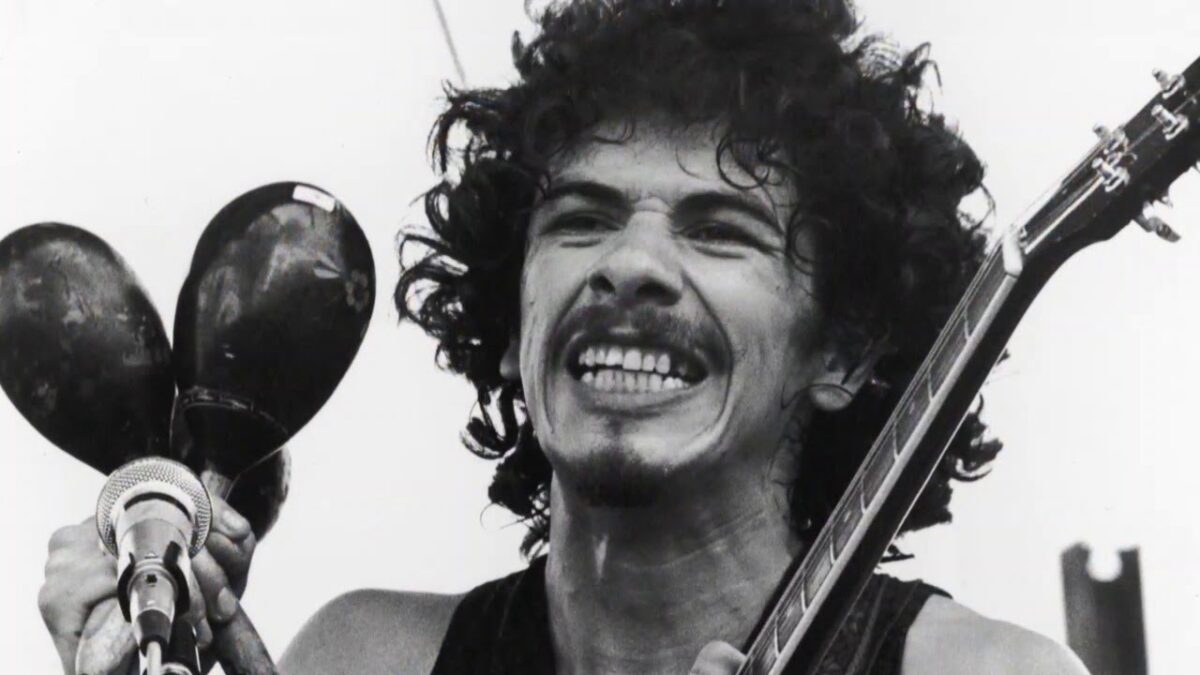

How drugs and music can give birth to the highest of highs – and the lowest of lows. ABOVE: Carlos Santana performs at Woodstock (1969). He was so high on acid, he said, that he spent the entire set wrestling what he thought was a live snake. It was his guitar.

SAMUEL HYLAND

“Tabby began by dumping a trashbag full of stuff from my office out on the rug,” Stephen King recalls in his 2000 memoir On Writing. The list ensues: “Beercans, cigarette butts, cocaine in gram bottles and cocaine in plastic baggies, coke spoons caked with snot and blood, valium, Xanax, bottles of Robitussen cough syrup and NyQuil cold medicine, even bottles of mouthwash.” Just months prior to the above intervention, King published Tommyknockers, a forties-style novel on alien creatures that occupied the mind of a host, providing an uncanny sort of superficial intelligence. But, he wrote, your superpowers were not free of charge. What you gave up in exchange was your soul.

Narcotic tommyknockers are no prerequisite for artistic output. Yet, for the many who have made the sacred transaction, it is a common testimonial that allowing visitors into the mind awakens a third eye. It is through this edifice that impossibility makes its exit – a process we’ve dubbed psychedelia – wherein the chords are fuzzier, the voices are slurrier, the real and fake are indecipherable. But there is also a new sense of hyper-consciousness. Are we bound to the limits of our natural ocular? Or are we allowed a glimpse of what the artists perceive, a survey of their world from its stratosphere?

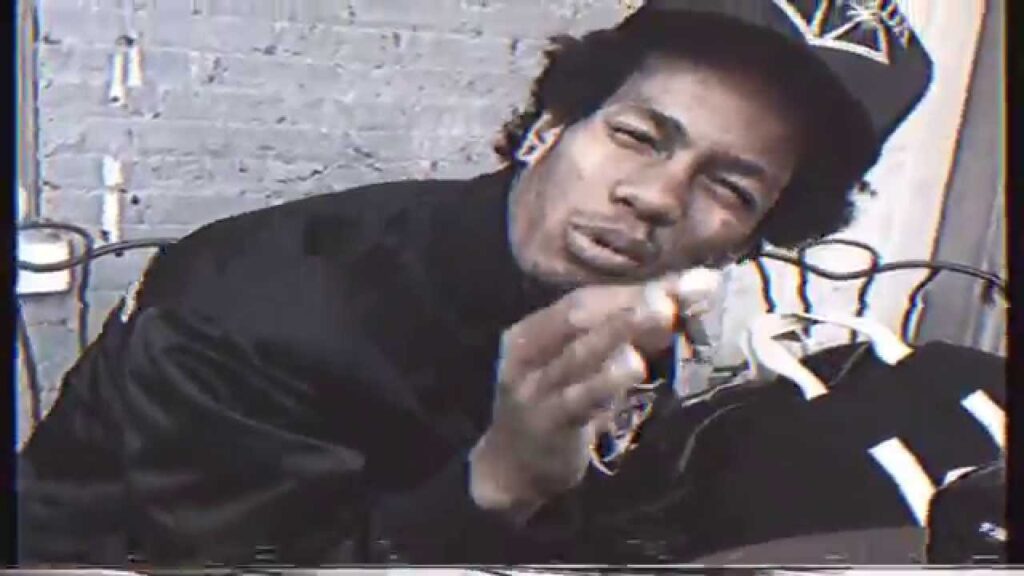

Chris Crack is one of these otherworldly fantasists. In just five years, the Chicago MC has already released sixteen studio albums, most of which were manifested in the spur of the moment (“Sometimes I just wake up some morning like, I’m dropping an album,” he told Billboard). His down-to-earth vibe emanates from blunt song titles – Overthinking Kills Happiness; Imagine Not Being Black; Hypebeasts Ruined Bape – down to the lyrics themselves: “I’m sorry it’s past tense / he just wanna be successful / that’s why he don’t have friends / and being woke ain’t fun” (God’s Ghostwriter). Chris Crack’s universe is one of oversaturated color, infinite possibilities, a complete absence of wrong answers. It’s an eternal amusement park that was exclusively paid for by his letting in of the tommyknockers.

Over a Zoom call early one Friday morning, we talked about this relationship, know-it-all white people, and various other things. I asked him how drugs informed his output over time. The answer was blunt.

“I just stopped giving a fuck,” he said.

“I stopped giving a fuck about what are they gonna think? What are they gonna say? What are they gonna feel? You would never know anyway – so what’s the point of trying to overthink that shit?”

Born Christopher J. Harris, the rapper’s first encounter with drugs came after a sixth grade school day, accompanied by one close friend. His eyes expanded as he walked me through it. “It was intense – I couldn’t enjoy it like I wanted to.” He burst into a knowing chuckle – the kind of Snoop Dogg-esque guffaw that radiates years of being on some swag shit – before narrating further. “Shit was craaaazy. I came home, I had the munchies; my mom was home, I thought she was going to notice.” But, alas – “she ain’t notice though!”

Music entered Harris’ life via a white friend of his by the name of Cutta. It was at Cutta’s house, he told Billboard, that regular access to a state-of-the-art studio elevated him from casual rhymes barred by overthinking, to boisterous bars based completely off of fucks not given. I asked him when he initially connected the dots between music and drugs — he answered, with a grin: “When I found out smoking makes you think of some wild ass shit.”

It’s exactly what manifests itself in his music: wild ass shit. On Joy More Important Than Success, he spits a gritty testimonial of the grind to stardom; it’s packed with imagery ranging from puppies in pizza boxes to sweethearts from Van Nuys, over a soulful gospel sample originally performed by Sonya Barry in 1993. Listening to it makes one feel the need to apologize. The transgression? Nothing avoidable. There comes an inevitable nakedness with not being on Chris Crack’s wave.

A similar dynamic is at play in Everything You Imagine is Real, the fourth track off of his 2018 project. “I hate leaving my friends ‘cause I gotta be alone with my thoughts,” he admits in the opening bar. By the fade-out, we hear of breakfasts at Fresno’s, dodged kisses, and doubling back to wind up ‘popping like bubble wrap.’

It’s a steady fusion of narcotics and melodies that formulates Chris’s wizardry in the studio. He works the formula like a mad scientist; the latter the variables, the vibes the product.

“I have all this music piled up, man,” he told me. “There was a point where I just said fuck it, I’ve gotta get this shit out.” (Literally – he revealed to me later in our interview that he has another album coming out within the next two weeks). Drugs have given Harris the swaggerous kind of prideful confidence that doesn’t need a major label to tell it where to go, the kind that, in a sarcastic, sing-songy pitch, permits him to declare of firms like Def Jam: “we live in a time now that we don’t neeeeed ‘em!”

But not all drug-influenced occurrences are memorable. One day, while driving on mushrooms, he was pulled over by police. There were more shrooms in the vehicle, and little time remained before the cops would approach his front window.

The officer pulled up. The drugs were gone. The garbage is not where they went.

“I was in that (jail cell) tweakin’ out. And it wasn’t good, because, you know, I want to feel good. But you could just feel people’s negative energy – you could just feel everything, and it ain’t cool.” In the silence preceding my next question, his smile faded.

Yet, good and bad trips behind him, Chris Crack has his eyes set on continuing to refine the artistry he’s worked on for the past five years.

“You can laugh to my shit, cry to my shit, ride to my shit,” he explained minutes before we wrapped up our chat. “I just want you to see this picture I’m tryna paint.”

The music industry overflows with minds like that of Mr. Harris, where tommyknockers coexist with sound to conceive boundless caverns of alternate realities.

Perfected versions of the formula encase experiences within vinyl sleeves. Acid Rap, Maggot Brain, Electric Ladyland. They are exclusive tickets to the warped worlds of boggled brains, voyages far, far away from the realities we have all at some point yearned to escape.

But sometimes the tommyknockers invite their friends. They overtake the music, then the mind.

And soon after, the party is over.

In a 2019 article for the Source following the death of Juice Wrld, Zoey Zorca outlined the deadly dangers of music’s constant flirtation with drug culture.

“While many rappers have openly stated that their reference to drugs is as much a part of the rap game fantasy as violence and other illegal activities,” she wrote, “in recent years, far too many rappers have succumbed to the drug culture rather than keeping it a part of their art. The hip-hop community, like all, is not immune.”

Hip-hop is a constant party. The genre embodies a long-disgraced culture of life with a disco ball overhead, practicality thrown out of the window for an eternal banquet of vivid being.

It is in this sense that New York embodies hip-hop culture. Along the moonlit summer streets of Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx, one may find that the parties come in the same manner as the ant infestations: endless, stopped only by force, annoying as shit to Mr. Cartwright from down the hall.

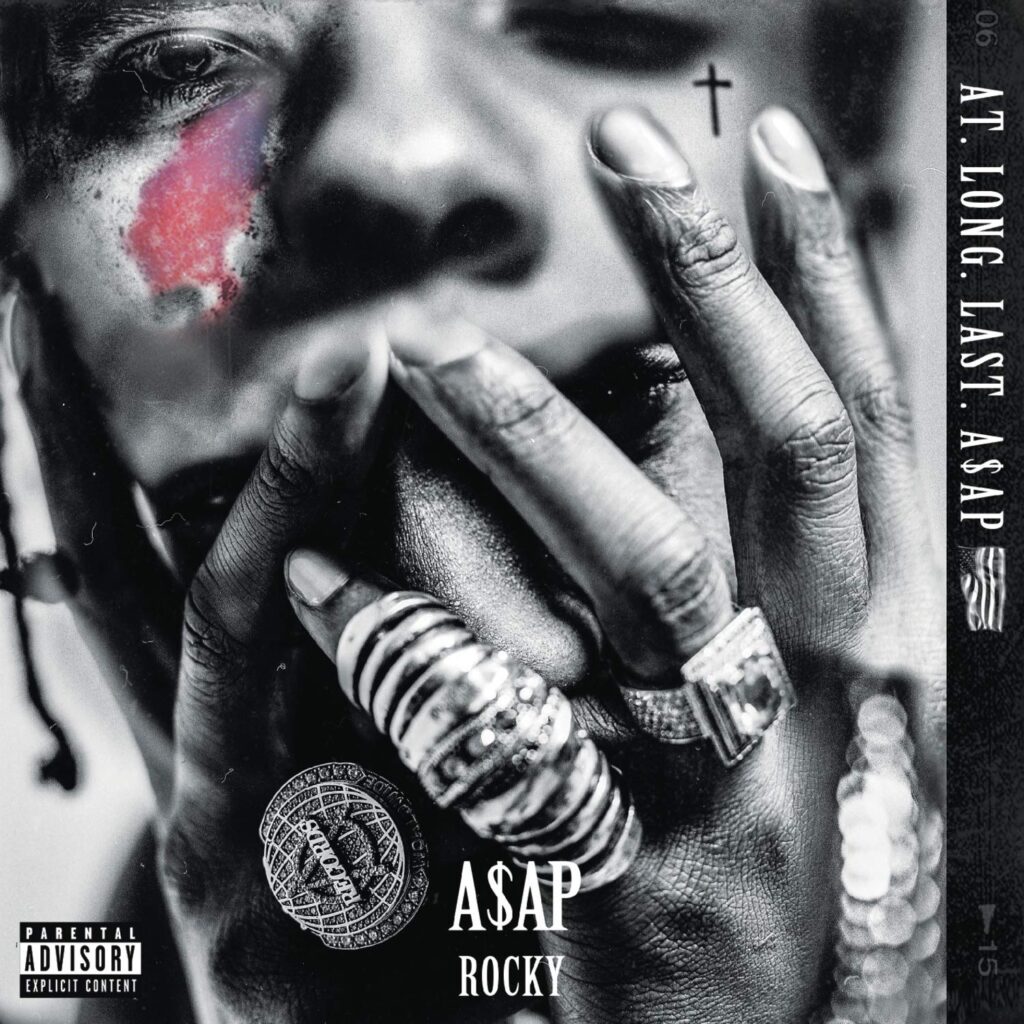

Steven Rodriguez, the Harlem hip-hop visionary known to most as A$AP Yams, was a rare case in which the function ended before someone called 9-1-1.

“Yams was like a mystery,” A$AP Rocky told the New York Times about his presence in the rap game. “He was like the Great Gatsby.”

Rodriguez was seventeen when he founded A$AP Worldwide. In the studio, he was a driven, fervent, future-focused mastermind, hellbent on crafting the Houston/Harlem hybrid sound that carried the collective through its early days.

Everywhere else, however, he was struggling to stand up straight. He was slouched unconscious on a couch. With cups of Sprite mixed with codeine cough syrup in-hand, there were times that friends caught him choking on his own tongue.

Yams came up with the pseudonym in a Mcdonald’s restaurant, seated alongside fellow crew members.

“We decided to call ourselves the Piff Crew,” he said in a 2014 Noisey documentary. “We ran with that for like two days.”

But mid-lunch, a rebranding proved necessary. “I fucked up. The new name of this shit is ASAP.”

Members laughed: The As Soon As Possible Crew???

But Rodriguez made it make sense.

“It’s been rough for all of us, but if it’s one thing I could repeat to myself in my mind, it’s Always Strive and Prosper,” he told Vice.

Things were looking up by the dawn of 2015. Yams had just executive-produced Rocky’s swanky sophomore project, the Mob had begun work on their first collective shot at emulating New York’s elusive posse-cut foundation, and two members were signed to major record deals.

But on January 18th, Rodriguez lay in bed motionless. Pools of vomit caked the mattress beside him. He was dead.

In Hello, a song mostly about narcotics and vulgar obscenities, Eminem touches on balance. “My equilibrium’s off,” he raps. “Must be the lithium.”

Equilibrium is the focus. It’s a key concept in perfecting any working relationship between artistry and drug use – a concept that, for many like Yams, has led to fatal battles with persistent temptations to go over the edge.

Alongside Steven Rodriguez, names like Jimi Hendrix, Amy Winehouse, and Jim Morrison populate a long list of fantasists who have not made it back from their alternate realities.

Stephen King is not on that list. After he had his garbage bag of drugs poured out before his face in 1986, he gave up the psychedelic world he had spent the past few years living in. Upon his return to Earth, he declared that between creatives and others: “We all look pretty much the same when we’re puking in the gutter.”

The tommyknockers agree. They watch, eyes set on a new mind to host.

The party is fun while it lasts.

If you don’t decide when it’s over, they will.