THE B-52s WERE NEVER MEANT TO SURVIVE.

The B-52s epitomized one of America’s most pivotal cultural renaissances. For the exact same reason, they – along with many others – were never meant to see the light of day any further.

SAMUEL HYLAND

One February morning in 1998, the then-upstart young entrepreneur Bill Gates found himself in Brussels, Belgium, to visit European Union officials for a series of meetings pertaining to Microsoft’s international presence. He emerged from a chauffeured vehicle, beaming towards tabloid camera flashes and embracing the suited associates that sauntered by his side. A man in front of him was filing through papers in a briefcase. Another person behind him was nodding graciously towards media professionals. Gates himself was turning a corner into the meeting spot, smiling and waving as he strutted his way up a shallow set of stairs.

Then someone threw a pie in his face.

It was done forcefully and with intense aggression – not the kind of face-pieing that frequents juvenile birthday cake-cutting rituals, or retirement parties that tend to tone down the antics for old age. He was visibly shaken. His arms erratically flew up in the air; he stopped dead in his tracks, and a crowd of devotees haphazardly converged around him. It looked a lot like the 1981 assassination attempt of Ronald Reagan by Soviet assailants: there was the king, dramatically in distress, and wherever there was a lack of security, there appeared an immediate abundance of suit-and-tie associates who had never felt this much adrenaline in their lives. Your wish is my command, Mr. President!

There was an audible gasp. The crowd stuck to Gates like a portable fortress, and hastily raced to usher him into the building safely. Then he was hit in the face with another pie. And – just when it appeared to be over – yet another pie exploded onto the quivering mass that you wouldn’t believe was the overarching tech-mogul of the free world.

Contrary to what it looked like in action, there was no ulterior ill-intent to the incident besides good fun. The perpetrator was found to be Noel Godin, a famed Belgian prankster who took responsibility for his actions live on television after being released from custody that night. “Godin, a fun-loving anarchist, has made a name for himself targeting the rich, famous, and pompous with cream pies,” CNET wrote in a report shortly after the ordeal concluded. “His exploits have become so renowned that a French word has been coined to describe the act of being creamed: entarter.”

But even though mal intent was absent from the case in reality, it represented, in many ways, a shifting culture towards olden structure in America that stemmed from advancements made a decade prior. Just like he does today, Bill Gates represented the preconceived model of how things were supposed to work. He was a prolific business mogul, a nerd building a technological empire upon ideas that were supposed to take America into its next frontier. Money was everywhere. Fun was not. And although he is, very arguably, the sole figure that Western culture’s newfound immediacy can be traced back to – the very opposite of that dynamic was what made him an outlier in the future he himself invented.

In the 1980s, pop musicality writ-large underwent a similar shift from the trenches of lifestyles past. Whereas contemporary music in its early stages primarily consisted of bluesy drawls and intricate, slow-winding chord progressions, the essence of recordings quickly morphed to fit a nationwide mold of commerciality: production wasted little time taking center stage over lyrical matter. People didn’t resonate with the words; they resonated with the sound. Lyrically too, even, it was not as appealing to sing about heartbreak over acoustic guitars as it was to distort the same instruments, and clamor about fun instead. Prior to any such point, the term “pop music” was simply shorthand for “popular music.” Now, it encompassed an entire genre – a sprawling self-created universe of perky synthesizers, squeaky-clean vocal leads, and sharp-edged, cookie-cutter instrumentation.

“It was a quirky nature that quickly carried over to sound – their voices were at times just as squeaky as the cartoon characters they looked like; and at the same time, the instruments sounded like the utopian candyland that the cartoon in question was set in.”

In a 2012 New York Times interview following his nomination for several awards at that year’s Grammys, the producer Paul Epworth told one journalist that “pop music has greater power to change people and to affect people because it’s a universal language.” Epworth had seen such power harnessed firsthand: on top of producing for acts like Bruno Mars and Paul McCartney, three projects he himself helped bring to fruition – by Adele, Cee-Lo Green, and Foster the People respectively – were favorites to win big. “You don’t have to understand music to understand the power of a pop song,” he added.

Primitive approaches, in the 1980s, gave way to a right now-ism that deemed overthinking too time-consuming to be viable. America needed new music, and America needed new music right now. It was a movement that, whether influenced by it or not, directly reflected the country’s position in a grueling Cold War. With a sociopolitical climate that saw tensions escalate to highs like the aforementioned Reagan assassination attempt, everyone existed on-edge, because the world was perpetually on suicide watch. School students learned to take shelter from nuclear bombs on their lunch breaks. “TEOTWAWKI” grew a newer, uglier head called Mutually Assured Destruction. Culture was always America’s dopamine, and now that there was a shortage of its effect, dependency proliferated to extents that only immediacy could fix. America was addicted.

Although they are often obscured in discussions surrounding the period, The B-52’s musically embodied an essence that their respective heyday made inescapable. Coming to form in the late 1970s, the group’s original lineup consisted of vocalist-slash-drummer Fred Schneider, vocalist-slash-keyboardist Kate Pierson, percussionist Cindy Wilson, guitarist Ricky Wilson, and multi-instrumentalist Keith Strickland. They had an outlandish, in-your-face affect that registered often as a de facto trademark, the girls donning comically enormous hairdos reminiscent of squeaky-voiced cartoon wives, and the boys sometimes sporting futuristic sunglasses from sci-fi film sets and war-stemming television programs. It was a quirky nature that quickly carried over to sound – their voices were at times just as squeaky as the cartoon characters they looked like; and at the same time, the instruments sounded like the utopian candyland that the cartoon in question was set in.

In one Rolling Stone feature from late 1980, for instance, the journalist James Henke detailed demographic makeups of a December tour stop in California: “The Crowd crammed to capacity inside the Greek Theater, a 4,700-seat amphitheater nestled in the hills above Hollywood, looks like it’d be more at home at some bizarre, early-Sixties fashion show than at a rock & roll concert,” he started. “Take, for example, the three girls sitting a couple of rows in front of me. They couldn’t be more than about fourteen years old; they’re so young, in fact, that one of their fathers is along as a chaperone. Each girl is wearing a brightly colored miniskirt — one’s fire-engine red, another’s fluorescent orange, the other’s indigo blue — and their faces are piled with scads of makeup to match. Then there are their hairdos: One has little pigtails sticking straight out each side of her head like TV antennas, another has a braided ponytail hanging down to the middle of her back, and the other has her hair puffed up bouffant style.”

“Time wasn’t an issue when there weren’t choices – but now that there were, time was the only thing that mattered. And just like money, it was running out.”

Yet – even as far-out as they appeared to be externally – there was an ethos to their output that one couldn’t possibly disregard. The same year that they were performing in front of raucous crowds of giddy Hollywood middle-schoolers, John Lennon was declaring that they were his favorite band. (Lennon would go on to say that their 1979 single “Rock Lobster” directly inspired him to record his comeback album Double Fantasy with Yoko Ono. “I said to meself, ‘It’s time to get out the old axe and wake the wife up!’ he told Rolling Stone). A similar line of legitimacy is easily drawn to their positioning in the general soundscape of the 1980s. The B-52s’ music was immediate. It packed vibrant bursts of energy into tight verse-bridge-chorus packages, manufacturing specific emotions in ways that saw them stripped-down enough to be mass-produced, but digestible enough to be tangibly felt. Not much time passed before they would reach cult stature. Early singles landed them coveted gigs at nightlife staples like New York’s CBGB. Major music magazines flocked to cover the bustling scene they were rapidly beginning to cultivate. They weren’t the most popular thing to come out of their decade, but they represented it to an extent that even its champions often failed to replicate in-full.

“Their blend of rock ‘n’ roll and dance-pop became a signature,” Ethan Sapienza wrote for the Interview Magazine in a 2016 re-publication, “and they steadily climbed the charts before reaching their pop apex with the classic hit ‘Love Shack’ in 1989.” The interview, originally published in 1979, was digitized in support of an upcoming tour the group was set to kick off soon afterward. They were two decades past their zenith (and one member down – Wilson died of AIDS-related illnesses in 1984). Still, yet – much like the culture they emerged within – The B-52s had outlived quick beginnings en route to a shot at long-term survival. “While they dropped the apostrophe from their name in 2008, and they may no longer be ‘headin’ down the Atlanta highway, lookin’ for the love getaway,’ they’re still going strong,” Sapienza concluded.

The first time I heard the B-52s’ music, I was sitting in a Nashville Hard Rock Cafe, picking away at pseudo-spicy fried shrimp while making involuntary eye contact with the person who happened to be sitting closest to a nearby mini MTV screen. R.E.M’s 1994 single “Star 69” was blaring over boisterous restaurant speakers. I enjoyed it, because it was directly reminiscent of the clean-cut new wave punk that a sixth grade me listened to wide-eyed underneath borrowed headphones; it was the kind of song that populated soundtracks of the dust-covered Xbox 360 skateboarding games in your uncle’s attic, enjoyed best after years of hopeless Googling. When the guitars faded out, and the B-52s’ “Legal Tender” made its way into the soundsystem, there was a difference that you could feel. This time, there weren’t angry drums, abrasive call-and-response dynamics, nor arena-friendly refrains – rather, it sounded like Kidz Bop: the voices were too enthusiastic to possibly be serious. The percussion sounded like it was coming from a Little Tikes drum machine. And, in a more literal sense, I hadn’t heard synthesizers that sounded like this since I received Kidz Bop: 80s Gold as part of a McDonald’s Happy Meal at eight years old.

But most strikingly, in a wholesome, near-nostalgic way, it was something I had to enjoy. Legal Tender’s appeal exists in its simplicity. Taking a liking to it requires one to be mindless. I myself was (and still am) exclusively conditioned to the idea of music as a complicated entity that requires constant analysis – just that week, I had fallen down a “math rock” rabbit hole and struggled to find some kind of meaning – but, at the end of the day, I couldn’t just walk out of the restaurant. I had to hear what was playing. And by the time it finished, I was humming along to any and all last few bits of sound that were graspable before the track fizzled into its successor.

The bubble-gum candy-pop appeal of “Legal Tender” takes a dark turn when considered alongside the track’s actual meaning: though it sounds like the scene in a Pixar film where the two love-stricken protagonists finally kiss, it’s really about a homegrown money laundering operation. “Living simple and trying to get by,” Pierson sings, as punchy electric guitars lurch beneath candy keyboards amidst her croon. “But honey, prices have shot through the sky! So I fixed up the basement with what I was a-workin’ with / Stocked it full of jelly jars and heavy equipment / We’re in the basement / 10-20-30 million dollars, ready to be spent!” It’s a tiny fleck that manages to cover an overarching dynamic of the American 1980s: underneath glitzy highs of a culture that was now seeming to find its footing going forward, there existed sociopolitical hellscapes that burned beyond the confines of the camera frame. The duality very much does still exist. When I spoke to the band Crumb for Rolling Stone over Zoom on one April afternoon, they were quick to point it out about Los Angeles, where they had spent the past few months recording their second studio album. “As a place, it looks one way, but it may actually be another way,” singer-guitarist Lila Ramani said. “It looks so serene and peaceful, but to me, there’s an underlying darkness and hellscape energy to it.”

America, much like the pivotal decade that the 1980s existed as, is a complex array of the thrillingly beautiful and the horrifyingly ugly. Music only serves to reflect whichever side of it the artist exists on – and even then, the possibility will always exist that we’re consuming it too fast to see the right picture.

In “I Am Trying To Break Your Heart,” a mini-documentary about Wilco’s 2002 breakthrough LP Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, the then-Rolling Stone senior editor David Fricke attributed positive reception of the album to changing ideas of immediacy in U.S creed. “We are now in a culture – not just a business, but a culture – where we expect everything to happen (snaps) like that,” he started. “You have people outside standing around, talking on cell phones – the gist of the conversation is ‘I’ll be there in five minutes.’ Who gives a fuck? Just be there in five minutes. Don’t talk about it.”

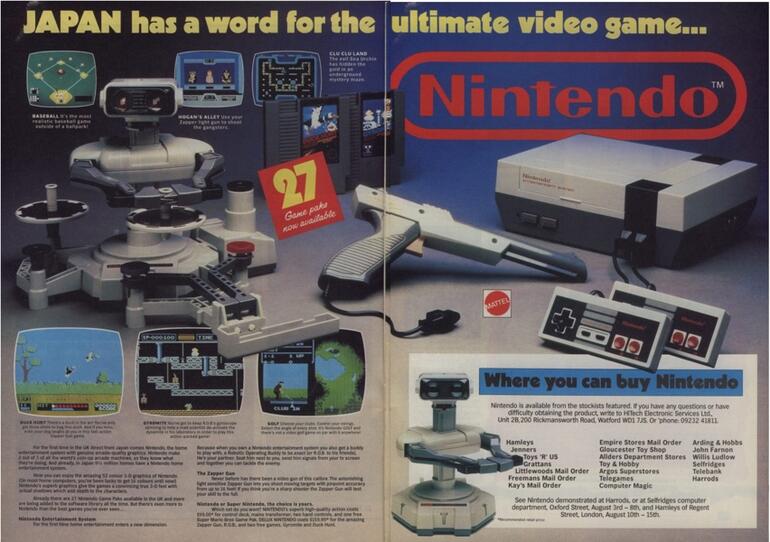

In decades prior to the shift Fricke alludes to, it was commonplace for the process to be just as much, if not more, appreciated as the result. Parents were delighted in teaching their kids how to ride bikes. To sit down and read a newspaper from front to back was more of a daily ritual than it was a feat of human patience. The house phone was, aside from being a luxury, the site of hours-long conversations between parties for whom the other person was the sole living earphone to the outside world. With the 1980s, yet, there was suddenly the need to contend with endpoints that now culturally towered over whatever means they could have taken to be reached. The microwave could cook in thirty seconds what the oven cooked in five minutes. The Nintendo Entertainment System could provide in ten minutes what a trip to the park provided in several hours. The internet could access in nanoseconds what a walk to the local library sometimes even failed to access in a number of years. When time became a factor, it didn’t make sense anymore to choose the primitive option. Time wasn’t an issue when there weren’t choices – but now that there were, time was the only thing that mattered. And just like money, it was running out.

Even the B-52s – the very band that, decades ago, spoke for a shifting landscape that saw itself within candy-flavored pop music – have struggled to find their footing amidst the modern record business’ ebbs and flows.

Shortage of time was a harsh reality for people who thrived on past versions of their livelihoods. The Ramones, for instance, were a legendary New York City punk rock outfit credited for single-handedly establishing the genre’s presence in the United States. Although the credit is justly an even split among all four original lineup members, Johnny Ramone, the group’s stone-faced guitarist, was perhaps the driving force behind their groundbreaking sound. He was known (and feared) for his strict, military-esque, buzzsaw power chords that blared through amplifiers at maximum volume – and it was an abrasiveness that carried over into his attitude as well: it was him that forced the group to strictly face their audiences (they very literally weren’t allowed to turn around) over thousands of live performances; it was him who was known to violently assault bandmates when they broke his strict code of conduct; it was him who stole his lead singer’s girlfriend and married her while somehow keeping the band intact through the entire ordeal.

When 1980 dawned, yet, and a completely new musical soundscape threatened to edge the group’s tough brand out of the picture, they released End of the Century. Even the album’s cover itself – an awkward faux-family portrait in front of a solid red background – represented a far cry from the culture they built a reputation upon, reaching up towards elusive modernism while still confined to the shackles of an already-defined crux. The album was gloomy at points. Faint piano keys were audible in singalong-friendly choruses. Longtime fans were turned away. “Now, assisted by (Phil) Spector’s wall of sound arrangements and hours of vocal coaching, Joey was singing his heart out—hitting high notes and emoting broadly,” Pitchfork’s Evan Minsker wrote of “Baby I Love You” in a review. “No other Ramones appear on the track, which means there’s no Johnny Ramone guitar crunch or nearly-flat Dee Dee Ramone harmonies to offset Joey. It’s all billowing, pillowy softness: wedding music.”

It isn’t a construct that is entirely exclusive to the 1980s either. Even the B-52s – the very band that, decades ago, spoke for a shifting landscape that saw itself mirrored in candy-flavored pop music – have struggled to find their footing amidst the modern record business’ ebbs and flows. Out of a sprawling discography that spans all the way to 2018, they have managed to land eight songs in the Billboard Hot 100. The last single of theirs to place on the charts, to-date, peaked at number 33. It was released in 1994.

Asked why he specifically chose Bill Gates to be the victim of a nationally televised face-pieing operation, Godin later told First Monday that “in a way he is the master of the world, and then because he’s offering his intelligence, his sharpened imagination and his power to the governments and to the world as it is today – that is to say gloomy, unjust and nauseating. He could have been a utopist, but he prefers being the lackey of the establishment. His power is effective and bigger than that of the leaders of the governments, who are only many-colored servants.”

In a way, time is a lot like Godin: it notices when we try to overstep the boundaries of its relationship with us. To attempt to ignore the passage of time is to put oneself at odds with it. You have to move with time, whether you like it or not, because the moment you step off of the conveyor belt is the moment that you are forgotten.

You can’t sit the race out, and you can’t walk to the finish line. With a culture that thrives upon immediacy, there are two options: beat the clock, or it pies you in the face.