THE UNIVERSE WANTS RYAN HAWAII TO SUCCEED.

With his debut full-length musical offering set to be released by the end of this month, interdisciplinary artist Ryan Hawaii reflects on the hope, influence, and do-it-yourself attitude that fueled his rise to the top.

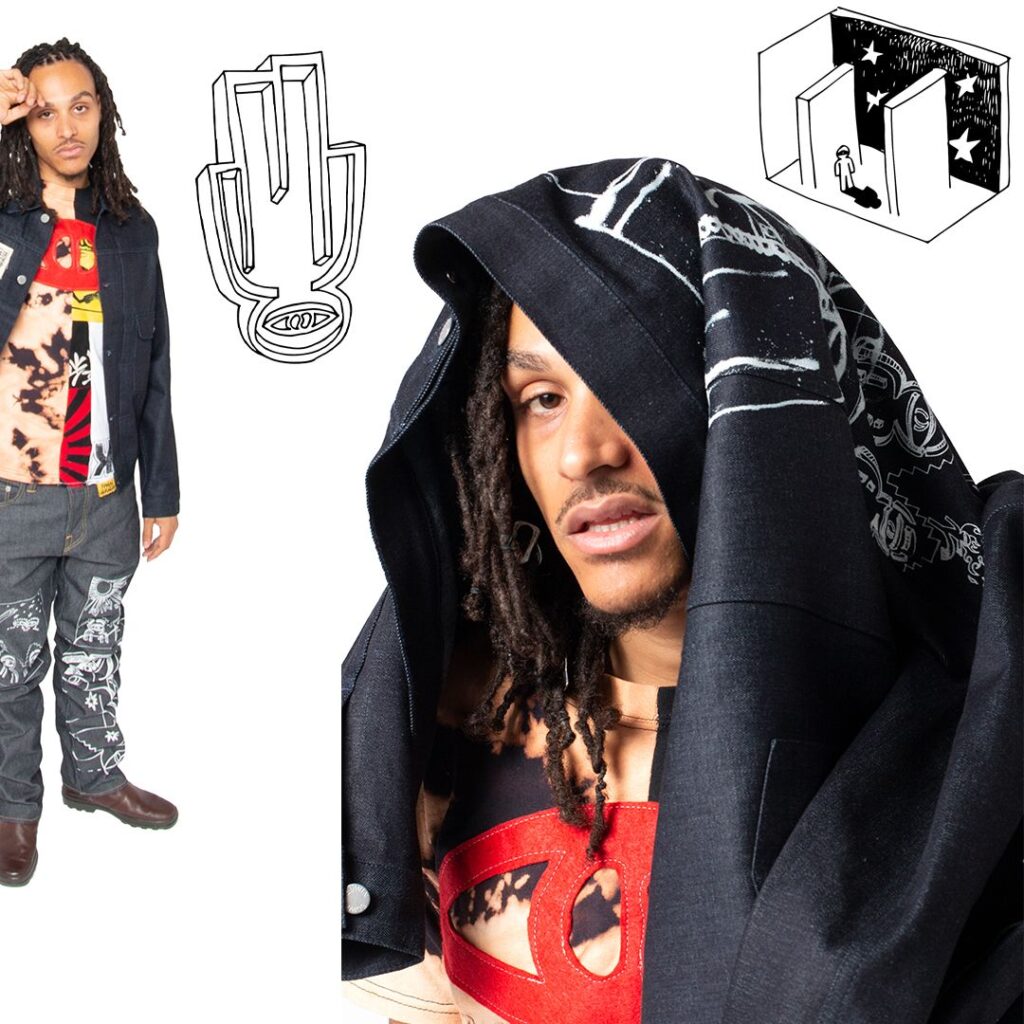

PHOTOS: Jonas Martinez; Brynley Davies

THIS ARTICLE IS BEST VIEWED ON MOBILE DEVICES.

SAMUEL HYLAND

“So, basically, the universe wants you to succeed.”

The UK-based interdisciplinary artist Ryan Hawaii is lounging on a couch, head propped up against an opened palm, as I question him about an interesting take on optimism brought up in a prior interview of his. With eyes that seem to interrogate his surroundings with every restless arc, he sits awhile until the right words come to mind.

“But… it’s like this secret that not everyone knows. It’s like- there’s a lot of people who don’t have that awareness that the universe wants you to do well,” he eventually concludes. “There’s definitely been many signs that the universe has given me to let me know that I’m on the right path. I just always try and heed them when I can; keep aware, listen for it.”

The approach is one that has silently furnished the artist’s rise to international acclaim over much of the 2010s: in face of whatever hardships were presented by society, he quickly found that once his eyes remained fixated upon all perceivable confirmations of fruitful hope, small faith would eventually be rewarded. At some point in the period between his graduation from secondary school, and his decision to ultimately forego college in pursuit of full-time artistry, for instance, he held down a job selling snacks to audience members at London’s Chelsea Football Stadium. On one of these days, he returned to his locker after work to find his phone blowing up with messages and notifications. “I went into my phone and stuff – and you know how all the endorphins are rushing,” he recalls mid-conversation, a chuckle steadily working its way out. The prolific grime MC Skepta had posed in a hoodie of his for an Instagram post, and tagged him in the photo. Up to that point, Hawaii’s consumer circle consisted almost strictly of his classmates. “That was the first time that he (Skepta) ever wore anything of mine. I remember thinking, like, That’s mad. Like I can really do this.”

When I speak with Ryan over Zoom today, he’s well settled into another thing he’s just remembered he can really do: chill. It’s about 8 PM in London when our chat begins. Earlier on, he tells me, he attended a music video shoot for the multi-instrumentalist Wu-Lu, an artistic colleague of his, at a skatepark somewhere in Hackney – and over the typical 24-hour stretch, there is much more on his plate: for at least five days each week, he’s hard at work in his studio on all things ranging from clothes to music, both for his own projects and for those of his various ongoing collaborations. As of right now, though, there is no further hustle to be upheld for the evening. He’s at a small gathering in a friend’s house, the remainder of the night all set to be spent with those closest to him. “This is actually one of the most chill, social days I’ve had in a while,” he grins, dapping up a peer off-camera. Among detectable ambiences in the background throughout the entire Zoom call, there is bubbly chatter; faint music; an overarching sense of home. The warmth seems to permeate the screen.

As it stands today, it would be difficult to say that his habitual compromise of social life for sake of work has been in vain. At 25 years of age, the artist, born Ryan Williams, has pushed forth an eclectic creative career versed equally in music, fashion, physical art, and production, with his widespread bearings having previously landed him on the radars of figures including Virgil Abloh, Cardi B, Lil Uzi Vert, and Playboi Carti. His debut full-length musical offering, a five-track EP entitled NOMAD, is set for release by the end of this month. When he’s not busy with music – whether having his designs stocked in Selfridges, easing afro-punk culture back into the mainstream via NTS Radio, or reincarnating the likes of Basquiat and Duchamp – it can best be assumed that he is widening his creative scope in some other hyper-impactful mass capacity.

“We manifested that. Because that’s what we wanted.”

The duality between Hawaii’s restful and restless sides is one that – coincidentally, considering the site of today’s Wu-Lu video shoot – saw its primitive roots develop over childhood skatepark trips taken alongside his grandmother. Seeing the skateboarders then, alongside being deeply invested in a thriving little-league soccer career, deeply resonated with an innate quality he would eventually trace to artistic leanings. It would not be long, either, before such a sensation would manifest itself on an exterior front. “The way I loved football was like the way I love the shit that I do now,” he tells me, semi-laughing. “I was very obsessed with it, like reading the books and all that kind of shit. I would play my games – like when I had my matches – and I would go home, and I would have a little book. Then I would write the results. I would document who scored. I would draw diagrams. I would draw myself playing in the matches. I would make, like, little football cards. It’s like, you see these things reflected outside of you in the world… and it sort of validates what’s going on within you.”

The uglier face of this dynamic would reveal itself chiefly as a symptom of Hawaii’s surroundings. Hawaii spent the majority of his youth in Catford, a dangerous, less-affluent ghetto of South East London in which muggings, robberies, and murders were among commonly reported crimes. When I question him further about the reflection of one’s inner being via the outside world, he tells me a dictum he was forced to learn firsthand, on the streets of Catford, at a young age: “The energy you put out – into your realm, into your existence, into your world – is what you get back.”

The first time Ryan Hawaii was mugged, he was standing outside of a local chicken shop. He had garnered a reputation for selling snacks to his fellow students for money, and this day had been a particularly big one for business: his rugby team was just coming off of a lengthy match, and by the time he left the company of his hungry teammates, he had earned himself a pocket bulging with cash. Outside of the store, he was approached by a bigger man who began to ask him what he was planning to buy.

“I was like oh, nothing, nothing, you know- I acted like I wasn’t going in there,” he tells me. He recalls the story in a slow-paced stream of consciousness, long pauses evolving into steadily steeping suspension. He gazes off into a corner as he brings the nitty-gritty of it back from memory – from the genesis of how he nervously denied his robber, to his gradual transition from denial to hesitant appeasement, then ultimately to a loose recollection of approximately how much of his earnings the man left with. “He kind of put his arm around me – not in a very violent way, but just trying to manipulate me – and long story short, first it was 50p, then it was up from there.”

A later time he was targeted, in stark contrast, he knew exactly the energy he had to put out in order to get what he wanted in return: in this case, to go home with all of his money. The stakes were much higher on this occasion. At a bus stop, Hawaii and his friend were confronted by a short young man – seemingly not big of a threat – who approached them after getting off of a bus. After an initial brush-up with the pair, he walked away. Five minutes later, he came right back.

“He approached us and was like What ends you from? What ends you from? And we were like What? Like ‘what are you on?’ kind of thing – because he was smaller than us – and there were two of us. So we’re kind of like What? So we both stood up, like we were ready to fight this guy.”

But what the offender lacked in height, he made up for in weaponry. Within seconds, he lifted his shirt to reveal a glistening butcher’s knife. Hawaii’s friend retreated.

“I was more willing to fight this guy though,” he tells me, now. “My mind didn’t process running away until my friend was all the way down the street.” Although he did wind up escaping with his friend at the end of the day, it was not as much about victimizing himself as it was about ensuring the protection of his colleague. And, while there was no superhero movie-esque physical altercation – one that could have ended much worse than it actually did – there was also no money lost in the incident.

Having grown up in such a climate, Hawaii says, in addition to making him increasingly resilient, influenced his artistic output to an extent that sees reflections of it appear both intentionally, and subconsciously, in the art he produces as of today. ‘OWN WORLD,’ the first track on his forthcoming EP, for instance, seeks to expand on a concept the artist resonated deeply with when he heard it represented on Kendrick Lamar’s Good Kid, M.A.A.D City (2012): that one can possibly be from the ghetto, but not be the ghetto themselves. “At that time, there weren’t many voices in hip-hop that were coming from that perspective of, like, not being gangster, or not being in that lifestyle, but being around it,” he muses. “Just growing up in the hood, but not being in that world – being in your own world, you know?”

“I could sit here and explain all these ideas and deep theories behind my work, but really – at the crux of it – if you can look at something simple, and it speaks to you, and you can interpret it in whatever way you want, that’s the most beautiful thing to me. The viewer is also a part of the work.”

It’s a concept that seems omnipresent in creations of his across various disciplines: Ryan Hawaii exists within the world we share, but he lives in a world of his own curation, with his genre-spanning creations serving as a live reckoning between the two. At some point early on in our chat, for example, he cuts himself off mid-response to rise from the couch and show me a pair of self-designed jeans he’s wearing, made in a recent collaboration with the Japanese denim engineering brand Edwin. One leg of the jeans bears a minimalist painting of a serene night setting, starry skies beheld by a calm figure standing atop a pyramid. The other leg of the jeans features the same man, atop the same pyramid, this time positioned beneath a raging sun. His head is on fire.

“That’s one of the symbols that I draw that represents, like… being very- it’s like your mind is on fire. It’s just infused with ideas and whatever else is going on; highly charged,” he explains, asked what these things may mean. The artwork, he goes on to tell me, was a direct response to a period of deep thought prompted by his then-girlfriend and Kanye West enduring mental episodes around the same time. “I try to reduce these concepts to a very simple form.”

Hawaii reveals later on in our interview that such primitive simplicity is an approach he adopts in major part from one of his most vigorous influences: Jean-Michel Basquiat. Basquiat, he explains, rose to his groundbreaking stature as a byproduct of his willingness to allow for a sense of intimacy accessed by removal of complex forms. Over the course of his short-lived creative surge, the issues he addressed were composite as lone entities – racial divides, socioeconomic disparities, poverty writ large – but the imagery through which he carried such weight was elementary enough to not only be consumed, but to even greater effect, exist timelessly as an open forum. “He’s making shit simple,” Hawaii mentions at one point, sitting up. “And that’s what I think art should be. I could sit here and explain all these ideas and deep theories behind my work, but really – at the crux of it – if you can look at something simple, and it speaks to you, and you can interpret it in whatever way you want, that’s the most beautiful thing to me. The viewer is also a part of the work.”

“I just try to have a good impact on all those around me. I want them to know that they can do it.”

As he touches upon this concept of accessible creativity over the course of our interview, a term he comes back to time and time again is “punk.” A second reason for which he drew inspiration from Basquiat was that he embodied punk culture via utilization of his work to exude defiance – just the same way Marcel Duchamp, another high-ranking inspiration of his, boasted similar gut by submitting a signed urinal to an esteemed art gallery in 1917. For Ryan, the concept of punk transcends just the rock & roll subgenre. Rather, it is a central attitude from which he addresses all that lies ahead; a sturdy ‘go-get-it’ dynamism that builds its own chair when it isn’t offered a seat at the table.

One of the most fateful flashes of such a construct came in 2015. After collaborating with fellow UK-based designer Apex Jai for a small pop-up shop in a store in East London – attended by Skepta, among other MCs on the scene – he sought to do something that would further solidify the statement he intended to make long-term. He got to work on new pieces, filling up a bag with them, then posting them onto social media to promote a low-key accompanying operation that was slated to be held at Selfridges. “Loads of people thought it was a party,” he recounted to the FADER that year. “But they all RSVP’d to my email and I replied with the details, telling them it was in Selfridges, and not to approach any members of security because it was not an official thing; it was like some military kind of scheme.” The plan was to hijack Virgil Abloh’s Off-White installation at the store, then force him to take notice by relentlessly tagging him on Instagram and Twitter. The gathering was initially broken up by security. But later on that evening, Abloh followed Hawaii on Instagram – and since, the two have fostered a synergetic partnership that most recently saw Hawaii invited to speak at a highly sought-after fashion workshop of Abloh’s, later going on to conduct two in-store activations customizing Off-White pieces in London & Manchester’s Selfridges locations.

Hawaii’s punk-inspired approach to his work has manifested itself just as well, too, in its aesthetic front. He’s excited to recall stories about his days in the Neverland Clan – a now-disbanded rap supergroup made up of himself, Daniel OG, Omelet, and Okimi – when the concept comes up in a response of his. “A lot of our strength was based off of live shows,” he tells me, matter-of-factly. If you search for the term “Neverland Clan” on Spotify, you won’t get any results – but in the scene they called home, the essence of their live sets alone was enough to garner them a cult following. “We were a group that were really bringing that punk energy back to the black community. Like mosh pits and shit. Jumping in the crowd. That kind of shit wasn’t going on in London – I mean, obviously rock, of course – but not in a hip-hop space. We were pioneers of bringing that energy to fame.” The afro-punk revitalization did not end with the Neverland Clan either: when Skepta began wearing a padlock chain gifted to him by Hawaii at the height of his Konnichiwa-embodied punk-adjacent phase, several rappers soon began to catch on – some, even, going on to admit to being influenced by the move later.

Such anecdotes only serve to accentuate the overarching artistic standpoint from which Hawaii creates: it isn’t as much about doing it so that consumers like it, as it is contingent upon him, himself, reckoning it with his own spirit first. Much like the punk culture he emulates writ large, it is an ethos that fundamentally requires going against the grain. The direction of hip-hop fashion currently gravitates heavily towards an infiltration of high-end affluence years in the making – the typical press shoot boasting thousands of dollars’ worth of big-name pieces by the likes of Gucci, Givenchy, Versace, and others – with the lifestyle suggested by such attire gradually overtaking the rags-to-riches gospel of rap music’s gritty beginnings. To take the independent route of Hawaii is to subvert a seemingly unbreakable system from its root: for every milestone the artist surmounts en route to international success, another pebble is thrown into the glass ceiling of exclusivity in hip-hop couture. The ceiling will not, by any means, come crashing down in pointy shards tomorrow. But if a 25 year-old independent designer from London can manage to turn a seemingly futile Selfridges raid into an impassioned endorsement from Virgil Abloh, what message does that send about the future? The grandest Goliaths are toppleable. And until the pebbles run out, every shot at the impossible is worthwhile.

For Hawaii, all of this comes down to hope at the end of the day. And not only hope for himself – but hope for the people he surrounds himself with. No matter how long it takes to do so, he finds that belief in oneself will always manifest its fruit in some way, shape, or form, as long as whoever bears it refuses to relent. In one example he recalls from his stint in the Neverland Clan, the quartet sat together to contemplate their collective future. “We were just sitting around, talking and stuff, kind of having a team meeting in a way- we were like Man, we’ve been in the UK for too long. We’ve gotta travel, see other places,” he recounts. “And literally – a week later – we got an email from Adidas and Complex magazine about doing a promotional tour for a new Adidas shoe.” Among other destinations across the globe, the group were flown out to Paris, Milan, Amsterdam, and Berlin. “We manifested that. Because that’s what we wanted.”

Even more so, in one studio session with Slowthai, the two talked deeply about confidence issues that were to be grappled with. “I told him: If you keep thinking that you’re a genius – and believing it – then you will become a genius, because that’s the energy you’re washing yourself with,” he recalls late in our interview. “I always try and give people their flowers; charge them up, put a battery in their back, you know?” As of right now, Slowthai’s most recent LP Tyron (2021) has peaked at number 1 on the UK’s album charts. It is the only album of his to ever rank above 9th.

As Ryan Hawaii sits at the forefront of a brewing charge against widespread inaccessibility in high art, it becomes more and more apparent with time that not only does he have the talent to go about such a grind, but also the unwavering conviction to follow through. If Virgil Abloh, Slowthai, and Skepta are any group to attest, it can be verifiably said that he has never truly wronged himself by continuing to work in spite of any lack of support – but when that support has been there, only big things have resulted.

At one point in our interview, I mention something about how he maintains his optimism in spite of factors that constantly seek to poke away at it. He is quick to protest the way I phrase this.

“Don’t get it twisted,” he starts, a hand grazing the dreadlocks behind his head. “There are times when I think the world is against me.”

He takes a second to ponder, searching for the words in mid-air, occasionally opening his mouth as if to say something, then closing it again to think a bit more.

“It’s just a test – about maintaining a good state of mind – which is something that I have to work on,” he eventually concludes. “But I just try to have a good impact on all those around me. I want them to know that they can do it.”

Q&A

Because of internet-related issues, this interview wound up being cut significantly short when it first happened via Zoom. Sammy’s World asked Hawaii the remaining questions via email. You can read his answers below.

SAMUEL HYLAND

RYAN HAWAII

We were talking a bit about this distinct period in which your work started gaining a lot of recognition from big names – what kept you going before people started taking notice?

It’s tough to truly know….faith I would say. And an inbuilt knowledge that I was meant for more. Not just the conventional 9-5 life.

Your latest one-of-one collection bears the title “Conversations With Myself.” What does that mean to you, and what makes it significant to you as well?

I feel that there is this on going dialogue between me (the person) and my artwork (the exterior manifestation of me) and there is an interaction between those two entities that transcends time, and presents itself in space (physicality). That’s on one level. The other being that all of the pieces in that collection were directly inspired by conversations with friends of notes that I made from random thoughts I be having, they are represented by text on the pieces.

With music, how did you overcome your initial fear that no one wanted to hear what you had to say?

That fear still exists I guess…what I talk about in my music are real things that go through my head & happen to me in my life. Not much bravado, which is the status quo in hip-hop. But now I’m beyond the point of caring, I believe that my music should exist outside just my privacy, I’m ready now.

Tell me a bit about your EP releasing at the end of the month. What do you want the listeners to get from it, and what are you getting from it thus far?

Yeah, I’m releasing NOMAD my debut solo music release. It’s mad. A long time coming. I want listeners to see a facet of themselves reflected in it, I want them to enjoy it, play it with their friends, their partners, at parties, in headphones alone in their room, I think there’s a song for every scenario on there – a good taster for what’s to come from me musically.

With your work, in all disciplines, what do you want consumers to take away at the end of the day?

I want them to understand that all my works represent me, but also a way of thinking and a specific approach to creativity – everything is a stamp I am leaving on you, an impression built to last.

As hip-hop culture moves more and more towards big-name brands and high fashion, what place do you see your kind of independent work having in it going forward?

I will be a big brand too someday, it’s just filling in the steps in between. I would love to hear more hip-hop artists name dropping independent brands though, not only Gucci or Louis etc. The underground must become part of the lexicon, otherwise it’s boring, you just sound like everyone else.

You said in one Instagram caption that you concluded that you were not from this planet. Tell me more about that.

Some of the thoughts and phases I’ve been through, and the innate feelings and vibes I’ve encountered from humanity at large, sometimes has me questioning existence or my own origins. I’ll find the mothership someday….