SAMUEL HYLAND

A year after the Civil Rights Act purported to solve America’s most imminent domestic problem, tensions abroad quickly put out what light remained at the end of a long tunnel for society. On August 18th, 1969, though, the ghost of such hope was conjured by what had extinguished it in the first place: ear-splitting, brain-melting, torpedo-blasting pandemonium. From the fingers of a black Native American, the Star Spangled Banner emanated in a war-torn reality masked by the empty promise of justice for all.

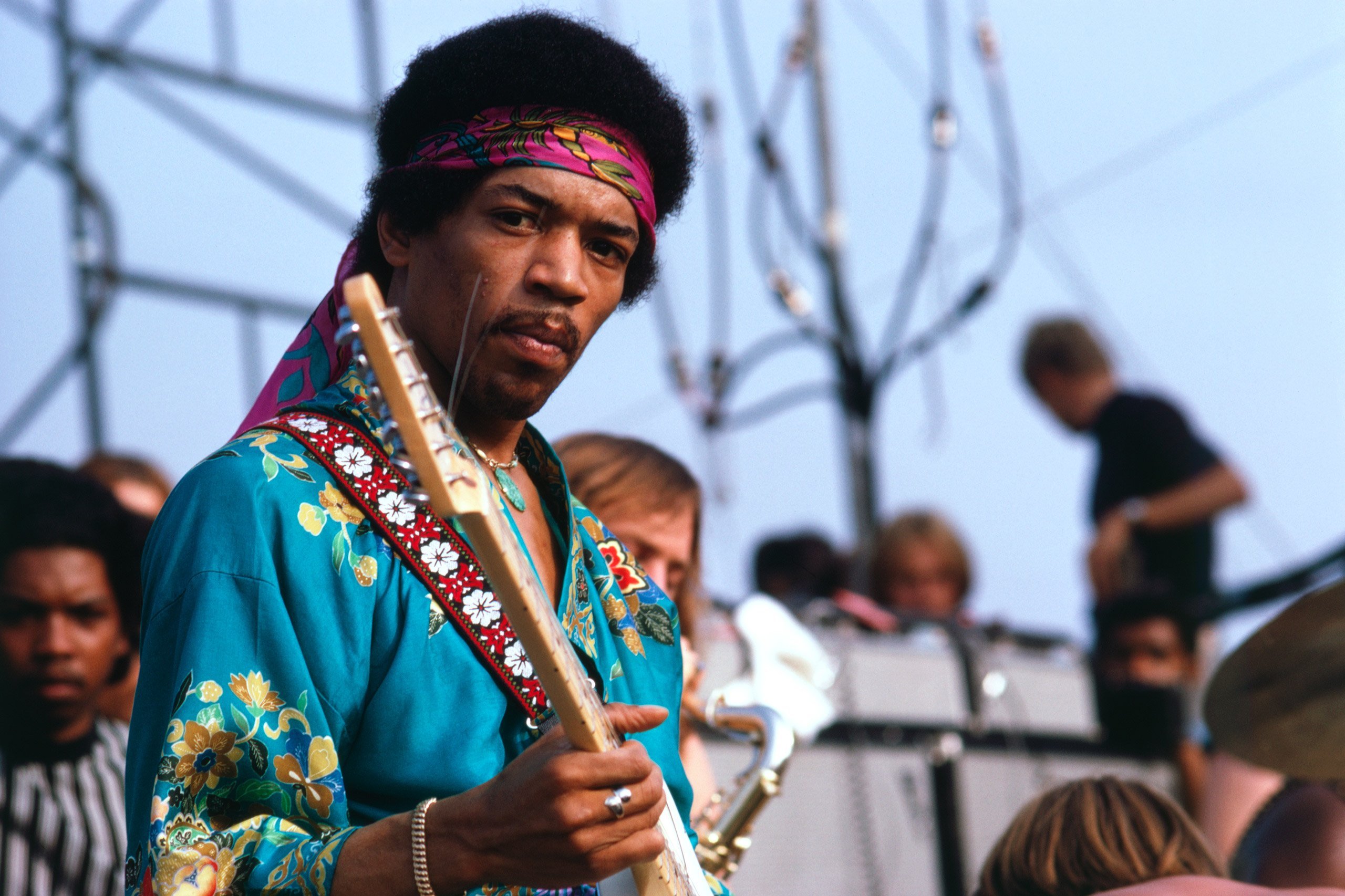

Counterculture is generally defined as a lifestyle opposed to prevailing social norms. In decades prior to the aforementioned, allegiance to the flag took shape as a prerequisite for citizenship – but, a rising cultural wave apexed by 1969’s Woodstock festival made it further evident that the opposite was possible. Jimi Hendrix was the last act to take the stage. The national anthem was far from the first song he played.

“I thought it was beautiful,” he mused in a subsequent appearance on the Dick Cavett Show.

Though the question of whether or not it was arose from the warrish manner in which it was played, it applied universally in that America had spent the past year asking itself the same thing: Is there beauty within resistance? Over the previous decade, the answer pointed further and further towards an affirmative.

Just a year before Woodstock, 1968’s Democratic National Convention – one of two annual events serving to celebrate U.S Democracy – culminated in what was dubbed by various media outlets “a police riot” in response to protests against the war overseas. But it was beautiful. It was “our energy, music, politics, school, religion, play, battleground, and our sensuality,” Abbie Hoffman wrote in Woodstock Nation (1969). Militance grew into the mainstream; narratives quickly slipped out of the government’s control.

As for Hendrix’s performance, though, melody (or lack thereof) was not the only element questionable. The guitarist did not reserve the anthem for an opening standardized by sporting events, school districts, and other performances nationwide – within a few minutes of playing it, he was walking off the stage. Chords were supplanted by chaos, riffage was superseded by rebellion. Patriotic certainty was challenged by the question mark that is revolution.

Hendrix briefly added to the dialogue before moving on to Cavett’s next question. “It’s not unorthodox. I’m American. So I played it.” There was no legitimate incentive to any patriotic act on that day. Before him – both figuratively and literally – promises of freedom, peace, and harmony symbolically crumbled in the drudgy muds of indiscretion and infidelity. But he was American. So he played it.

The rendition was forthright in its flaws, and that was more of a suggestion to America than a serenade.