Founded in the early 2010s, Standing on the Corner makes music that spews frustrated confusion back into the face of the oppressive force that creates it. (ABOVE: From the music video for “SahBabii /\ Now, Nation End, 38:15” off 2017’s “Red Burns”.)

SAMUEL HYLAND

On the fictional 1933 afternoon that saw budding film actress Ann Darrow snatched from the high-rise hotel room she found temporary refuge in, dragged atop the Empire State Building by Kong, the monstrous runaway beast freshly escaped from a Broadway theatre, and forced to witness – from the antenna of what was planet Earth’s tallest building – the all-out fighter jet shootout that killed her estranged captor, two dynamics were at play. On one side of it, you had Carl Denham, the ambitious filmmaker. He took it upon himself to venture far overseas, onto the grounds of a native-occupied Skull Island in hopes of capturing the colossal being rumored to dwell there. Denham was known for filming in wild and exotic terrains. Skull Island, to him, was in no way as significant for its people as it was for its creature, the mythical life he could prove the existence of once and for all; the mysteriously interesting animal whose intrigue was just grand enough to make its bondage put cash in the pocket. So Denham’s ambition shone through the fates of what natives stood between him and his goal. When, after a long-enduring chase culminated in his promising young star actress being rescued from the clutches of this beast (now knocked unconscious with a gas bomb), and the entire crew were headed back to America to flaunt their catch, Skull Island was left in ruins. The shambles were equally physical and structural. With all the rampaging, shooting, fighting — violent conquest — that got an unconscious Kong on the boat back to America, his homeland visibly succumbed to warfare. At the anatomical level, Kong was the natives’ God. When the ambitious filmmaker arrived, the very first thing all passengers witnessed of Skull Island was the formal sacrifice of a woman unto the creature. He was who they prayed to, who they bowed to, where their infrastructure found its roots. Denham kidnapped the people’s religion.

Yet, the second dynamic at play was the one circling Kong himself. Beastliness, mythology, and monstrosity aside, he was a natural being. He was not man-made, nor was he accustomed to the things of Western mankind. All he knew was primitive. His sole experience with people was of having dominion over them. In place of skyscrapers, automobiles, and live audiences, he lived amongst trees, liana vines, submissive servants. And in the last days of his life, suddenly forced into a completely opposite lifestyle to the one he grew up in – now a shackled, name-tagged Broadway spectacle amidst a man-made urban environment of human beings who did not worship him – there was a point where rightful frustration boiled over. But to his captors, his confusion was wrong. He spent his final waking moments bullet-riddled, plummeting from the top of the Empire State Building.

Standing on the Corner, the New York City-based music group known for emboldened rejections of musical boundaries, seeks to tell through sound the authentic story of America’s King Kong: people of color.

“King Kong was this very natural thing trying to suddenly survive in a city, and not in a safe way — it was very violent,” founding member Gio Escobar told the FADER in a 2017 interview. “All of these things are intentional and connect to all of these things that are maybe not so accessible, but can only come from our experiences as black and brown people. I think these things we go through, if we don’t talk about them, we’re just going to be redundant, and not allow ourselves to progress.”

Standing on the Corner was initially born as Children of the Corner – a live act getting its namesake from earlier Harlem hip-hop group Children of the Corn. With the help of producer Jasper Marsalis, the project eventually grew into the still-expanding SOTC art ensemble realizing Escobar’s vision up to present day.

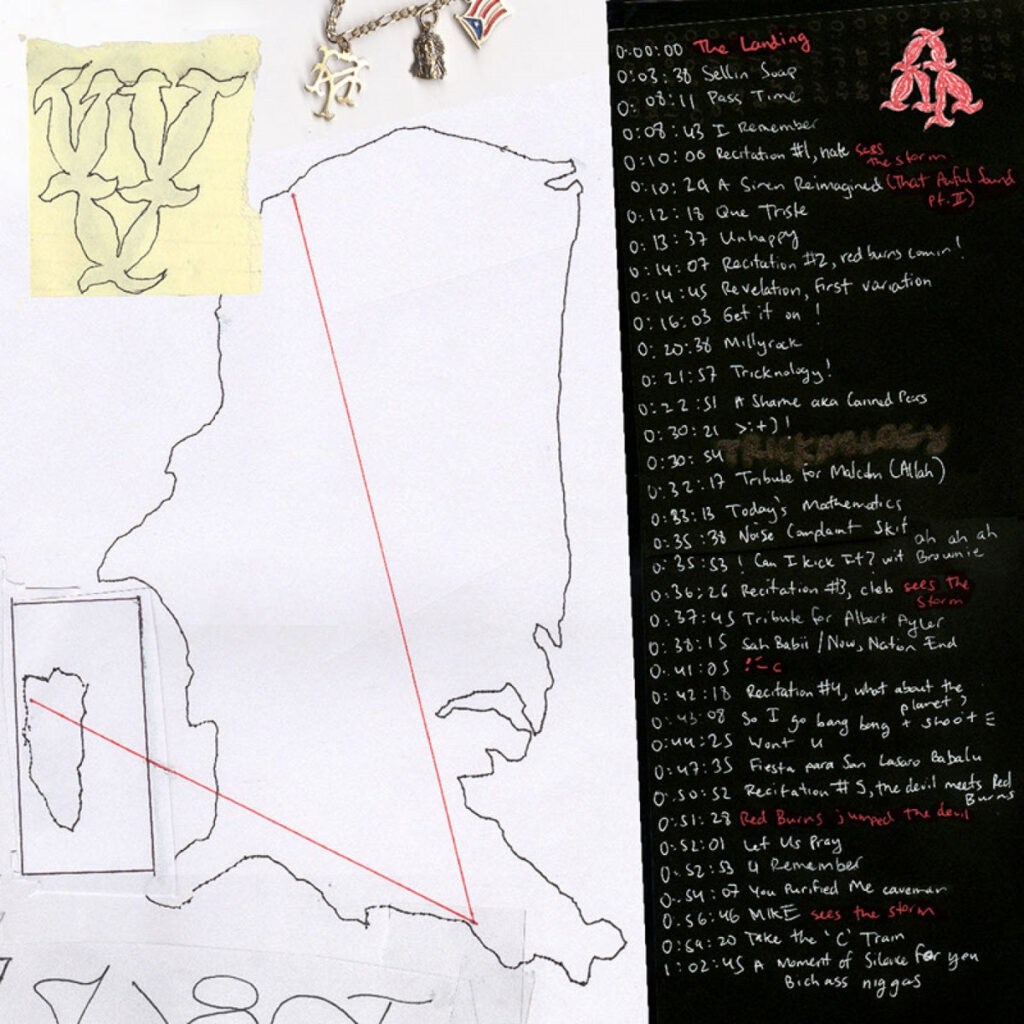

The way in which SOTC addresses what vital expression Escobar refers to is through music that defies all blockades upheld by what was once understood as art. Their debut release, a 33-minute eponymous EP enveloped with imagery of the Twin Towers and unintentionally released on 9/11, features slow-burns of seemingly directionless, slinky, reverb-waddled guitar backed by muffled percussion skewed by digital means; yet in the same record, there are points where full songs lasting only a few seconds consist of disoriented shouts followed by brief percussion solos and urgent panting. Their second album Red Burns – also unintentionally released on 9/11 – pushes the artistic envelope even further. Most starkly, holding over an hour of music, the tape is split into two 30-minute tracks entitled Side X and Side Y respectively. But even beyond that, the record’s content plays like one long idiosyncrasy. Red Burns is not meant to be understood in one sit-down – let alone at all. Each epistle in the two-chaptered saga is a brain dump of feelings, knowledge, anger, frustration — rightful confusion that festers in bursts of brief electronically rendered monologues, or indistinct bass lines serving no purposes immediately decipherable, or horn sections that make the entire situation twenty times more unsettling.

In Side X’s closing moments, there is a gradually sped-up (admittedly intensified) sermon given on the concept of “Tricknology:” a deceptive form of manipulation based upon intertwined honesties and dishonesties often analogically tied to the systemic mistreatment of people of color in America.

The narrator opens with ramblings of creatures.

“How humans use (tricknology!) against animals / we make the wolf feel pleasure in his own death / As far as the fish and the mouse go, we tricked them! / By showing them something they want, like cheese or a worm, just to kill them.”

But by the time the vinyl on Side X stops spinning, the disoriented, seemingly drunken babble becomes something much more relatable.

“Man abusing dope no different than the wolf who lick ice / and constantly, we’re fish craving a worm / nothing to stop the hook from getting in the mouth, because it been destined and this is how the devil fights / the art of tricknology is when we can’t fight the enemy, when you think the enemy doesn’t exist.”

A conclusive “Bruh!” wraps up the half-hour-long track.

One of the most familiar misconceptions about Standing on the Corner is their commonly misused “post-genre” label, most likely traced from the headline of a Pitchfork feature that came out about them some years ago. “It has to do with people thinking that it’s hip-hop, but not really,” Escobar told the Interview Magazine in 2019. “To me, it reads as something that somebody wrote about us, and then everyone kind of ran with it.”

In their purest form, the artists at SOTC’s core are in no way concerned with categories, let alone fitting into them — “post genre” included. The foremost objective, rather, is to emulate musically the confusion inflicted upon people of color by a society that stripped them away from Skull Island centuries ago, exploited them for money whilst forcing them to assimilate to an opposite world beneath the whip, punished them for their natural inclination to break free, then lawfully vilified their just agitation.

The authentic sound of such resistance is music unbound to borders. Besides regurgitating distress to the very force that spews it, rejection of genres signifies, in addition, rejection of systems put in place to somehow organize true feeling: The same way one will never gain individual hockey skill of his own by exclusively watching Datsyuk highlights in an attempt to make their game match exactly, an artist will never truly translate the complete gamut of their soul onto the canvas – a challenging task in itself – with the looming presence of genres snowballing unrelenting, unnecessary pressure to force whatever comes of the creative process into a preset box.

In a musical world structurally defined by genres, resistance of the like is excessively difficult. Given that the substance of music is understood by means of its categorization, a lack thereof incurs repercussions more often than not – and in the vast majority of cases, careers are on the line.

One common penalty is being labeled “experimental.” If the contents of your soul aren’t catchy enough to be pop, gritty enough to be hip-hop, distorted enough to be rock n’ roll, homey enough to be R&B, acoustic enough to be country, digital enough to be dance/electronica, Carribean enough to be reggae – they are cast into the obfuscated pit called experimental: sounds too weird to possibly be palatable at the mainstream level; melodies so strange that the artist just had to be experimenting in that expensive studio. The tracks are given their own chart. Rather than the songs clearly fitting one mold, yours receive limited radio airplay. Your explicitly categorized label-mates get regular press from esteemed publications, while you’re happy to field the occasional interview request from pop-up WordPress websites that earn a majority of their circulation from small indie fandoms. The culture surrounding your followers becomes one of arrogance sugar-coated in the self-proclaimed prestige of “knowing real music.” Your creations are likely forgotten when you die.

Confusion is at the root of all art. There is a general unsettlement that gives one the urge to pick up an electric guitar, just as there is an internal dissatisfaction with something either inside or out that tells the mind to tell the arm to pick up the paintbrush. The underlying infrastructure of society is no different from the underlying infrastructure of the record industry: confusion, rather than something to be embraced (as it is inevitable in both settings), is something to be frowned upon. Then, if it doesn’t stop – penalized.

“How do you capture an emotion, but not lie to someone?” now-departed founding member Slauson Malone (Marsalis) muses in the aforementioned 2017 FADER interview. “I feel like that’s a huge issue in songwriting. At a certain point, you have to create this emotion that has to be consumed by people who are listening.”

Big L of Children of the Corn made it a huge point to understand exactly who he was talking to and when. On songs like ‘98 Freestyle, the gritty posthumous deep-cut immortalized by an added Jay-Z verse, he directly addressed his enemies when hurling ultra-personal grenades: “You was never shit, your mother should have swallowed you” got an audible “mmm” out of the radio host present. On tracks like the hyper-realistic warning that is Street Struck, he spoke earnestly to Harlem’s youth on what dangers ensued lifestyles like his own. “Their life is twisted, and most of them are quite gifted,” he rapped, referencing ill-fated members of the target audience. “In other words, they got talent / but they’d rather sell cracks, and bust gats, and run the streets actin’ violent.”

Much like Big L, Standing on the Corner knows very well what crowd they intend to reach the ears of – black and brown listeners with which an empathetic binding is pre-set. It is in direct communication with them through mutual frustration made audible that the group establishes their rebellious position outside of the complete scope of genre-based music. No label – “post-genre,” “genreless,” nor “experimental” – is applicable. SOTC has nothing to do with categories, and everything to do with communication. It’s okay to be confused. The latter must seem so for people whose confusion, though justified, is demonized, and Standing on the Corner wields its own outrage as a weapon in making this come to be.

But moreso, mere delivery of truth is what the SOTC art ensemble bounds towards with its musical vision. And truth, though simplistic in theory, becomes very complex when translated from soul to studio.

Red Burns was crafted on the premise of an extensive search for honesty in its purest form. It is a journey widely epitomized by how the title of its final product grew to fruition. For a while, he told the FADER, Gio Escobar sat with the titular motif, dwelling on it solely because he had liked the way it sounded – until on a trip to his homeland in Puerto Rico that spring (2017), he got into a series of discussions with family about why everything was the way it happened to be.

“That’s what Red Burns is – it’s a curse, that I think people of the diaspora have,” he says in the interview. “I guess the root is, ultimately, Manifest Destiny – this willingness of colonial white settlers from Europe who chose to violently alter the history of another people for the rest of time. We can never undo these things.”

In Escobar’s own case, the scarlet, shackle-imprinted welts that last from Manifest Destiny – the diasporic curse – are deeply ingrained in his culture. Christopher Columbus arrived onto Puerto Rican soil in 1493. From there, despite what religious systems were established by natives, he sowed permanent seeds of Catholicism, first naming San Juan after the biblical figure John the Baptist, then enforcing mandatory catechisms that became violently implemented cultural rites of passage. The first encomienda system was founded. Massacres were carried out in the name of God. Noses, hands, feet, fingers, ears, genitalia were sliced off as punishments for not doing the virtually impossible. Women were paraded naked through the streets to be sold into slavery. Then, when the gold was collected, he departed the cities he ravaged as casually as he came, boarding a boat back to his people en route to please them with the loot.

It’s very similar to the story of Carl Denham, the ambitious filmmaker. Just as Denham ventured abroad to breach indigenous Skull Island land in search of valuables worth stealing, Columbus did the same with Puerto Rico: both, at the end of the day, left with bloody footprints, stolen religions, infinite atrocities gone unpunished, and all of the glory.

Red Burns’ creation process, much like the putting together of its title, was an ongoing conversation with context. The context that made (and still makes) the music take on meanings beyond a series of vibrations; the context that defined each individual of the ensemble as a story to be further amplified within collaboration; the context that constructed the very city SOTC finds a creative synergy within — there needed to be introspection in order for there to be output, the crux of which was someday destined to be context for another cycle.

“This is more of a neutral way to address issues,” Marsalis said. “These things already have meaning, we don’t need to make more shit, all that needs to be done is contextualizing, and that’s what this mixtape has done for me.”

Akin to the group’s music itself, Standing on the Corner treated Red Burns’ rollout-slash-contextualization process as a living, breathing, entity that could find its heartbeat in various streams. With the help of AINT WET, a Red Hook-based print establishment and mutual friend of SOTC’s, they built a website surrounding their release – standingonthecorner.com – that featured an expansive collage of internet memes signifying black frustration. The gallery featured GIFs of children throwing enraged tantrums, Spiderman cartoons annotated with the words “NEW YORK SUCK MY DICK,” African-American children crying hard at household computer desks; “If we had to choose a thesis for the [mixtape], Escobar said of the fit-thrower, “it was that kid.”

Every aspect of Red Burns’ release is emblematic of how it’s creators operate: they are a conscious group of forward-thinking individuals just as fixated on the past as they are on what’s to come, very much responsible for hoisting their collective culture forward, yet not afraid to admit the weight carried by yesterday.

Standing on the Corner’s last project was a three-track EP entitled G-E-T-O-U-T!! The Ghetto, officially released this past July. Musically, it’s fairly straightforward for an ensemble that spent so much of its past emanating unapologetic confusion yet to be decoded. In place of unsettling oscillations of computer-processed flat notes, there is a steadfast bassline. In place of muffled, improvised percussion independent of all other in-track elements, there is a stable drum pattern that breeds a comfortable pocket to be shared with other melodies. Lead vocals are handled by seven-year-old Annalise Chanel Renee Williams – the only lyrics, aside from rhythmic breaths of air, are the rallying cry “Get out, out the ghetto,” and “Nobody knows,” repeated six times in the song’s denouement. As the song is performed live on stage in its nine-minute music video, lights flash, revealing in bits and pieces a tightly-packed congregation assembled before the stage, waving emphatic hands between camera cuts and convulsing with the atmospheric pulse led by the hopping young vocalist.

In its most simplistic form, aside from tonal or thematic significance, a ghetto is defined as a run-down part of a city typically occupied by low-income minority groups. But the ghetto can also be mental. Just like any urban version, a mental ghetto finds its essence in the depression of being stuck forever. It’s a looming feeling, an eternal sensation of impending doom. And just about all of the time one finds themself in that headset, it’s the direct result of some form of displacement. A breakup. A death in the family. A job interview gone sour.

Although to heed the young singer’s instructions – to simply “get out” – is to identify the displacement and undo it, there are certain displacements that cannot be reversed.

Like that of King Kong. Miles away from his homeland, enslaved to an environment that thrived upon his exploitation, he grew frustrated as all living organisms would be naturally inclined to in face of oppression. Physically, he was New York City’s newest fascination: nowhere near the socioeconomic ghetto. Mentally, yet, the slums existed in displacement – when am I going to see home again? He was never able to escape that. The ghetto ate at him. He rampaged, dying a brutal death at the hands of his oppressors, holes in his story parallel to the holes in his carcass.

Standing on the Corner offers through art a true way out of the King Kong-esque ghetto people of color in America have faced ever since the first slave ship docked: confusion. With records that bottle up boundless torrents of built-up rage in packages that are unrepentantly unfathomable, the collective prove that there is a freedom in not making sense. Power does not have to be palatable. The soul does not fit into a box of any sort – racial, genre-based, categorical – and for everyone on planet Earth, the box is the ghetto that must be gotten out of.