The World’s Fair spitter navigates a scorching Friday in New York City, and talks about social media, high school rap battles, and making it happen for yourself.

SAMUEL HYLAND

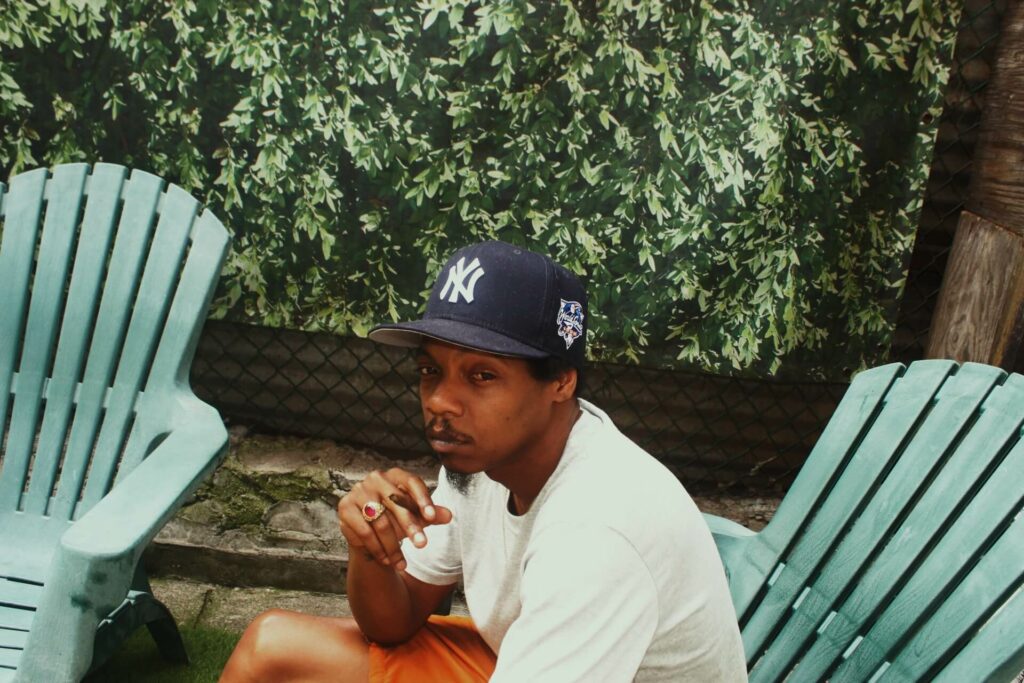

At about 3 PM on a July Friday in Tribeca, it’s oppressively humid, and outside of Scarr’s, a longstanding storefront pizza haunt that leads into a dimly-lit bar area, a small crowd of about a dozen chuckling influencer-types have formed a haphazard line, much to the dismay of an annoyed server who tells them they can just place their orders indoors. Straggling somewhere behind this assemblage are Remy Banks and his longtime friend Reni. Banks emerged onto New York’s underground hip-hop infrastructure in the mid-aughts, crafting a niche reputation among internet-savvy listeners with the swaggerously traditionalist, old-school-meets-new-school flows he spat as a member of the city-bred grassroots hip-hop collectives World’s Fair and Children of the Night. He and Reni are each wearing vintage New York Yankees fitted caps, with patches boasting World Series pennants hoisted by rosters of now-retired pinstripe legends decades ago. Aside from the cap, Banks is wearing a gold chain with a modest pendant shaped like the Yankees’ logo, a gray T-shirt, orange Stussy swim shorts, hidden socks, and a pair of choice Nike ACG Air Mowabbs in New York Knicks colors.

“It wasn’t really like a long process. Just more so like Alright, the semester’s almost up… Am I going back to school next year?”

When Banks spots me working on a pepperoni slice in Scarrs’ outdoor seating area, he can’t decide whether he wants to get something from the pizza shop so he doesn’t have to do the interview on an empty stomach, or forgo the unbearably long line and stick it out. He and Reni convene for a bit, and before I can get my bearings together, we’re off to Cheeky Sandwiches on Orchard Street, my tape recorder, half-eaten pepperoni slice, spiral notebook, cell phone, portable charger, and canned Coca-Cola equally on the verge of spilling out of my hands. Banks commands the streets with the chill, playboy-adjacent cadence of your favorite uncle, who talks about Nas at the barbecue, and also happens to be a low-key community staple. When a young woman smiles through a “Hi Remy” in passing, he flashes a grin not unlike that of Drew from Everybody Hates Chris, and swags out a smooth “How you doing?” followed by a “Hope you’ve been well.” Most people ostensibly either know him or know of him, and although he has every reason to embody the grand image his music commands, he seems much more content to blend in with his surroundings. It feels like it would take a lot to get on Remy Banks’ bad side. When we get to Cheeky Sandwiches, he greets the cashier as if the two shared a womb together — needless to say, he appears to be a regular customer — before poring over the menu and settling on a fried chicken sub.

Seated next to one another at a waiting bench near Cheeky’s entrance, Banks and Reni share a look, then a knowing guffaw, when I ask how long they’ve been friends. “Shit… like, 2008?” Banks says. In what context? “Being out. Being downtown. I met Reni hanging out downtown and shit. That’s how basically all of World’s Fair got together.”

The intersecting lore of World’s Fair and Children of the Night is rife with similar stories of days spent “being out,” many of which Banks vividly relays as we walk out of Cheeky Sandwiches, and into the sticky streets of Chinatown. Much of Banks’ sonic origin story can be traced back to a pivotal battle rap competition held during his first year at a local high school, which he begins telling me about in the sandwich shop, and spends most of our walk outside running me through. “Some people knew I rapped, but I was just rapping joking around and shit; I would have freestyles that were, like, instrumentals or whatever,” he starts. “Then out of nowhere, this fucking dude Cody, he was, like- everybody knew Cody. He had braids down to his calves, he had the baddest chicks braiding his hair in the cafeteria… that was Cody.”

Put on in conjunction with the school’s fall dance, the prize for winning the rap battle was a copy of Jay-Z’s The Black Album, which had just come out. Being the scrappy, natural-born spitter he was, Cody had somehow made it to the final round, and was taking down an entire collective, one by one, on his own. “Yo. He was just going off, but his bars, they were crazy compared to what these dudes was talking about,” Banks says, projecting his gravelly inflection over bumping Chinatown traffic. “They talkin about ‘clapping,’ I’m gonna clap you up, I’m selling bricks, I’m selling this, and it’s like, no you not! We in high school! And Cody was talking about shit that makes you think. And everybody was like Yo, what!”

Cody ultimately wound up being disqualified from the rap battle upon accidentally breaking its strict no-curse rule, but the school gave him a copy of the album anyway. It wouldn’t be Cody and Banks’ final interaction. “I knew that he rapped, and he heard that I rapped, but I never really put it on public display or nothing,” he says. Cars are honking loudly now, and we’re walking down Canal Street, towards a busy intersection en route to Banks’ favorite smoke spot. “I wasn’t into no rap battles or nothing. I was always very quiet. Like, real timid with my shit. Really, really timid with my shit. And a few years later, after high school, I ran into Cody. He was interning at Columbia at the time. I was on my way to work; I worked on Fifth Ave. I see him, and he’s like, Yo! You still rap?”

“New York was quiet for a while. After G-Unit, the early 2000s, there was really nothing here. If you wasn’t signed to a major [label], you were underground.”

Cody told him about Children of the Night — of which he had been a member — and invited him to record with Lansky Jones, another of the collective’s founding MCs. “I’m like, Lansky… Why do I feel like I heard this nigga name before? Then I’m like Oh shit, I was just with this nigga two weeks ago! Him and Nasty Nigel. Nigel and Lansky had pulled up to my boy’s crib with this other kid named Dennis, who I also went to high school with. Dennis is the same cat that introduced Cody to Lansky and Nigel.” When Banks made good on Cody’s invite to the de-facto Children of the Night headquarters, the collective had already been anywhere from several months to a year old, and all he could do was take in the room and admire. Eventually, Cody invited Banks to his own place to record a song, and, upon finishing it, jumped to show the rest of the group. “Cody played it for everybody and was like Yo, I think Remy should be part of Children of the Night,” he recounts, with a chuckle. “And everybody’s like Yeah Yeah Yeah, and Children of the Night became a collective- You still want that?” He breaks the storytelling trance to gesture towards the uneaten second half of my pepperoni slice, and, once I realize aloud that I probably wouldn’t have time to eat it mid-interview anyway, he laughs and points me in the direction of a garbage bag leaning against a nearby lamppost. Listening to Remy Banks tell stories — of which he has many — is a lot like hearing your too-cool older brother run you through neighborhood folklore while walking you to school. (For the record, Banks is, in fact, a too-cool older sibling: when he points his lanky 16 year-old brother out to Reni and I in a family photo on his phone, the most striking realization behind their visual similarities is their difference in height. “Yo,” Reni laughs, “You got dunked on!”)

At about 3:30, we arrive at a tall staircase that leads up to a set of shaded doors. Banks goes upstairs, rings a bell, and makes a few phone calls, while Reni and I wait at the bottom. A few minutes later, to the tune of a homey “There he is” from Banks, a van pulls up, and emerging from it are a middle-aged bearded man in a Mets cap, and a pleasant older woman who takes a moment to get a few things from the trunk. After exchanging pleasantries and introductions, the pair lead us up the staircase, through one of the doorways, then up another staircase, and into a cozy members-only club with large windows and brick walls. Decorations on the walls include a skate deck emblazoned with Curtis Kulig’s Love Me iconography, a large cubist painting, and a smattering of ornaments a cultured grandmother might have lined up across her windowsill. The man in the Mets cap, who owns the club, gives us the hospitable make yourselves at home rundown, fiddles with the AC, shows us how to control the temperature, then sets us up in a dimly-lit closed-off back area hidden by a velvet drape. Banks sits on a couch, and Reni takes a seat in a wooden chair next to a modest coffee table.

“I guess you could say I was shy,” Banks says, elaborating on a point from before about his early timidity. “I was very shy.” He laughs. “I was shy as hell. So it was one of those ‘if you know, you know’ type situations. Like, if you know I rap, then you know.” Music was always going to play a huge factor in Banks’ life — his adolescence coincided with New York hip-hop’s golden age, and being that his mother and step-father were young, as a kid, he was listening to Nas, Mobb Deep, and the Wu-Tang Clan as they were first coming out — but the decision to definitively pursue it didn’t come until college entered the equation. He spent a year studying fashion at an institution in Nassau, Long Island, the textile industry being umpteenth on a winding list of career goals he entertained growing up (astronaut, scientist, forensic scientist, fashion designer) while music remained a hobby. As far as higher education, his mother had a Laissez-Faire as-long-as-you-get-your-degree mentality that allowed for just as much autonomy as it did heightened responsibility. By the time his first year started to wind down, Banks had a decision to make. “It wasn’t really like a long process. Just more so like Alright, the semester’s almost up… Am I going back to school next year?,” he says. “And I was like, Nah. I’m actually enjoying just working, and being able to get out of work, go record, not have to worry about waking up early to drive over to Long Island for class.”

When I ask Banks how he sought to lay the foundation for a rap career upon leaving college, the first thing he says is “Thank God for MySpace,” which elicits a knowing chuckle from Reni, followed by a mini-history lesson on how Kid Cudi became one of the first rappers to properly use the internet to his advantage, during which the two are reduced to vehemently nodding heads, Yankees insignias moving up and down, up and down. “MySpace Music was a good platform for people that weren’t signed to be able to upload their music,” Banks narrates, “and also, once we bounced a song out of the MP3, we would email it to Meka [Udoh] over at 2DopeBoyz, in hopes for, like, a blog post or a sharelink.” With the freshly-wound internet of the mid-aughts serving as a homestead for hip-hop’s growing middle ground, the collective grassroots ethos of Banks, Children of the Night, and World’s Fair thrived on using it to eschew the notoriously deaf ears of major record companies, and, as did many in that era, storm the limelight through the back door. “New York was quiet for a while. After G-Unit, the early 2000s, there was really nothing here. If you wasn’t signed to a major [label], you were underground. You had your mainstreams and you had your undergrounds. And around 2010, MySpace Music started to really help people get heard by so and so and x-y-z.”

“People are going to catch onto it one day.”

Banks occupies a certain generational threshold within hip-hop’s lineage, a standing that has allowed him to see such pivotal developments play out both in-person, and on the screen. After he and Reni run me through how the 2011 XXL Freshman cover marked a digital shift in hip-hop, he tells me about how the first time he ever saw or heard Kendrick Lamar, he was doing a show with him. “We were in Cali. We put this little tour together that we called the ‘Tribe Goes West’ tour. It was Children of the Night and Cody. We all put together shows, we all flew ourselves to LA, figured out places to stay, and basically put together a little show run,” he says, Reni chuckling at my visible disbelief. “Yo. Literally. It was these dudes from DC that run Broccoli Fest. Those dudes linked up with this crew in LA called Just Be Cool, and they were like Let’s do this Earth Day show in LA. Just Be Cool was like Alright, we got all of these guys who are the up-and-coming dudes in LA, who are y’all bringing to the table?” Banks, Cody, and the Children of the Night crew were among the East Coast acts that traveled west to perform at the event. “We had just finished soundchecking, and then Kendrick had soundchecked right after us. We had walked outside, and ScHoolboy Q was chilling — he was literally rolling a blunt — and I had bumped him by accident, as he was rolling the weed into his roll-up.” Reni laughs. “Then he looked up at me with a blank stare and I was like Oh shit, my bad, and he was like Nah, you cool, and then he went inside, and I went inside just to listen, and I was like Yo, who the fuck are these dudes? This shit sound crazy! The next day, the show happened, and by the time Kendrick went on — Kendrick was on that lineup, OverDoz, Dom Kennedy, U-N-I, Pac Div… — I was just standing there in amazement. Like Yo, this is fire. This is what we’re trying to do in New York.”

There was also Odd Future: “I saw how Tyler and them grew up,” he starts, “and they were indie. They weren’t signed to nobody. And then their first show in New York, Matt Martians listed me, I went to that show, spoke to everybody afterwards and was like, Yo, this is crazy what y’all doing. They motivated me. Like, We can do this. We can remain who we are, and do this.”

World’s Fair landed their first shows by building relationships with local venues from the ground up, splitting expenses with one another, and building rapport with a cast of underground characters that would eventually unfurl into a bumping, self-made live scene. (“Finding venues, talking to the owners, working out deals… like Alright cool, we’ll pay the bar guarantee if you let us collect all the profit at the door, or alright, we can’t pay the whole bar guarantee, so we’ll split the ticket profit at the door.”) The first venue to seriously open its arms to the collective was the now-defunct Fat Baby, followed by a litany of nightlife hotspots that grew to include Santos Party House, S.O.B’s, and Le Poisson Rouge. At the same time that the event spaces did, the magazines began to take notice, too. “Vice, Noisey, started picking up on what was going on, Fader started picking up on what was going on… and then, fast forward to 2012, shit just really opened up,” Banks says.

Children of the Night released their debut album, Queens… Revisited, that year, followed by World’s Fair LPs Bastards of the Party (2013) and New Lows (2018). The latter project was the product of a collective bout with creative jadedness, after which the group, upon hearing an early version of what would become “Elvis’ Flowers (On My Grave),” rented a house upstate and churned out an album’s worth of material in eight days. The record’s ethos, much like that of Banks himself, is rooted in a sort of animated camaraderie, a narration of New York City exploits that makes you feel like you’re in on it at every crevice, scheming through the highs, and suffering through the pitfalls.

One of the most recent collaborative sonic efforts by World’s Fair is “the function,” a clever bar-for-bar showcase that sees the members, through phone calls, verbose brags, and witty storytelling prowess, plot on attending the titular party over an earworm funk guitar-inflected soul sample. Released on his 2018 LP higher., Banks tells me, with a laid-back smile, that it’s his shit. “Approaching Parsons and Archer, scoop THOTH then we on our way,” group spitter Jeff Donna plots, voice rich with the cadences of gritty 90s boom-bap infused with modern-day swank. “Hillside bound for thee party / that prince been talkin bout for weeks / One of y’all grab the liquor out the trunk / He prolly drunk, Let me call him up since we out front.”

“We can just keep pushing the envelope and making something new.”

The next voice belongs to Prince, and it’s delivered through the grainy diaphragm of a cell phone speaker. “What up drunk!? Is y’all niggas still on the way?” he asks, with attitude. “I been here for about two days, I got two broads I’m a-bout to slay. If I don’t answer my jack, I’ll be in the back, hittin’ two bitches from the back. Bring y’all ass to the back and bring that yac, I’m hanging up, that’s enough of that!”

“That’s literally how it was, too,” Banks says. “Back in that time, that’s how we would all link up to go to a party, or anywhere. We’d be like, Yo, where we going? How we doing this? Phone call, text, Where we linking? What we doing?”

For Banks, “the function” is evocative of World’s Fair’s signature old-school-meets-new-school sound, one that, come the mid 2010s, hip-hop culture gradually began to drift away from. Banks is no stranger to making decisions — whether choosing between school and rap, the underground and the mainstream, or Scarr’s Pizza and Cheeky Sandwiches — and with this one, he relays the choice to me with the same breezy sureness as all the others. “If you weren’t doing trap, or stuff with a certain hi-hat, or with a certain sound, people were turning a deaf ear to it, and that made people start conforming and changing their style,” he says. “And we were like, Nah. We can just keep pushing the envelope and making something new. People are going to catch onto it one day.”