Bryndon Cook Is Seeing Blue.

On his second full-length LP, Bryndon Cook unravels a lavish, ongoing, conversation with infinity that forces you to find forever on the inside.

SAMUEL HYLAND

Bryndon Cook has a broken collarbone. “It hurts to laugh, it hurts to sneeze, it hurts to cough . . . I fought off sneezes for two weeks. I had my first sneeze yesterday,” he tells me, after I ask if he’s found a way to continue playing music. “I can’t even put on a t-shirt. I think from that standpoint, I was like it’s just not gonna happen.”

It’s impossible, though, to detect any inkling of such agony through the computer screen as he answers my questions. Cook sits cheerfully, surrounded by keyboards, synthesizers, and drum machines, eyes constantly moving about in intrigue for wherever our conversation will meander next. The first time he asks me a question (“Have you ever had an injury like this before?”) I am taken off guard – yet, by the end of our interview, we find ourselves laughing about how I played overdriven power chords on electric guitar during Amazing Grace.

One can say that Starchild & the New Romantic sounds like a hyper-realistic examination of self: he drags you face-to-face with the ugliest crevices of your being; but by the time the music fades out, you just so happen to admire the very reflection you once obsessively avoided. On All My Lovers, the first track off of his debut effort, he laments to a romantic interest left unidentified: “Let me hold you tight / if only two hearts could make it right / But you’re gone so far away.” An impossible-to-ignore tension is maintained, from the way he drags out the ends of his bars, to the way his background music seems to occur in waves that encroach a tiny bit more upon the sand with each crest. But it is the universal nature of Cook’s lyricism that forces listeners to question: who would I be speaking to if this were me?

Get Back, from his 2019 release VHS 1138, is equally introspective, predicated upon a first-person account of love that cannot be re-ignited. Just as he reaches the climax of this eternal chase – the chorus – the bass guitar is a thumping madman, picking you up from your seat, dragging you to the dance floor. But still- who is this about? The only feasible answer is yourself. Without meaning to, you have been placed in front of an interminable mirror: now, you have nothing to look at but everything you have chosen to put aside before this moment.

With his latest album Forever, Cook seeks to emphasize the infinite facets of where he finds passion.

“There’s part of me in my heart that’s like when did soul become a bad word? When did funk become a bad word?” He gazes upwards as he asks these questions, genuinely confused as to when his influences were delegitimized. “It’s all black music, and it can be live and direct. It also has to do with what the title is, because that’s an indefinite thing in my mind – it makes me quite emotional.”

When Starchild asks me what my favorite song off of the new record is (Silent Disco), we get into a chat about Parliament-Funkadelic. It is then that I realize how deep his conviction for African-American art goes: it’s not necessarily as much of a favorite genre to play as it is a lineage he is responsible for carrying on. And no one asked him to do so – he took it upon himself. A Southern upbringing saw the journeys of both black music and the black struggle grow deeply intertwined in his conscience at youth; “From a young age, I knew a lot about my history,” he tells me. “And not necessarily my family’s history — but Black, African-American, post-slavery, coming from sharecroppers, like- my dad is born behind a cottonfield. You know what I mean? It’s real.” Born to parents with backgrounds in education, Cook comes off in our interview as self-educated on every last thing he’s passionate about. He effortlessly walks me through the complete history of American funk music as if he has flash cards under the camera; he speaks irritatedly of Blonde copycats failing to create for themselves; he happily recalls learning every single song on Rick James records as a guitar-slinging teenager in love with music.

“You have to find your inner peace at the same time that you’re recognizing traumas, tragedies, all kinds of stuff.”

Forever sounds like the marriage of these ingredients, the moment in the book where the title finally makes sense. Like a mad scientist, he takes every element that has gone into his past – the pain, the passion, the influence – and pours it all into a timeless ode to all things just that: Timeless. Infinite. Everlasting.

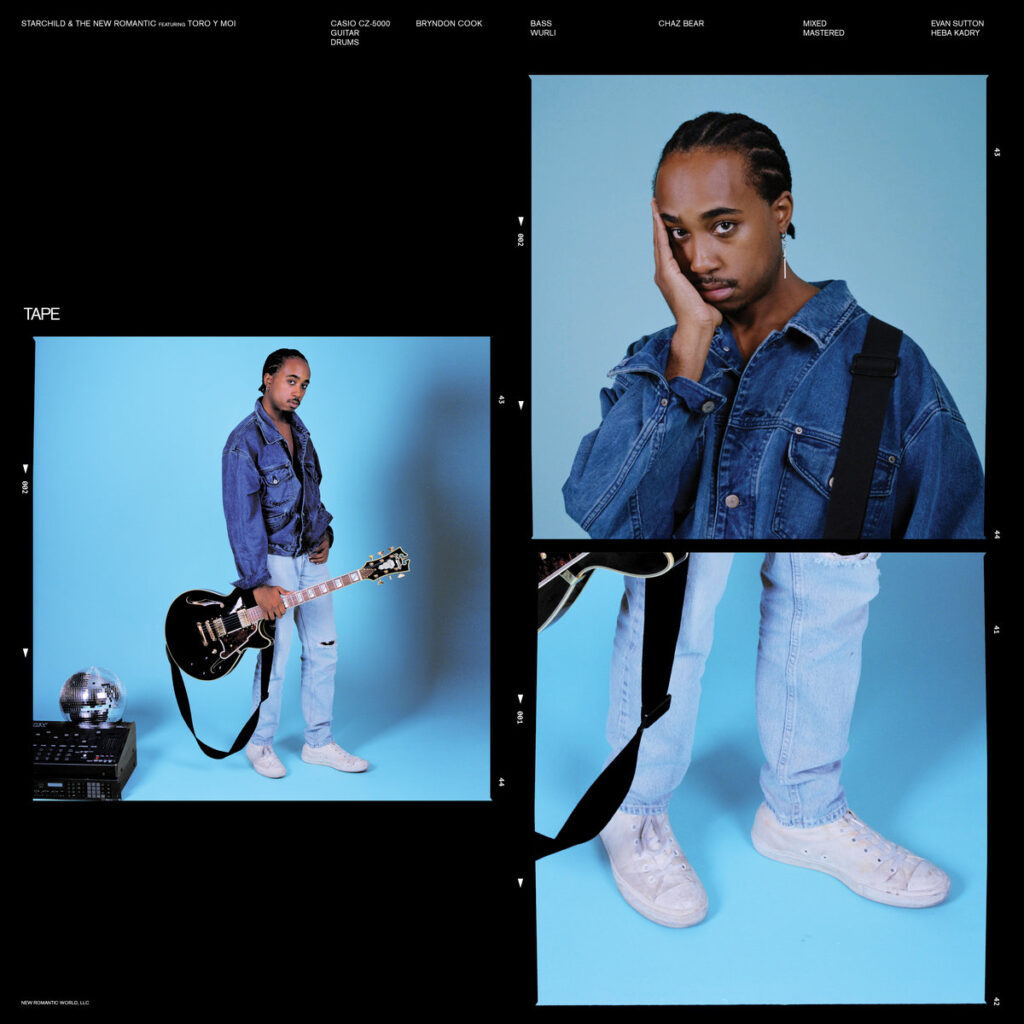

Starchild & the New Romantic is heavy on aesthetics. Following the monochrome debut (Crucial), his second and third releases boast promotional artwork (and photography) bathed in scarlet (“I was just seeing red!”), succeeded by the next pair, both immersed in this global, spacey air. From a consumer standpoint, I have always wondered what lay behind such imagery for recording artists – Is it calculated? Or is it simply this in-the-moment artistic impluse, like fuck it, I’m feeling like red today? From the radiant blue button-down he wears over his broken collarbone, to the globe seated atop a bookcase in the back, Cook looks as if he has just returned to Earth from this Forever-era universe – and with merch.

So the aesthetic question is high up on my list. “Even with the album cover – What was it with the world?”

“A lot of the experiences I had in between Language and Forever were, like . . . touring, and literally getting to travel the world,” he starts. “I had seen a lot of different relationships, relationships with my family had changed, all kinds of things.”

And it is then that I realize the fact of the matter: We will never live the exact life of Bryndon Cook. We will never see the exact sights he’s seen, nor witness the exact relationships he’s witnessed. Forever is, by all means, a translation of Cook’s world into the public understanding.

But – if anything – what applies to us is the essence of what we can hold onto.

All we can hold onto is that which never ends.

In Conversation With Bryndon Cook

SAMUEL HYLAND: I know a lot of artists tend to commit to certain lifestyles when they’re in, say, “album mode,” to get themselves in that mindset. Was there anything you did like that for Forever?

BRYNDON COOK: That’s a good question. I think for me – I don’t want to say it necessarily helps, but – I’ve written a lot of music while in the midst of traveling. So I wrote a lot of this album when I was at the end of the Seat at the Table tour, and we were traveling a lot, so I was just writing so many things. And that’s an interesting thing, because I do see that: how a lot of artists sort of have their “album mode.” But it changes for me all the time. Because I’ll be anywhere else, and I’ll deal with writer’s block- I try not to call it that because I don’t want to force anything; I like that fact that a lot of my songs come to me, which is what I prefer, a lot of my favorite songs are like that – but yeah, I think the signifier is when I’m traveling, or when I have another task at hand. It somehow seems to open up that space of things I want to say, or ways I want to express the things that I’m feeling. I think that’s how it works for me.

SH: You talked about how your music is sort of an authentic response to what’s happening in your world at the moment. Do you have a specific moment you remember where everything clicked, and you were like lemme just write this song?

BC: Well this is what I like about this record; it’s short, relatively short compared to the debut one – but every song had that moment for itself, which is really cool. And it was different for each one. For some of them, literally when my hand went to the keyboard, it just started. Mess Around was like that. Every part on it that you hear – because a lot of songs are pretty minimal, like some of the songs on Language have like 40 tracks; with this one, there’s songs where there’s only like 7 stems – every part came really organically. There were the songs like Mess Around, Runin, Cool Disco Dan, which were these moments where I picked up the guitar, I picked up the bass, and the part was the first thing that happened, and I was like that’s cool! Which is something I don’t think I’ve ever experienced on any other record- It felt really amazing. Because sometimes you get really down and you’re like uhh, I don’t know if this is for me, then these moments happen and you’re like Okay! This is for me! But then there were some songs like- with the title track, each part kept kind of revealing itself. We were spending a lot of time in New Orleans during the Seat At the Table run, I was staying at the Ace Hotel, and they often keep acoustic guitars in there. I started writing Forever there, and I didn’t know what I was saying, but I just kept saying If you see me a lot, If you see me, if you see me. So the album has some songs that just kind of came out. And then there are some songs that kind of worked their way out slowly. But Feeling, I wrote when I was fifteen.

SH: Oh, really?

BC: It’s one of the first songs I’ve ever written.

SH: Tell me about when you wrote it as a fifteen-year-old. What was that like?

BC: I don’t think I knew that much about, say, musical progressions and stuff like that- like, it’s a pretty simple song. And back then, I think I really fashioned myself as more of a soul singer. I really wasn’t a producer at all back then. I used to chop up beats and stuff on Garageband, but I hadn’t, like, written anything in crazy falsetto. I hadn’t really found my style. I think that’s why I like it so much, because it represents this sort of bedrock for me, which is soul music. But I don’t remember my headspace when I wrote it. I just remember- I dealt with a lot of depression, pretty hardcore, in like eighth grade, through high school. And anyone who knows me knows that I’m a very happy person. I like to lift people’s spirits. But I had a lot of imagination at that point, I think it came out of that.

SH: You mentioned this bedrock concept, and I want to ask about your musical heritage. You grew up in the South, which I feel automatically gives you a huge musical context, because so much came out of there – how much do you try to adhere to those roots, and how much do you try to expand?

BC: Well I’ll say, as a caveat, I have a very southern family. My whole family is from Mississippi. But me and my brothers were born in different states; we grew up in Maryland and Atlanta, which are arguably southern states- where are you right now?

SH: Oh I’m in New York.

BC: Are you from New York?

SH: Well originally, I was from Queens, New York – and one, I appreciate you asking this question – but we just moved into Long Island. Long Island is hard to adjust to, because it’s straight up white people- much less diverse than Queens was.

BC: Yeah.

SH: But I’m getting there.

BC: I’m praying for you man, that’s tough. But I mean, so yeah, we used to visit Mississippi every summer, and I grew up going to my mom’s church. And that’s very connected to us. So the way that I relate to that ethos is that from a young age, I knew a lot about my history. And not necessarily my family’s history — but Black, African-American, post-slavery, coming from sharecroppers, like- my dad is born behind a cottonfield. You know what I mean? It’s real. It’s still tangible. So I think I was always invested in this kind of ethno-musicology understanding of the journey of black music. Part of what kept me from doing music for a long time was that I was so cognizant of the rules, the history, and the gravity of this thing – especially when you grow up around people from the church: everybody can harmonize; everybody can hold a note; everybody can sing. But that doesn’t give you- it’s a very radically different mindset, because now, you buy a Macbook and everyone’s got logic, basically. A lot of people do music just because, now. But I come from a place where there’s a huge responsibility in what this is, where it comes from, where it’s left off. So when I did say to myself ‘I’m going to do it,’ I definitely was trying to uphold- and not to be didactic, I don’t try to teach anything – but it means a lot to me, and in my opinion, the people who have sacrificed the most and given the most to this thing: that’s where they’re coming from too. So it wouldn’t make any sense for me to do it and not care about it. But I know I don’t have a particularly southern sound, because I think the people who inspired me to make music, or try things out, aren’t particularly Southern or anything like that. Like, I’m not a blues musician – and keeping up with gospel players is a hard thing; I don’t take that lightly. But where I do sit with this – and I’m saying too much – but I do think it’s important to consider and maintain the reality of what this is. There’s far too many forces that are invested in erasure, and delusional self-aggrandizement. And it’s something to me that sacrifices something that is integral to the survival of an entire people. It’s just not a game.

“It’s a lot about redefining unconditional love.”

SH: That’s real. Listening to a lot of your music, I get this thing – and it may be intentional, it may not be intentional – but I get this thing about combining those R&B roots you were talking about with this futuristic backdrop. Sort of like when Parliament-Funkadelic was coming out, that Afro-futurism. What role did that play in the shaping of Forever, or just your music in general?

BC: Where do you hear it?

SH: Take Silent Disco, for example, those last few minutes when you’re playing guitar licks in the pocket – You know the song Good to Your Earhole?

BC: Yeah!

SH: With that, and a lot of George Clinton, Funkadelic stuff, you have this emphasis on the rhythm section, with the guitar being the main accent to that- but you have synthesizers. It’s like you have those roots that you play with, but it’s 2020. You know what I’m saying?

BC: Yeah. Thank you for being specific, I really appreciate that, because I find sometimes that people can use the Afro-Futurism thing generally – I didn’t think you were, that’s why I was gonna ask. But that’s a good question. I think it’s probably, like, a couple things . . . Well it’s part of the mission statement of the project to begin with. I tell people often that that’s what the name is about: Starhild represents the George Clinton lineage of funk and popular music. And what I like about it is that Parliament isn’t just Parliament history, it’s also James Brown history; it’s also Prince history. Because there’s a direct lineage from Little Richard discovering James Brown, James Brown having all of his bands going through the JB’s, and then James Brown hiring Bootsy and Catfish Collins, and then Bootsy and Catfish going and joining forces with George when they were in their psychedelic era, and then bringing them into the 70s with the kind of, like, modern funk- I mean, where we’re at now, it’s all Bootsy’s songwriting; rhythmic stuff – and then George being picked up by Prince, the levels of influence, and then how Sly Stone kind of traversed through all this. The history of it – Even all the way to D’Angelo – everyone that matters, to me, didn’t leave stuff behind: they carried on something. And I find that to be very important to the sound, and really just to the ethos. But to my sound in particular, you know, there’s that. So there’s the mission statement vibe of it, but then there’s something I also learned from Pharrell and the Neptunes. Part of the reason that the Neptunes’ sound sounds the way that it does is because they literally used what they had around. They didn’t have a guitar, so he was using the chord tritone guitar sound. So that kind of mother-of-invention thing is important to me. Um- you’re gonna take these ‘um’s out, huh?

SH: Of course!

BC: That’s my achilles heel. But I think I credit that to me just being a student of music first and foremost. I play a lot of instruments and naturally I have good key; when I was growing up, in the car, I could hear a song and be like this sounds just like this song, and later we’d find out it’s because it’s the same key, or it’s the same BPM. That’s how I got good at deejaying too. I have a natural inclination for, I think, the unity of music, and then going deeper to how that relates to me as a black person, and these gifts that we’ve given through art, and through talent, and through these gifts . . . I don’t know, it’s a part of the duty of it. It’s like- I guess if I were making Silent Disco, I wouldn’t have put subkicks on it – not to say these things are bad – it wouldn’t really fit in that space. But it’s definitely about being a student. Definitely about being a student.

SH: I respect that a lot. Because a lot of these people in the music industry, especially when they’re upstart and young in their careers, they sort of want to take the industry by charge. And they forget to learn from the huge lineage of people that preceded them. So I really respect that.

BC: Thanks.

SH: Yeah, of course. Getting to the theme of the album- one thing I noticed was that your aesthetic changed from red, to straight up blue, Earthy tones, and stuff very symbolic of the world. From the imagery in the packaging, to even the globe behind you right now- wait, is that the globe you posed with on the album cover?

BC: Yeah.

SH: Oh, that’s crazy! That belongs in a museum. But I guess the first part of this question comes at the aesthetic level. Even with the album cover- what was it with the world?

BC: Yeah, I think- because with Language, a lot of the songs I wrote when I was in high school; it came out when I was done with college and stuff like that. So the experiences I had between Language and Forever were literally touring, and getting to travel the world. I had seen a lot of different relationships; relationships with my family changed, all kinds of things- being world-weary is one of them. A lot of Language had traditional, kind of, heartbreak songs – I mean, they were non-traditional – but they all had this traditional kind of opposition. And I think on the sophomore album I had gone through a lot more introspection about myself, and, I think, family. It was just a different mindset. There were a lot of basic goals with the album, I think I’ll talk about that. One was that I didn’t want to write all of my songs in falsetto. I wanted to write songs that I could perform easier with my band. I wanted to perform songs that could age with me. And with Language, it wasn’t like I was just like (holding up a red mug) ‘red.’ I think I have a quote somewhere around Language time, where I was like I was just seeing red. I really was though. And not a synesthesia thing, not like that. But there was something about moving into this space, for this album, in my life, where I was just seeing blue for some reason. As corny as that can sound.

SH: That doesn’t sound corny at all. Really.

BC: I mean, and also on a tertiary level- my favorite artist is Prince, or Peter Gabriel; for every album there’s a new haircut, or they have a new palette. And I think that helps the audience, and the messenger too, to differentiate these phases. But also just getting older, man. Hopefully people grow- and I come from a space where both of my parents are educators; I actually come from a long line of educators. But I have this saying that like, black folk – there’s a reason why we can be super critical. Like we just survived slavery . . . it’s gonna be hard not to come out a little critical — but I hope for myself and I hope for others that as people grow, however critical they may be of external factors which are real and true, they are also as concerned, and practice finding inner peace and things like that. So there was a lot of that in Forever. And it’s a lot about redefining unconditional love, like what does that mean. Because that’s what it takes in my opinion. You have to find your inner peace at the same time that you’re recognizing traumas, tragedies, all kinds of stuff.

SH: I feel like a lot of artists don’t get asked this, and it’s usually dictated from a consumer standpoint. But what’s your favorite song on the album?

BC: Sweet! It changes, man – I’ll tell you like this: I knew I had something when I made Mess Around. That song was the first song I made with my drum machine, the one that’s on the cover. And I actually got that because it’s like a 6/8 feel; everything I’m singing is 4/4, but it’s like a 6/8 swing, if you tap into it really slow. And that’s actually something I got from George Clinton and Junie Morrison, when they wrote . . . was it . . . Not Just Knee Deep? You know that song?

SH: Which album is that off?

BC: Isn’t it off of One Nation Under A Groove? Like Round and Round and Round . . .

SH: Oh, yeah.

BC: But basically George Clinton had an issue with this song because he came up with this Round and Round, and it’s 1-2-3, 1-2-3; and Junie Morrison figured out how to arrange this 6/8 figure over a 4/4 groove so it wouldn’t disrupt the rhythm. So I think I had internalized that, and Mess Around was the first song I had wrote on the drum machine – but I got that rhythm by mistake. And then as soon as I had that going, I think the next thing I wrote was the bass part – and that was something I learned from Prince, where he used to say the key to a good groove is like- if you have a great drum groove, the bass player wants to kick the drummer’s ass, and then the keyboard player needs to kick the bass player’s ass. So I was building on each part, and I was like Okay, this is good. And then the first time I picked up a microphone, basically, what you hear (on the song) was it. It just came out. So that was the first song where I knew I had something; that reminded me of when I wrote Hangin On, or some of my other favorite songs. But Mess Around was my first favorite song . . . I think Runnin might be my favorite; I can play that forever, because that came out naturally too. But it’s tough. It changes- when I was really in my bag I was calling this album my Greatest Hits. I just love every song. Like, I’m gonna be honest with you, artists would release one song and they’re like: I didn’t always do what I was tryna do on that one. But I feel like with every song, I did. What about you, do you have a favorite song?

SH: The one I mentioned earlier definitely, Silent Disco, because I have a story about it.

BC: Oooh!

SH: Yeah, when you were playing guitar in the pocket later on – I personally play guitar at my church-

BC: Oh, sick!

SH: The pastor would always tell me I’m a bit too boisterous, or up front, with how I play. Like I’d be playing power chords, totally cranked out, all this riffage, and it would be Amazing Grace or something.

BC: Wow.

SH: So the pastor told me I had to listen to similar music before I hopped on the altar and started playing it. And I’m doing this on a Fender Mustang – which is really meant for softer stuff, like you can tell from the single coil pickups. But I’m listening to this album as I’m getting prepared for this interview, and these notes you’re playing are like little kisses, little plucks. And it’s a beat that, if I got it, I would be going crazy over. But I feel that there’s a beauty in being passive. In letting that process you mentioned with the bass kicking the drummer’s ass, and the keyboard kicking the bass’ ass really take shape, and using your instrument to accessorize. Sorry to be long about that.

BC: No! I like conversation. I didn’t know you play in the church, how long have you been playing guitar?

SH: I was in the seventh grade. I’m in eleventh now, so I think that was like four years. But it was my first time being in a real record store, and I was seeing all these album covers, so I wanted to listen to those albums. I ended up listening to Jimi Hendrix’s second album – Axis: Bold As Love, I think it’s called – and I heard that solo at the end of the title track, where it sounds like the guitar is flying.

BC: I love that song.

SH: Right? It was the first time I realized that you could create something with guitar. So I begged my parents to get me that little starter pack, with the Squier and the Frontman Amp- and it was fun. That’s when I started playing – When did you start playing?

BC: Similarly- well it’s not my first instrument, I’m a tenor saxophone; I still have my first tenor saxophone. But, what was it, like fifth grade? My oldest brother had a guitar, like a Spanish acoustic, so we always had a guitar in the house. And I think similarly to you I started listening to music that had that. I was a little late to Jimi Hendrix I think, maybe by a few grades . . . I was getting into John Mayer, unfortunately.

SH: I mean, there’s credit to that.

BC: As soon as you get into John Mayer, it’s like, impossible not to get into Jimi Hendrix. Once I started really liking Prince – because I was a Michael Jackson diehard, I didn’t want anything to do with Prince – I think I discovered that I was autodidactic; I liked to teach myself songs and things I liked. So I would just keep a guitar in my hands, and I started learning things that, later, I would find out were theoretical, but I just got my own natural sense to. This actually might answer the question about Silent Disco, because here’s the thing: a lot of people, when they get a guitar, it has become so much of a ‘shredding’ thing that that’s where they go to first, but you know the first thing I taught myself when I got my first electric guitar?

SH: What?

BC: It took a long time, but the first thing I wanted to play was the riff from Freak Out, from Chic.

SH: Oh, yeah!

BC: That’s my wheelhouse, rhythm guitar. It took me a while to learn how to actually like shred shred – which I can do now – but that wasn’t my thing: it was playing in the pocket, you know?

SH: And that’s something that you get with the value of not going to conventional guitar classes. Waking up like Aw man, I have to go to guitar classes again, I have to learn scales – I mean there is a value to that, but I feel that when you listen to music and try to emulate what you’re hearing, there’s so much more. And it’s authentically informed by all of your influences.

BC: Well that’s this thing- I had this thing where I would come home, go downstairs and amp up, put on a Parliament record, or Rick James’ greatest hits, or a Stevie Wonder record, and try to learn the parts to play along with. Because I had this whole imagination thing, where I thought it was going to be my ticket out – which it was, in a sense – but the thing was, like, I was learning people’s whole catalogues, because I was like If they ever needed me, I would know how to play all of their songs immediately. That’s kind of what helped me get into Solange’s band, because I was such a big fan of Lightspeed Champion and the early Blood Orange stuff, that when they started working, I already knew those songs. So when it was time to audition, I was like Yeah I know how to play Bad Girls. I mean, and you play in the church; you know how that is – like, people know a thousand fucking songs. In every key. But that was kind of my hobby, kind of my thing.

SH: Yeah. You talked a lot about what it is from a producer standpoint, what you got out of the album, what you were trying to portray. When a listener puts on their headphones and listens to Forever, what do you want them to feel when the final track fades out?

BC: What’s funny is that the E.P before it, VHS, they were kind of in one. There was a period of time when Tape was going to be on VHS – that’s why it’s called Tape – It was going to be one record, but then it became two. So I spent a lot of time on the track listing for Forever . . . and honestly, when I went into it, you have to remember that this is an early post-Blonde world. Like, Frank Ocean Blonde. And Blonde is a great record, but there was something that was going on – and still going on – where everything I heard sounded like ‘listens-to-blonde-once’. And there was something about that that felt cheap. But also disrespectful to Frank Ocean in the first place. I’m like I don’t think this is what he wants with this. Just being like I’m gonna drown my guitar in chorus and put it in the front – which is fine, but not me. So I was really eager to figure out how to take my sound and my ethos, which is admittedly steeped in a lot of the past and understanding of history, like I said, and interested and curiously invested in how do I make that sit in the present tense. And I wanted people to hear that, not be afraid of that, and it to make sense. With a lot of the feedback I got early on, people were like it sounds like you. Not that the last albums didn’t, but this album sounds like you talking to me. And I was like cool! Which isn’t something I planned; I don’t think it’s something you can plan necessarily, but I did want it to feel like when you hear it from top to bottom it sounds like one full track. Doing the singles releases was interesting and difficult. A lot of people came back to me, and were like Oh, once I got to hear everything in context it all made sense; and I was like good. But I think it was just that. There’s part of me that’s really stubborn about maintaining stuff that, for some reason, people want to run away from so much. I understand the discourse about ‘destroying genres;’ you know, a lot of my peers want to be ‘genre-less’ – that’s cool and all – but a part of me in my heart that’s like when did soul music become a bad word? When did funk become a bad word? That’s why there’s two songs with disco in it, because it’s all black music, and it can be live and direct right now; you don’t have to project what you think onto it. And I’ll show you. So there was that, and it also has to do with what the title is, because that’s an indefinite thing in my mind – and it makes me quite emotional. It’s ironic because I didn’t really get a lot of press, which makes me feel different ways on different days. With the first two records, I got to hear a lot of feedback that I felt was very cheap. Like, sometimes people would be like Oh, it sounds like Prince. And I’m like . . . okay? That tells me two things: you don’t really know Prince, because Prince sounds like a million things, and secondly, that’s not a bad thing, nor is it easy.

I mean, I like The 1975, but they’re good. You’ve got enough space on your page to talk about us.

SH: it’s not a casual thing that you can just say.

BC: Yeah, or make, you know? Like, I’d like to see you do it. It takes hours. It takes years and years of being a student of these vessels. But I’m getting far away from the point.

SH: Oh, no. Keep going.

BC: I was getting a lot of these write-ups where it was like he-sounds-like-Prince blah blah blah, like I’ll show you what else there is, you know? So I think it was that kind of thing, like when I made Mess Around, I was like okay. Silent Disco, I was like okay, that’s what I’m talking about.

SH: I don’t think I got to read it in-depth, but you know how Pitchfork does the five-albums-you-need-to-listen-to-right-now series, or something like that? Did they say that you sounded like Prince in that? Because I didn’t get to read it through.

BC: Nah, they just said ‘Bryndon Cook is Starchild & the New Romantic,’ and listed the features and all that stuff. But no review.

SH: I’m shocked that this wasn’t eaten up by the press. I’ve heard worse albums that have at least gotten reviewed, it’s crazy.

BC: Oh, you don’t even know the half of it. I was tweeting yesterday that from April to July, I was hunting down press- because, you know, I’m independent; I don’t have an agent, I don’t have a manager. I tweeted, I think I know verbatim: from April to July, I got turned down from press quite often, because – I would hear this quote – publications were ‘focused on Black Lives Matter.’

SH: But that doesn’t make any sense.

BC: It’s delusional. And I had to combat that so often, with people I was afraid to lose relationships with, and I would say to them foremost: they don’t know how insulting and delusional it is to tell an independent black artist that is offering their work- and to places that have written about me before, or whatever it may be – because I’m a life that matters, no? Like, where is it in your practice? And a lot of people, in their response to me, have been like Oh, these things don’t matter, and these blogs – they’ll be like ‘fuck ‘em.’ And I get that, but at the same time, it’s like- these things mean a lot to me for posterity. And consistency, and all kinds of things like that. I saw this article that got written about me when it came out; it was written in French, and I translated it, and the first sentence broke my heart. Because it really showed me how important press is for promoting – and I don’t like promoting and marketing as much as I like making, but it’s a necessary evil. This article that I translated: the first line said: “We would not have known about this album if Aaron Maine of Porches didn’t put it in their Instagram story.” And I love Aaron. Aaron’s like, one of my best friends in this whole game. But I was like wow, isn’t that something. I’m at the mercy of my friends putting it on their IG stories. And the industry would have you think Bryndon, if you had a manager, if you had a publicist, someone who’s in between you and the publications, that’s the way that they like- that doesn’t make sense, because we’re just human bodies. I’m the person who made it, and I’m being direct to the source. So it actually doesn’t make sense – and I have a journalism background, too – it just doesn’t make sense that these places Wax Poetics like that. Everybody’s trying to posture now – and I don’t want to say everybody, because there are people out there that are really doing the work socially – but these brands, or whatnot, everyone’s trying to pivot or posture to the current time. But behind the closed door – or behind the email threads – brothers are still getting ghosted, black work is still getting passed over . . . For what? I mean, I like The 1975, but they’re good. You’ve got enough space on your page to talk about us.

But behind the closed door – or behind the email threads – brothers are still getting ghosted, black work is still getting passed over . . . For what?

SH: I’ve never really thought about it like that. Because you have this whole image going on, where there’s so much performative ethos swirling around – let’s say a company changes its profile picture to a black version of their logo. They’re like Oh yeah, we stand with black lives. And then you have an independent black artist offering their work – but ‘we can’t accept that, because black lives matter.’ That doesn’t make sense.

BC: It’s like ‘We’re focused on black lives matter, and the protests’ – I mean, at least be consistent. Because these places have wrote about me or reviewed me in the past, like I said. So it’s not like I was barking up new trees. And it’s like- when I was nineteen I interned at Pitchfork.

SH: Oh, for real?

BC: Yeah, because when I came to New York I went to SUNY Purchase, their Acting Conservatory. And after my sophomore year, I decided not to go home because I wanted to stay in the city. So I did three things: I was doing Shakespeare somewhere in the city, I was working at American Apparel, and I also was interning at Pitchfork. It was ironic, because when I would connect with these folks – a lot of these people know me on a first-name-basis. A lot of it was disheartening, because I was fortunate enough to be around some friends – and I’m not even someone who shares a lot; I don’t like to talk about my plans until they’re done – so doing this album as a features album was kind of a thing. It was sort of a challenge for myself. Because people who don’t collaborate get scared, like I don’t want to lose my sound or my identity. There was a lot of this process where I was trusting people to come into my space. And all these things, you think would bring people in and whatnot. So it was a very jarring experience to get a lot of radio silence. But I’m happy to talk about it, because it’s just transparency with how this place works. Like, this album could have come out last year.

SH: Right.

BC: No, it’s been done for that long.

SH: Oh, for real? You finished it in 2019?

BC: Oh– well that was also a thing where, like, Language came out in 2018 and I wanted to try to follow up quick. So I actually was done with it, and I was shopping it around. I didn’t wake up and choose to want to put out an independent album, you know? So there was a lot of, like, I don’t want to say rejection, but taking this thing around. I mean, that’s why it’s very fulfilling and warming talking to someone like you who appreciates it. Because there was a long time when I felt like a lot of