decsloux’s ex-boyfriend – “didn’t really give a fuck” about the countless condemnations she received from peers and superiors alike over the course of her writing career. (“When I am working,” she said later on in the Gaus interview, “I am not interested in how my work might affect people.”) She remains a writer who, even after death, somewhat suffers from the influence of her rebellion in that her work is extensively approached under the pretext of controversiality, rather than intellect. She existed outside of the system, and the system remains a standard against which she will ceaselessly be measured.

For Mercier-Descloux, moreover, the impacts of being subordinate – willingly or not – to a system that devoured any and everything that had the audacity to look it in the eye, manifested themselves even before her 2004 death. The recording of Zulu Rock, for one, saw her record organic jam sessions with Johannesburg locals in goodwill that was right in line with her longtime cultural curiosity – only to be accused of having plagiarized some of the area’s most popular songs, which led to positive reviews being pulled from magazines, career-altering funding being revoked by CBS, and her band being held hostage by the Praetorian government until they agreed to shelf a separate album they had been working on. Zulu Rock’s successor, One for the Soul (1985), came at the heels of Mercier-Descloux’s longtime CBS mentor Alain Levy leaving the label for PolyGram France; amid even more financial shortcomings, it was yet another record that failed to catapult her into the general public eye. She would go on to record one more poorly-performing LP, Suspense, in 1988, before ultimately calling it quits. “It’s almost incomprehensible that Descloux was allowed to release as many unsuccessful major label albums as she was,” Laura Snapes of The Guardian wrote in a 2016 Pitchfork assessment of Mercier-Descloux’s legacy. “Nonetheless, she had grown accustomed to handsome recording budgets and label heads who were willing to finance her exotic excursions, so after Suspense was DOA, it’s little surprise that slinking back to the underground held no appeal.”

Rather than return to the obscure musical scene from which she emerged, Mercier-Descloux opted to venture into painting and writing, two mediums that bore even less fruit – that is, if their products ever saw the light of day – than her final string of musical releases. After bouncing around between landmarks including Guadeloupe and Happonviliers, both in France, she received her diagnosis for ovarian cancer in 2003. She intentionally chose not to pursue traditional treatment options. In the several months that saw her body gradually decay, she spent her final days seeking to reconnect with old friends, partners, and correspondences to muster some form of closure – her last such act was an exchanging of goodbyes with Esteban in a Parisian hospital, after which she passed away in Corsica on the 20th of April.

A tertiary level at which Mercier-Descloux suffered from her own rebellion is the posthumous acknowledgement she received from her own hometown. For the aforementioned Pitchfork essay, Snapes contacted French-born journalist Simon Clair, author of Lizzy Mercier Descloux, une éclipse (2019) – he said of the matter that “The public were unmoved by her death and French newspapers barely mentioned it.” Lizzy Mercier-Descloux meant for France’s popular culture essentially what a coat of arms would mean for a freshly-implemented bare flag; she was the sudden face of a long-mundane relevance into the musical conversation that was taking the world by storm, one of few things, if not the only thing, connecting her country to the far-advanced infrastructure that whizzed around it for decades on a global scale. No longer was French rock “like English wine,” as John Lennon once put it, but it was now afforded its own eclectic spin – and, more importantly, its own place on the map. Still, in a change of sentiments most likely predicated upon this feeling of betrayal, France did not acknowledge her life, nor her death, when she passed away (in Paris, for that matter). Behind all the makeup, the costumes, the perplexing multicultural music, she was a traitor – and when all was said and done, venturing beyond the borders of her stomping grounds secured her erasure from the very same history book she helped to author.

Lizzy Mercier-Descloux’s legacy was more fittingly honored, alternatively, in the underground US-based infrastructure within which it began building its foundation. CBGBs, the East Village club that saw her play gigs under Rosa Yemen and her own namesake alike over several formative years, hosted her wake to a burgeoning crowd of punks empowered by her influence. “It was really funny to see how many people felt they were totally possessed by Lizzy, how she was capable of making everyone feel that way,” Seth Tillet, Mercier-Descloux’s longtime photographer, told Snapes.

One of the most full-circle manifestations surrounding her death – a rare ostensible period (the punctuation mark) in a legacy drowned in unanswered questions – came later on in 2004, when Patti Smith performed in Le Bataclan, a famed theatre in Paris. The door to the venue bore Smith’s own name – but inside, behind her onstage, the sole decorative elements were the terms “Lizzy Mercier-Descloux” and “1956-2004.” The concert came two months after Mercier-Descloux’s death, and during her performance, Smith dedicated one somber song – “Easter” – to her late friend.

“The same subjective power anyone utilizes to draw connection to her anarchic howls, can be wielded to rewrite the air of their abrupt cutoff.”

It’s wistful to think that Smith and Mercier-Descloux went from flocking the streets of Soho in ancient French garb, their youthful, rebellious stares penetrating the camera lens (and what would eventually be the Google Images search results of later decades), to one eulogizing the other in front of hordes of fans who likely did not know what she was talking about, in a span of less than three decades. For figures of their stature, there is the unrealistic-yet-unshakable sense that they will, indeed, live forever. But forever loses its status as a superlative when the overarching entity of business enters the equation. Had it not been for spur-of-the-moment executive decisions – whether those be pulled funds, shelved albums, or revoked rave reviews – the overarching legacy of Lizzy Mercier-Descloux may very well have reached far beyond the maddening lows it managed to brave long-term, potentially crossing even more cultural lines than she did while she was alive, with the added never-to-be-realized possibility of enabling an entire legion of musicians to continue in her multi-flavored international pastiche. As mentioned before, intently delving into the music of Lizzy Mercier-Descloux launches one into a world of chasing something, an end, that isn’t real. This is because there is practically zero conclusion to the loose threads she left behind. Any conclusion you come to exists in your head; there is no firm punctuation, only question marks and everlasting ellipses.

In many ways, this plight is a direct result of her choice to create outside of the graph, rather than chase its elusive asymptote. “– [Lizzy] was very instinctive,” Esteban told Tidal in 2015. This enacted itself as, just as much as it was a unique intuition, a career-long Achilles heel. “She never wanted to be a professional or learn too much. In a way that was good, but that was also her limit. It’s great for the first album; when you’re fresh and want to discover everything – even if the professional musicians and the studio say no. So, in the beginning it’s a quality; after a few albums… it’s not a quality anymore. You have to learn things in a way. But she was like that, more of a poet than a singer and musician.”

When one has full understanding of this curse, one that held her back as commercially as it pushed her forward creatively, even the most effervescent of her songs become painful to listen to. The mangled croons of “I’ll never have a golden throat” on “Golden Throat” go from playful banter to eerie foreshadowing; the ever-changing instrumental makeup of “Room Mate” goes from carefree ecstasy to a painful reminder that the very same sounds landed her a career-killing plagiarism lawsuit; even the slow, amateur Jazzmaster strums of “Mission Impossible” and “Mission Impossible 2.0” begin to sound less like a bright-eyed novice on the uptick, and more like a self-destructing tragic hero who’s too busy having fun to realize she’s going downhill.

If the little conclusive quality to a story like Mericer-Descloux’s is this morbid, however, it may just be more suitable to redirect one’s gaze – permanently – to the book that exists as it is, and not the fact that it will always be unfinished. Somewhere in the unpublished autobiography Lizzy Mercier-Descloux never got to write, there are probably images of the singer dressed in mid-19th Century garb, pouting alongside Patti Smith in the midst of Communist flags, white walls, and youthful infinitude. Both the nonexistent ending to Mercier-Descloux’s story, and the blooming New York City punk rock community in which these photographs were taken, only exist in the mind of the beholder – conveniently enough, the very same nucleus generating any and all perceived beauty in Mercier-Descloux’s work. The same subjective power anyone utilizes to draw connection to her anarchic howls, can be wielded to rewrite the air of their abrupt cutoff.

Mercier-Descloux was, if anything at all, someone who beamed at the prospect of such approaches someday being applied to her own legacy. She idolized women in rock who graced their niches as standalone figures, removed from the subordinate shadows of male counterparts – much like the rationale she often maintained to refute claims of exploitation – and closely followed their influence until she, herself, became the pioneer.

“Women,” she wrote of Smith in one Rock News article, “are usually groupies or the silent circle of photographers, managers, or the soul sister of rock’n’roll. The myth of the sexy pin-up, unthinkable regarding Patti, has been crushed beneath the foot of this strange, neurotic person, who is possessed of a sexual power as unknowable as it is vast.”

Look upon an image of Mercier-Descloux sarcastically frowning alongside her idol in 1976 – whether lifting the hem of Smith’s skirt, holding her hand, or standing, all alone, with fierce, gripping eyes – and it becomes clear, ever so slowly, that such an assessment is just as applicable to her.

One reply on “The Opaque Iconoclasm of Lizzy Mercier-Descloux”

very nice navigation in mist of LIZZY; “fog horn blue” thank’s. Julien