TAKA’S LAB

Taka has done the research. Now, he’s ready to share his findings with the world.

🛰️ 🛰️ 🛰️

SAMUEL HYLAND

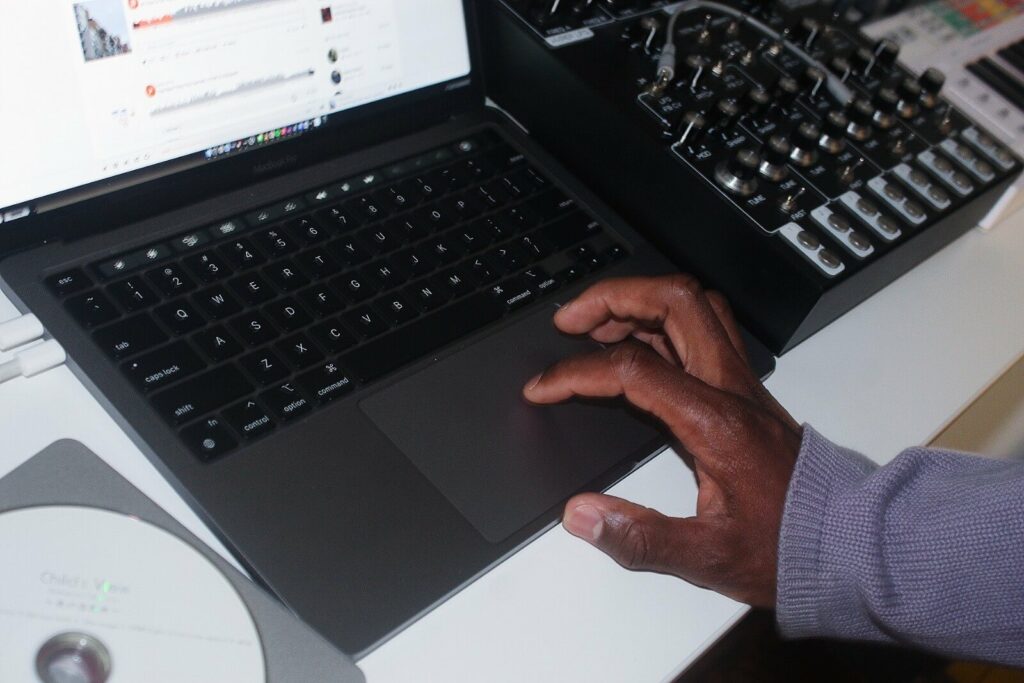

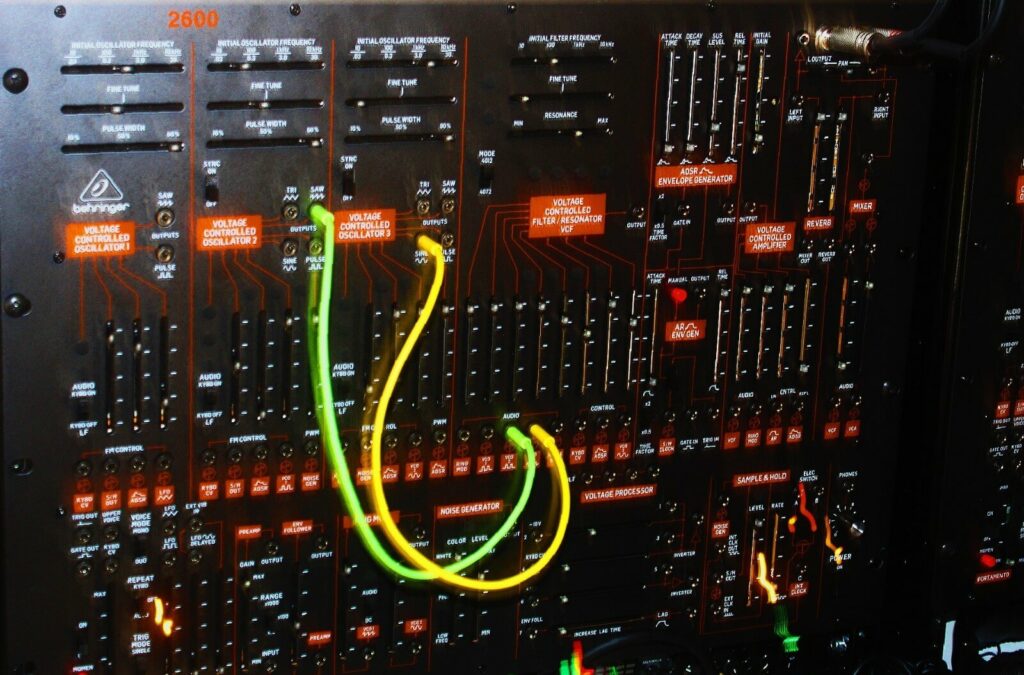

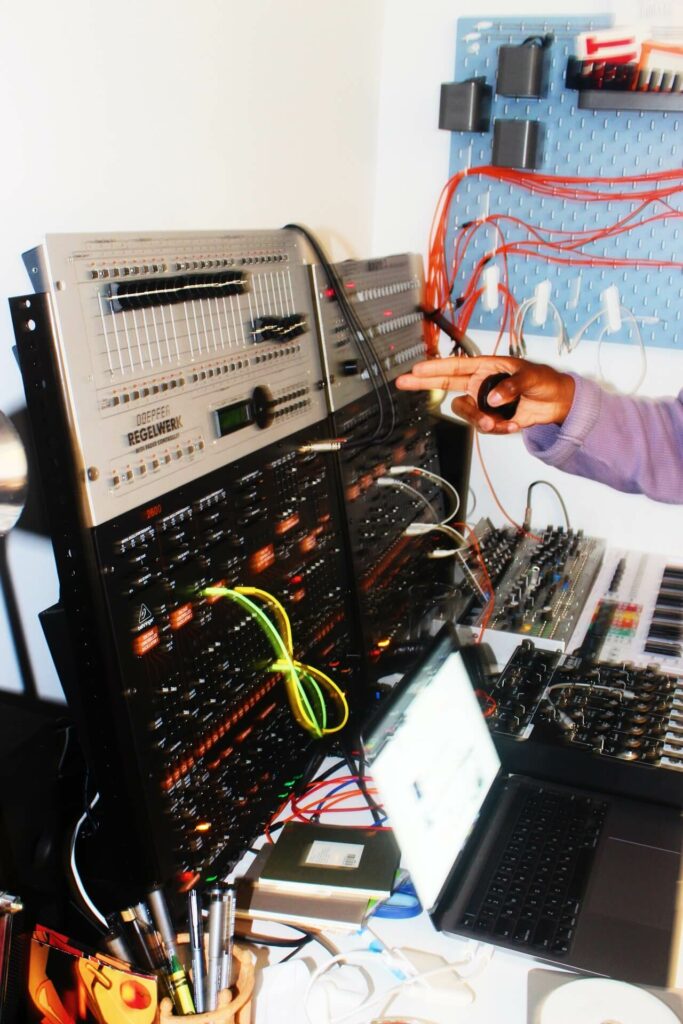

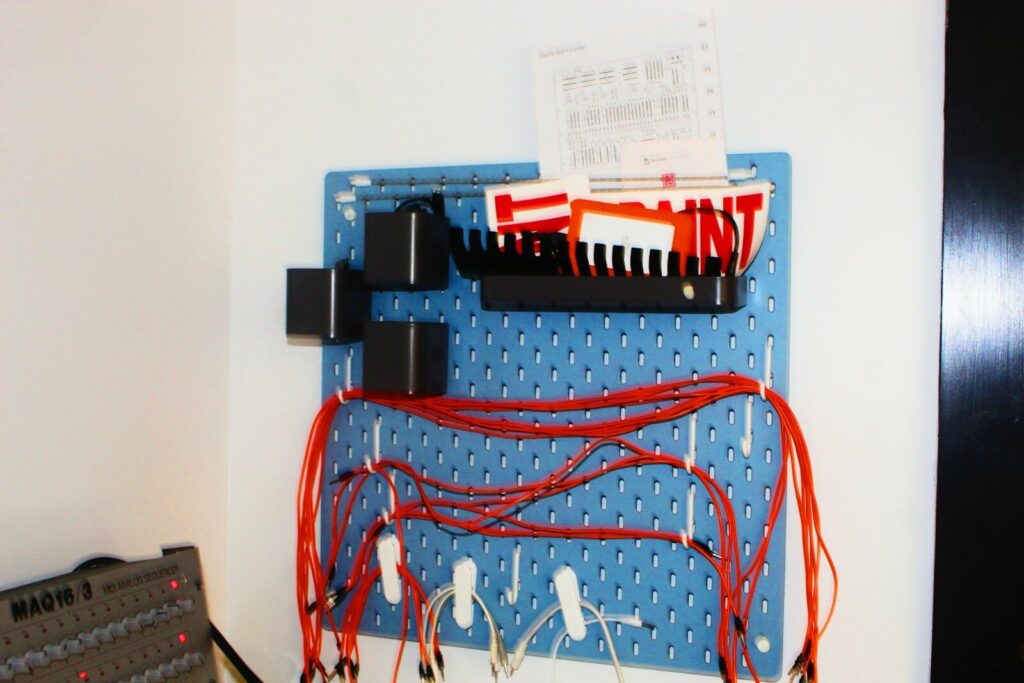

The NBA Finals are set to begin tonight, but Taka won’t be watching. It’s a little past noon in the Brooklyn apartment he shares with his wife, and ambient music is blasting from a mammoth soundsystem he’s got stationed atop an otherwise-modest desk setup. The noises, some swelling with ultra-reverbed beginner strums played on a borrowed guitar, others peppered with jagged Yeezus-esque CD scratches, and most marked by a consistent wistful sensibility, have at least two things in common: (1) they’re set to go on a project he’s releasing in the coming months, and (2) they’re far more important to their maker right now than the Boston Celtics or the Golden State Warriors. “Sometimes I’m able to dial into my own music as the listener,” he tells me, meditatively criss-cross applesauced on a wooden bench, as that seemingly-sentient maze of speakers, wires and knobs drones away on the table in front of him. Tiny red and yellow lights are blinking sporadically from machine to machine, and the more he goes on, the more he comes off as a mad scientist, the soundsystem his Frankenstein. “If people are able to resonate with that, then they feel what I feel… And everything is great,” he continues. “That’s all I want. People hear music and they’re like Oh, this fire. No — It’s water. Like bro. I wasn’t making this like This is fire. It’s a sad song. Take the time and listen to it.”

“I have to release music because it’s my science. And as a scientist, you’ve got to do your research. My music is my research.”

If Taka were to put packaging on his forthcoming EP detailing strict listening instructions, he tells me that, although we’re all entitled to our preferred modes of intake, the rule would be to listen through the entire thing, in silence, underneath a pair of headphones and with your eyes shut. (If it makes you feel any better, it’s not a ritualism he’s exempt from — with one previous track, he says that in order to decide whether it was finished, he went to sleep with it blasting on a speaker, only electing to call it a wrap when he woke up and found that he still enjoyed it.) But it’s not so much him being offended by misconstruements of his music, as it is him recognizing the underlying lack of consumption effort quick compliments like “this is fire” often tend to stand in for. When he sends a project he’s working on to his friends, the few that do respond usually just tell him that it’s good. Which, as much as it may overjoy someone else, slightly irks him. “What about it is fire?” he says. “Just sit down with it. Be a little bit more patient. You don’t have to have an immediate thought about it, or an immediate response.” The process-oriented listening gospel wastes little time ringing true, because soon, through the speaker, Kanye West’s stuffy voice is crooning about models with bleached assholes, and Taka is running me through how his criticisms of The Life of Pablo have grown increasingly nuanced in the years since its release. There’s also Aphex Twin, whose landmark LP Selected Ambient Works 85-92 he wordlessly tosses into a garbage can in one video posted to his Instagram page: “Just because I don’t get it doesn’t mean it’s bad music,” he says. “It just means I don’t get it.”

Last night, Taka attended an experimental show at IRL, a Brooklyn art gallery where he and MIKE were previously scheduled to play a DJ set alongside Vegyn. Throughout one of several jarring performances featured in the event, there was a drummer who struck his cymbals in rapid succession, as if to lead up to some sort of grand finale, then abruptly stopped every time a climax was somewhat foreseeable. Taka found it comical. “My friend was like Why are you laughing? I was like That… is… hilarious,” he says. He visited him after the show with the sole purpose of telling him how funny he found it. “What is that information going to do for him? Maybe something. Maybe nothing. But he has it. It’s good for people to know that you liked something… but how? And why?”

The show wouldn’t be the only thing Taka partook in yesterday evening. When I meet him in the lobby of his building, the first thing he tells me upon whistling his way out of the elevator is that he’s considerably hungover. He’s sporting a cozy woolen button-down top and striped pajama pants. When we get to his room, the first order of business is getting him something quick to eat. In casual talk, he’s surprisingly quick to demystify the fabled “Taka” moniker — “Oh my name’s just William,” he says with a quasi-My name is Jeff curtness, standing by the doorway while poring over what he has in the kitchen. Asked about it later, he tells me that the pen name is moreso a vision of what he aspires to be. He goes by Taka now, but at first, he was making music through a project he called “Takashi Yama.” “I’m not Japanese, I don’t know Japanese, but I did a lot of research — Google fucks you up — about what the name meant, being noble, the concept of nobility, who I wanted to see myself as,” he tells me. “But translated into a name. It’s like a person who’s noble, of high esteem, high regard. And then there’s ‘mountain.’ Takashi Yama. This person and this mountain being synonymous to each other.”

“But you have to have gratitude in the process of going up — because when you get there, it’s always going to feel good, but when you get back down, you have to understand.”

Taka is at a place in his career where he’s far more appreciative of the hike up the mountain than the fleeting moment at the peak. “Mike has always told me about the process,” he recounts. “I remember, like, five years ago, we were having a conversation and he explained it using valleys. There’s always going to be a valley. There’s always going to be some type of curvature. It’s gonna go up, it’s gonna go down, it’s gonna go up. But you have to have gratitude in the process of going up — because when you get there, it’s always going to feel good, but when you get back down, you have to understand.”

As of the writing of this piece, the primary upward climb on Taka’s agenda is his new project. The music itself is finished (unless he impulsively decides to rework several tracks — an urge he’s constantly fighting against); all that’s left to do is record a video, which may be slightly tricky given that he flies out to begin a European tour with MIKE and Sideshow tomorrow evening. Most of his creative process looks a lot like scientific research, a hefty CD collection serving as his database, and about three-hundred audio files in his laptop serving as digital prototypes. A record that’s been in heavy rotation in the Taka headquarters-slash-laboratory lately, for instance, is Björk’s 2001 offering Vespertine, an erratically-affecting LP that features geometric soundscapes, stream-of-consciousness instrumentalism, and the faded resonance of improvised jazz music. Taka says it’s one of few things that can make him cry. Before he starts dissecting one of its tracks for me on the speaker, there’s a moment where he tells me that it’s his favorite album of all time right now. He doesn’t have the words to tell me just how much he’s been listening to it lately. He calls out to his wife in the other room: “How much have I been listening to this album over the past couple of days?”

“…A lot,” a knowing voice announces behind a door.

It was only recently, after years of extensively sampling the Björk album, along with similar ones, to make his own music, that Taka organically discovered two producers integral to the sound it hooked him on. One, an obscure German electronic music faction called Oval, happens to take up a considerable amount of real-estate on his CD shelf. (“None of this shit can be found on the internet,” he says, casually handing me a stack of their Japan-sourced tapes to inspect.) The other, a Danish electronic musician named Opiate, he recently DMed on Instagram to express respect and gratitude. After Opiate followed him back, he began scouring what little information existed of him online… only to find a Björk interview in which she lauded him for his help on Vespertine. “It’s full circle,” he says. “It’s crazy that these people who are pushing me now, in a way, helped me years ago without me knowing.” Taka’s scientific approach to music hinges on a similar quality, where, whether the conclusion is a song, an album, or just a full-circle moment, the fun lies more in connecting the dots and seeing what happens, than casting his own creations as their own end-all be-alls. The work is manufactured to be more of an open-ended dialogue than a PSA.

“I can do this shit… why am I doing homework?”

In crafting the new face of it represented on his forthcoming project, he’s been obsessively experimenting with a CD-scratch technique popularized by Oval. Which is, he says, exactly what makes it a project in the first place — an experiment is being conducted, and the result is, by definition, supposed to be different than whatever the last one looked like. “People are like I’m dropping a project,” he says, “And I’m like But it’s the same as what you did last time… how is this a project? I want to release stuff knowing that every time I release something, it’s a new experiment.”

He continues: “I have to release music because it’s my science. And as a scientist, you’ve got to do your research. My music is my research.”

🧬 🧬 🧬

Something that has plagued Taka for his entire life is the mentality that, because people already know him to be capable of certain things, he doesn’t have to do them. It was this quality, on top of a tumultuous living situation, that wound up inhibiting much of the potential he had in education. In his first year of high school, he was so stellar in the classroom that his math teacher hand-picked him to be recruited by Harvard and Columbia. His principal pulled him aside at one point and told him that he was one of the smartest, if not the smartest student in the institution. “That was the thing. I was smart, but my home life was ass,” he tells me. “My school life was just a reflection of all the things I was experiencing at home. I can’t be focused if there’s so much going on outside of school. So I just wasn’t inspired by school; everything was easy and I was disinterested.”

But he was unusually intelligent, and his teachers took notice. He got nineties on all of his regents exams, and participated in his classes to the point where he would just grow bored of it after a while and stop. His issue, one repeated to him by concerned teachers, faculty members, and principals alike, was that no matter what, he couldn’t seem to apply himself. “My high school career did not reflect that type of trajectory,” he said of the Ivy League recruitments. “So I ended up failing everything, except tests. ‘Cause I’m like I can do this shit… Why am I doing homework?” There was one instance where, as he was walking down the hallway, he peered into a classroom and saw all of his teachers conferencing at desks. After he realized that the conference was literally about him, they invited him in: “they were like You need to Fix. Your. Shit. Those aren’t their words, but they were just like You’re not about to waste what you got. You’re not about to waste this shit. We’re here because you need to fix yourself in all of our classes.” In another instance, the school’s dean, who had taken it upon himself to serve as his mentor, summoned him to his office, then broke down in tears. “He was like I’ve been trying my best to fight for you,” he tells me. “But you have been making it very hard.”

“If I get on stage and I don’t do what I feel like I’m meant to do — I don’t want to have fun after that, what the hell?”

By the time Taka dropped out of high school, the energy he wasn’t using for his education was, instead, being studiously put towards a promising creative evolution. Taka’s introduction to music came through the trappings of an unstable childhood, one spent between foster homes across New York state, and in large part soundtracked by his older brother’s rap CDs. The first time he envisioned himself as a producer rather than a consumer, he was visiting family in South Carolina, and his brother boasted to him that a friend of his had made the “I Get Money” beat for 50 Cent. His brother followed up by showing him a beat another friend of his had made, this one a sample of the “Reading Rainbow” theme song, which Taka took interest in. When he asked his brother how he could start making beats himself, he set him up with FruityLoops 7. He acclimated himself with the program at his dad’s place, churning out beats he admits were terrible, until eventually, he grew bored and stopped. But by 2010, long after FruityLoops had rebranded as FL Studio, he decided to get back into it — and this time around, he had noticeable talent.

The first time Taka felt that he was doing something right musically, his mom caught him using her laptop to make instrumentals. Up to then, he had been staying up through the wee hours of the morning in the room they shared, crafting beats nightly on the computer without her knowledge or permission. (Today, he admits that the routine was probably a big factor in him failing school). “She asked me, What are you doing on that computer all the time,” he says. “I said I’m making beats. She told me to let her hear something, so I played it, and the moment I played it she just gave me the computer.”

In the time since his mom gave him her computer, Taka’s audience has grown quite a bit beyond just his teachers and his immediate family. But for the most part, it still registers as a surprise when he’s reminded that they’re there. Most people that follow him on social media, he says, probably do so because of someone else he’s connected with — albeit just as much as this may ring true, there does exist, too, a distinct, less-visible crowd that just wants to hear him for him. Yesterday, for instance, Taka visited a bar where someone he knew was DJing. Another person he knew also happened to be present, and, upon seeing him, immediately asked about the new project. “They’re like, This project. When are you putting this out. We’re waiting for that,” he tells me. “And I’m like I didn’t know that… I’m waiting for it, too. I feel like maybe I’m building an audience now, or the audience I thought I didn’t have I always had — but there are people who are looking for me to release music… I have an audience, I guess.”

The kind of audience Taka faces most often is the one he’s set to fly out to Europe for tomorrow night — on tour, he’s a consistent presence stationed at a DJ setup behind MIKE, CDs sprawled over a maze of wires and knobs not unlike the apparatus towering over his desk at home. His role in ensuring that performances go well is one he takes very seriously. “If I get on stage and I don’t do what I feel like I’m meant to do — I don’t want to have fun after that, what the hell?” he says, telling me about what the work-slash-leisure interplay tends to look like on tour circuits. “I’m going to sleep!” When he does mess up, although no one usually notices, it irks him, the same way it would irk him if he sent you his EP and you replied with a “fire” emoji in 15 seconds. One moment he winces at today came in San Francisco, on the “Small World Big Love” tour: he was taking footage with his wife’s camcorder during a performance of “Leaders of Tomorrow,” until he realized that, for a good few seconds, he had forgotten to turn MIKE’s microphone back on. Of course, most of these slip-ups are still either minor enough, or maneuvered out of so smoothly that it’s difficult to notice them live. (“I’ll be like Mike, you peeped that? And he’ll be like Nah.”) But the foundation of the surrounding strictness lies in far more than just being a perfectionist.

“I’m only there to make sure he’s able to express the power that he has.”

The first tour Taka ever went on was in support of May God Bless Your Hustle, and he was packed into a worn sedan with MIKE, King Carter, and Slauson Malone. MIKE’s mother had just passed away. “I’m here with my friend. He’s just gone through an immense loss- but he still has enough power within himself to get on stage, to do what he loves, to talk to people, and to express himself, at 100%, every night,” he says. “For me to even be able to be there and support him through that was important. And I feel like that is the reason why I take DJing for Mike, as a friend, so seriously. I’m only there to make sure he’s able to express the power that he has.”

A word Taka fixates on to describe the air of touring with his friends is “sacred.” It’s a fitting through-line to the effort he puts into his own work, the careful intake of inspiration, and the collective experience of sharing it with thousands of other people alongside longtime partners — as much as his grandiose setup may be a laboratory, it may as well be a sanctuary, too. Whatever it is, lab, holy place, or soundsystem, he’s sitting at it when I ask him what’s “up next”. Some among a laundry list of tasks to complete, spanning across both short-term and long-term scales, are paying Abe of AINT WET for some merch he’s getting made, preparing himself for the European tour, and, of course, putting out the new body of work (or, rather, body of water) poised to culminate his current experiment.

The NBA Finals are set to begin tonight, but Taka won’t be watching.

One reply on “Taka’s Laboratory”

Taka on the cusp of greatness, and SW the goat for this one.