The Short-Lived Genius of the Germs

As tragically as their story ended, abrupt death may have been the only way for the Germs’ message to mean something.

SAMUEL HYLAND

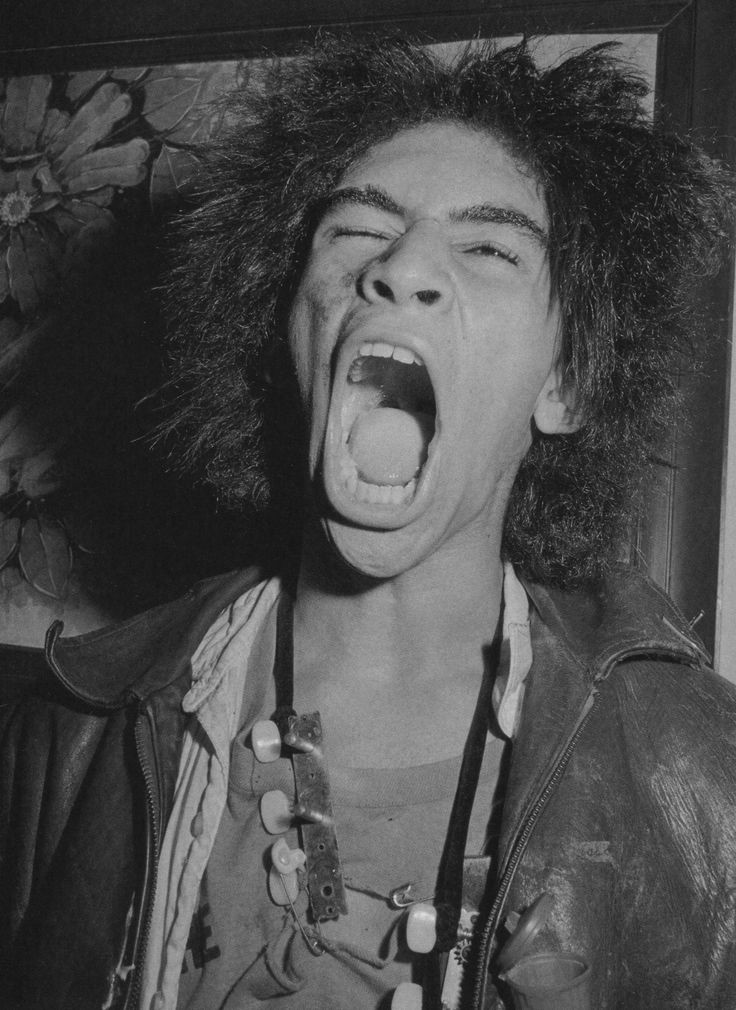

Darby Crash had an affinity for amateur mind control. Before the two would start performing together as a direct result of being kicked out of Los Angeles’ University Public High School for antisocial behavior, Crash and then-classmate Pat Smear had earned themselves a reputation for ringleading a mind-control operation directly in line with idols L. Ron Hubbard, Benito Mussolini, and Charles Manson. Crash, however, was the mastermind. He was a deceptive genius who got what he wanted by brute cerebral force, intimidating subordinates to the point where they believed themselves to be allies. It was common knowledge that Darby Crash could get anything he wanted. In Lexicon Devil, a Germs biography published in 2002, Paul Roessler, a childhood friend of Crash, recounted that he “had this natural power. It was either that he was so much smarter than anybody else… or he had techniques that he learned from the books he read or from IPS.” (IPS was a separate program housed within University Public High School, where root concepts of scientology were taught alongside other existence-oriented doctrines.) “Or he just had magic,” Roessler concluded.

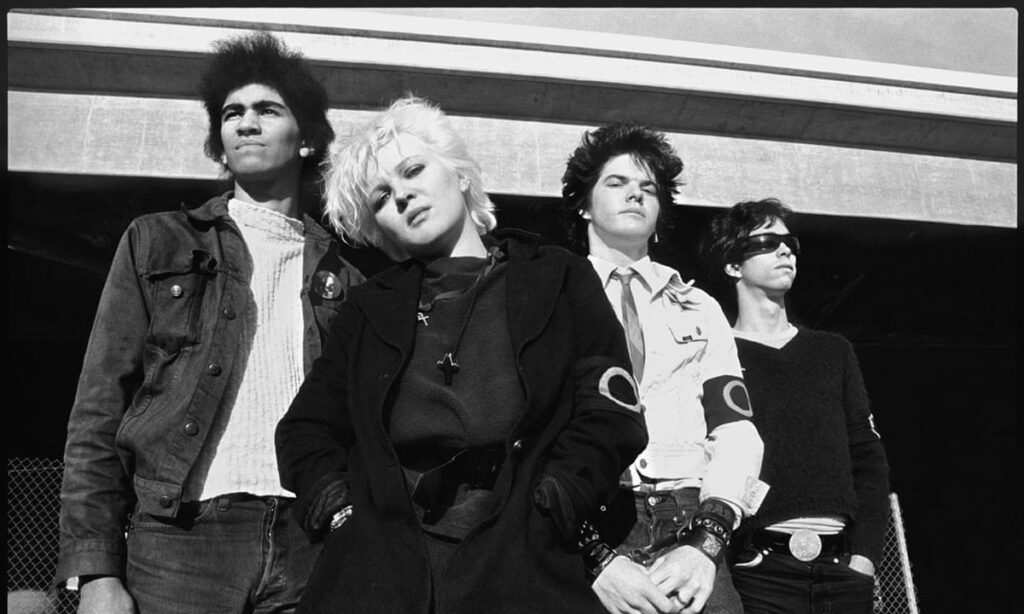

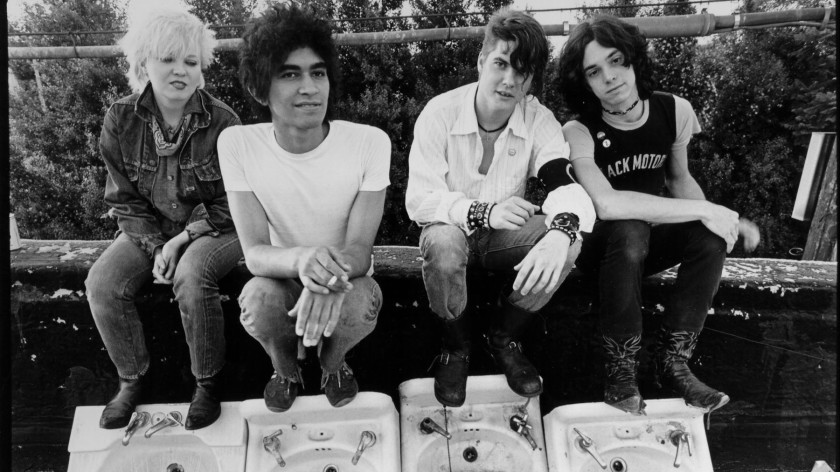

It was this mystical mind control that landed The Germs both their first concert appearance, and their first taste of radio airplay – neither of which came with as much as two single official songs to be accredited to their name. Their first proper gig was played in April of 1977 – at which point the band’s lineup consisted of Crash (then known as Bobby Pyn) on vocals, Smear on lead guitar, Belinda Carslisle on drums, and Lorna Doom on bass – after Crash had talked promoters into putting them on a bill with local acts the Weirdos and the Zeros. The show was not nearly as musical as it was chaotic. Crash emerged onto the stage wrapped from head to toe in red licorice. Group friends hurled spoiled food onto the stage. During an uninspiring performance of the Archies’ 1969 earworm hit ‘Sugar Sugar,’ members of the audience dumped the titular condiment onto the singer’s head. Microphones were dipped into peanut butter more deliberately than they were sung into. As far as their first radio appearance, much of the same brute energy, too: when The Germs released their first single, ‘Forming,’ in 1977, Crash called KROQ DJ Rodney Bingenheimer nonstop over the course of several days until he obliged to give them a slot.

“Records are only a medium to get something else done. . . I want to die when I’m done.”

The general artistic makeup of the Germs was one that waned minimalistic on actual music, and waxed paramount on surrounding energy. It is fairly easy, and very likely somewhat right, to reach the conclusion that Crash brainwashed all of the group’s followers just as intentionally as he had brainwashed his classmates prior to expulsion. (In one example Crash shared in an interview, himself and Smear had convinced a female classmate that he was God and Smear was Jesus. The classmate nearly suffered a mental breakdown). The hyper-focused surrounding culture the Germs had cultivated, even without the musical output such a response typically warrants, was cult-ish in more ways than one: their fans were affectionately nicknamed ‘Circle One” before they ever put out a record; their simple blue-circle emblem became the unofficial uniform of self-proclaimed band disciples; and, in perhaps one of the most far-out manifestations, Circle One members often identified themselves by burning circles onto their bare wrists with lit cigarettes – the scar left a grisly ring that donners dubbed “Germs Burns.”

As calculated as such ephemera comes off when witnessed up-front, much like its nucleus themselves, a greater deal of the actual substance resulted from a no-cares-given attitude that operated chiefly on the fly. The group’s original name, for instance, was “Sophistifuck and the Revlon Spam Queens,” but they wound up opting for the Germs out of two reasons – one of them being that “Sophistifuck and the Revlon Spam Queens” was too expensive to put on a t-shirt. Whether made up as a mask for the latter fact, or truly thought out behind the scenes, the second reason was very simply described by Pat Smear in the group’s first interview for Slash (the indie punk fanzine that inspired the cover of Whole Lotta Red): “We make people sick.”

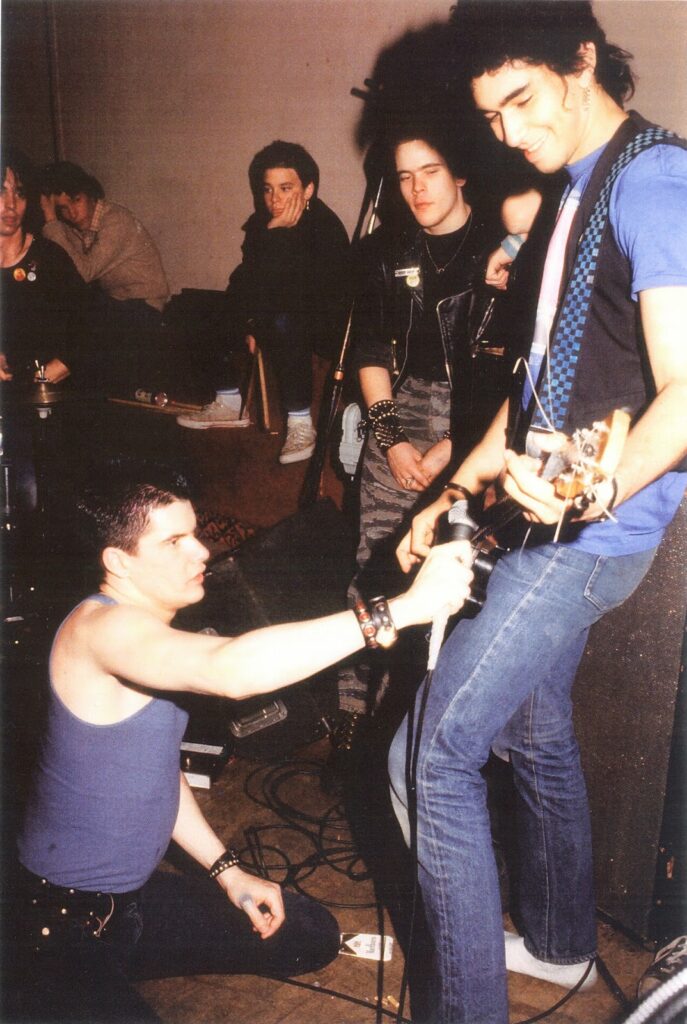

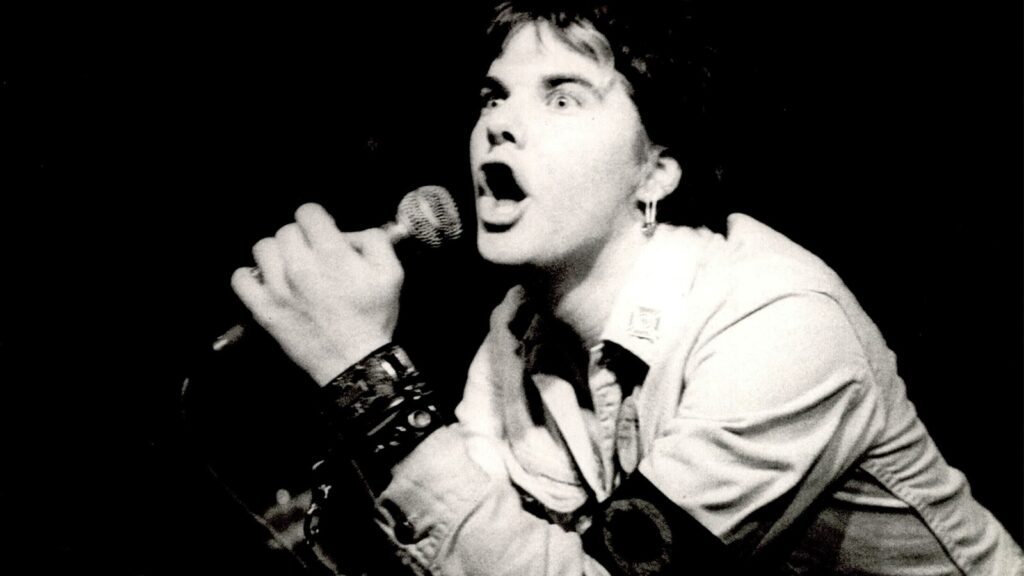

And make people sick they did. The typical Germs performance was not very far removed from their stage debut. Even as a band whose sole exposure, for a long time, was word-of-mouth that stemmed from a smattering of local gigs, it was commonplace for their material to test the limits of human tolerance. Crash often left performances bloodied, claw marks prominent on his bare chest, and rage seething in his eyes. Pat Smear’s guitar sounded more like an electric drill hammering away at a rugged, metal surface than it did an assemblage of six strings plugged into a speaker system. In the few interviews that they were featured in for both radio and print, they were brash and unfiltered, belittling their hosts and shamelessly fostering a reputation of self-righteous cretinhood.

In one on-screen question and answer session aired in The Decline of Westrn Civilization, a 1981 documentary about the era’s Los Angeles punk rock scene, Crash was asked by a journalist about the violent on-stage injuries he was known to subject himself to during performances.

“First I did it on purpose,” he said, nonchalantly fetching something from a nearby fridge. “To keep from being bored.”

The film then cut to Nicole Panter, the Germs’ longtime manager. “He’s come out of shows with huge scrapes and scratches and claw marks all over him, just pouring blood, but it always looks a lot worse than it is,” she said.

Asked to recount the worst instance of on-stage injury – also with remarkable nonchalance – he detailed flying down a flight of stairs directly onto a broken glass whiskey bottle. The injury required 36 stitches. He still played the show.

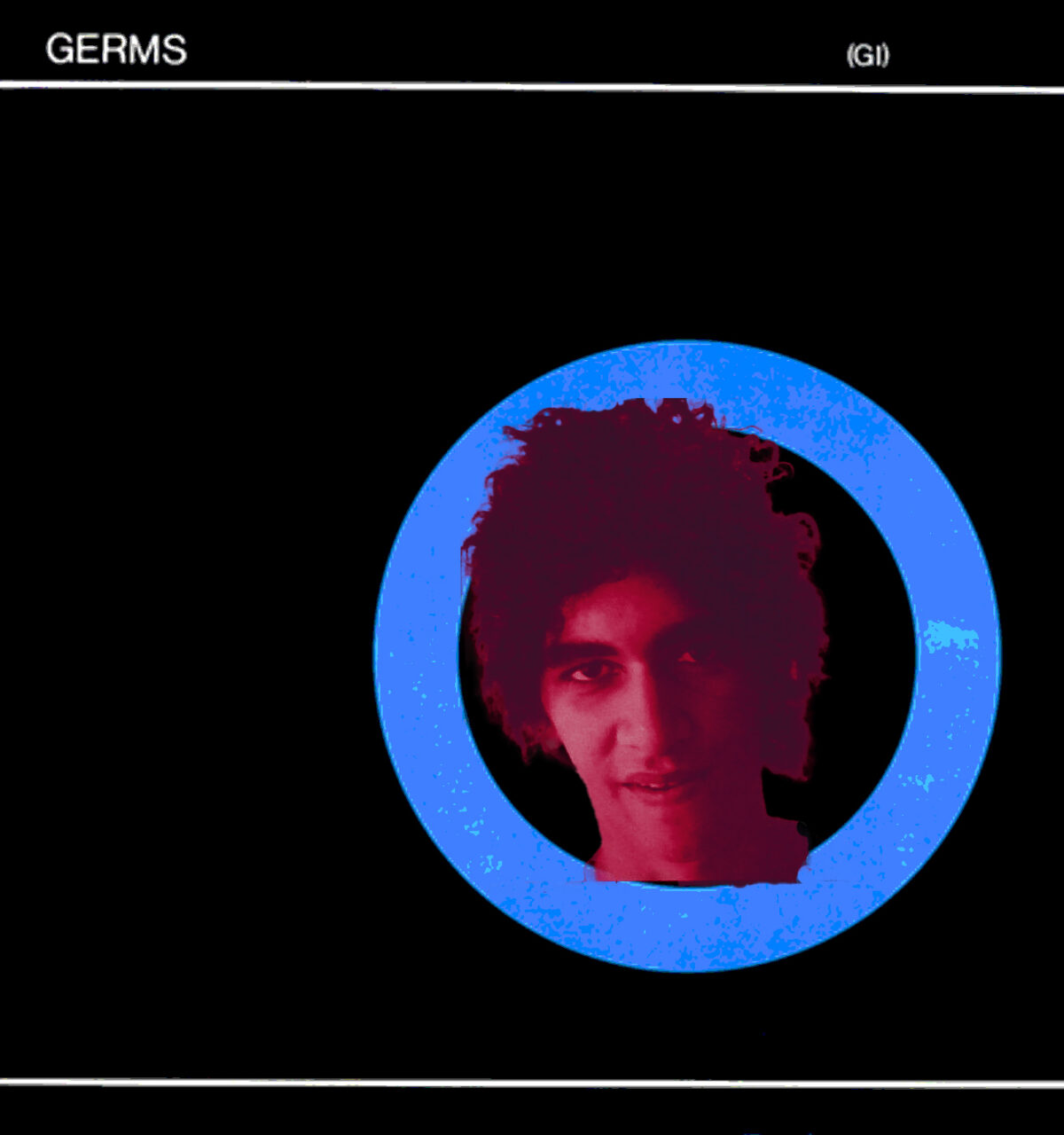

It’s a gruesome vitality that, even in the little music the group did record, continues to live longer than its creator. GI (which stands for “Germs Incorporated”), the first and only album by the band, was released in 1979 by Slash Records. Slash was the only label willing to accept the risk that came with delving into an unpredictable act like the Germs – not only were they pronounced the “world’s most volatile band” by writer Kickboy Face, but they had also proclaimed themselves “the worst band ever” without any shame in doing so. Still, though, there was potential radiated by their eclectic live act that perked the ears of Slash founder Bob Biggs, who quickly offered them a contract, commissioned punk legend Joan Jett as a producer, and purchased time in Los Angeles’ Quad Tech studios for the group’s recording use.

“I was a glorified babysitter, trying to get the sessions going,” Biggs recounted in Lexicon Devil. “Typically, I’d go over to Joan’s house and there’d be naked girls all over the place doing each other. Then I’d pick up Pat at his house over in West L.A. We’d get to the studio and Joan would pass out at the console and I’d have to wake her up and get her going.”

It’s anecdotes like these that illustrate just how impossible Biggs’ task was at heart: getting the Germs to record a full, polished, body of work was the equivalent of not only infiltrating, but subverting a punk culture that harped on entropy rather than calculation. Biggs’ undertaking is a puzzling one to truly visualize. There was genius, yes, in the unforgiving punk scene(s) of Los Angeles, but that genius only had energy enough to both live and die in the moment it was conceived. It was a flame that burned out, instead of fading away. Putting it onto a record would mean preserving it for years to come. But putting it onto a record would also mean having to squeeze juice out of a rock.

As much as GI may be conventionally unsuspecting at first glance – the sole LP released by a boisterous noise rock band that didn’t last any more than five years – it represents, in several ways, an impossibly clear snapshot of a target that never stopped moving. Not only does it bespeak the capture of lightning in a bottle, though: it sounds like it. ‘Communist Eyes,’ the album’s second track, blares through your speaker system with the kind of unforgiving blitzkrieg not far removed from the warfare of Crash’s totalitarian idols. Every audible instrument is just as loud as it is fast. You aren’t afforded much time to try to understand what any of it means before it’s over.

On ‘Richie Dagger’s Crime,’ too (perhaps the closest the Germs would ever come to pop music), Pat Smear’s guitar sounds far more like a mechanized torture instrument spraying out rounds and rounds of automatic ammunition, than it does a melody-making six-stringed apparatus. Alongside Smear’s chainsaw-esque power chord layering, newly-added drummer Don Bolles’ cymbal-heavy onslaught fosters a tangible intensity that makes one both desperate for it to stop, and far too hypnotized to press pause, at the same exact time.

With every song on GI, a never-changing constant is Darby Crash’s voice. His dialect of choice is a sinister growl of unintelligible chaos, dripping with thirst for amatuer mind-control, and shameless in its complete and total lack of hope for human understanding. Beyond his mayhem, yet, there existed much deeper meaning. “You didn’t know the words because it was all like ‘Warrrrrrrrwarrrwarr,’ when Darby’d sing them live,” John Doe, a vocalist for the band X, said in Lexicon Devil. “So everyone was just astounded when they got that first Slash record and actually read the lyrics. They were great!”

A great deal of Darby Crash’s genius took a backseat to his brash exterior; and the delivery of GI is a wholly accurate portrait of the career-defining dynamic: ‘Richie Dagger’s Crime,’ for instance, came off as anarchic yelling and screaming atop instruments that held equally little care for the listener’s hearing ability down the road – but at its thematic core, it was Crash’s Bowie-inspired autobiography, detailing his life as an underdog, and exulting about the arrogant resilience that kept it moving in spite of difficult odds. “I’m Richie Dagger / I can stomp and swagger / I can take on all your heroes,” the song’s opening lines read. “I’m Richie Dagger / I’m young and I’m haggard / The boy that nobody owns.”

“The construct produces a maddening dichotomy: either have a surplus of substance that goes undocumented, or have a surplus of documentation that lacks actual substance. There is little room for an in-between – and at either extreme, the fundamental problem persists: the movement will never be able to last as long as its energy demands.”

Reading between the lines on Crash’s lyricism also led one into darker crevices of his character. In ‘Lexicon Devil’ – the song that the biography was named after – Crash sneers, in white hot rage: “Gimme, gimme this, gimme, gimme thaaaaaaat.” The line, repeated on several occasions, paints a harrowing picture of his inhumane affinity for getting what he wanted. He wasn’t asking you to give it to him. He was telling you that you were going to do so. “‘Lexicon Devil,’ perhaps (GI)’s most iconic entry, repurposes Crash’s favorite manipulation device,” Pitchfork writer Madison Bloom wrote in a review of the album’s reissue. “The song was an admission of Crash’s thirst for supremacy, confirming that nothing he did was by accident.”

One of the compelling factors about GI is not the fact that it was released – although that is a feat in and of itself – but the all-too-realistic prospect of it having never come out at all. GI is often considered the first hardcore album, yet, once awakened to the realities of what it took to even get it on shelves, one is forced to wonder how long its respective subgenre churned unrecognized in the same bustling Los Angeles punk rock underground from which it emerged. It is then that GI becomes the first documentation of hardcore punk music, rather than the first instance of it. Much like the surrounding culture of the sound itself, the proliferation of rock-adjacent music that churned on over the end of the 20th Century was far more geared towards existing in the moment, than posturing itself to exist on tape. Emerging from a series of decades that saw firebrand, classic rock and roll redefine olden doctrines on a turf that was purely musical, this was a movement that was conversely, at the forefront, cultural. You didn’t have to make music to contribute to punk culture – you just had to be a punk. And, as revolutionary as such an approach was, it is the exact reason that we may not have nearly as much to show for that period as actually existed.

“To burn out, rather than fade away, was indeed the ultimate statement – but what if Darby Crash had achieved world domination within a five year period?”

For an era that was more or less defined by innumerable movements – some chiefly local, others nationwide, and all seeking to extract brand new extremities from a newly multi-limbed rock and roll zeitgeist – it was nearly counterintuitive that most so-called revolutions were not claimed by the champions themselves, but invented by journalists and spectators who had sought to make sense of what was inherently senseless. This was a murky period trudging along from the 1970s to the onset of the 90s, during which the dwindlings of genre-defining acts like the Beatles and the Sex Pistols carved gaping, unfillable holes in the musical niches they forged, leaving a smattering of upstart groups to make sense of the debris. Still, yet, making sense of the debris was not the outright intention – not too many post-(insert genre here) acts were striving to be “the next Beatles” – as much as it became an inadvertent side-effect of what the context bred. The brash, punk culture exhibited by many such acts was an epitome of the individualism that trumped all classification.

In one stark example, an obscure five-day festival held at a New York City gallery called Artist’s Space gave way to an equally obscure mini-scene of city-centric bands in the 1980s. The name under which the movement is remembered – “No Wave” – was not proclaimed out of outright pride, but annoyance by its carriers: in an interview with Roy Traken of the now-defunct New York Rocker, Teenage Jesus and the Jerks frontwoman Lydia Lunch sneered at the question of whether her group’s music could be considered “new wave.” “More like ‘No Wave’,” she scoffed.

Though it played out on a completely opposite side of the United States, the Germs’ brazen attitude was a seamless continuation of such an era-defining dynamism – too fast to declare its own meaning, but too meaningless to live very long once removed from its heyday’s incubation. Where the conventional formula for commercially successful output is more or less seventy-five percent music and twenty-five percent miscellaneous energy, the Germs flipped the entire equation onto its head. Their own makeup, rather, looked a lot more like ten percent music and ninety percent antics. And still, they arrived at the correct answer.

It is a feat that proves more and more difficult to accomplish in the internet era. As streaming services pose increasingly threatening pressures for artists to channel their work into consumable, web-friendly packages – even if subscription to such a structure is against the creator’s values – the possibility of being remembered without tangible documentation to show for oneself becomes more wishful thinking than reality. There are several instances to be pointed to in which artists who may have emerged from one commercial framework quickly had to adapt to the newest manifestation. In one case, Gucci Mane, a rapper who rose to prominence in the mid-aughts, fielded a lengthy string of imprisonments in the 2010s. Over the course of his time spent behind bars, remaining relevant was a rising concern: one his label responded to by releasing 85 albums in 2015 alone.

The dynamic is also evidenced by a recent rise in posthumous releases. Though always the subject of controversy, the issue is one that has taken tangible rise within the past decade, with less-than-favorable records being put out by the estates of late acts including Juice Wrld, XXXTENTACION, and Lil Peep. The latest in a lengthy list of suspects is Faith by Pop Smoke, the slain New York rapper who promised remarkable potential with his grisly intonation. “Though it’s hard to be optimistic, there’s a long history of shameless, money-hungry posthumous albums; and now, after a tragic couple of years in rap, a new generation of fans is being terrorized and exploited for their streams,” Pitchfork critic Alphonse Pierre said in a review of the record. “Where will we draw the ethical line? How far are we from the days where it’s commonplace for labels to put on hologram live shows and pay some tech company to recreate a voice? Faith is a bleak reflection of the reality that nothing is off-limits if it will help record labels pocket a few more dollars.”

There does exist, however, a small window of chance for an approach like that of the Germs – less music, more energy – to successfully build a culture removed from the clutches of the studio. London hip-hop supergroup Neverland Clan, for instance, rose to prominence not from an impressive discography, but from a chaotic live act that garnered thousands of turmoil-seeking followers. “We were a group that were really bringing that punk energy back to the black community,” group co-founder Ryan Hawaii told Sammy’s World in an interview. “Like mosh pits and shit. Jumping in the crowd. That kind of shit wasn’t going on in London – I mean, obviously rock, of course – but not in a hip-hop space. We were pioneers of bringing that energy to fame.”

Neverland Clan would go on to make waves violent enough to reach the likes of Lil Uzi Vert, Playboi Carti, and Virgil Abloh – but as arguable as it is to make a case for their legacy, one can say just as defensibly that it never existed. The most damning piece of evidence is the lack of it: Neverland Clan did not record any music, at all, during its brief time as a faction. It exists principally in memory, and its impact varies depending on who you ask. That is, assuming that the person you ask happens to remember.

A common grievance in surrounding communities is that punk culture is dead; and very much so, its primitive essence is. The commercial climate that groups like the Germs rose amidst was, unlike that faced by acts today, free of the pull to prioritize documentation over tangible substance. The current construct produces a maddening dichotomy: either have a surplus of substance that goes undocumented, or have a surplus of documentation that lacks actual substance. There is little room for an in-between – and at either extreme, the fundamental problem persists: the movement will never be able to last as long as its energy demands.

🎸 🎸 🎸

For as much of Darby Crash’s genius that was smothered underneath layers of intimidating hostility, one of the most crystal clear images of it came in a precise goal the frontman set years before the Germs would reach their peak. “Five years, beyond the song itself, marked a passage of time that meant something to Darby,” said Don Bolles, the Germs’ drummer, and author of Lexicon Devil. “The Chinese Communist Party had their five-year plan, Bowie sang about it and Darby figured if he hadn’t achieved world domination by then, why bother? So after five years he sort of had to put up or shut up.”

Darby Crash was undeterrably intent on achieving a cult of personality – literally – within a period of no more than half a decade. And whereas such a plan comes off as promotional shock value for most, for someone with Crash’s distinct prowess for mind control, it was completely and totally within range. It was the reason why, without having a single official release to their name, the Germs were able to play enough shows in Los Angeles to cultivate a bubbling subculture, get their music on the radio in the midst of an overcrowded rock movement, and perk the ears of a prominent label owner who would get them to record one of the most influential records of their genre’s lengthy history. There were no suit-and-tie clad businessmen running around behind closed doors to strike up deals with A&Rs and local promoters. Rather, it was Crash, annoying executives with nonstop phone calls, intimidating organizers into putting his band on their setlists, driving people crazy enough to give him what he wanted. All because he had a plan – and it was supposed to take no more than five years. If that much.

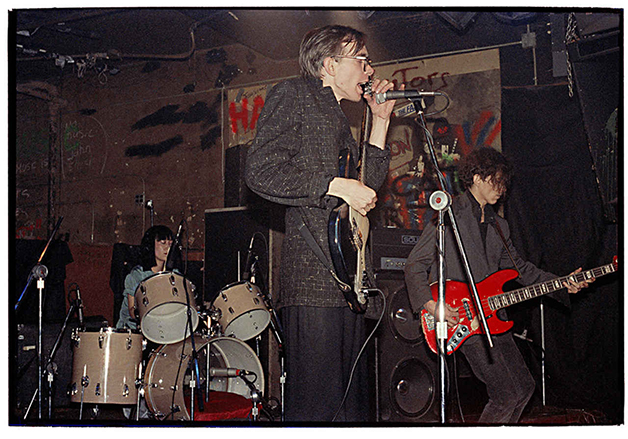

But, as fate would have it, the Germs themselves would not survive for that long, let alone provide solid leverage for Crash to achieve domination of planet Earth. Following the release of GI, Crash grew fed up with Bolles over a growing conflict between the two, and fired him, enlisting close friend Rob Henley as a replacement. The band broke up shortly afterward. It was at this point that Crash, much like Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols, sought to redeem himself with a self-centric second act: in 1980, he formed the short-lived “Darby Crash Band” alongside Smear, Circle Jerks drummer Lucky Lehrer (who joined a day before their first live performance), and bassist David “Bosco” Danford. That group, too, split up in less than a year.

“We did this show so you new people could see what it was like when we were around. You’re not going to see it again.”

Crash reached out to Smear about doing a Germs reunion show, citing that it was necessary to “put punk into perspective” for newcomers who had emerged onto the scene in their absence. Smear agreed. The Germs’ final performance – with Bolles back on drums – took place in front of a sold-out crowd at the Starwood nightclub in Los Angeles, packed to the brim with kids who marveled at the group’s unparalleled energy. Although Crash had told Smear, prior to the show, that “The only reason I’m doing this is to get money to get enough heroin to kill myself with,” many members of the band were confident that this was the start of a permanent reconciliation. After all, Smear would later recount, Crash had made similar threats so often that they came off as macabre humor.

“We did this show so you new people could see what it was like when we were around,” Crash said, shortly before the gig was over. “You’re not going to see it again.”

Four days after the performance, on December 7, 1980, Crash took the money he had earned from the event – $600 – and overdosed with its worth in heroin. He was 22 years old. The overdose had been part of a suicide pact he previously arranged with close friend Casey “Cola” Hopkins; but in an unplanned turn of events, Hopkins ended up surviving – she discovered Crash’s lifeless body laying beside her upon coming back to consciousness.

As tragic as Crash’s death was, one of the most harrowing – yet career-epitomizing – developments that surrounded it came in its timing. Just one day after Crash overdosed, a man named John Lennon was gunned down by a deranged fan in New York City. Crash’s suicide was predictably overshadowed by the demise of a much larger cultural figure: even his local paper incorrectly reported that he had died as a result of taking too many sleeping pills.

The overshadowing of Crash’s death was eerily in line with the secretive genius he often hid behind his mayhem; and, right in line with such a construct, there were several things that even his closest friends would not learn until after his passing – including his sexual orientation (Crash only came out as gay to a very small circle of family and friends). Most stark of all the unknowns, yet, was what else he had to say. To burn out, rather than fade away, was indeed the ultimate statement – but what if Darby Crash had achieved world domination within a five year period? Much like the movement he championed, there are no periods – only question marks.

The Germs were a band that took their “underground” labeling to heart: not only were they underground in the sense that their corresponding scene happened to function under that title, but they also existed, almost intentionally, purely removed from the canon of accepted American music. (They did not produce enough ephemera to be accepted, and the little ephemera they did produce was unacceptable). It was in this way that they not only embodied underground culture, but epitomized it. To be underground is to live at the submerged portion of the iceberg – picture it as the popular “deep web” diagram that your elementary school teacher may have shown you in computer class. At the tip of the glacier lay all artists that officially exist on record – whether by way of extensive discographies, smatterings of EPs here and there, or singles that stand as lone representations of decades’ worth of work. Buried underneath the water, oppositely, are the far more extensive catacombs of acts that do not, in fact, have any form of legitimate documentation to prove that they were ever real. The shallower portions may hold versions of artists that are known to exist, but just not on the commercial plane – maybe the Kanye West that made Turbo Grafx 16, the youthful A$AP Mob that produced Lords Never Worry, or the many Playboi Cartis that scrapped original Whole Lotta Red versions to ward off leakers. The water gets darker as proof of existence wears thinner. And by that metric, the Germs spent most of their careers – very likely all of it, had Biggs not intervened – at the ocean floor.

GI coming out was the equivalent of a fisherman reeling something in from the very bottom of the sea. Like most deep-sea life (of the few species we have actually discovered) that exists at the ocean floor, the Germs were most known for their effervescent features, hostile mannerisms, and strange makeup in comparison to the rest of the world. What this appeal does, though, as cool as it makes their case, is push the important pieces of their message right back down to the pitch black underground from which it rose. It’s very aesthetic becomes the anchor weighing it down.

“It took years for Crash to be widely recognized as a gifted writer, but his work took on a new life after his ended,” Bloom wrote in the aforementioned GI review. “Germs had an immediate impact on their L.A. peers, but their contributions were particularly felt in the following decades, when artists like Hole, L7, Melvins, Henry Rollins, Meat Puppets, and Red Hot Chili Peppers cited the band as a major influence.”

Although the Germs burned out quickly after reaching their highest point, their footprint, as implied by such a lengthy list of brainchildren, far outlasted the confines of their brief life together. Smear currently plays rhythm guitar for the Foo Fighters; Bolles has performed in a lengthy list of acts; and Shane West, a replacement of Crash in later reunions, portrayed the late frontman in a 2007 biopic called What We Do Is Secret.

The mystic legacy they have maintained in punk circles, along with the fact that they influenced as much as they did, tacks yet one more question mark to their rough-edged story: what if the Germs had faded away, rather than burn out? It’s a challenging image to conjure, given the band’s die-hard nature: picture them, instead of dramatically falling apart after one fully-realized project, putting out album after album well into the following decades, for a fandom that grew just as small as it was separated from the remainder of the American musical canon. Yes, to exist outside of the lens of mainstream appeal was right in line with the Germs’ careless gospel. But, even as tragic as their end was, it becomes clear that abrupt death may have been the only way for their message to mean something.

“Records are only a medium to get something else done,” Crash said in Lexicon Devil. “. . . I want to die when I’m done.”

As it stands, we only know the reality of one side Crash’s statement exudes: we understand very well, unfortunately, what it looks like for Crash to die when he says he’s done – but what could the “something else” he was striving for have possibly been? Even though GI registers to consumers as a focused project that was a priority, rather than a standby for something bigger, both the quote and Crash’s all-around intense nature paint a picture of a much grander mission, terrifying in its possibilities, and stirring in its incompleteness.

All of what Darby Crash could have become lies in who he was. And, for that matter, a majority of who Darby Crash was lies within who he idolized: L.Ron Hubbard, Benito Mussollini, Adolf Hitler… you get the point. But it wasn’t so much for their questionable ideologies that he gravitated toward that crowd, as it was for their mastery of the mind control he so wished to someday dominate the world with. Hubbard pocketed millions of dollars from a self-created religion that harped on infiltrating the mind’s very inner workings (“You don’t get rich writing science fiction,” Hubbard famously said. “If you want to get rich, you start a religion”). Mussolini perfected the totalitarianism that would define some of humanity’s darkest decades. Hitler used his cerebral control to commit the most dreadful form of extended mass murder known to modern mankind. Darby Crash saw inspiration from such feats, rather than the disgust they naturally first conjure. If savviness for mind control was the price of world domination – and they could do it – why couldn’t he?

“These are questions that, in direct line with their short-lived emulators, will die unanswered. They are two of an infinite pantheon of what-ifs. There is no way to generate accurate responses but to have been there.”

For someone who so passionately believed in his ability to control the world (in five years, too) that he killed himself when he failed, the possibilities of what he could have turned into, had the “something else” been actualized, are far more unsettling than they are delightful. Had Darby Crash not been exposed to a brewing punk-infused landscape to channel his psychic energy into – perhaps if he had grown up in another country, or maybe even just another region of the United States – the canon of his ceiling likely goes, very quickly, from legendary punk rock pioneer, to on-the-loose mind control specialist with endless reign over a rapidly-expanding sphere of influence.

In one anecdote shared in Lexicon Devil, fellow Los Angeles punk rocker Rick Elerick attested to the puzzling mental makeup of Crash, and the effect it had on him long-term. “He taught me to question everything, and to totally look at reality, not to accept everything, and to make up my own mind. (…) He did it for everybody he came in contact with,” he started. “Sometimes Michelle Baer and I would talk about Darby when he wasn’t there, and Michelle would wonder aloud if he knew what we were saying about him – whether he had some sort of telepathic powers, because the power of his mind was so overwhelming. I once thought, ‘Maybe he really does know what we’re thinking.’”

Sometimes, as much as Crash’s mental dominion appeared to carry an eerie benevolence at points, its narcissistic, dictatorial ambitions shone through the cracks. Alice Bag, for instance, is a legendary frontwoman of the same LA punk rock underground from which Crash emerged. The two often had long, intellectual conversations surrounding the weight of being looked up to by a vast number of people. They frequently disagreed. Whereas Bag thought that the proper way to interact with one’s followers was to treat them as respectable peers, Crash believed that it was to assert oneself clearly and dominantly as a superior. “It used to really bother me that Darby enjoyed trying to control people,” she said, years later. “I felt it was demeaning not only to his followers, but to himself. It used to bother Darby that I treated my fans as equals. He would lecture me on what people expect in a leader.”

And what did Crash think people expected in a leader? “Darby definitely wanted to make his presence known – he wanted to be the guy,” journalist Tony Montesion said. “He wanted to tear the whole structure down, point a finger at a guilty nation, and then for him to be the new main man – he was narcissistic like that.”

Darby Crash, in nearly identical fashion to the hardcore punk culture he represented, did not have to make music in order to turn ordinary people into subordinates. The effects of his psychic powers have been felt by everyone from close confidantes to awestruck audience members, and the remorse he felt for any and all damages caused was miniscule enough for his mentality to take him terrifyingly far in the global dominion he craved.

But the opposite end of his story – the one that makes it the most interesting – is, again, that there was a good chance of us never even knowing he existed in the first place. We only know that Crash, a man with psychic superpowers and an intensity that built a subculture from the ground up, was real, because Bob Biggs just so happened to be in attendance at a show of his. In a way, such a reality is just, because he was the frontman of underground culture’s epitome – it would only make sense that he himself would exist at the bottom of the iceberg, too. Yet, look at it from another angle, and his story becomes maddening to think about. If Darby Crash was a superpower-wielding tragic hero who looked up to dreaded totalitarian figures, and we only got lucky enough to know he existed because a label exec took a chance – what supervillains may live in my area? How many of them have world domination at the top of their bucket lists? And how many times have I gone from ordinary person to devoted subordinate?

As of the publication of this piece, the Rolling Loud festival is well underway in Miami, and there is a growing sensation that we have emerged from the darkest parts of our disease-ridden tunnel and finally begun to see the light. Venues are opening back up, and in grand fashion, too – in New York, one month ago, Madison Square Garden opened its doors for what had been the first time since the pandemic’s inception: in front of a sold-out crowd of fully vaccinated fans, among other things audience members were a year removed from, Dave Chappelle jestingly sang Radiohead’s ‘Creep’ while the Foo Fighters played their instruments in the background. Exactly one month before that, the New York Knicks had defeated the Atlanta Hawks in a first round playoff game in front of 15,000 fans – the largest indoor gathering in New York since the start of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

“What if, when Hitler was rejected from the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, instead of channeling his anger into state-controlled genocide, he channelled it into a guitar amplifier? What if, instead of doing so via a self-invented dictatorial religion, L. Ron Hubbard satisfied his desire for money with a gritty hip-hop mixtape?”

With the return of mainstream culture, grander than ever before, also comes the return of the underground. And as the culture at the tip of the iceberg begins to bolster more and more – the depth of its basement simultaneously deepens. Yes, there are likely local musicians with superpowers in your neighborhood; yes, there is probably an extensive undercover mind control operation churning on your very block; and yes, both you, and possibly everyone that comes after you if a label exec doesn’t turn up to a specific show, are blissfully unaware of either entity’s presence unless you have witnessed their respective vitalities with your own two eyes.

Unlike the case of the Germs, however, the opportunity still exists for you to be there for the lightning – even if no one happens to catch it in a bottle. You can go to that show. You can hang on to that flyer the snapback-clad dude by the subway station forces into your hand every time you walk past him. You can make that right turn on your way home and check out the noise by 36th street.

What you cannot do, on the contrary, is come to an understanding of the opposite of Crash’s dynamic: Crash represented a punk rock pioneer destined to become a totalitarian leader – what if totalitarian leaders became punk rock stars instead? What if, when Hitler was rejected from the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, instead of channeling his anger into state-controlled genocide, he channelled it into a guitar amplifier? What if, instead of doing so via a self-invented dictatorial religion, L. Ron Hubbard satisfied his desire for money with a gritty hip-hop mixtape?

These are questions that, in direct line with their short-lived emulators, will die unanswered. They are two of an infinite pantheon of what-ifs. There is no way to generate accurate responses but to have been there.

Right now, though, as we ease back into our cultural ebb and flow, an opportunity many Germs devotees continue to wish for sits in our collective palm: to answer these questions before they have to be asked. And – especially without the threat of grinning cigarette-toters coming over to burn circles onto our wrists – the door is open wider than ever.