Skepta, A$AP Rocky, and the Futility of Black Genius

How the concept of black genius ensnared creatives of color for centuries, with the help of consumers who – in apparent goodwill – only made the situation worse.

SAMUEL HYLAND

At one point in the interview that accompanied Skepta’s viral unclad GQ cover shoot with then-girlfriend Naomi Campbell, the London MC was asked a question about politics: How has Donald Trump’s presidency affected you?

Campbell was first to offer a response. “Those people that are ignorant,” she said, stone-faced and stern, “Feel now that they can come out openly and show their ignorance. Because the leader of the free world is showing his.”

But on the far end of the two-cushion couch they shared, Skepta sat, cool and aloof. He fiddled with his hands as a smug grin crept onto the corners of his lips; boasting the kind of quiet swagger that epitomized his ascent to global prominence, he leaned back in his white bathrobe, awkwardly eager for the conclusion of his counterpart’s spiel.

Campbell’s face scrunched as she continued.

“I can’t deal with-”

“Are we talking about politics?”

“Yeah, I don’t really want to get into politics-”

He shoved two pointer fingers into his ears. A sarcastic grimace replaced his smile. Until Campbell placed a hand on his knee and promised him that she wasn’t “going to go there,” he stayed that way, later stealing a jesting peek at her as if to check whether the coast was clear.

It was not.

GQ’s next question was, perhaps, more political – and as the premiere musical presence in the room, it was Skepta’s question to answer.

How much racism is there in the music industry?

Now – though in no way removed from his trademark chill – there was the impression that he was a deer in the headlights. The hands that, mere seconds ago, blockaded his ear gates from the very mention of global affairs, now moved in strange patterns before him, signaling in abstract substance as if he was groping for answers in mid-air.

“On one stage, whites were racist to blacks, but now rappers are saying in their songs (things like) White bitch, she sniff a line – it’s like . . . why can a black rapper say that?” he started.

As he said this, a deliberate camera cut showed Campbell glaring onward with semi-squinted eyes. (“Naomi’s faceeeee when he was talking his foolery about racism💀💀💀,” one Youtube commenter said). Her face did not appear to change for the duration of Skepta’s response.

“If a white rapper said black bitch – and she’s the most beautiful precious diamond in the world, not even in a derogatory way, put the most beautiful flower on the end of it – he would get crucified for saying that. I think everybody deep down knows wrong and right; some people being racist know they’re being ignorant.”

Much of what discussion took place on social media following the video’s release came as sharp criticism to Skepta’s apparent nonchalance. Many cited various elephants in the room gone unaddressed: tendencies of black male rappers to diss black women; normalization of colorism in popular culture; the ever-increasing rarity of black male celebrities dating black women in the UK, etc.

Yet, the premiere reason for which the judgment never exceeded a one-day trend was that it was no surprise. For his entire career, Skepta positioned himself as far away from the gamut of political activism as possible: dodging partisan interview questions, keeping most lyrical subject matter strictly personal (up to 2016’s Konnichiwa), and of course – in a way that somewhat embodies his approach to the entire matter – covering his ears at the mere inkling of conversation gone civically engaged.

Years later even, when he tweeted a candid image of the British Parliament member Priti Patel out of poorly-received cryptic randomness, one of the many tweets that came in response read: “Wasn’t (sic) this not Skepta when Naomi Campbell was talking about politics in that GQ video? Should we even be surprised at this tweet?” The media attachment was an image of Skepta with his fingers in his ears, closing his eyes, waiting for the subject to pass over. Of the fourteen users that retweeted the message with comments, none were remotely shocked: It’s Skepta – What was there to be surprised about?

Something had to give reason for the fact that criticism was incurred in the first place, despite there being no probability of any profound answer to a question he spent his entire career avoiding. That thing is the unconditional expectation of black genius from artists of color.

In a New Yorker essay by the ex-Pitchfork writer Sheldon Pearce, the essence of black genius is examined through the lens of Marcus J. Moore’s recently published book on the concept.

“They ‘spoke to us and for us’,” Pearce cites from the text. “They created music in which we could see our full, beautiful selves, and they helped us remember that we aren’t second-class citizens, even when the world tried to render us invisible. America can beat you down if you let it, but through Sly’s howl, Curtis’s falsetto, and D’Angelo’s hum, you felt the beauty and bleakness of black culture.”

The period Moore refers to in names mentioned is a period in which funk music, under the wing of George Clinton, swept onto the music scene, bringing a black subculture and adjacent afro-futurism into the permanent cultural limelight along with it. Acts like Parliament-Funkadelic and the Ohio Players broadcasted a hereafter that consisted of black faces poking out of glistening metallic armour – Black astronauts leading charges to extraplanetary nations not accessible to people who weren’t down wit it – black eccentricity superseding what oppressive box was imposed by American tradition.

Today, modern examples of black genius include Childish Gambino’s symbol-heavy music videos for This is America and Feels like Summer, Pink Siifu’s 2020 LP Negro, and, by some measures, Joey Badda$$’s 2017 protest album All-Amerikkkan Bada$$. The defining distinction of black genius that binds each production together is described by the Roots drummer QuestLove as lingering survivor’s guilt felt by victims of African-American oppression that have made it out: a guilt that influences them to translate such pain into art, once given a platform to vindicate those ensnared in the trenches for life without option to find refuge in a studio.

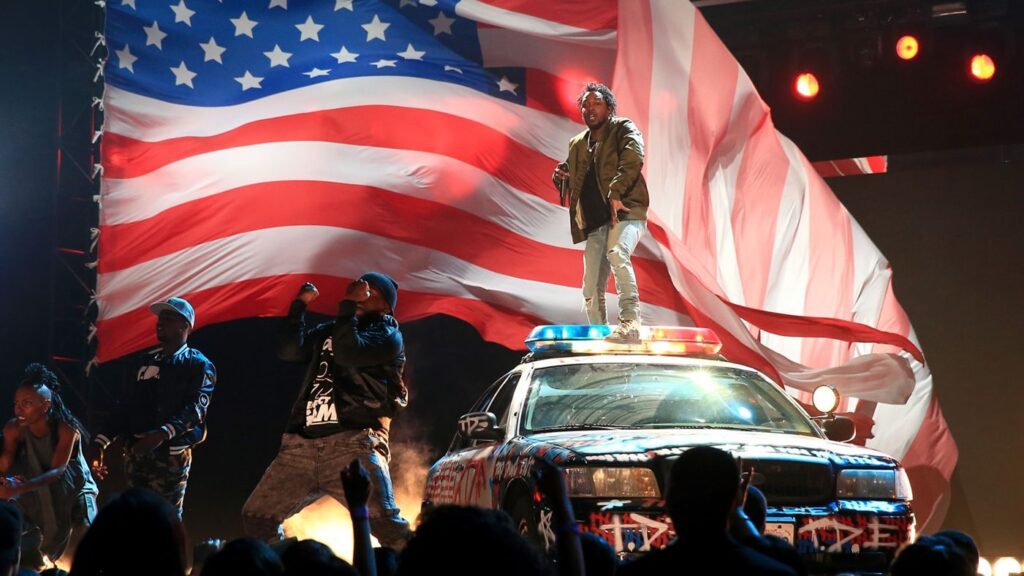

Kendrick Lamar, Pearce writes, is the primary artist of his respective generation to be anointed with such a mantle. Similar to figures like Clinton and Bob Marley who donned it in decades past, Lamar earned the headline by exploring new crevices of Afro existence over the course of a still-young artistic lifespan, unfurling with each project a tangible new fold of black identity to be resonated with, questioned, revisited, sworn by.

The original concept of black genius was coined decades before the Alright rapper’s reign, in a 1999 essay collection composed by Walter Mosely in tandem with others. Much like QuestLove’s interpretation, Mosely’s introduction characterizes it by a reflective duality injected between both sides of two possible lifestyles.

“We understand genius to be that quality which crystallizes the hopes and talents and character of a people,” he says. “This kind of genius is something that we all share. It is a presence where absence once reigned. It is a possibility for people to look into their hearts and see a life worth living.”

Although countless figures in arts and media industries of yesterday met such criterion, mainstream application of the term to prominent creatives – whether explicit or unspoken – only skyrocketed in the remote time period that saw Mosely’s book published. At this point, hip-hop culture found itself in the midst of a historic renaissance. On both coasts of the U.S, independent subcultures that had been churning in ghettos for years birthed poetic prophets that furthered strings of cultural fertility extracting pride from clutches of poverty. When opposite rap infrastructures festered into a cross-country war for supremacy, the once-secondary universe of black music spilled over into the mainstream — a charge led by the likes of Tupac, Biggie, Nas, Diddy, and others, who through both profound lyrical subject matter and (conversely) occasional violent escalations, authentically epitomized the realities of black life on a worldwide scale.

If anyone was the Kendrick of that point in time – the unanimous mantle-carrier of black genius for his era – it was indubitably Tupac Shakur. Much like Lamar, he spent his adolescence in the mean streets of Compton, fostering once-in-a-generation talent soon to be discovered by industry bigs and later introduced to the rest of the world. Once superstar status was attained, these roots served as a foundation for what art followed. Singles like “Dear Mama” and “Changes” stirred black audiences with empathetic bindings absent from what was musically popular at the time, charting highly on media top-100 lists and schoolyard MC rankings alike. To this day, it’s no surprise how intrinsic his connection was: whenever there is an argument about whether the substance of “real” music has passed away (it hasn’t), his name is naturally the first to be brought up.

But the foremost fault in his entire stature as a black genius is a matter of if he asked for the title – and the strict standard that accompanied it – in the first place: which he did not. Black genius is never self-proclaimed; if it is, the term’s usage is more likely than not wielded in vain. Yet, the essence of Black Genius is conceptually that the same people who get to determine its presence are the people for which the art in question is, or was, created. Though the artist him/herself never truly has a say in what label they are adorned with, they carry an unspoken responsibility to live up to the standard insinuated by how their art is construed.

In a 2018 essay by Jayson Greene cited in the New Yorker piece, the futility of black genius is represented by its own internal flaw of who gets to dictate the status quo.

“The larger cultural insanity of genius,” Greene writes, “twists all of us. To believe in genius is to believe in saviours. It is to lie in wait for cult leaders to arise. Elevating geniuses automatically subjugates the rest of us.”

After Tupac set a precedent for black artists to come, there existed a silently prevalent expectation for every artist of color to display some level of black genius. Luckily for him, he was the one who set the bar: much like anyone who presents a group project first in any classroom, the full pressure of adhering to it did not necessarily apply to his case as much as it weighed on those who came after. Yet: even for someone removed from the complete scope of it, the mantle of black genius bred a level of scrutiny that turned minor slip-ups into major slaps in the face of the black community. When Tupac was accused of sexual assault in 1993 by the since-disgraced Ayanna Jackson, it was a case that attracted national coverage. As recounted by Touré, a journalist who covered his trial, every time Shakur stepped foot beyond courtroom doors for recess, media teams flocked aggressively, with boom mics, video cameras, and notepads scrawled with shorthand. On both sides of it, there were issues within communities of color that were dragged into global spotlights alongside the rape case: debates around the credibility of black women; questions surrounding the tendencies of black men; overall skepticism of the abilities of black people to exist within what peace they fought for. And – though Tupac handled the entire ordeal with class – the wounds incurred from it left deep scars on the reputation of black America: wounds from which healing is still happening.

Michael Jackson is one of many infamous snapshots of what immediate effect the sudden standard of black genius had on those who both rose with, and succeeded, the slain California poet. The story is one passed down for generations: Michael Jackson was born with dark skin. He grew up with it, emanating the beauty of black culture through soul music produced alongside the Jackson 5 and looks that graced magazine covers alike. At some point following the release of Thriller, however – when the unspoken mantle of black genius was in full effect – he incurred burns to his face in a freak accident on set for a Pepsi commercial, triggering a quiet newfound obsession with medical altering of bodily imperfections under the knife. After enduring a silent struggle with vitiligo for years, perhaps in tandem with the latter, he donned a pale complexion for the rest of his years: a move many in the black community never forgave him for. Given the secrecy with which the transition was handled, many up to this day theorize that Jackson was simply tired of being black; that he sought to escape the hardships of marginalization in his artistry (“but it was too late!!!” one Instagram caption declares); that he had committed the ultimate atrocity against his own people. But on Jackson’s side, it was merely an escape from something he spent his entire life tormented by. “Okay, but number one, this is the situation. I have a skin disorder that destroys the pigmentation of the skin; it’s something that I cannot help,” he famously said on the Oprah Winfrey show in 1993. Oprah had asked whether he bleached his skin because he didn’t like being black – he spoke nervously in his defense, adamant in favor of his case, yet visibly vulnerable, stuck at the cataract of letting his emotion get the best of him. “But when people make up stories that I don’t want to be who I am, it hurts me.”

Artistic parallels between Tupac and Kendrick Lamar extend to what has come of similar standards: just as the major stain on Tupac’s legacy was his aforementioned rape case, his apparent protégé garnered mass criticism for remaining silent during a summer of riots and protests. Both cases – whether surrounding personal or artistic decisions – were quickly stripped out of the subject’s control.

This is the essence of what makes black genius futile: as high as the highs are for black culture, the lows for both artist and represented demographic barge through intrapersonal boundaries – haste to craft pernicious reputations out of half-truths – subjugate many at the cost of idolizing one. Without verbal or contractual agreement, creatives elevated to such stature are subconsciously held to strict honor codes that, once broken, spill irreversible stains on their legacies. And because of bars set by all who have donned the mantle before, we subconsciously demand all artists of color to exhibit a black genius of their own.

In a June Sammy’s World interview centered around the value of art in protest, the independent curator and journalist Kiara Cristina Ventura said of revolt: “I feel like anything we do as people of color that is geared towards obtaining our freedom in any way, is an act of resistance. I feel like self-care is an act of resistance, taking time off is an act of resistance, relaxing, taking a nap in the middle of the day, you know what I mean?” Going on to speak about conversations she’s had with artists worked with, she shifted sentence structures as if to speak directly to those artists. “Give yourself that space to be experimental. Paint anything, because that’s an act of resistance, too. We don’t have to put our stories of oppression, and struggle, and all of these things at the frontline all the time.”

It is this most basic form of resistance – the resistance (and human right) of simply being – that black genius strips away from its donners. In various instances, when artists have exhibited the natural desire to live amidst periods that saw politics overtake life for many, hordes of criticism forced them back into the standard of black genius in invisible dominion.

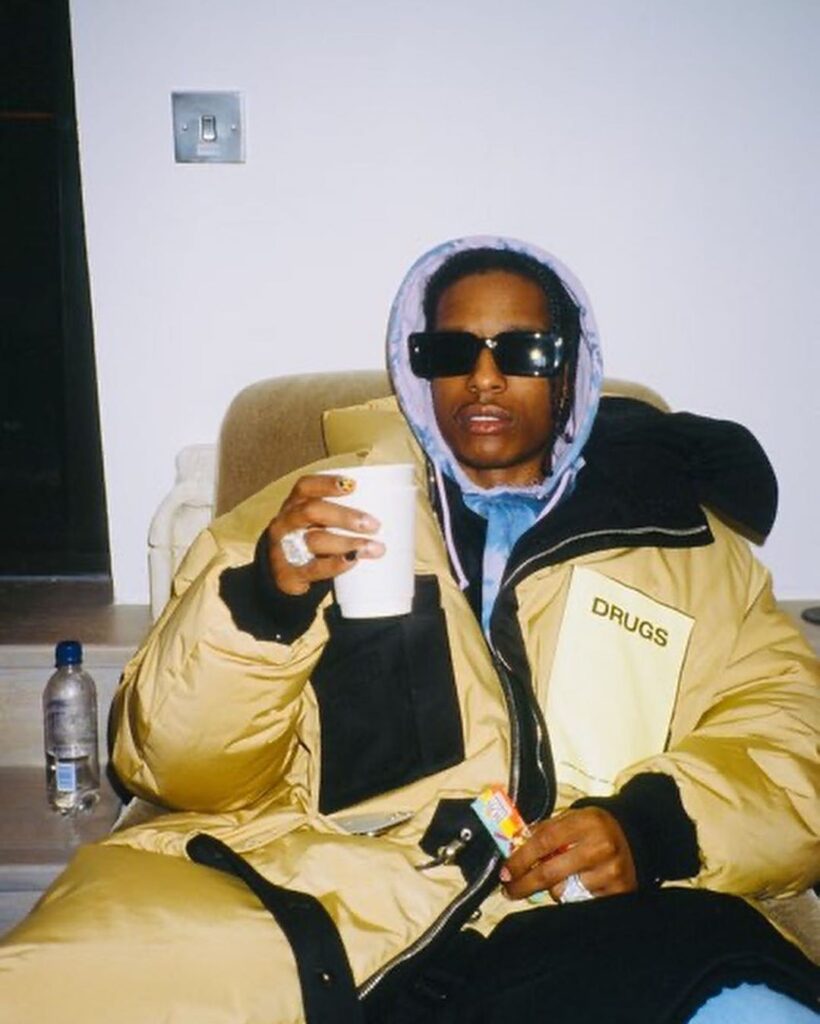

A$AP Rocky’s case sits among a lengthy list modern-day examples. In 2015, he was interviewed by Time Out New York; and, just like what went down with Skepta overseas, he received a talking point he preferred not to address: An argument did arise, though, at Oxford University, when you said you didn’t want to get political in your music, the interviewer mused, referring to a public conversation Rocky led at the institution years ago.

“I think speaking on a subject is fine but I don’t feel like I need to make songs off of it,” he replied, defending his stance. “If I felt like doing it, I would. [That student’s] whole question was, “Why haven’t you [gotten political]?” I’m like, Bitch, ’cause I don’t feel like it. Kendrick is doing that already. J. Cole is doing it already. Let them deal with that shit. I wanna talk about the fucked-up shit in my life. Not that fucked-up shit I see on TV. Because I’m not there. How am I gonna talk about something I’m not helping? It’s fucked up. It’s a touchy subject.”

He then went on to add a point that was not forgotten by the black community: “I can’t relate to no fuckin’ Ferguson. I live in fuckin’ Soho and Beverly Hills. I can’t relate.”

Years later, when he made worldwide headlines behind bars in Sweden following a violent confrontation with locals, two hashtags trended on Twitter: #FREEASAP and #ICANTRELATE. In theory, the latter response is justified: his words were harsh and vile, biting the hand of a demographic that supported his rise to prominence preceding days when everyone knew his name. Yet, on the other end of it, one must think beyond the Harlemite’s ill-advised phrasing: haven’t we all at some point wanted to disassociate? In times of civil unrest, black creatives are often those leading the charge to voice protest and pain – hosting lengthy heartfelt livestreams, fighting through paparazzi within public demonstrations, enduring ruthless criticism, both televised and online, from figures on the other end of the political spectrum. As a member of the race that has had to carry this burden on its back for the entire lifespan of this country – is it so wrong to seek individual comfort in it all?

In Skepta’s case, he is a product of the ultra-prosperous Adenuga family, an artistic monarchy hailing from Nigeria and the UK. Members of his bloodline include mother Ify, the Endless Fortune author, brother Jamie, the acclaimed grime MC finding his name on global charts up to present day as JME, and sister Julie, the former lead DJ for Apple’s 24/7 radio station now taking her talents to the airwaves.

Given his occupation, it’s a shock that in place of the brash, boastful, public persona one would expect him to exhibit beyond the studio, he routinely keeps to himself – and in the silence, one is forced to recognize in full the rich heritage of talent, wealth, and glory that permits him to do so. But when the sole lens through which he, along with hundreds of other black artists, is examined is one transfixed to the nearest straying from black genius: the prosperity that makes Skepta worth talking about in the first place becomes easy to miss.

2 replies on “Skepta, A$AP Rocky, and the Futility of Black Genius”

queen of vibes approved. Great piece Samuel KEEP IT UP I LOVE THIS

This one my favorite