🌐🌐🌐

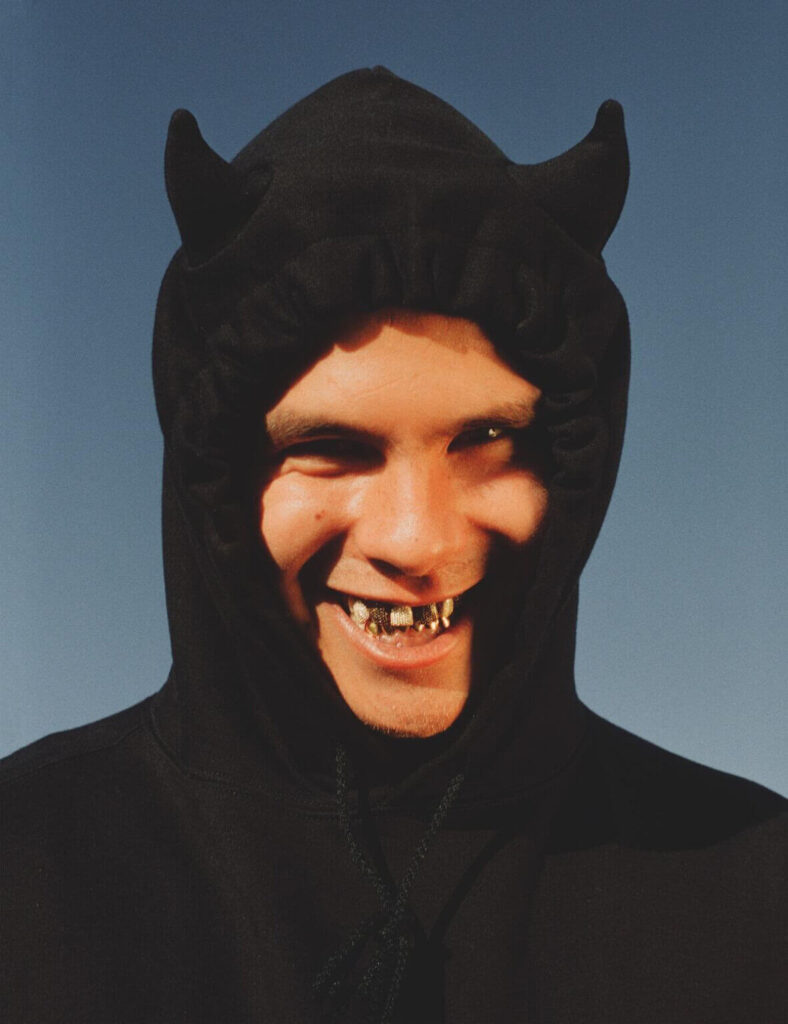

Slowthai: How Much Is Too Much?

A great deal of Slowthai’s stardom can be traced to his over-the-top antics. His eccentric act, however – complete with award show brawls, profanities hurled towards Queen Elizabeth II, and misogynistic drunkenness – places him on a fine line between marketability and outright flagrance. When does the tightrope wear too thin?

SAMUEL HYLAND

At 2020’s annual NME Awards show, the controversial UK rapper Tyron Frampton – better known as Slowthai – swaggered onstage to accept his prize for “Hero of the Year.” Up to that point, Frampton had thrown himself head-first into a unique heroism cloaked in villainistic garb: his debut album Nothing Great About Britain was packed with scathing criticisms of a government bubbling with civilian unrest (“I will treat you with the utmost respect only if you respect me a little bit, Elizabeth, you cunt,” he scowls in the opening track); he drew harsh condemnation for an on-stage gimmick that saw him perform with a fake severed head of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson; and he raised – and still does raise – eyebrows for being vocally prideful of his British background whilst at the same time being willing to burn the Union Jack at any given moment.

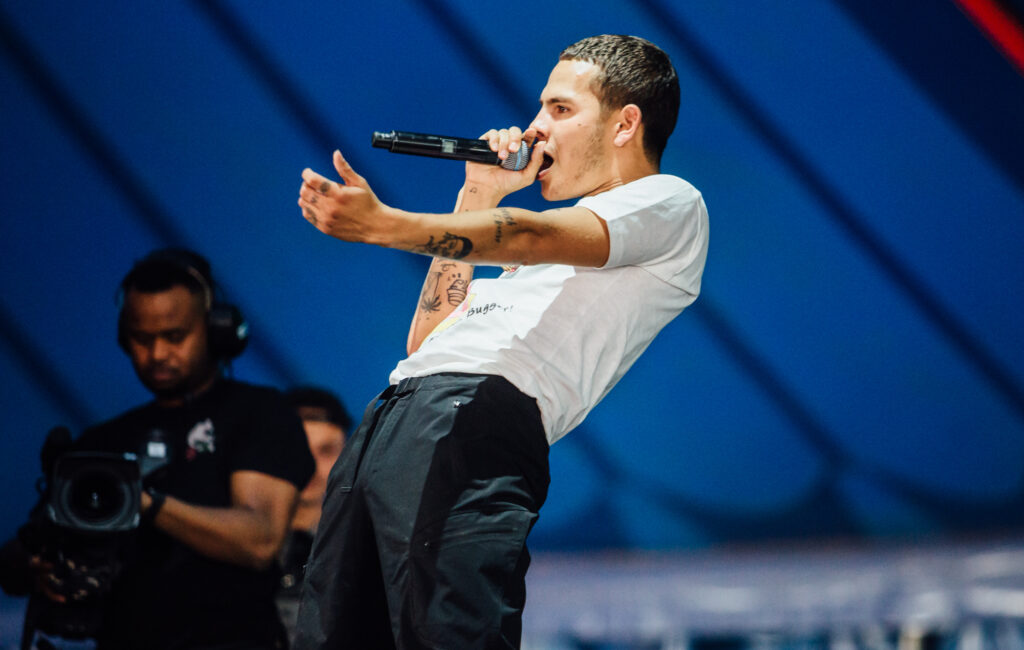

At the NME Awards, though, the problem was none of these things – it was that he was drunk. Very drunk. Drunk enough, in fact, to stagger his way stageside to presenter Katherine Ryan, and get far enough into her face to make it more of a faux-intimate moment than the comedy sketch it was originally intended to be. As the two exchanged strikingly explicit banter – one apparently playing along, and the other completely serious – Frampton remarked, holding her tightly by the waist: “Baby girl…if you want to do something, see me later…you ain’t never had anyone play with you like I’ll play with you.”

After his subsequent acceptance speech was tarnished by a loudly booing crowd upset with his misogynistic display, footage on social media (any TV cameras were long cut out by then) showed him scolding the audience – Thank you for ruining my speech – to which they responded with an even more violent onslaught of boos. He tossed a lit cigarette into the front row, yelling into the mic “(This is a) Fucking wasteland.” Two crowd members hurled wine glasses at the podium. Slowthai threw his drink back into the seats. As his hit song Doorman began blasting over the speaker system, he jumped off of the stage, lunging at a man with glasses as a melee of security guards and bystanders alike desperately tried to whisk him away.

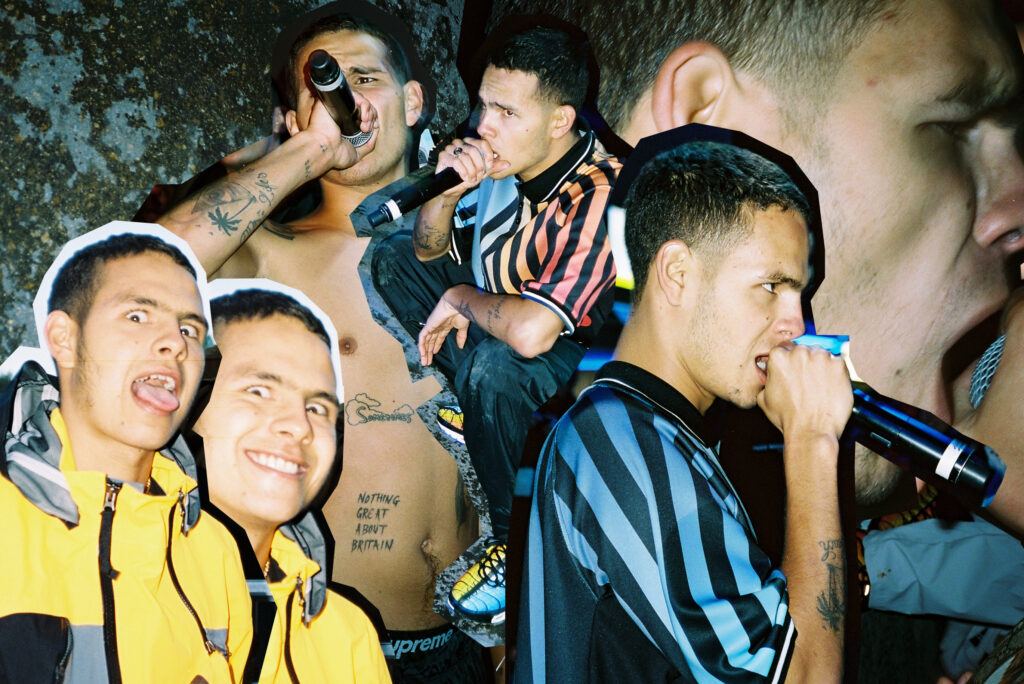

Given Slowthai’s past, flare-ups like this one come as no surprise. Born in Northampton to a single mother of Irish and Barbadian heritage, his formative years were packed with days of making mischief and prioritizing fledgling rap skills over conventional education pursuits. (The habit came to a halt when his mother was forced to attend a compulsory court hearing because Frampton spent too many school hours laying down tracks in a friend’s nearby makeshift recording studio). After being dismissed from Northampton Academy in 2016, he kicked off his full-time hunt for the music industry by releasing a set of now-removed singles on Soundcloud. The following year, he collaborated with the indie record label Bone Soda to release his debut EP I WISH I KNEW, followed by another EP titled RUNT, both leading up to his critically acclaimed inaugural LP Nothing Great About Britain. As of right now, he has a three-track tape out on streaming services, soon to be followed by his second album due out on February 5th.

The release of Slowthai’s newest single MAZZA – a relentless rave in which he boasts about ambition alongside A$AP Rocky – embodies the 26-year-old’s placement in an exclusive class of UK rappers who have been able to intrigue American listeners just as effectively as (if not more than) the home crowd. Although his U.S. following can be traced in part to recent collaborations with BROCKHAMPTON and Tyler, the Creator, a more compelling through-line can be drawn to the way he has chosen to merge politics with his artistic output. For comparison’s sake, Skepta, the veteran MC hailing from North Tottenham, London, is undoubtedly the first to cross one’s mind when it comes to dual hip-hop citizenship like Frampton’s own. When it comes to politics, though, he is notoriously tight-lipped: dodging interview questions about reigning Prime Ministers, raising eyebrows for a completely random Tweet containing an image of British Parliament member Priti Patel, and even infamously covering his ears when confronted with race-related subject matter at his 2018 GQ cover shoot interview.

“He’s too tough to see himself pied in the face, but he’s equally too disconnected from remorse to be exempt from the pie indefinitely spewed by his persona.”

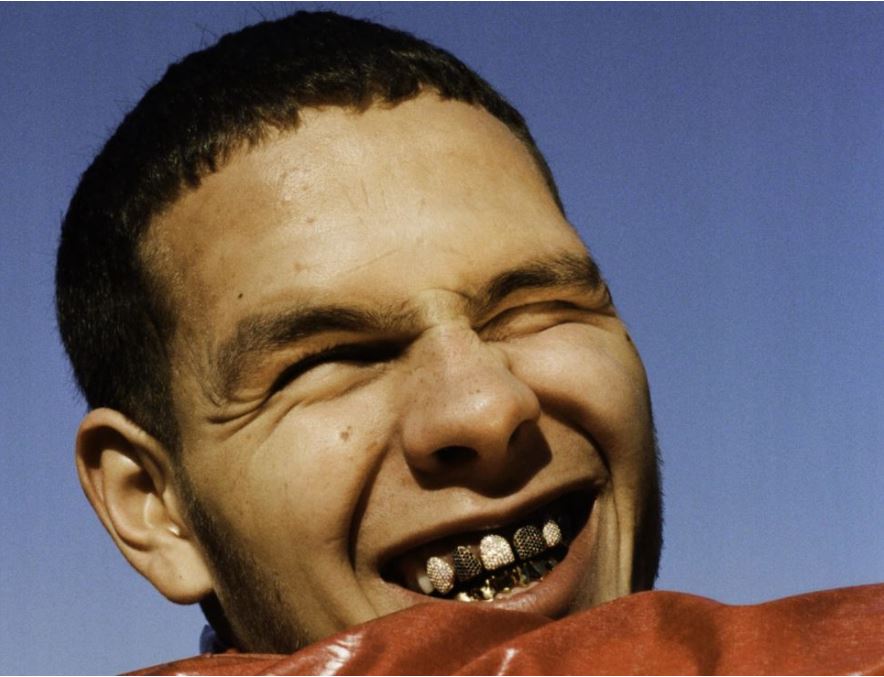

Slowthai, on the other hand, takes politics from a brashly opposite angle to that of his American peers. Whereas listeners in the U.S. have grown accustomed to artists seldom channeling politics unless it’s to either get out the vote or back social justice causes, Slowthai has built his entire artistic mantle upon the rock of anti-establishment rhetoric. Taylor Swift can still be Taylor Swift without being vocal about political inclinations; Slowthai is nothing without being boisterous about hating the government. And inasmuch as hatred for the government lives en masse as a silent undertone in cluttered underground rap scenes, Slowthai’s particular loudness about it is what sets him apart from the typical inner-city kid afraid of social repercussions. Anyone can rap out of anger towards society – but those that can rap both out of and about anger towards society simultaneously channel passion and invoke it. International influence requires one to do both. Slowthai’s villainous approach to British society is wholly epitomized by his response to an NME interviewer, upon being asked what he thought listeners found compelling about his anarchistic debut album: “I think people just found something that they agree with,” he said, flashing a silver-toothed grin amid bliss that was very likely marijuana-induced. “And if they didn’t agree with it, they can fuck off.”

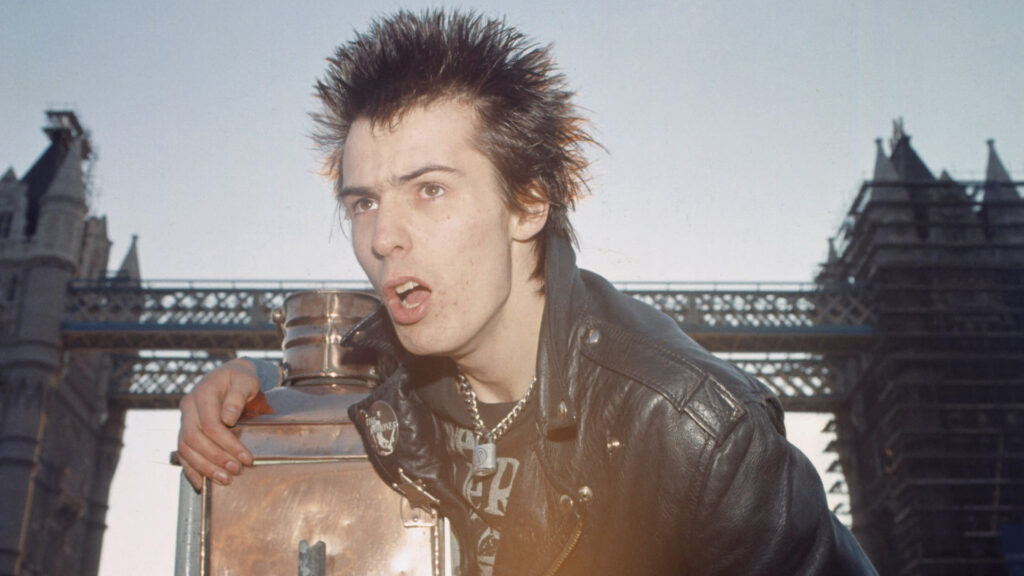

The cover of Nothing Great About Britain features a nude Slowthai set for execution in a revolutionary-era guillotine, with floors of citizens looking on from the windows of an apartment building behind him. Not embarrassed about his vulnerability, nor fearful of his fate, he flashes the same silver-toothed grin to the camera whilst forming a number six with his cuffed hands. In Nothing Great About Britain’s Guardian review, the image is likened to a famous 1977 photograph of Sex Pistols frontman John Lydon, faux-crucified, sneering into the camera with similar unapologetic intensity. In each case, the artist in question simpers not in the face of merely a lens, but that of a government system: they know that those in power are aware of their insurgency – insurgency that, in the country’s past, earned one the fate Slowthai appears to await on his album art – yet even with the prospect of an entire country awaiting their being made examples of, both embrace that smiles produced in face of futility are ones guaranteed to live beyond any initial martyrdom, mortal or reputational, cultivating the defiance.

According to the late rock music critic Lester Bangs, such willingness to surrender one’s dignity, especially given the choice to preserve it in front of an audience, is the crux of the interaction music ought to predicate itself upon. In his essay Of Pop and Pies and Fun, he berated figures like the Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger and Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant for preserving a toxic, godlike relationship with starstruck fans rather than establishing the kind of level playing field that makes music relatable enough to be substantial. Although the essay was primarily about Iggy Pop, the first example he cited of such interactive musicality was an anecdote about Alice Cooper. While performing at a concert, the singer had a cake thrown in his face by an impatient fan who yelled “So what?” after a few repetitions of a chorus. “So there he was: Alice Cooper, rock star, crouched frontstage in the middle of his act with a faceful of pie and cream and clots dripping from his ears and chin,” Bangs wrote in the essay. “So what did he do? How did he recoup the sacred time-honored dignity of the performing artist which claims the stage as his magic force field from which to bedazzle and entertain the helpless audience? Well, he pulled a handful of pie gook out of his face and slapped it right back again, smearing it into his pores and eyes and sneaking the odd little fingerlicking taste. The audience said not another word.”

To relate Cooper’s pie incident to Slowthai’s meltdown at the NME Awards is to uncover fully the duality of Bangs’ dynamic. On one side, Frampton is indubitably in the category of Mick Jagger and Robert Plant, in that he’s so committed to preserving the master-servant hierarchy between producer and consumer that he’s willing to throw a pie – in this case, a wine glass – back at any audience member who throws one first. Yet, on the other end of the stick, Slowthai is a great deal more willing to smear the pie in his own face than he makes perceptible: from walking onstage a drunken mess, to making lewd sexual propositions of Katherine Ryan in front of a sold-out O2 Arena, to lunging into his crowd to incite an all-out brawl, the sheer depth of Slowthai’s willingness to make a fool of himself beyond what artists of his caliber have been known to emulate is the essence of his peculiarity. And aside from his political ramblings, it is this very dynamic that lugs his intrigue up from the United Kingdom and into the United States.

A rapper like Drake, placed in Slowthai’s NME Awards situation, would likely hurl his drink into the audience and leave it at that, all further courses of action purged for the sake of his reputation. A rapper like Tyler, the Creator, given the same predicament, would do something along the lines of manically laughing at himself. Somehow, whether intentionally or unintentionally, Slowthai finds himself in the middle section of music’s most explicitly two-sided venn diagram: He’s too tough to see himself pied in the face, but he’s equally too disconnected from remorse to be exempt from the pie indefinitely spewed by his persona.

What sets Slowthai apart, yet, is that unlike artists like a young Chris Brown or a Whole Lotta Red-era Playboi Carti, who deliberately sought to fill cultural craters left by the likes of Michael Jackson and Iggy Pop, the only aspect of history channeled in his output is the part of it that makes him upset – Britain – and just as it was for John Lydon, the outcry that Nothing’s Great About it is one made angrily enough to echo worldwide.

John Lydon, the Public Image Ltd. frontman who posed for the aforementioned faux-crucifixion shot, related to Frampton further in this sense that no stage was a barrier between his act and his followers. The story is one told over generations of rock banter: the Sex Pistols were falling apart. In the few months that spanned between their magnum opus Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols and their fateful string of final performances, all that could go wrong did – they had been infamously pitted against each other by manager Malcolm McLaren, toxic groupies put members onto near-fatal heroin addictions, and nearly every penny made from a chart-topping debut album slipped through irresponsible fingers en route to virtual destitution.

But today – despite coughing up blood via a terrible mixture of heroin and influenza – Lydon had a capacity crowd of over 5,000 Americans to entertain. And when they wanted an encore, an encore is what he gave them:

“You’ll get one number and one number only, ‘cause I’m a lazy bastard,” he said into the microphone.

The number promised was a sloppily improvised cover of the Stooges’ No Fun. By the final cymbal crash, amongst various other made-up lyrics, Lydon added: “This is no fun. No fun. This is no fun—at all. No fun,” his familiar sneer and tired eyes purporting that he meant every word.

“Ever get the feeling that you’ve been cheated? Good night.” He threw down the microphone and walked off stage. The Sex Pistols were over.

In previous years, the Sex Pistols can be considered to have pioneered the class of British-American stardom Slowthai now finds himself cloaked in. And in achieving such status, similar on-stage antics to their public breakup were not the only measures by which Americans found them fascinating: Just like Tyron Frampton, they hated every bit of the system. And they were loud about it.

In 1976 for instance, featured on the British primetime television program The Today Show, they drew loads of angry phone calls along with hordes of media criticism for a highly controversial interview with presenter Bill Grundy, in which the band gave profanity-laced one-word answers behind billows of cigarette smoke, snobbish young women standing at hand – wrapping up by calling Grundy a “dirty bastard” and a “fucking rotter.” (Grundy had offered to meet one of the young women after the show, after she expressed during the interview that she had always wanted to see him in person. The gesture was taken as a sexual rendezvous). Afterwards, Grundy was fired by Today.

The following year, too, they released their most controversial single to date at that point, God Save the Queen. With the track boasting overtly critical lyrical content (“God save the queen/She ain’t no human being/And there’s no future/In England’s dreaming”), dissent, of course was a given amongst British conservatives – but as if the amount of feathers already ruffled had not been enough, they strategically scheduled the song’s release to coincide with the pinnacle of Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee celebration. Then, after it sold over 150,000 copies in less than two weeks, the band’s since-disgraced manager Malcolm Mclaren arranged for the chartering of a private boat, planning to have them perform the song on River Thames whilst passing Westminster Pier and the Houses of Parliament over Jubilee weekend. The ship was forced to dock by police, and a violent arrest ensued.

Just like it works for Slowthai, such thick anti-establishment coating was a major factor in American youth adopting a fondness to the Sex Pistols. After Lydon’s band drew international intrigue – a mix of both praise and criticism – for their mild-mannered debut LP, along with various other less-than-favorable antics, a considerable wave of similarly rebellious punk groups began populating the United States. Not too long after the initial wave, following decades of pop music predominantly consisting of “jive” solely meant to get one’s body moving, the vast majority of those newly formed groups had built themselves entire reputations upon anti-establishment rhetoric. The means by which one musically commented on political causes saw itself permanently skewed: over years where the Vietnam War proved to be America’s most pressing social issue, somber ballads like John Lennon’s Imagine and Bob Dylan’s All Along the Watchtower sought to cultivate campfire-esque togetherness worldwide, with protest songs generally taking after the peace they advocated for – but with bands like the Ramones, came ear-splitting, aggressive, forceful songs like I’m Against It (essentially a brashly delivered list of things Joey Ramone disliked, some of which include Jesus freaks, the Viet Cong, and waterbugs). With bands like the Misfits, came harrowing, subliminal, cultural criticisms like Hollywood Babylon. And with bands like the Stooges – of course – came intense, Vietnam-inspired selections like the rambunctious Search and Destroy.

It is far beyond a longshot to claim that Slowthai is fueling his own anti-establishment movement in the United States, or changing the way American MCs express their grievances. The crossroads at which Slowthai and the Sex Pistols separate is one split between inciting new rebellion overseas, and solely bringing existing rebellion to a new location — Slowthai finds himself on the latter pathway.

But it is equally beyond a longshot to overlook the innocent, unintentional genius with which he navigates the uphill climb ahead. In the aforementioned Guardian review of Nothing Great About Britain, critic Alex Petridis is apprehensive about likening Frampton to notorious troublemakers of old, citing that “Mentioning the Sex Pistols in the same breath as a young artist is right up there with referring to someone as “the new Dylan” in the damning-by-association stakes.” What sets Slowthai apart, yet, is that unlike artists like a young Chris Brown or a Whole Lotta Red-era Playboi Carti, who deliberately sought to fill cultural craters left by the likes of Michael Jackson and Iggy Pop, the only aspect of history channeled in his output is the part of it that makes him upset – Britain – and just as it was for John Lydon, the outcry that Nothing’s Great About it is one made angrily enough to echo worldwide.

Of course, widespread social media condemnation followed Slowthai’s violent NME Awards show outburst. Amidst the firestorm, he took to Twitter to apologize, tweeting later that night: “@nme please forward my award to @kathbum for she is the hero of the year. what started as a joke between us escalated to a point of shameful actions on my part. i want to unreservedly apologise, there is no excuse and I am sorry. i am not a hero. (1/2).” In his next tweet, he addressed Katherine Ryan directly: “katherine, you are a master at your craft and next time i’ll take my seat and leave the comedy to you. to any woman or man who saw a reflection of situations they’ve been in in those videos, i am sorry. i promise to do better. let’s talk here.”

But if there is anything the international audience he has garnered is aware of to this point, it’s that all endgames of his antics fall into one of two categories: consequences he can evade, and consequences he cares too little about to stop what he’s doing. Neither has gotten him to shut up just as yet.

The argument cited by many in Frampton’s comment section was that this was not something he could simply walk away from. Whereas for Frampton, it was a matter of simply apologizing and moving onward with his career, for the vast numbers of women who either had been or would be subjected to such traumas as the ones he invoked onstage, the incident and its implications were not nearly as forgettable.

For Katherine Ryan, however, that night’s Twitter activity struck a far different tone: In her first tweet about the matter, she noted that he had not made her uncomfortable, going on to cite a need for more female representation in media. In her next address of the topic, she replied to a concerned follower that “he was fine. I’m the kind of woman he can say whatever he likes to!”

Both musically and in the flesh, Slowthai seems to fit everyone underneath the same umbrella of fair game – whether it be a presenter at the NME Awards, or the reigning Queen of England. But if there is anything the international audience he has garnered is aware of up to this point, it’s that all endgames of his antics fall into one of two categories: consequences he can evade, and consequences he cares too little about to stop what he’s doing. Neither has gotten him to shut up just as yet.