Shame on ODB – and Shame on You, Too

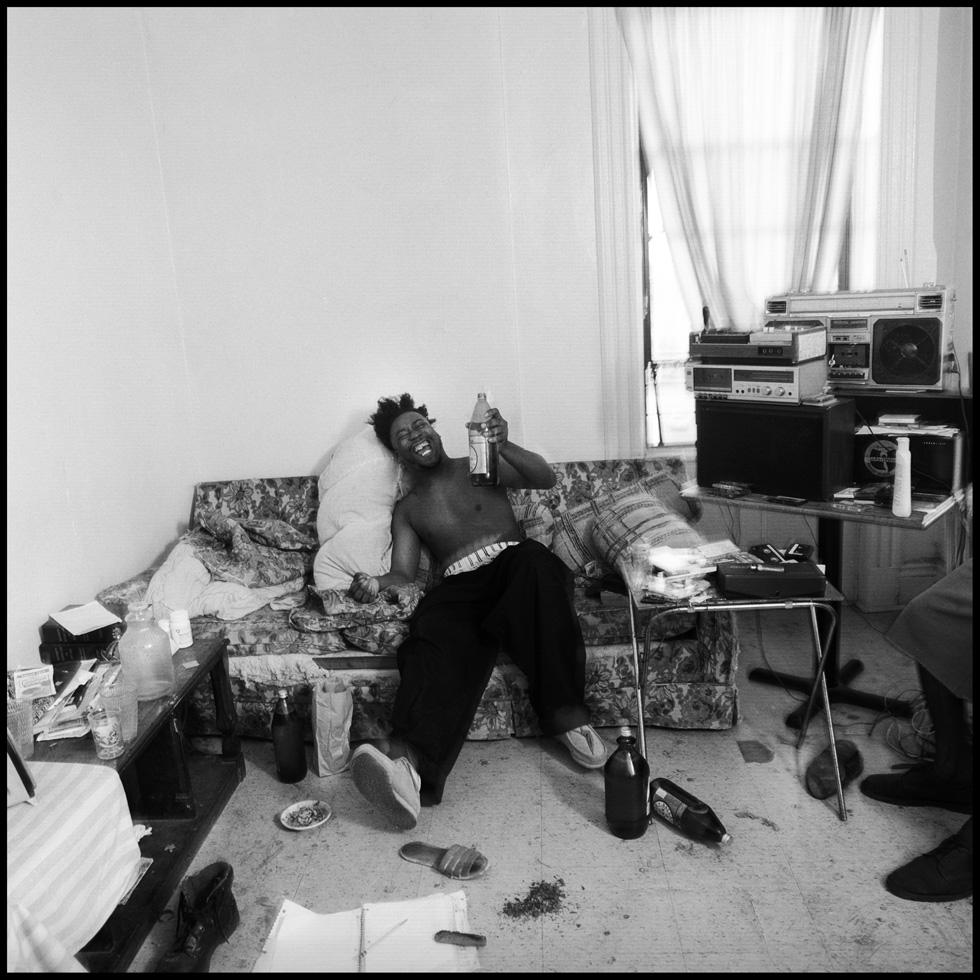

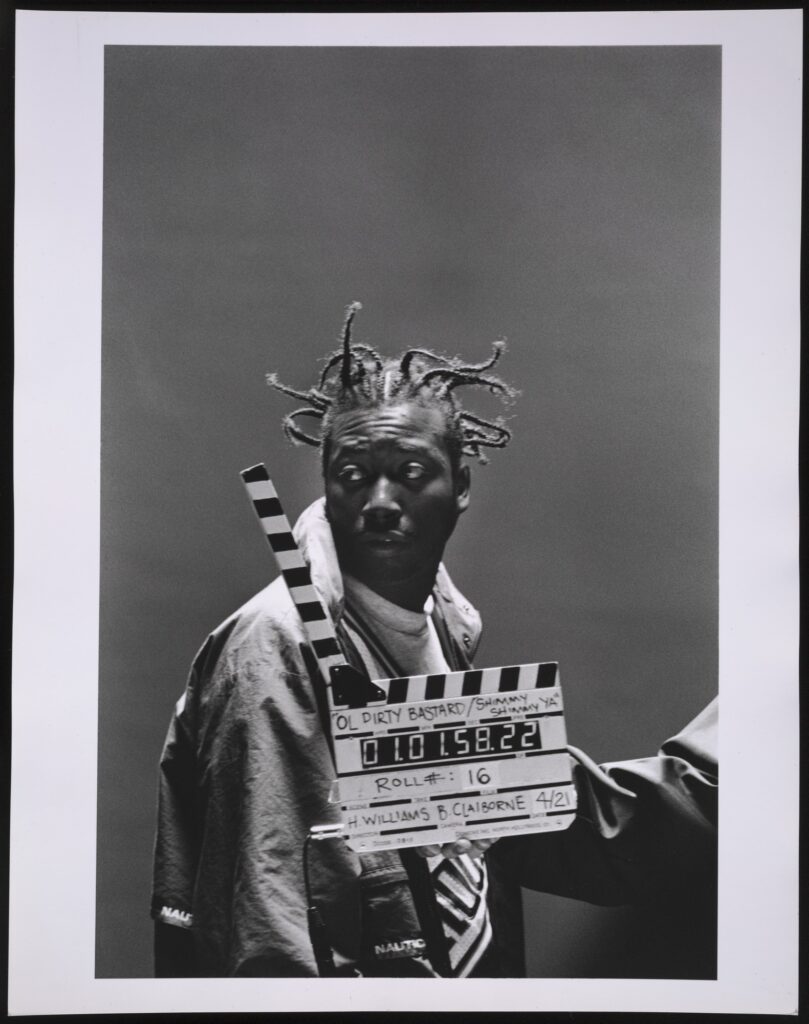

Ol’ Dirty Bastard spent his life confronting a flawed system with the beast it created. (Photo: Danny Clinch)

SAMUEL HYLAND

For a vast majority of those in hip-hop circles, the first trace of Russell Jones’ mythical Ol’ Dirty Bastard persona materialized in the opening seconds of Wu-Tang Clan’s landmark debut LP Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). Over a shuffling backbeat pulled straight from the school of boom-bap rhythms and record scratches long significant of East Coast hip-hop’s early reign, he sneered grim warnings into the ears of both his local rivals and America writ large: “Shame on a nigga who try to run game on a nigga / Wu buck wild with the trigger / Shame on a nigga who try to run game on a nigga / Wu buck… I’ll fuck your ass up!” Across the tumultuous decades that went on to define his career, this shame on you infliction would prove to be a persistent motif. In November of 2000, as the Wu-Tang Clan gathered for a release party in New York City’s Hammerstein Ballroom, Ol’ Dirty Bastard—who had, upon escaping from a Los Angeles rehab facility on foot, been living off the grid for a month—emerged onstage to the jubilant surprise of several hundred fans. “I can’t stay on the stage too long tonight – the cops is after me,” he told the audience, before launching into a performance of “Shame on a Nigga.” In his legendary, hectic solo single “Brooklyn Zoo,” he doubled down on the implication of shame, dedicating the song’s denouement to bone-chilling repetitions of this very conviction. “Shame on you when you step through to The Ol’ Dirty Bastard,” he chanted, oscillating between sweaty televangelist and caricaturing stand-up comic. “BrookLYNNN… Zoo.” In 2006, two years after he would collapse in Wu-Tang’s New York City recording studio and die of an accidental drug overdose, his 15 year-old son recited the same drawl, warning included, at a Clan concert as an homage.

“He was lurching around with these huge wide steps. You could tell he was a star. You couldn’t take your eyes off him. He had charisma. And I said to myself, ‘That’s Russell Jones. That’s the O.D.B.’”

Ol’ Dirty Bastard was an extremist when it came to introducing himself. In the opening seconds of his debut album Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version, he donned the persona of a show promoter to handle prefacing duties: “He’s somethin’ insane, he’s the greatest performer ever since, uh… What’s the guy’s name? Ah, ah, ah… James Brown,” he jested. It’s blasphemy-bait in the most blatant sense, a direct invitation for the generation who witnessed Brown’s intense work ethic firsthand to throw off their headphones and damn Ol’ Dirty Bastard to hell. But the differentiating factor, in Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s case, was that hell was already his home. He wasn’t nearly as intent on striving for a social asymptote as he was on lathering himself in what hellfire he had already been sheathed by; where for many, the “Brooklyn Zoo” he often brought up in his raps was something to be reviled and escaped, he embraced his position as a spectacle, instead opting to give onlookers far beyond anything they could have possibly come to see.

It was this fiery quality that made him the face of New York’s vicious hip-hop underbelly. And it wasn’t a mask—he had the scars to prove it. At some point in “Shame on a Nigga,” the track that introduced both himself and the Wu-Tang Clan to ears worldwide, he posed a rhetorical question to an unnamed rival: “Do you wanna get your teeth knocked the fuck out?” This was not a case of the contemporary all-talk-no-action rap infrastructure oldheads lament against at family barbecues, where music videos for songs about grimy streets are made in ritzy AirBnBs, and figures like Flyysoulja and Kodiyakredd get to don thuggish, hyper-Floridian mystiques while living lavish at heart. When you do a Google Images search for Ol’ Dirty Bastard, some of the first photos that show up feature him bearing a mischievous, full-mouthed Cheshire grin, wherein the few teeth that are still there seem to dangle from his gums, encased in gold grills that appear to be more of a casket for each tooth than an accessory. Ol’ Dirty Bastard had far more than a few teeth missing. In 2012, Rich Jones of the hacker-oriented blog Gun.Io filed a Freedom of Information Act request to the FBI for “all documents mentioning Russell Tyrone Jones, aka Ol’ Dirty Bastard, aka ODB, member of the ‘Wu-Tang Clan’ hip hop collective.” The entire report was 95 pages in length.

“JONES was awaken from his sleep by a man who was pointing a .357 or .45 caliber grey gun in his face,” one section of the file stated, detailing an armed home invasion in which ODB was the victim. “JONES was unaware of what was happening and reacted by jumping up from the bed. The UNKNOWN MALE (UNM1) and JONES wrestled until the UNM1 shot JONES in the arm and back. At first JONES was not aware that he was shot.” The section went on to detail the theft of jewelry from his body, the fleeing of his attackers, and his bullet-riddled drive to a local hospital for his own survival. Another note, dated January 15, 1999, read that: “Russell ‘Ol’ Dirty Bastard’ Jones NYSID #5627626P while in company of his [redacted] following a car stop in confines of 77 Pct. Brooklyn, N.Y. was involved in a shoot out with N.Y.P.D police officers. Jones was charged with Attempted Murder. A Brooklyn Grand Jury failed to indite him.”

The fact that these two snapshots comprise only a miniscule percentage of the FBI’s complete documentation on him—that is, the amount of his lifelong tumult that actually went on the record—shines a light on how thin of a tightrope his career was ultimately staked on. By all accounts of the time period, environment, and infrastructure from which he emerged, Russell Jones was not supposed to survive long enough to be anything beyond just Russell Jones. An outcome more in line with the grim realities faced by those like him was, rather, congruent with an adage recited by fist-shaking teachers and grandmothers all across New York’s most violent neighborhoods: “either dead, or in jail.” The sound of his voice on wax, in and of itself, is a miracle. Before rags to riches, the hurdle that defines a career (or lack thereof) is streets to studio. Many are swallowed by the first frontier before they can make it to the next. Despite his electric energy, Russell Jones was ostensibly slated to be a passenger on the same fatal conveyor belt—his persona was one abnormally emblematic of a bursting, militant hip-hop revolution soon to command the nation; but still, any revolution could only have worked if there was some form of manifesto to be excavated from the streets in the first place. And Jones wasn’t just bedeviled by the streets; he was the epitome of their clutches. In more ways than one, getting him to graduate from the streets to the studio was, if feasible at all, perpetually a now-or-never affair. “I knew I had to get it to the finish line because there are times in life when you know you only have that moment in time, and you gotta get there,” Elektra Records A&R Dante Ross said of The Dirty Version’s recording process. “I had to get there, ’cause I strongly suspected that would not happen again.”

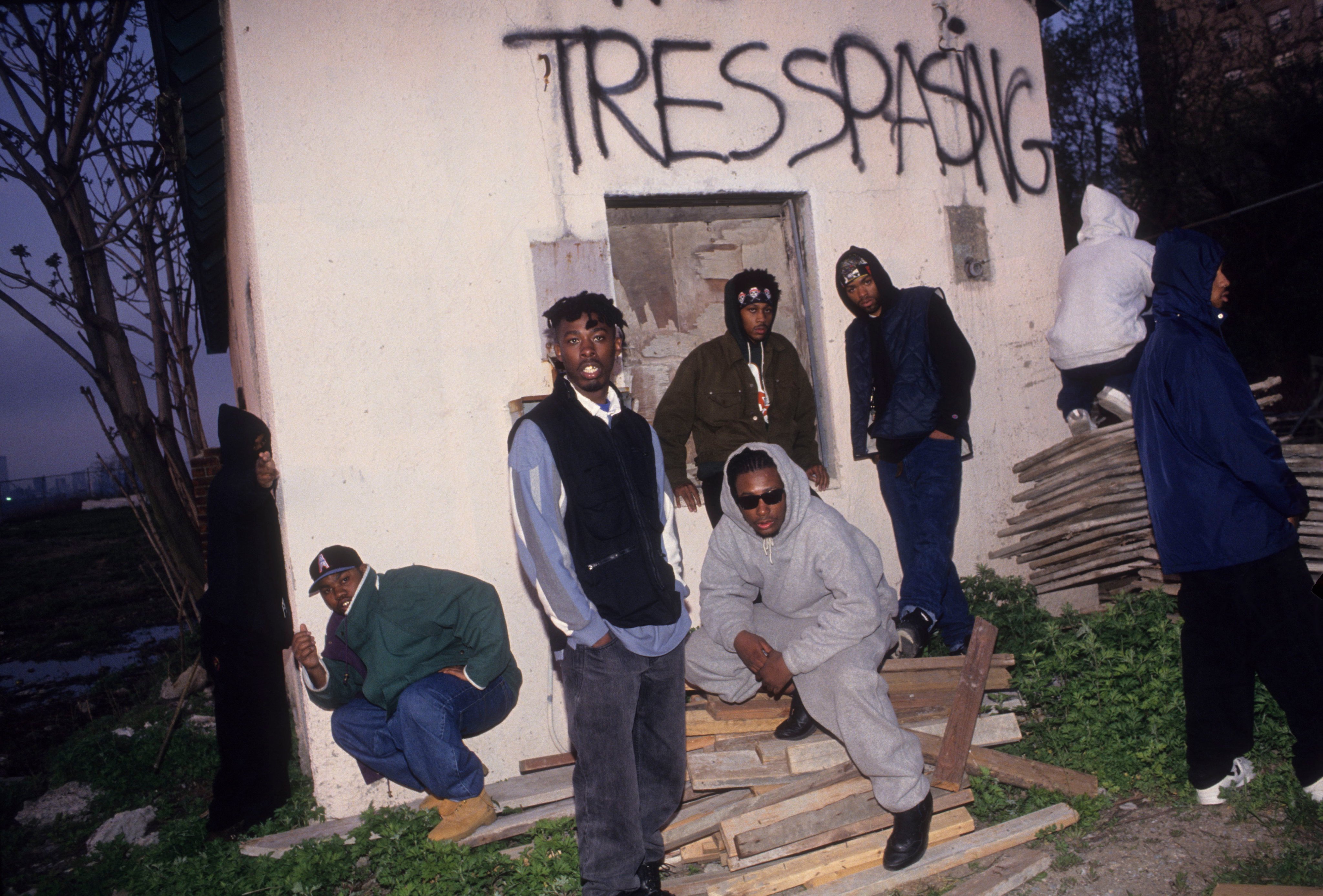

“They weren’t only graduating from the streets to the studio. They were letting the two bleed into one another.”

Ross’ assessment of such energy as once in a lifetime is applicable to, more widely, the Wu-Tang Clan from which Ol’ Dirty Bastard initially emerged. One of the first samples that appears on The Dirty Version is a direct quotation from the 1978 film The 36th Chamber of Shaolin. “We have only thirty-five chambers… There is no thirty-six,” an overtly cartoonish voice says in the track’s closing seconds. Much like protagonist San Te in the movie, the joint goal of Wu-Tang Clan collective was to (1) seek to discover an untouched frontier, and (2) if it turned out to actually not exist, be the ones to invent it. The group’s primitive beginnings came in the form of Jones, alongside cousins Robert Diggs and Gary Grice, comprising a three-man faction dubbed “Force of the Imperial Master.” Though this specific endeavor never did earn the group a record deal, it made waves across New York City’s burgeoning rap scene, building stock for potential signage to be cashed in on by its individual founders. Each member recorded under an alias—Grice as “the Genius,” Diggs as “The Scientist,” and Jones as “The Specialist.” After all three rappers except Jones recorded solo albums under brand new record deals, Grice and Diggs were quickly dropped by their labels. They renamed themselves again: this time, respectively, to GZA, RZA, and Ol’ Dirty Bastard.

Ol’ Dirty Bastard adopted his moniker from a character in the 1979 film Ol’ Dirty Kung Fu (the Wu-Tang Clan were very preoccupied with Eastern philosophy and action movies) who, distinguished by his overt drunkenness and obscenity, was given the name “the Drunken Master.” As far as Jones’ own usage, the moniker is doubled down upon in “Raw Hide,” off his debut album: “See this ain’t somethin’ new that’s just gonna come out of nowhere,” he screeches, in an intonation that is admittedly unsettling. “No! This is somethin’ old! And dirtayyy!” Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s grotesque fury wasn’t cultivated strictly for in-studio use, like Bruce Banner suddenly bulking up whenever it was convenient and letting it all go when the moment passed. This fury was years in the making. And when it spilled out, it was a damning indictment of everything that made Russell Jones the Old Dirty Bastard he was.

When Wu-Tang Clan would—with the additions of MCs Inspectah Deck, 4th Disciple, Chostface Killah, Masta Killa, Method Man, Raekwon, and U-God—go on to record Enter the Wu-Tang, the group was heavily contingent on claiming its once-in-a-lifetime essence in full form. They operated in layers upon layers of codes and self-created slang; for instance, their Staten Island hometown was affectionately referred to as “Shaolin Land,” and money was “C.R.E.A.M.” Their tactical approach garnered them a cult following, one that would only expand as Wu-Tang’s music and mythology each continued to unfurl. At the very same time that they were surging by way of nerdy Kung-Fu raps and aesthetics, they were also, according to Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s aforementioned FBI file, “heavily involved in the sale of drugs, illegal guns, weapons possession, murder, carjackings, and other types of violent crimes.” Their earworm warble “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthing Ta F’ Wit” was more than just violent lyricism. They weren’t only graduating from the streets to the studio. They were letting the two bleed into one another.

“All you were left with was the stench of fresh urine on your prized morals, and the explanation that he was ‘just out of his mind that day.'”

Wu-Tang Clan’s deal with Loud/RCA Records was, for its era, revolutionary in that it allowed each member to record solo albums with other labels while still being under contract with the group. This clause was specifically devised with the intent of long-term usage, a de-facto launchpad for supremacy across hip-hop scenes. After Enter the Wu-Tang, the group sought to forge its next step by way of a smattering of solo records from each of its members. Ol’ Dirty Bastard was meant to be the first of the collective to release an LP. Except he couldn’t finish his album—because he was too busy spending his advance check on a decrepit car, and using the broken-down vehicle to go on expansive, aimless drives for days at a time. When he would return to real life after his lengthy forays, he was often drunk and unpredictable. One especially lewd incident came when, while he was technically still supposed to be working on his tape, LL Cool J was interested in featuring him on a track. “I get the call from Chris Lighty, who’s managing LL Cool J at the time, and [he] says, ‘I want to put your man Ol’ Dirty on a song with LL. LL really feels him,” Ross recounted in a YouTube video. “So I get Dirty there. He shows up with a guy named Crazy Sam. We start trying to get him to rap on the song — he’s not doing it. He’s listening to the beat. He’s wasting time. Finally Chris is like, ‘Yo, my man, what are we doing here?’” In the hectic moments that followed, Ol’ Dirty Bastard would go on to suddenly curse LL Cool J’s name, express his disgusted disregard for the rapper through a series of expletive-laden declarations, and, finally, seek to demonstrate these feelings in physical form. He ripped LL Cool J’s platinum plaque off of the wall. He pulled his penis out of his pants.

“I walk upstairs, and Dirty is there,” Ross said. “Real talk, Dirty had peed on the LL record. That was the real deal. Ol’ Dirty Bastard and LL’s great collaboration never came off, cause Dirty was out of his mind that day.”

In the miracle that is Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version, this exact sense of unbridled, maniacal terror shines on throughout; like a burning pile of rotting garbage in an inner-city New York backstreet, its overbearing grotesque surpasses the disgusting and channels the sublime. When, for my 14th birthday, a middle-school me was gifted with a trip to the local mall’s FYE branch, my mom shot me a strict glare upon my fixation on Nirvana’s Nevermind. “Don’t get anything weird,” she scolded me. If the album I was looking at happened to be The Dirty Version, chances are that I would not be alive to type this sentence.

Ol’ Dirty Bastard is widely regarded as the originator of the “weirdo rapper” archetype thrown onto modern-day acts like JPEGMAFIA, Danny Brown, and Young Thug. But the distinguishing factor in such a pantheon is that Ol’ Dirty Bastard was beyond both mere weirdness and salvation. The crux of culturally-embraced weirdness, as wielded by Brown, Thug, and Peggy, is that it is something palatable enough to be aestheticized and commodified. In ODB’s case, the specific brand of aberration he exuded felt, rather, like getting your platinum plaque pissed on. Without remorse. He didn’t care about how you felt, what you had to say about it, or the prospect of getting caught (hence the 95-page FBI file). All you were left with was the stench of fresh urine on your prized morals, and the explanation that he was “just out of his mind that day.”

Near the end of “Drunk Game (Sweet Sugar Pie),” for instance, there is a portion where Ol’ Dirty Bastard devotes the better part of an entire verse to primitive, lustful growls crooned over a somber church organ. He goes from sounding like a perverted old man engaging in his first taste of sexual debauchery for decades, to a tortured dog, panting for breath and choking on his own lecherous saliva. It’s one of several jarring moments on the record where ODB seems to throw all care for his image out of the window (if it was ever there in the first place), and the pure, unadulterated monstrousness that defined his aura seems to stick its tongue through your headphones and lick your ear’s innermost parts.

“Ol’ Dirty Bastard was willingly stepping into the hellfire. But whether he intended to or not, he may have been dragging an entire race of people with him.”

“Don’t U Know,” too, sees Ol’ Dirty Bastard lug his delirious intonation through lines and lines of troublesome sexual imagery; there is a strikingly menacing melody in his trembling vocal chords, and he sounds a lot like the perverted, cigarette smoke-bathed cab driver who keeps asking you whether your mom has divorced your dad yet. Strangely enough, through all the unwelcome sonic urination that is forced into the victimized ear canal—much like the ever-so-thin tightrope he spent his career at the mercy of—there is a point where you realize that it can’t just be a matter of luck that he’s still going. “Hearing ODB spit rhymes was like watching a delirious man wander into a busy intersection and, through sheer luck or divine intervention, avoid getting hit by oncoming traffic,” New Yorker editor Sheldon Pearce said in a Pitchfork review of the album. (It received a rating of 9.3 out of 10). “With each daring escape, each narrow staving of catastrophe, it becomes harder and harder to dismiss his nimble maneuvers as chance.”

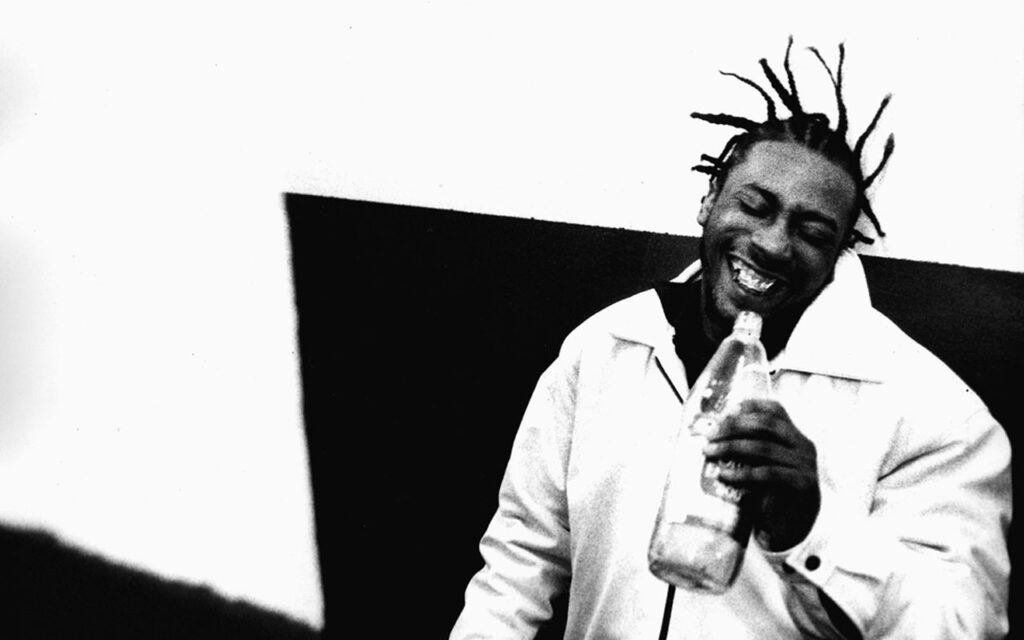

In one 2005 New Yorker essay, following Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s death two months prior, culture editor Michael Adder chronicled a long-winding series of wrong number phone calls directed to a man named Russell Jones who, despite living in Brooklyn, was not exactly the grotesque Wu-Tang caricature people were looking for. This Russell Jones, rather, was a forty year-old art director who described himself as “white” and “meek.” After the relentless phone calls prompted his cousin to inform him of ODB’s real identity (Jones didn’t know who the rapper was, and was thus understandably very confused), he gave up being annoyed, and grew enthralled with Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s mystique. Curiously, practically every caller seemed convinced that, despite his vehement denials of being the person they were looking to contact, the two were somehow related. Many asked him to extend messages to the rapper when they next convened. Jones never thought he would meet Ol’ Dirty Bastard in real life—and much more to the point, he didn’t have the slightest idea what he looked like. But when he did happen to coincidentally run into him on the street one day, after an entire decade spent answering these erroneous phone calls, he somehow knew exactly who it was. “It was an incredible moment,” Jones said. “There was this guy with mini-dreads who had his shirt off. He was wearing cutoff overalls and Timberland boots without socks. He was lurching around with these huge wide steps. You could tell he was a star. You couldn’t take your eyes off him. He had charisma. And I said to myself, ‘That’s Russell Jones. That’s the O.D.B.’”

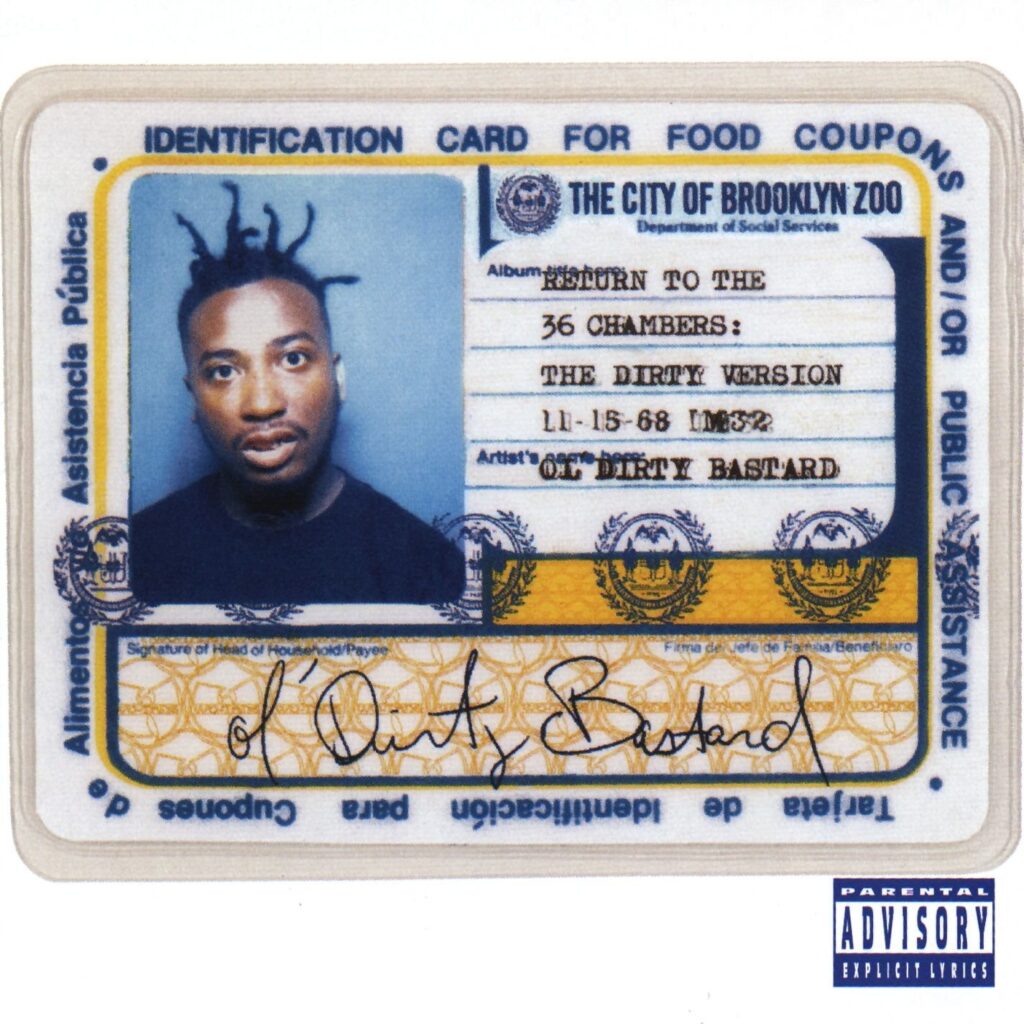

Stories like this one make Ol’ Dirty Bastard sound like a mythic fairy tale hero in spite of his well-documented savagery, and in many ways he was. With what money he earned from taking the streets to the studio, he often funneled his affluence right back down the pyramid, handing it out to children on Brooklyn’s streets. When he wasn’t doing that with the cash, he was using it to financially support his relatives, whether purchasing cars for his mother or helping his father to buy a house. The image of Ol’ Dirty Bastard seared into the minds of most hip-hop fans is the government-issued food stamp card that graces The Dirty Version’s cover. With his blank, aloof glare, he seems to throw your scorn back at you just as frivolously as the dollar bills.

☯️ ☯️ ☯️

At the 1998 Grammy Awards, sometime after Wu-Tang Clan’s second LP Wu-Tang Forever lost “Best Rap Album” to Puff Daddy’s No Way Out, Shawn Colvin mounted the stage to deliver her acceptance speech for “Song of the Year.” Before she could utter a word into the microphone, out of nowhere boomed the voice of Ol’ Dirty Bastard, demanding in his psychotic lisp that the crowd be silent and that the music be shut off. The television camera panned across the platform. Bespectacled, Ol’ Dirty Bastard was standing at stage center, an excessively large brown suit seeming to swallow his body whole. His iconic crazed mini-dreads were braided into neat cornrows.

“I went and bought an outfit today that costed a lot of money,” he started. “You know what I mean? ‘Cause I figured that Wu-Tang was gonna win.” For a generation that saw Kanye West do the exact same thing to Taylor Swift in 2009, one would assume that by this point—the equivalent of West exclaiming “Imma let you finish, but Beyoncé had one of the best videos of all time!”—the audience would erupt in either agreement, surprise, or both. On this evening in particular, when Ol’ Dirty Bastard made his grievances known, the crowd was dead silent. It looked a lot like one of the humdrum public forum events parodied in Parks and Recreation episodes, where passionate government officials deliver emotional outpourings to rooms full of citizens bored out of their minds. And for the entirety of ODB’s spiel, all 6,000 or so A-list audience members stayed just like that—silent, like an overbearingly passionate politician was making them late to pick their kids up from school.

“Yo. I’m glad to get the food stamps. Why wouldn’t you want to get free money!?“

“I don’t know how y’all see it, but when it comes to the children, Wu-Tang is for the children—we teach the children,” he continued, as an official-looking older gentleman rushed onstage to grab hold of him. “Puffy is good, but Wu-Tang is the best. Okay? I want y’all to know that. This is ODB and I love you all. Peace!”

The incident is one micro-level representation of a quality Jones exhibited even beyond artistry: he was all about getting what he felt was rightfully his, and he was unrelentingly vocal about it when it wasn’t granted to him. Ol’ Dirty Bastard wasted little time making it known that his most despised swindler was the American government. At some point during an MTV camera crew visit in 1995, he declared boldly into a microphone, “you owe me forty acres and a mule, anyway.” Even more telling than this statement were the overarching circumstances for MTV’s mini-doc: he was picking up food stamps… in a stretch limousine. It’s a brash, perhaps even infuriating, image of exploitation in its most spiteful form—in a neighborhood overrun with poverty, destitute families braving crazy lines for governmental access to their next meal, a well-known rapper pulls up in a sportsy limo and essentially takes food out of someone else’s mouth. It’s a shame on Ol’ Dirty Bastard. But perhaps even more so, there is an even greater shame intentionally illuminated by his act. The government existed in such a way that rap’s most riveting superstar could be fed from the same spoon as the hungry. Yes, shame on Ol’ Dirty Bastard for exploiting the system. But, ODB seemed to be saying, shame on the system for being exploitable, too. “I just wanted to show people how to be real with it,” he told an MTV cameraman about The Dirty Version’s cover. “I’m on welfare right now. For real. Once you put that card in there, we got food stamps. Yo. I’m glad to get the food stamps. Why wouldn’t you want to get free money!?”

When all is said and done, Ol’ Dirty Bastard was only able to pull such a stunt because he had not filed his taxes for the previous year, thus making him eligible for welfare despite receiving a $45,000 cash advance for the recording of his debut LP. After viewing the MTV clip, Jones’ caseworker reviewed his files, and his eligibility for welfare was immediately revoked. Such abuses of the program, this one being a nationally popular example, led to the ultimate termination of the welfare initiative across the United States. In many ways, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, in satisfying his own malicious character, had ruined it for everyone. And it went beyond just benefit checks. In the aforementioned Pitchfork review, Pearce cited a comedy sketch in which Chris Rock used ODB as an example of the politicized distinction between “black” and “nigger.” “To Rock, as to many, ODB was a depiction of a kind of blackness that was obscene: ignorant, dependant, deviant, unkempt, unruly, and, worst of all, uncontrollable,” Pearce wrote. “He was a character that has persisted in the cultural lexicon decades later: the crazy black homeless man as personified in novels like Same Kind of Different as Me or the shabby, mentally ill virtuoso of films like The Soloist.”

For as much as Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s carefree character contributed to African-American culture on an inward front, the question exists of whether his output was more helpful or hurtful in the larger sociopolitical canon. One of the most common grievances wielded against Russell Jones is the same exact thing that made him remarkable in the first place: he was a caricature, a violently exaggerated embodiment of what vicious savagery the United States of America was capable of manufacturing. This was both a blessing and a curse. For one, one of (if not the most) effective means for calling out a flawed system is to confront it with the beast it created—and he was perhaps one of the few willing to do it, if at all, in such a public way. At the same time, the revulsion with which such a radical image was addressed was bound to be cast onto anything remotely in its social vicinity. Ol’ Dirty Bastard was willingly stepping into the hellfire. But whether he intended to or not, he may have been dragging an entire race of people with him.

“-The cover of ODB’s debut album Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version prominently featured a picture of his welfare card,” Shaun Ossei-Owusu wrote in a Huffington Post essay reflecting on Jones’ cultural footprint. “The portrait — which is now a mural in a gentrifying section of Brooklyn that Dirt probably would not recognize were he alive — alludes to the publicly defiant ‘bad nigger’ tradition that stretches back to black boxer Jack Johnson and exists today in social media-induced displays of black criminal behavior.”

“Everywhere he went, people fell in love with him immediately.”

What made his case different, yet, was simply that Ol’ Dirty Bastard didn’t care. Apart from the “Drunken Master” character from Ol’ Dirty Kung Fu, ODB also explained that his name stemmed from there being “no father to [his] style.” Both in the realms of music and culture at-large, this was beyond doubt. Sonically speaking, there are few pre-ODB rappers (and probably post-ODB rappers, too)—if any at all—that would introduce their solo acts to the world by way of predatory lyricism, ultra-deranged imagery, and entire verses of troubling, animalistic moaning. On the cultural front, there was never, nor will there likely ever be again, someone so willing to dehumanize themselves to such an extent purely out of spite. A year ago, I visited a studio in which one sculpture, hung up on a wall, featured just a (humanely-sourced) tortoise shell and an assemblage of remote-control car antennas protruding outward from each of its hexagonal scutes. Ol’ Dirty Bastard operated a great deal like this tortoise sculpture: he invited scrutiny, and threw fat chunks of it right back in the face of the scrutinizer.

Even for the extent at which he was a spectacle, the Russell Jones that lay beneath Ol’ Dirty Bastard had a heart that was often concealed for the cameras. One telling incident, quite similar to fables in which he handed out money to Brooklyn’s children, came when he witnessed a car accident from his New York recording studio. After organizing about twelve bystanders with a friend, he and the group lifted a 1996 Ford Mustang up from the ground and rescued an injured 4 year-old girl from the debris. Jones used a fake name to conduct regular hospital visits. These lasted until, after consistently visiting without ever identifying himself to her family (for obvious reasons), they eventually wound up recognizing him and alerting the media. One is forced to wonder what was behind this decision. There is much reason to believe that they thought their daughter to be in danger; just the same, they could have been starstruck and hopeful to get the story out. Either way, Russell Jones was not what American culture needed to see. American culture needed to see Ol’ Dirty Bastard. And when the cameras came, and the headlines were all-but written, the human being behind the drunken master was nowhere to be found.

The year of his death, Ol’ Dirty Bastard was enlisted by Mariah Carey—then an up-and-coming R&B singer—to provide a guest verse for the Puff Daddy-produced “Bad Boy” remix of her song “Fantasy.” Columbia Records had granted Carey vast autonomy in curating the new version. But when they heard that ODB was to be featured, they pushed back, fearing that it would derail her career. Although Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s verse eventually wound up being included, there exists a version of the song (the “Bad Boy Fantasy Remix”) in which his contribution is completely cut out.

Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s final days were mostly spent in hotel rooms. He began to miss Wu-Tang Clan concerts more and more frequently. At one point in the summer of 2004, RZA tried to bribe him with an extra five thousand dollars to get him to leave his accommodation and perform alongside the group at that year’s Hot97 Summer Jam. The following November, after he missed another concert, Method Man called him out in front of the audience. “There’s no one bigger than the Clan,” he said. “When you see Ol’ Dirty Bastard, tell him that.” Exactly one day afterward, at about 4:30 PM outside of Wu-Tang’s studio in New York, a 36 year-old Ol’ Dirty Bastard collapsed. He was dead of congestive heart failure before pandemics arrived.

To his very death, ODB epitomized the lightning-in-a-bottle construct that made both his career and that of the Wu-Tang Clan volatile; it was a brand that burned out rather than fade away, and when the substance was gone, everything stopped just as suddenly as it began.

At Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s funeral, RZA, his cousin, said that he was a “unique soul in the family,” and that “everywhere he went, people fell in love with him immediately.” He also admitted that as Jones’ struggles began to loom more and more, he told him: “I’m dying.”

With certain ill-fated musical talents, it has often been reported by surrounding figures that there was an eerie, unspoken-yet-prevalent sense that they would die young. In a recent personal essay published in the New Yorker, writer Michael Azerrad recalled feeling the sensation in his first visit with Kurt Cobain. “The other thing I realized is uncomfortable to say: I sensed that he was one of those rock musicians who dies young,” he wrote. “I’d never met someone like that before or even known many people who had died at all. I just sensed it. It turns out that a lot of other people around him did, too: his bandmate Dave Grohl sensed it, and so did Kurt’s wife, Courtney Love. Even Kurt’s own mother acknowledged it.”

With the death of any well-known artist usually comes a sort of collective surprise, followed by a newly eulogilical lens through which the music is now consumed. (In this day and age, this step is followed by the posthumous releasing of various mediocre projects without the consent of the deceased). But in cases like those of Ol’ Dirty Bastard and Kurt Cobain, much like Rufus Scott in James Baldwin’s Another Country or Giovanni in Giovanni’s Room, it is easy in the grimmest sense to tell that the tightrope can’t sustain a certain weight forever: at a certain amount of miles per hour, the only possible result is a wreck. The question then becomes one of prevention. Is it possible at all, when an artist is living at this dangerous of a pace, to stop them? And if the answer is yes, is it then possible to keep them buckled in forever?

Very much in line with the “dead or in jail” threat of fist-shaking grandmothers, there is a distinct determinism in certain musical scenes where, once one is in too deep, the only ends possible are bad ones. In this way, the music industry acts a lot like the drug business. If the sin of the former is commodification, the surface exists in realms where the art is generally limited to the recording process; it is a haven where streets and studio are kept independent of one another, and not made to converge. The musical parallel to the drug world’s vicious underworld is where the opposite takes precedence—the streets become the studio, and the studio becomes the streets. Scenes in which the music is less a first-person statement and more a documentation of a fast-paced culture offer compelling entry-points. It is fairly easy, and exciting, to identify with a certain wave and seek to emulate it yourself. Such mirrors comprise the outer linings of cultural nuclei; they are the Soungarden, Alice in Chains, and Pearl Jam to Nirvana’s grunge revolution; the Diplomats, A$AP Mob and G-Unit to Wu-Tang Clan’s volatile posse-cut approach. But the storm rages the hardest in the middle. And when you are the originator, from day one, you are inherently at the point of no return.

Within the Wu-Tang Clan’s radical chaos, Ol’ Dirty Bastard was the most far-gone. Much like he unintentionally may have done with the Black community, he became an unofficial mascot of sorts for the group, a frontman without the title. If the Wu-Tang Clan were, with their collective role as originators, already headed for the brunt of the impact, Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s fate was, by some intangible metric, already sealed by the time he picked up a microphone. And once the train was on the rails, whatever tried to stop it would be on the same trip to the end—or, in this case, a section in ODB’s 95-page FBI file.

Over a decade later, now that much of the debris has cleared, another common frontier in the aftermath of musician deaths is being reached: questions are beginning to arise about a second Ol’ Dirty Bastard. Several rappers have either asserted themselves, or been nominated, as potential fillers of these shoes. For one, there’s the New York rapper RXK Nephew, who went viral last year for lyrics that followed more of a violent stream of consciousness than a conventionally comprehensible rhyme scheme. (Lines from “Early Age Death” include: “I’ma change my namе to ‘Slap A Bitch’ / I’ma change my name to ‘I got coke, crack and shit’ / I’ma changе my name to ‘New Ol’ Dirty Bastard’ / They said I’m a young Ol’ Dirty Bastard”). Then, of course, there is the aforementioned class of “weirdo rappers” represented by the likes of Young Thug, JPEGMAFIA, and Danny Brown, who seem to push the genre forward while at the same time existing entirely in juxtaposition to it.

“Love it. You know what I’m saying? ‘Cause you ain’t gonna see no talent like this again in your life.”

These are all very strange characters. But, by definition, they cannot be bastards. Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s style, as he proudly declared, had “no father.” Every weirdo after ODB is, whether directly or indirectly, a brainchild of the man with no shirt, cutoff overalls, Timberland boots without socks and mini-dreads; the mythic figure who lurched around with huge wide steps, and didn’t need to speak for you to know that he was a star.

In another part of the limousine-escorted food stamp pickup Ol’ Dirty Bastard took MTV’s camera crews on in 1995, he stood outside of the welfare center and went on a stammer-filled tangent about his personhood.

“I’m in this rap game to get money,” he started, bearing the same aggression with which he reminded the U.S. Government what they owed him a segment earlier. “You know what I’m saying? I got babies…it’s time to take care of my babies. And I feel good… to be able to stretch myself and have my talent—to give my talent to the world and to the universe. So they can accept my talent and love it. Love it. You know what I’m saying? ‘Cause you ain’t gonna see no talent like this again in your life.”

At some points, Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s talent sounded a lot like a senile, perverted man moaning into a microphone for an unbearably lengthy mid-song interval. Other instances saw his talent manifest in the form of pissing on another rapper’s platinum plaque. In his case, talent wasn’t as much in the sense of musicality as it was audacity. There isn’t a living or nonliving soul capable of matching his uncompromising tumult; he had an unsurpassable ability to venture to the extreme of a spectrum—whether it be that of introductions, crime sprees, or award show stunts—and laugh out loud as the people in the middle hung on for dear life. Having the nerve to play a show while being hunted down by the cops is talent. Having the nerve to confront Uncle Sam with his failures is talent. Having the nerve to not give a damn is talent. And if you thought it was anything else, shame on you.