The Not-So-Friendly Future of “Mars Attacks!”

Mars Attacks! teaches us that no matter how much we think we know about the unknown, it remains unknown—and deadly. (Photo: Scene from ‘Mars Attacks!’/Tim Burton Productions, Warner Bros.)

SAMUEL HYLAND

In the markedly lengthy opening title sequence of Tim Burton’s 1996 alien spoof Mars Attacks!, a menacing assembly of uniform UFOs congregates dangerously close to our stratosphere, equally-menacing music blaring in the background as endless A-list names—Jack Nicholson, Michael J. Fox, Danny DeVito, Sarah Jessica Parker, Natalie Portman, Tom Jones, etc.—float in and out of view. In and of itself, the moment is a striking double-assertion of what exorbitant ethos Burton uses the film to accomplish: as much as the alien attack might as well be an onslaught of our own culture, the very same oversaturation of our collective self may be as threatening as any extraplanetary force. As far as 1996 sci-fi goes, cinema history has been retrospectively kinder to Independence Day, the Will Smith-starring thriller that sees humanity exact desperate revenge upon genocidal extraterresials on the 4th of July. Even given their chasmal differences, Mars Attacks! being a slapstick caricature and Independence Day being a psychological nailbiter, both films hail from, and encapsulate an era that was relentlessly snowballing towards the existential dread of a new century bearing new unknowns—where do we draw the line between us and them, and when exactly are we going to have to make that distinction?

“It is no longer just us. We have become one planet. And soon, we will become one solar system.”

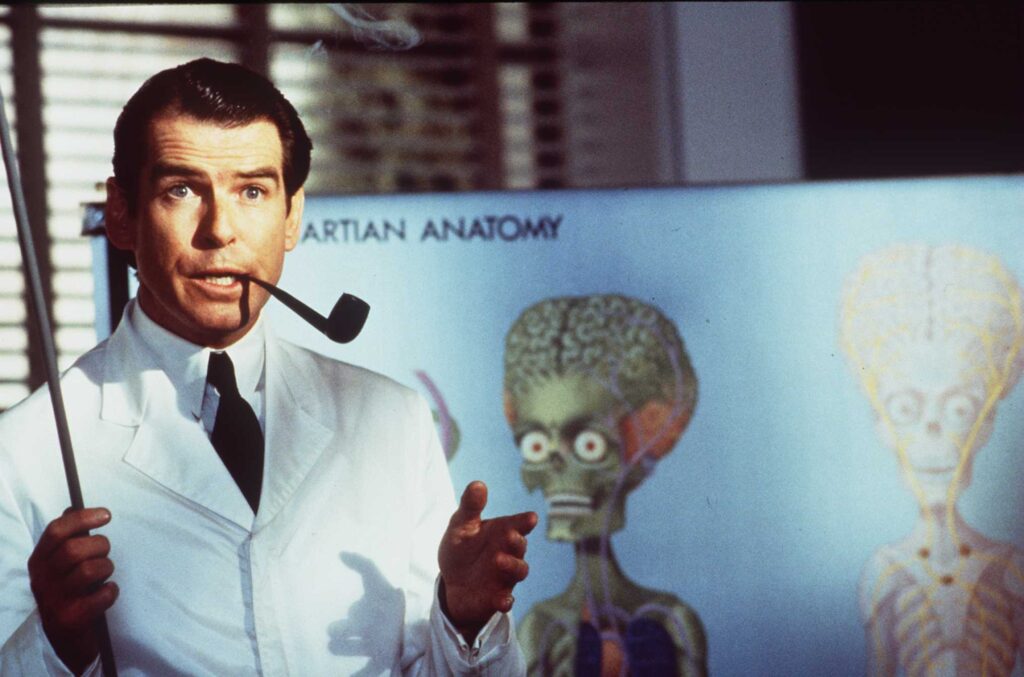

Though in real life, the manifold us-versus-them dynamics plaguing society did not entail too much extraplanetary warfare, Mars Attacks’ premise was, fittingly, the very thing comprising its excessive opening title sequence. The film’s plot line opens with a contemplative President James Dale (Nicholson) shuffling several hazy black and white UFO photos in his palms, squinting his way through each before glancing upwards to consult a room full of Cabinet members. Everyone in the Oval Office besides General Decker, a hardcore, aviator sunglasses-wearing military personality whose entire character is built on being outspoken about nuking Martians, seems to be oddly chill about what’s ostensibly a global crisis. President Dale wonders whether the matter should be withheld from the public. General Casey, Decker’s military peer, questions the need for arms—do we know they’re hostile? Professor Donald Kessler, the White House’s resident pipe-smoking science wiz, doubles down on the optimistic consensus: “We know they’re extremely advanced technologically,” he says, annoyedly blowing a smoke cloud, “which suggests, rightfully so, that they’re peaceful.” General Decker tears his hat from his bald head in disgust. “An advanced civilization is, by definition, not barbaric,” Kessler continues.

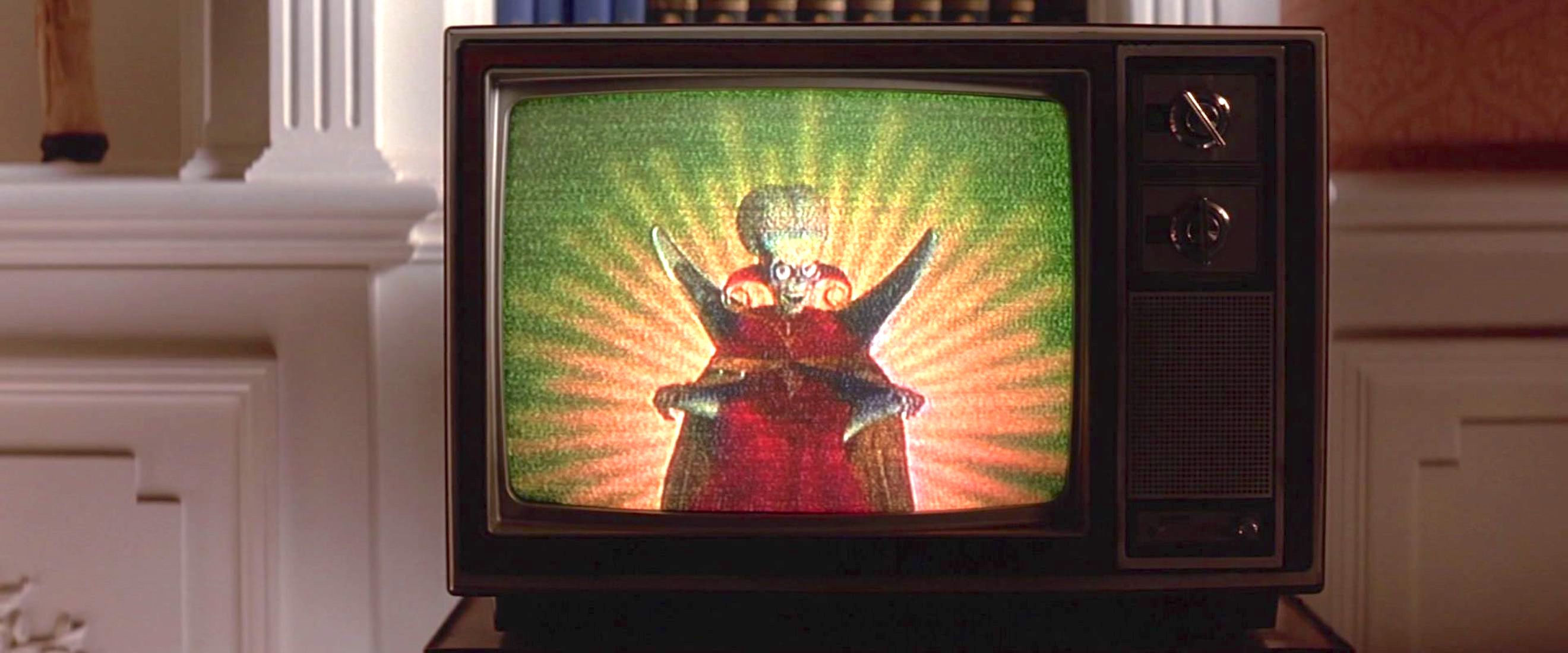

As the White House deliberates, we are transported to the interior of a swanky Egypt-themed Las Vegas hotel, wherein an upstart promoter quarrels with his pacifist wife, and a retired boxer struggles to support his family on miniscule wages (not including his being confined to a ridiculously dignity-diminishing pharaoh costume). Ad interim in New York City, Nathalie Lake, a racy television personality played by Sarah Jessica Parker (think: the human manifestation of Madonna’s “Material Girl” if it were to be anyone but Madonna) crosses her legs in a futuristic pod chair, phone-toting executives making frantic calls on the other side of the studio’s glass window. As Lake’s boyfriend and co-worker Jason Stone admires his hair in a replay of a previous broadcast, Lake nonchalantly phones him with the news that President Dale is cutting in on today’s show time to deliver an urgent public address. We see Dale seated fireside in the Oval Office, reading from a teleprompter as an ecstatic group of White House onlookers (excluding, of course, the pouting General Decker) looks on. “I feel that this is the perfect ending to the Twentieth Century,” he declares, opting to embrace extraplanetary life rather than declare war upon it. “It is no longer just us. We have become one planet. And soon, we will become one solar system.”

A large-scale Welcome to Earth event is held in Pahrump, Nevada. There is an enormous military procession, a raucous crowd of onlookers beside themselves with anticipation for history, and, not before long, from out of nowhere, a large flying saucer touching down on a conveniently-placed red carpet. A group of large-brained, helmeted, bug-eyed martians emerges from the warship, and their leader immediately engages in a translated conversation with General Casey. When the translation machine spits out a high-pitched “We Come in Peace!,” awkward tension turns to mass jubilee. Someone in the crowd lets out a dove. The Martians shoot the dove with a crazy laser-pointing ray-gun flamethrower device—soon after which they start shooting everyone. It turns into an all-out massacre; Stone, Casey, and private Billy-Glenn Norris, a patriotic trailer park kid played by Jack Black, are killed in the melee, while Lake and her pet chihuahua Poppy are abducted.

Back in the White House, the Cabinet speculates that the dove may have been a universal symbol of war for the Martians, and urges Professor Kessler to renegotiate with the species. The aliens say it was all a big misunderstanding, are invited to address the U.S Congress, and proceed to massacre them, too—this time, with Kessler being the abductee. Much of Mars Attacks! Is rooted in this construct, with humanity dishing out second chances and alien-kind dishing out bloodbaths in return, until, when the Martians finally make a full-fledged and fully-fleeted descent into planet Earth in hopes of enacting a genocide, they are amusingly killed off by a lanky, unsuspecting teenager broadcasting his grandmother’s horrendous oldie music—so horrendous, in fact, that it causes the Martians’ brains to blow up once they’re within earshot—from a public radio station.

Though the film is mostly, as made clear by an ending like its own, a comical, kid-friendly look back at the Communism-influenced alien epics that dominated the 1950s, the ethos it channels is one wrought by early-stages existential dread, the sense of being observed by something that knows more about you than you do of it, the terror of an unfamiliar “them” that threatens a familiar “us.” Much like President Dale and all but one member of his Cabinet, an immediately accessible instinct when faced with something capable of complete destruction is to forge an alliance and save oneself. The aliens exploit this influence by wearing humanity’s sole desire from their kind—that they “come in peace!”—on their sleeves, using the subsequent relaxing of guards to kill, capture, and terrorize whomever they want.

The second, and most relevant, primal quality Tim Burton’s aliens exploit, yet, is the relentless intrigue of the unknown. The people of Mars Attacks! persistently want to understand more about their otherworldly visitors—devoting extensive research to a translation machine, subjecting the corpses of fallen Martians to extensive autopsies, loving the first massacre so much that they invite their assailants for seconds, then thirds, then genocide—and it is this exact inherent curiosity that would have very well wiped out the entire human race had some teenager’s grandmother not been a devoted Slim Whitman enthusiast. The undefined seduces us, and while we spend our whole lives running after its various manifestations, we also make ourselves irrecoverably susceptible to any cracks that ever decide to appear in the road. In a world where everything makes sense, there typically aren’t any such cracks besides the gaping hole called the future that always lies directly ahead. But how safe would we be if something did happen to screw up the order of the universe? If a fissure suddenly appeared beneath us in our endless sprint towards defining things, unless someone were to have a Whitman-loving grandmother and access to a larger-than-life, globally-reaching radio antenna, the discernible truth is that we would likely all be casualties in a Tim Burton spoof.

“How much of your being would you be willing to give an alien species? The answer is an ecstatic “None of it!!!,” until they’re right in front of your face.”

One of the most captivating scenes in which we see this dynamic play out comes when, fresh off of massacring the U.S. Congress, the Martians send one of their own down in the disguise of a voluptuous woman. Speechless, the “woman”—a suspiciously tall, stone-faced blonde who glides on hidden wheels and only uses her mouth to chew bubblegum—flirtatiously approaches the window of a cab occupied by Press Secretary Jerry Ross, an overly-gullible character whom we have, up to this point, already seen be seduced cabside once. Ross speaks to, and is ignored by, his silent partner, all the way through the White House’s foyer, past a secret red button hidden inside a bust of John F. Kennedy, past the door of the hidden chamber said red button unlocks, and into a lavish leather couch, where, finally, upon reaching inside the “woman”’s mouth to extract her chewing gum so that the two can make out, Ross promptly has his index finger bitten off and spat out into a nearby fish tank.

After Ross is easily killed, the alien, now gradually shedding its costume, makes its way to the President’s bedroom for a barely-missed assassination attempt. The construct is ever clearly, and ever crudely, played out before us: we are the drooling perverts diving head-first down the rabbit hole, and the silent unknown is the shapely animatronic leading us on to the bitter end. In Mars Attacks!, the people of the world are enthralled with their Martian visitors solely because of what they can offer them conceptually—whether that offering entail scientific advancements, technological knowledge, or the medallion of extraplanetary compatibility. The Martians want nothing from us but our obsession: so long they have that under their belts, everything on our planet belongs to them. How much of your being would you be willing to give an alien species? The answer is an ecstatic “None of it!!!,” until they’re right in front of your face.

👽 👽 👽

If anything, differences between the levels of interest Tim Burton’s humans have in alien-kind and vice-versa are most accurately illustrated by the “research” endeavors captives of opposite species are subjected to throughout the film. For one, when White House officials get their hands on the corpse of a Martian killed in the Welcome to Earth massacre, the tiny body is stretched out across an operation table in a room populated with squinting officials, white lab coats, and blinding overhead lighting. “What confounds me most, gentlemen, is the lack of genitalia,” Kessler remarks to his lab assistants. “And of course down here we have the aorta; up here we have the sphinx. Notice the highly developed cranial nerve system here. This explains, of course, the cerebral arteries. And if we notice down here, behind the optic chiasm”—he digs a gloved hand into a rectangular hole in the creature’s brain, extracting a fistful of stretchy, green slime—“several glands… very curious.”

Alternatively, in the Martians’ mothership, the aliens’ “research” entails switching Lake’s body with that of her dog, and completely dismembering a still-alive (and well) Professor Kessler to the point where he’s a disembodied head curiously bouncing wherever he can. (By the end of the movie, we play host to the strange sight of Kessler’s head kissing Lake’s, which is now the top half of a chihuahua centaur.)

“Regardless of all the research we do on the future, the future certainly isn’t doing any on us, and somehow, no matter how well-prepared we think we are, it always wins.”

Alien movies, both in the Red Scare era they emerged from and the increasingly contemporary film landscape they’ve grown to populate, tend to play on the idea that extraterrestrials, if existent, are the ones endlessly fascinated with us. They swoop down unannounced from their flying saucers, picking up unsuspecting humans via levitational airlift or manual hand-carry, en route to a series of trials, tests, and probes that give them the answers to whatever it was that they were curious about then send them back on their merry way to Mars. The trope is one that, ever the relic of the society that manufactured it, reeks of self-centeredness once slightly defamiliarized: for what reason would a technologically-advanced species from another galaxy, light-years ahead of us both in space and knowledge, go on a suicide mission to witness our ineptitude firsthand? Aliens caring any more about us than what our heads would look like on dogs’ bodies is fantastical at best, and the star of any such show is forged by a familiar narrative—where a fixation we aren’t comfortable admitting is cast onto its subject, and we get to enjoy the benefits of being the innocuous victim.

Mars Attacks! both arrived at, and snapshotted the energy of, a transition into the 21st Century that burgeoned with anxious dread. The ensuing years would see us obsess over Y2K—an imaginary digital apocalypse that we constructed entirely by ourselves—theorize about a million different ways that the world was surely going to end, and drive ourselves madder and madder with wild speculation as the future drew closer. We, in this context, are once again the self-obsessed sufferers of an assailant that, for all we know, really couldn’t care less about us and our problems: regardless of all the research we do on the future, the future certainly isn’t doing any on us, and somehow, no matter how well-prepared we think we are, it always wins. We are examining every last trace of tomorrow in a white-lit surgical room, lab coats, diagrams and odd medical instruments at-hand. For all we know, the future could be somewhere far away, switching our heads with those of our dogs, and taking us apart and putting us together again for sport.

In a later portion of Mars Attacks!, upon being confronted by his wife about steadily-rising dangers, the aforementioned upstart promoter retorts, with zest: “You’re worried about yesterday—I’m worried about tomorrow!” He is among the first killed by Martian forces when they descend on Earth for the final, genocidal push. Oftentimes in the 21st Century, whether knowingly or unknowingly so, we illogically take on the role of the tough guy going head-to-head with the universe. We try to figure out things that aren’t clear; we scoff at the weatherman’s inaccuracies; we want the way quicker than the quickest way, so much so that every time we look something up, Google cannot help but awe us with whatever crazy figure our query produced (however many million results in zero point however many seconds)—which is too bad, because we’re too busy scrolling to read it. This isn’t to say that curiosity ought to be frowned upon—but if the future will always be an unknown no matter how much we know about it, there has to be a moment where we ask ourselves what the point of speculating is.

By the film’s end, it seems as if some version of this realization has dawned upon President Dale. He sits in a closed-off deliberation room, now a crime scene of repeated emergency buzzer noises and red flashes, pulling away at his hair as a telephone rings off the hook nearby. Mister President, a voice tells him, the President of France is on line two! Disgruntledly, as if he’s doing it for the one hundred and seventh time in a row, he picks up the phone and drags it to his ear: the President of France is ecstatic on the other end of the line, practically pissing himself through updates that he’s with the Martians right now and they’re close to reaching an agreement—that is, until he is promptly cut off by the familiar sound of a crazy laser-pointing ray-gun flamethrower device. Dale himself, even despite his seeming keenness on what’s going on here, meets his end when he offers a truce to the Martians that surround him. When he extends his arm for a handshake, he is stabbed in the chest by a sharp weapon that protrudes from the palm of his would-be ally.

In his final act as President before this demise, Dale finally obliges to let a hysterical General Decker go forward with the nuclear warfare approach he’s been suggesting all along. It is in this scene, and this scene alone, that the comical, otherworldly jive-speaking space aliens fully embody the future they represent, in face of a generation hellbent upon mitigating its force: a matter of seconds after the nuke is launched into space, it is intercepted by the mothership, and turned into a plush toy-esque device used by the creatures on board as a quick source of amusement. The future is too far ahead to be affected by our machinations against it, but also too close in proximity to not be flattered.

As mentioned prior, the Martian race is eventually eradicated by an unsuspecting teenager and his grandmother teaming up to blast Slim Whitman music across the globe via a local radio station. What makes this all the more sensible in context of our race towards the future is that, unlike all the characters that died trying to get ahead of the curve—including the teenager’s brother (Jack Black) who was killed in combat, and the remainder of his immediate family, who were literally picked up and obliterated while loading up shotguns in their trailer home—he really didn’t have a plan. One second, the murderous aliens were not there, and the next second, they were. It required him to think on his feet, rather than shit himself trying to frantically construct a box to operate in, and while a majority of his human counterparts died trapped in their own mental confines, it was his lack of preoccupation with predicting the future that allowed him to actually survive it.

“You’re worried about yesterday—I’m worried about tomorrow!”

In his final scene in the film, he and his grandmother are awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor by the President’s daughter (Natalie Portman), in the ruins of the U.S. Capitol. Upon asking whether he can recite a statement he’s prepared, he extracts a crumpled ball of paper from his pants pocket.

“Hi everybody,” he starts, awkwardly and with an endearing glint. “There’s a lot of people in the world who’ve done, like, a lot more than I have. They’re the ones that should be here now, getting a medal. I want to thank my grandma for always being so good to me, and for helping save the world and everything. So I guess, like, now we have to start over and start rebuilding everything… like our houses and—but I was thinking, maybe instead of houses, we could live in teepees, because it’s better in a lot of ways. That’s all I have to say. Thanks.”

Figuring it out as you go along doesn’t always look or sound the best—but if Mars Attacks! teaches us anything, it’s that being an awkward-sounding human on Earth is always better than being a chihuahua centaur in space. And as long as we’re in the present, the choice belongs to us.