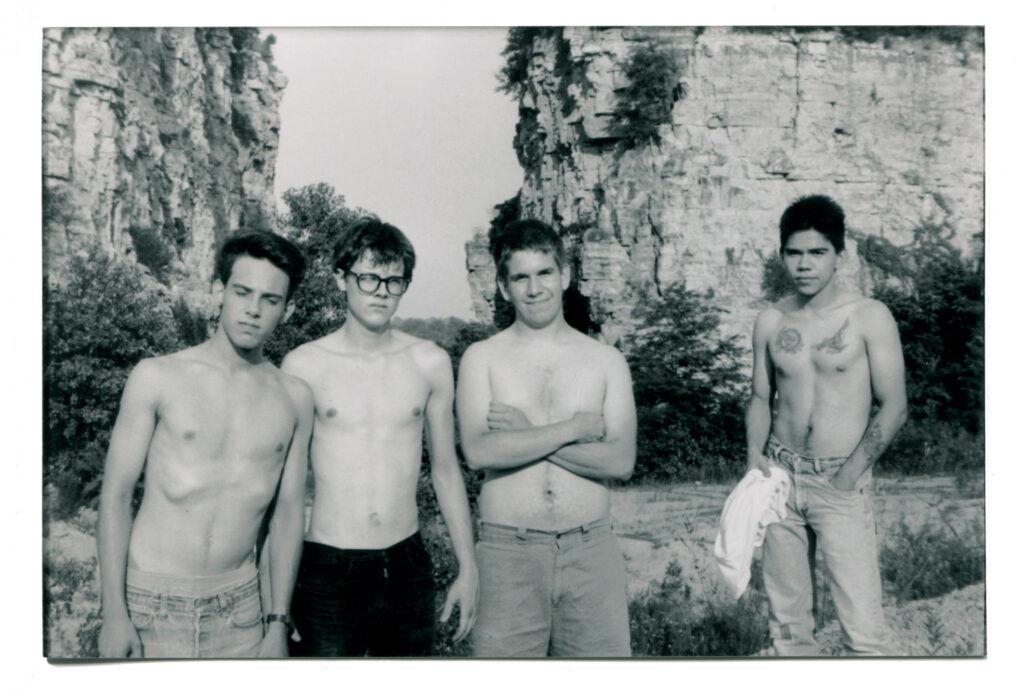

In a bustling Louisville underground of upstart 1980s high school rock outfits, Slint made music that was weird enough to survive the internet. (PHOTO: via Rolling Stone)

SAMUEL HYLAND

When I searched for the band Slint on Spotify while preparing to write this piece, the most baffling result wasn’t the band itself – which is indeed quite baffling – but the app-curated playlist they were advertised to be featured on: “Math Rock.” It’s one of several obscure subgenres to a culture that has fielded copious forks in the road. One would notice that familiarity with a select few of them has grown into a sort of rite-of-passage for disillusioned teenagers – some may have latched onto grunge when they didn’t fit in with the middle school hip-hop heads; others may have embraced the punk rock of the Stooges in their rebellion-stemmed attitude eras; they all conclusively end up with Unknown Pleasures posters in their dorm rooms come freshman year of college. But then there’s math rock. If there’s anything that rock subgenres have in common, it’s that they all hail from the same conceptual “underground” – somehow, even with decades of traceable history under its belt, math rock has managed to exist a level considerably beneath that. “Welcome to the universe of complex rhythms and mesmerizing loops,” Spotify’s official playlist description read. I was more scared than enticed.

The only reason for which I was perusing mysterious Spotify playlists at 4 AM on a school night was that I had stumbled upon Slint, an equally odd alt-rock outfit, on the internet. Before their disbanding in 1992, Slint’s final lineup consisted of guitarist-slash-vocalist Brian McMahan, guitarist David Pajo, drummer-slash vocalist Britt Walford, and bassists Todd Brashear and Ethan Buckler. Their story started in similar fashion to most: somewhere in the bustling countrypolitan infrastructure of late 1980s Louisville, Kentucky, a group of local high school-aged teens got together and started jamming. It was more a posthumous get-together of dissolved bands from the area than a straightforward initiative. Walford and McMahan had attended the Brown School, a Louisville public school predicated upon self-directed learning, and began performing together in pubescently-titled acts like “the Languid and Flaccid” and “Squirrel Bait.” (SW is a pro-squirrel publication). Pajo and Walford were in another underground Louisville group called Maurice, but after they began listening to Minutemen, their musical direction grew incompatible with the rest of the band, and they were consequently ousted. When McMahan joined forces with them not long afterward, Slint – named after McHahan’s pet fish – was the result.

“The knowledge is in your hands now – and you can’t unsee, unhear, nor undiscover what you got yourself into.”

From the onset, Slint was shrouded in mystery. There was no internet to confirm whether or not rumors were true, nor put a cap on how outlandish the hearsay was allowed to become – as soon as they went quiet for longer than usual, the group became the subject of countless urban legends that insisted that they had died in a gruesome car crash, or committed mass suicide. Big-time music magazines were not very interested in sending journalists to the trenches of Louisville’s D-I-Y high school startup scene, so conclusive interviews were out of the question. The only time one heard from Slint was when they released music – and with that as the sole premise of communication if you didn’t go to school with them, you had a lot to be worried about. Rumors of premeditated mass suicide started to not seem so far off. Profiling a mutual friend of the band for GQ in 2018, the journalist Alex Pappademas described their musical output as “the kids from Stephen King’s It, grown to late adolescence, picking up guitars to whisper of their trauma over lurching, psychically destabilized prog-punk.” The cover image of one of their most popular albums, Pappademas added, “looked like evidence—a black-and-white shot of four dudes up to their necks in quarry water, the kind of picture a true-crime documentary might linger on as a symbol of questions left unanswered.”

When the sonic element is added to the equation, it soon becomes clear that the music is exactly what may be playing before Nightline cuts to commercial too. Picture the eerie image gradually being zoomed in upon on-screen, as a semi-authoritarian, speculative female voice utters the most enticing cliffhanger of the past thirty minutes: They went to the lake often… but for three out of the four, this would very quickly turn into their last swim… Perhaps Slint is the soundscape that’s making you clutch the covers a little tighter. Their first album, 1989’s Tweez, was released quietly by Jennifer Hartman Records and produced by the outspoken hard rock staple Steve Albini. The music on it is uncomfortably gruesome and misshapen, jagged edges poking through any and all prospects of palatability. A song like “Pat,” for one, buried down at the second-to-last slot on the full-length, opens with the kinds of jangly grunge-esque guitar arpeggiations that put Nirvana on the map. You start to think it makes sense. I’ve heard this exact thing before – maybe this is where Soundgarden got it from?? This isn’t too bad after all! Grunge before grunge! That authentic underground stuff! I’m listening! But no more than a minute after you reach your conclusion (literally – the joy only lasts for exactly 30 seconds), all sound abruptly cuts out. There is an antagonistic voice coming in over a radio intercom. “Canker loaf,” it growls. “Tweezer fetish. Snatch feast.” And from that point on, you’re thrust into a seemingly endless musical purgatory, where you are in the center of a room, and all of the instruments are yelling at you. Everything is on-edge. There is tension, and no resolution. No clear verse, no clear chorus, no clear bridge or denouement: just canker loaves, tweezer fetishes and snatch feasts. It doesn’t make the anxiety any better that the creepy radio intercom is on replay all throughout.

Whereas their debut album came from (and still exists in) a void defined by a lack of publicity, Spiderland, their second and final LP, became a cult classic by the time its creators had already disappeared into thin air. “Spiderland,” the Pitchfork contributor Stuart Berman wrote of the album in a laudatory 10/10 review of its 2014 reissue, “—their second, final, and ultimately most revered album—wasn’t some painstaking, Loveless-scaled masterwork belabored over in the studio for months on end; it was a collection of six pared-down basement jams recorded over a single weekend, with many of the lyrics rush-written at the last minute.” What makes the record harrowing from its opening seconds is the sense that it wasn’t created with regard to your listening experience. There are two primitive sides to releasing a body of work: the artist and the audience. Spiderland exudes an implication that it was exclusively created for the artist and no one else. The feeling exists that you aren’t allowed to be listening to it, and for every moment that you do so, you are submersing yourself deeper and deeper into a manifesto that was forgotten about by authorities who couldn’t crack the corresponding case decades ago. The knowledge is in your hands now – and you can’t unsee, unhear, nor undiscover what you got yourself into.

We aren’t scared of the dark because black is scary; we’re scared of darkness because of the endless possibilities of what could exist within it – Slint may not have become so with strategically calculated intent, but they were the monster under the bed. We didn’t know them. They knew us.

Album-opener ‘Breadcrumb Trail’ was the first Slint song I ever listened to. It was well past midnight on my aforementioned “Math Rock” Spotify playlist wormhole, and I had just finished Young Nudy’s DR. EV4L, which had come out two days earlier. Musically speaking, the mood was set for fast-paced substance only. I needed energetic outbursts to power me through the rest of my homework, and having come across Slint on a spree of procrastination-spurred internet exploration, the decision to press play on Spiderland was mindless. It seemed to represent an obscure brand of heavy-handed don’t-tell-mom-and-dad rock music from the same class of my middle school heroes, and it looked to be something that would blast me out of my headphones. I was both right and wrong. ‘Breadcrumb Trail’ opened with the brand of lightly distorted, off-kilter string assemblages that evoke the Velvet Underground and Joy Division. It was mellow, but the perception of impending doom was incrementally tangible.

The lyrics were not sung, nor shouted, nor omitted – they were spoken, in the quivering, monotone voice of someone who has seen things they should not have seen, in full and complete sentences:

I stepped out onto the midway. I was looking for the pirate ship and saw this small, old white tent at one end. It was blue and had white lights hanging all around it.

I decided to check out the tent, it seemed I could hear music coming from inside. As I walked toward it, I passed a crowd of people at the sideshow. I couldn’t figure out why they would want to wait in line.

I pulled back the drape thing on the tent. There was a crystal ball at the table, and behind it, a girl wearing a hat. She smiled, and asked me if I wanted my fortune read. I said okay and sat down. I thought about it for a minute, and asked her if she would rather go on the roller coaster instead.

“Much like the fictional neighborhood children of Derry, Maine, one did not have to want an encounter with Slint’s music in order to have one. All it took was exposure.”

Then – as soon as the monologue came to a close – there was blood curdling shouting. There were guitars that screamed at you louder than they did in “Pat.” Too little logic for me to follow in full, but too much noise for me to keep doing my homework. It continued on this way, soon powering onward to a strange section of (kind of funky?) electric guitar screeches and drum breakdowns, with some more monotone speaking. “Far below, a soiled man,” the voice was whispering, now. “A bucket of torn tickets at his side. He watches the children run by. And cleans his teeth.” Upon looking up the song later on, I would come to realize that it was about a boy who fell in love with a fortune-teller at a carnival. When you’re hearing Slint for the first time, though, no matter how innocuous the messaging may be, everything feels like a cliffhanger: like the spooky cover art demands itself, whether intentionally or unintentionally so, the air of a true crime documentary on the verge of a very gruesome turn of events is ubiquitous and unshakable.

It’s a quality that registers as synonymous with Slint at-large. In the decades that unfurled since Spiderland’s release, so did its legacy, with the same esteemed magazines that the group didn’t make the cut for years ago publishing lengthy features and in-depth raves on seemingly every notable anniversary of the album’s release. But in the punctual few-year span that the band did see the light of day, there was virtually no information, aside from their music, to be correctly attributed to their cause. One had to piece together what they could. And it wasn’t just one person – it ballooned from a miniscule sect of Louisville, Kentucky, then expanded to Kentucky en masse, soon to proliferate limitlessly beyond these bounds as Spiderland began to pop up on myriad all-decade rankings and editorial revisitations after-the-fact. Both sonically and empirically, Slint played on the primitive fear of the unknown. We aren’t scared of the dark because black is scary; we’re scared of darkness because of the endless possibilities of what could exist within it – Slint may not have become so with strategically calculated intent, but they were the monster under the bed. We didn’t know them. They knew us. It helps to re-hash Pappademas’ likening of their position to Stephen King’s It. Slint was the demon that only revealed itself to the people it lured in, and Spiderland was the single balloon that lured them all down the gutter.

Much like the fictional neighborhood children of Derry, Maine, one did not have to want an encounter with Slint’s music in order to have one. All it took was exposure.

“When I first heard Brian McMahan whisper the pathetic words to ‘Washer’, I was embarrassed for him,” Albini said of the recording process in a 1991 Melody Maker review. “When I listened to the song again, the content eluded me and I was staggered by the sophistication and subtle beauty of the [guitar] phrasing. The third time, the story made me sad nearly to tears. Genius.”

In the aforementioned 2018 GQ profile, it is revealed that the person behind the camera for the famous Spiderland photo was Will Oldham, the multi-faced country-adjacent singer who, too, emerged from the underground of Louisville, Kentucky. “The quarry photo was taken by Oldham,” Pappademas wrote, “who couldn’t play an instrument but participated in the scene by lurking at its edges with a camera.”

Will Oldham grew up within the same mechanized infrastructure of late 80s high school bands that Slint hailed from; and, in more ways than just the photograph he took, was in close proximity to the group in general: his brother Ned played bass for Slint in early lineups, Will himself also bounced around from musical identity to musical identity, and both parties dealt with limited attention from the press when they initially sought to make their efforts profitable.

But most importantly, the sense in which both Oldham and the band found (and still do find) themselves akin lies within existence outside of the larger canon of music as a cultural gauge. And not just mere detachment – willful detachment.

Acquaintance with popular music’s ebbs and flows has grown into, over the past several decades, more and more of a rite of passage for participation in American culture. Perhaps the most dynamic representation of such a construct is the refined role of streaming services: if you listen to music via the hyper-accessible medium of technology, you are naturally thrust into the worldwide network that is the internet. If you don’t, yet, no matter if this was your intention or not, you are irreversibly off the grid. You don’t really exist. Nothing you say, hear, or do matters unless it’s on the internet, and your decision to subvert its influence serves as its own indefinite punishment.

Speaking to GQ, Will Oldham made it absolutely clear that he was against all forms of digital consumption – or, rather, “this corporation-created swamp that’s co-opted many people’s ways of finding out about and experiencing music.”

“It really is just like saying, You know what? I just buy everything at Walmart, because it’s so easy,” he opined. “People rail against Walmart, but they’re fine with the streaming services. I don’t quite understand. You’re basically saying, I don’t value the relationship I have with a record store, with a record label, with a musical artist. I don’t value any of that at all. I don’t value that connection. All I value is my experience of quick, easy consumption.”

Part of why Oldham was an enigma up to that point was that he removed his entire discography from Spotify and Apple Music in protest of technology’s omnipresence. The GQ profile was published, partly, in conjunction with the fact that he was finally re-digitizing it all after several years. When fans expressed joy at the fact that they were, at long last, able to revisit old classics, he didn’t lavish it – it was a subject of scorn. He even had the outlandish idea of releasing new singles strictly via exclusively manufactured objects, which, Pappademas wrote, was said “like he knows he’s not going to persuade Drag City (records) to release his next single as a birdhouse that costs as much as a used Hyundai instead of putting it on iTunes. His point is that he feels alienated by the way people experience music nowadays, and that it’s led him to wonder why he bothers with putting out records at all.”

In the cases of both Slint and Oldham, a lack of the internet made all the difference between run-of-the-mill public relations, and off-the-record mythology that managed to seep through the cracks of time. Yes, for both parties, the compromise of artist-to-audience relations made for a strugglesome ascent to the top – but if there is one thing attainable from reclusivity that cannot be achieved via high-level marketing, it’s cult stature… no matter how long it takes for it to manifest itself.

The prospect of being off the grid as an artist, especially in such a time as now, breeds a number of threats to legacies arguably far better off having taken the commercial route: the biggest of them all being that time can – and will – forget you. People are afraid of the dark; and by law of human nature, if you make your bed in the shadows, lying in it is somewhere in your future.

This Heat, for instance, were a British rock outfit that both emerged, and dissolved, at the height of the Cold War. Their music was meant to audiate the angst of a world seemingly on the edge of self-created extinction every day – but, for the majority of the time that they were together, the message never found itself able to reach the masses it sought, trapped in a constant courtship with the confines of mini scenes and tiny fan bases that flocked solely from one fateful John Peel session. It wouldn’t be until the 21st Century that their work – more specifically, their defiant final LP Deceit (1981) – would attain widespread reverence as a vital fragment of the 1980s’ pivotal soundscape. “This Heat were many things, but popular was never one of them,” Pitchfork contributor Dominique Leone wrote in a whopping 9.0 review of Deceit’s 2002 reissue. “It’s almost funny to see this record getting so much deserved attention recently due to its reissue, because before now, I only knew a few people who had even heard of the thing. It’s especially strange to see all the praise in light of Gareth Williams (the group’s longtime bassist and vocalist)’ death on Christmas Eve last year. He wasn’t a person who ever really wanted to be famous or even known as a musician, and yet will doubtlessly be better known henceforth than he’d ever been during This Heat’s existence.”

The prospect of being off the grid as an artist, especially in such a time as now, breeds a number of threats to legacies arguably far better off having taken the commercial route: the biggest of them all being that time can – and will – forget you. People are afraid of the dark; and by law of human nature, if you make your bed in the shadows, lying in it is somewhere in your future.

At some point, though, the light is inevitably turned on. Everything that time loses track of, whether by way of digitization, reissues, or grassroots documentaries, eventually finds its way back. And – no matter how grotesque the music itself – delving into the gutter will always be more appealing than ignoring the red balloon.

One reply on “The Band That the Internet Remembered”

youre a genius.