The Museum Versus the Public

Museums worldwide sit on the cusp of re-entering vast pre-pandemic cultural roles. Will their soon-coming futures be any different from their divisive histories?

ORLIE WHITE

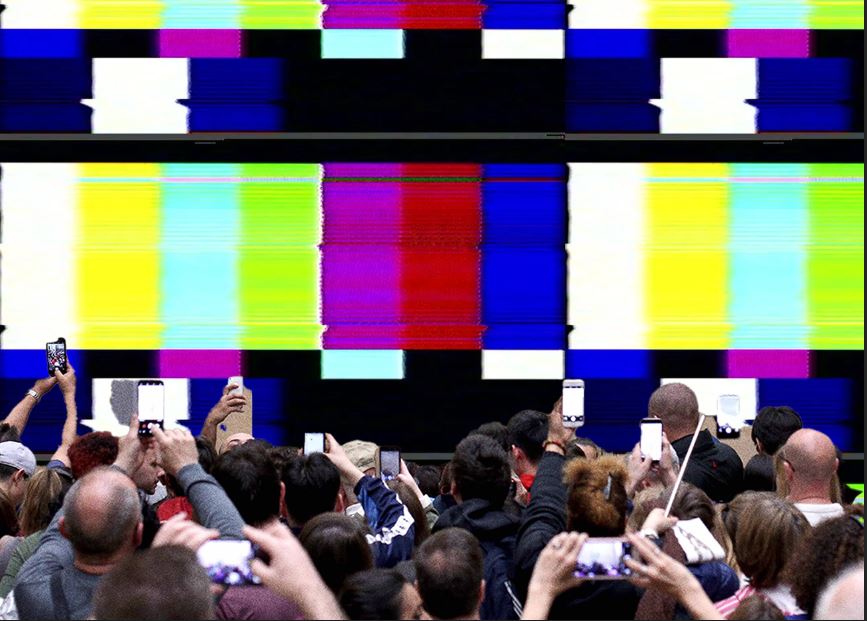

An anxious wife finds her husband contemplating a Raphael painting in the Victoria and Albert Museum. A woman enters MoMA in 2007 and kisses the wall, Catholic visitors at the British Museum kiss glass cases which hold religious reliquaries, and the Brooklyn Museum turns its entire lobby into a food distribution center. Every day, thousands of individuals wander through museum galleries, searching for connections of spiritual means to “masterpieces” and coveted objects carefully hidden behind glass cases that say “look, but don’t touch.” Institutions of art are made for the public, but are greatly susceptible to the influence of wealthy donors and political players. Museums are places where one goes to expand their mind and be confronted with the limits of their own knowledge. Little children misbehave and tourists take pictures. An art class studies a Rembrandt, Ferris Bueller kisses Sloane Peterson. What is the relationship between the public and art museums across western society?

Before we talk about how the public connects with western art museums, we must understand the culture and tradition that western art museums emerged from. It is said that art galleries emerged because royal kings and queens got tired of sitting around all day and wanted something to look at while taking walks through their hallways. In “The ‘Long Gallery’: Its Origins, Development, Use and Decoration,” author Rosalys Coope states that in palaces and royal homes:

“the function of the larger corridor-gallery was more significant in that it served not only for communication and access but as a useful “socially neutral” ground, a place of reception or conversation, lying between the private apartments and the more public rooms of a large establishment.”

Corridor-galleries were present in French and British royal properties in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when the “long gallery” emerged, connecting royal corridors to other parts of the palace. Describing the galleries in King Henry VIII’s palaces, Coope states, “The contents of the King’s gallery, musical instruments, a Mappi Mundi and numerous paintings reveal much about its recreational function…By the 1540s, the “recreative gallery” was a prominent feature of the royal houses of The Bridewell, New Hall, The More, Hampton Court and Nonsuch and of a few non-royal homes…It was not until the second half of the sixteenth century that what be termed the “explosion” in the introduction of long galleries into country houses took place. The long gallery became an integral part of the established sequence of state rooms in an important house, a sequence consisting of a Great Chamber, a Withdrawing Chamber, a Bedchamber and the Long Gallery. One of [the long gallery’s functions] was to provide a place in which to exercise in bad weather and it may be that a particular fondness for exercise on the part of the English might account for the extraordinary length of some of their galleries- embodied in the very name “long gallery.”

“As society progresses and we all expand our minds to include new movements and artwork that reflect different cultures, histories, and perspectives, the art museum serves as a mediator, balancing the interests and ideas of its collective audience.”

Thus, the long gallery was a place for gathering, entertaining, and socializing. Assisting in these activities while also serving as decoration, paintings were displayed on gallery walls, often heroic and gallant portraits of royal family members, monarchs, or historical figures. Coope explains,”These ‘devices’ and the themes of fame, greatness, worthy example of family and dynastic pride were perpetrated in the type of subject found in the wall-paintings or in the pictures placed in long galleries.” Galleries were spaces of diplomacy and politics, along with informal social gatherings. Thus, the people who were able to view gallery artwork were limited to people in the elite circle of royals or powerful political leaders.

Prior to the notion of a “public art museum” or consensus about a general public to begin with, those with money collected and displayed artwork as a means of showcasing power or status. Post-renaissance private art collections in western Europe focused largely on promoting power of a monarch or ruler to his followers, cortiers, nobilities, and rivals in other states. As Tony Bennet explains in “Birth of the Museum”, “the secular collecting practices of European princes and monarchs… played a major role in symbolizing the monarch’s power before and to the popular classes. ‘It is,’ as Gerard Turner puts it, ‘part of the exercise and maintenance of any leader’s power to ensure that his image is constantly before the people who count.” Thus, art became a strategic propaganda tool for people with power, who could display artwork as a means to showcase class, wealth, and power not to the general public, but to a specific audience of “ the ruler’s immediate supporters, the courtiers and nobility, and his rivals in other states.”

Of course, these private collections were never meant to be showcased to the public, because most people were not influential and thus disregarded and overlooked. There are few exceptions to this – that is, art being showcased to a wider reaching audience – however, always at the hands of private collectors for their own political benefit. In 1584, Francesco I de Medici displayed his collection of artwork to the Italian public for a personal and strategic aim. Medici, at the time, was lobbying for the government for public legitimation of the Medici dynasty, and thus, showcased an impressive and very sought after collection of art to the public, curated to impress, flatter, and glorify the prince.

However, during the 18th century, western European nations became more powerful, expansive, and influential due to colonization and growing nationalism. As the Enlightenment movement and its surrounding ideas circulated throughout wealthy and elite circles in Europe and North America, the public museum emerged as a means of enforcing more control, influence, and authority over their societies while fueling nationalism, pride in one’s own culture, and education. As Dr. Elizabeth Rodini writes, “The Enlightenment is when we begin to see specialized collections, including museums devoted only to art—the Capitoline (Rome, 1734), the Louvre (Paris, 1793), and the Alte Pinakothek (Munich, 1836). Similarly, dedicated collections of plants (botanical gardens), animals (zoological gardens), and eventually natural history and ethnographic objects emerged. “The first western art museum as we know it is the British Museum, created in 1753 through an act in the British Parliament. As the British Museum’s website explains:

“In 1753, an Act of Parliament created the world’s first free, national, public museum that opened its doors to ‘all studious and curious persons’ in 1759. Initially, visitors had to apply for tickets to see the museum’s collections during limited visiting hours. In effect, this meant entry was restricted to well-connected visitors who were given personal tours of the collections by the museum’s Trustees and curators.”

Thus, the British Museum became accessible and very influential – not to the general public in England, but to individuals across Europe and North America who were rich, powerful, and wanted to emulate the British Museum model in their own countries. For example, in 1780, John Adams visited the Paris Cabinet of Natural History and wrote the following letter to his wife Portia:

“Here is a Collection from all Parts of the World…When shall We have in America, such Collections? The Collection of American Curiosities that I saw in Norwalk in Connecticut made by Mr Arnold, which he afterwards to my great mortification sold to Gov. Tryon, convinces me, that our Country affords as ample materials, for Collections of this nature as any part of the World.”

Hence, the age of the “public museum” as an accessible institution emerged across western societies. As Tony Bennet writes in “The Birth of The Museum”, “The reorganization of the social space of the museum occurred alongside the emerging role of museums in the formation of the bourgeois public sphere.” An interesting aspect of the formation of these museums is how gendered they were in nature. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, fashion department stores sprouted up all around western society, providing middle and upper class women with a space to discuss culture and life in an elite and fancy environment, where they were also exposed to the latest fashions and cultural trends by department store staff, who were “groomed” to lessons in hygiene, etiquette and grammar; along with, as Tony Bennet writes, “visits to museums and art galleries to acquire the principles of taste,” allowing sales associates to earn the trust and respect of wealthy consumers who saw them as a “living testimony of cultural improvement.” However, their husbands and male counterparts did not have a more eloquent and formal atmosphere to congregate and instead gathered at bars, getting drunk, and not becoming educated on refined society and cultural innovations. The gendered gap in cultural education and intelligence added more of an urgency for wealthy countries in western Europe and North America to develop public spaces of art, for high members of society, specifically men, to congregate as an alternative to local bars as a pastime. As Bennet continues,

“Culture, in this new logic, comprised a set of exercises through which those exposed to its influence were to be transformed into the active bearers and practitioners of the capacity for self-improvement that culture was held to embody…The museum’s new conception as an instrument of public instruction envisaged it as, in its new openness, an exemplary space in which the rough and raucous might learn to civilize themselves by modelling their conduct on the middle-class codes of behaviour to which museum attendance would expose them… provided they dressed nicely and curbed any tendency towards unseemly conduct…The anxious wife will no longer have to visit the different taprooms to drag her poor besotted husband home. She will seek for him at the nearest museum, where she will have to exercise all the persuasion of her affection to tear him away from the rapt contemplation of a Raphael.”

Accordingly, an interesting dynamic was created in museums, which were founded with Enlightenment ideals of freedom, open-mindedness, and accessibility, and yet, remained, arguably on purpose, for a very elite and limited crowd of high society men.

“Transforming the museum space to become one that welcomes and amplifies voices of communities that have been historically marginalized and overlooked will not be an easy task, and will likely call curators and art lovers alike to rethink how such sanctuaries can retain their sacredness while inviting new kinds of visitors into gallery spaces and exhibitions.”

In his 1979 book, The Art Museum: Power, Money, Ethics, journalist Karl Meyer writes, “Since the turn of the century, museum professionals themselves have been trying to define the nature of the art museum.” Today, the nature of the art museum is still rather unclear. Even now, while public art museums claim to be “for the general public,” the people that most commonly visit them represent a specific demographic – one that is educated, wealthy, and white. In “Cultural entrepreneurship in nineteenth-century Boston, part II: the classification and framing of American art,” Paul Dimaggio articulates that every social group needs rituals that enforce common values and beliefs. He adds that “Particularly in the case of a dominant status group, it is important that their culture be recognized as legitimate by, yet be only partially available to, groups that are subordinate to them.” Thus, an art museum acts as a space to recognize and determine artwork that is valued and admired by the common visitor. Moreover, the collection of a museum has to be considered “rare,” “special,” and “sacred” in order to attract consumers. In order to actually preserve this coveted image, museums must distance themselves from the mainstream and produce exhibitions that approach topics from a highly specialized and educated perspective. If museums appeal to relate too much to the general public, or have collections that become too accessible and familiar, they would no longer exist as sought after places.

There is a sense of distinctiveness in a museum, where one feels suspended from time and daily life. Everything on display feels timeless and priceless. This creates a very special, arguably sacred, environment. Referencing the formation of the Boston Museum of Fine Art, Dimaggio continues,

“High culture would have to be imbued with sacredness, and, as sacred, removed from contact with profane or popular culture (see Douglas, 1966.)… In accomplishing this, Boston’s cultural capitalists, and the writers and art historians who assisted them, alerted the initial missions of the organizations that they founded and established a partial monopolization (with educated members of the middle class as junior partners) of high culture that has persisted to the present.”

Part of the sacredness that comes from an art museum is that it is a heavily monitored and highly inspected space. Thus, it becomes a time-warp of sorts of this very stable “high culture.” An art museum often attracts a very selective and niche audience of people who know and understand how to interact, respond to, and understand the sacred aspects of a museum’s collection on display. One has to be taught to feel art. It is a skill that requires comfort and exposure, and familiarity with institutions where art is shown. One has to be able to comfortably wander through a museum, study pieces of art, read captions, look for details, search themselves for an emotional attachment, or try to understand the specific goals, intentions, and contexts of the artists writ large. These skills are not natural for us. They require a cultural familiarity, and thus, end up naturally being the most accessible to people in societies that are either part of, or close enough to, the elite class.

Disregarding the elitist undertones present in Dimaggio’s writing, the question remains: Is it possible for art museums to truly break out of this mold and support the public? Perhaps it starts with each individual visitor claiming and inserting the personal power to use museum spaces in their own unique way. In “Considering the Glass Case,” author Stephen Burns talks about the way that various visitors interacted with religious Catholic reliquaries in a 2011 British Museum exhibition titled Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe. As Berns states, “Whilst the motivations for attending varied, a number of these visitors came with the specific intention of venerating the relics,” even though the British Museum was created by a Protestant body as a secular institution. Thus, museum curators chose to display the Catholic reliquaries behind glass for protection. However, as Berns states, ”Physical proximity to the holy relic is an essential component of [Catholic prayer rituals], which – in the context of the museum exhibition – poses an interesting question. Do display cases sever the relationship between visitors and displayed objects, or can these glass boxes facilitate such acts of veneration?”

Curators at the British Museum chose to display the Catholic reliquaries more as historical artifacts enclosed in glass, and yet, an overwhelming number of Catholic visitors still utilized the presence of the reliquaries as a source of religious prayer and connection. Still complying to museum rules, every day religious visitors would come to Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe and leave kiss marks and nose prints all over the glass cases, getting as physically close to the objects as possible to experience as much of a spiritual and physical closeness as was allowed. Security guards would wipe and clean the glass every night, and yet, on a daily basis, new visitors would leave a physical and devotional mark on the exhibition.

Similarly, performance artist Maria Anwander exhibited an act of rebellion against traditional museum habits in 2007, when she gave the museum walls in MoMA a french kiss in red lipstick and stuck a homemade art caption to the wall which mimicked the style and appearance of the captions of official MoMA artwork. Anwander did not seek permission before her performance art piece. However, the museum was so impressed with The Kiss that they decided to “keep” it. Unfortunately, The Kiss is not currently on view at MoMA. One can imagine that eventually, the lipstick marks faded and the museum caption peeled off of the wall, or perhaps the piece was painted over in white or covered in dust and smudges until someone ended up cleaning the walls. Regardless, Maria Anwander, like many of the visitors at Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe, found a way to engage with the traditional western art museum in a personal and fulfilling way.

Beyond individual measures, the surest way to make museums more accessible to the public is through education. In his 1979 book, The Art Museum: Power, Money, Ethics, journalist Karl Meyer writes,

“The essential dilemma that the art museum poses in a democratic society is that the experience it offers does not readily translate into political vernacular. A high body count at the turnstyle says little about the quality of perception that a visitor may bring to museum treasures. The problem, which existed when the portals of the Louvre were flung open in 1793, has been compounded by the revolution in the visual arts, also incubated in Paris, that gave birth to the avant-garde… [with] the Impressionists… defying the academic tradition in Salons des Refuses, the first of which was organized in 1863.”

As society progresses and we all expand our minds to include new movements and artwork that reflect different cultures, histories, and perspectives, the art museum serves as a mediator, balancing the interests and ideas of its collective audience. As institutions, museums teach us what history looks like, whose creativity is worth remembering, and what voices are worth sharing. Thus, the Metropolitan Museum of Art displaying African contemporary artist Wangechi Mutu’s sculptures outside of its main entrance and indigenous artwork in the lobby makes a statement that such voices and artists are part of the conversation, and are worth honoring, studying, and appreciating.

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, museums have had to redefine their very purposes, what they represent, and how they exist outside of physical spaces. Thus, the role of the museum has expanded to one of community service and connection. During COVID-19, The Guggenheim Museum grew thousands of tomatoes which were donated to City Harvest and provided online access to over 200 art books from its digital archives. The Brooklyn Museum partnered with The Campaign Against Hunger to turn their lobby into a food distribution center to help combat hunger in New York City. New York City’s Lincoln Center – which is planning to stage outdoor venues and performances in the summer of 2021 – also serves the public through blood drives, food distribution sites and polling locations. Google’s Arts and Culture initiative, which started in 2011, facilitated virtual tours of over 2,000 art museums from around the world. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 360 degree streaming project saw a 4,106% increase in views, and the Network of European Museum Organizations found a 70% increase in online presence in European museum websites in their COVID-19 report.

“Western art museums were not structurally meant to attract visitors from diverse backgrounds and cultures, but there is clearly a need and desire for more people to feel welcomed and inspired within gallery walls.”

Western societies have a lot of progress to make before our museum spaces can become as diverse, inclusive, and welcoming as the communities in which they serve. Structurally, the history of western art museums is one tailored to the recreation and desires of wealthy individuals, often with motives that have not historically reflected the best interests of the public. Museums have not historically been places to embrace and welcome mass and diverse audiences. Transforming the museum space to become one that welcomes and amplifies voices of communities that have been historically marginalized and overlooked will not be an easy task, and will likely call curators and art lovers alike to rethink how such sanctuaries can retain their sacredness while inviting new kinds of visitors into gallery spaces and exhibitions. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, this initiative has gained tremendous momentum as museums have been forced to rethink the roles that they play in society and the ways in which they can provide education, entertainment, and support to their communities.

As western countries slowly begin to transition to a post-pandemic society, museums have the opportunity to transform and update their collective relationship to the public. What this will ultimately look like and how long this agenda might last is unknown. Western art museums were not structurally meant to attract visitors from diverse backgrounds and cultures, but there is clearly a need and desire for more people to feel welcomed and inspired within gallery walls. It is safe to say that we are entering a new era of the museum in the 21st century. Only time will tell what this may be.