PUNK ROCK’S MIDLIFE CRISIS

Green Day were the first frontmen of an existential crisis punk rock continues to face — and as corny as they were, the genre needed them more than it realized.

SAMUEL HYLAND

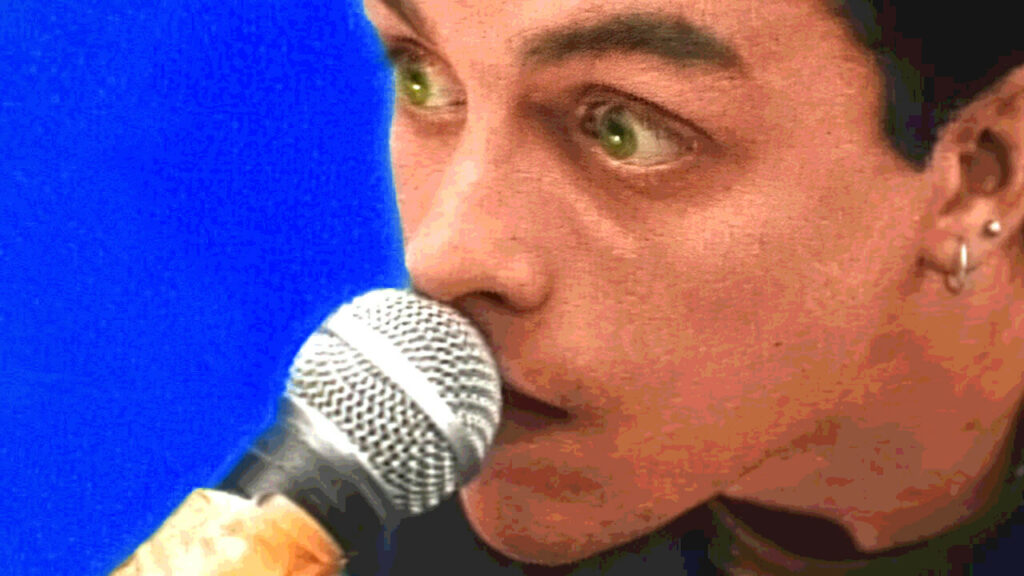

Just about every contemptful unreliable narrator across 20th Century American literature would have despised Billie Joe Armstrong, and Pat Bateman would have gruesomely bludgeoned him to death. I say this in part because in sixth grade, when the same two songs from Green Day’s Dookie and Nas’s Illmatic were the only things in my YouTube watch history for weeks on end, a concert clip I often fixated on was a rousing performance of “Longview” before a raucous crowd of punk Londoners — upon his entrance, Armstrong donned (and, in his defense, quickly tossed away) an achingly corny pair of Halloween-party devil horns. Which, given that Pat Bateman spends his Christmas in American Psycho committing xenophobic stabbings and growing increasingly infuriated with the reindeer antlers ubiquitous at his girlfriend’s holiday party, paves a very broad mental path through which imaginations of a devil horn-clad Armstrong at knifepoint may begin to exist. Armstrong’s hate-ability for America’s favorite literary narcissists stretches beyond just party props, though, and further into the sort of “phony” stature Holden Caulfield despised and Bateman hypocritically exemplified: for the most part, by the time Green Day struck gold with most listeners in 1994, everything about its frontman was shamelessly, and blatantly, fake. He was, in his own words, “an American guy faking an English accent faking an American accent.” He sang about having “no motivation,” when, being a drug addict, dropout, and teenage heartthrob with an electric guitar and a litany of fellow punks at his side, he had just about all the motivation he would have needed to achieve the rock stardom he had quit school to realize. His glammed-out lamentations were punk in the studio, and pop on the charts.

“You have to guess that the teenagers who were latching on to Green Day’s trivial rhetoric knew at some level that it was trite. But given how endemic it proved to be across America’s increasingly-jaded youth, the music functioned to a point where either they didn’t know, or they just didn’t care.”

As much as it was a formula that thrived on backwardness, it was a formula that worked. And it needed to. America’s primitive punk rock soundscape — one forged in white supremacist ties and a gruesome ethos — had, by this point, faded into the measly debris of once-prominent bands whose sons and family friends were now sluggishly playing their futile tours for them. The 1980s gave rise to a materialism that glamified both the sonic and social zeitgeists, effectively washing away the old face of anti-everything rock, and setting new, slightly more sparkly, ground for a younger disillusioned vanguard to occupy. Green Day were the direct inheritors of this construct: their punk gospel wasn’t as much the difference between life and death as it was the difference between child’s play and boredom. Whereas someone like Johnny Rotten was beefing with the government, for instance, Billie Joe Armstrong was beefing with his mom. “She said I was disrespectful and indecent,” he told Rolling Stone’s Chris Mundy of a letter he received from her in a 1995 cover story. “[…] She couldn’t believe that I pulled my pants down and got in a fight onstage.”

“Longview,” the existentially jobless teenage boy’s rallying cry Armstrong recited before that London crowd (in devil horns, of course), lives as an anthemic microcosm of the group’s relatively thumb-twiddling spirit. Over a circular bassline that sounds like something an amateur strummer would stumble upon whilst drunkenly attempting to cover the Beatles’ “Day Tripper,” Armstrong declares in a pubescent, faux-Cockney drawl that he’s “so damn bored,” “going blind,” and “smells like shit.” The entire song hinges on a similar confessional quality, one that fetishizes admission of life having gotten so boring that “masturbation’s lost its fun.” But it’s a confessionalism that’s contagious — at least contagious enough for a sixth grade me to ecstatically send the YouTube link to all my friends, only to be ignored by all but one, who was nice enough to admit that he didn’t make it past the 1 minute-mark because he “didn’t care for it.” You have to guess that the teenagers who were latching on to Green Day’s trivial rhetoric knew at some level that it was trite. But given how endemic it proved to be across America’s increasingly-jaded youth, the music functioned to a point where either they didn’t know, or they just didn’t care. “Adolescent interest may always be piqued by lyrical references to drugs and jerking off, the way a 5-year-old mainly laughs at the Calvin and Hobbes panels where Calvin is naked or calling Hobbes an ‘idiot,’” Pitchfork’s Marc Hogan wrote of the track in a laudatory review of Dookie. “But as beer-raising alt-rock goes, this is also exceptionally bleak, with the narrator’s couch-locked wank session transforming into a self-imposed prison where Armstrong semi-decipherably sings, per the liner notes, ‘You’re fucking breaking.’” In the age of Green Day’s teenage-fever punk palatability, “breaking” looked a lot like being a self-aware-albeit-annoyingly-proud screw-up, sans being gruesomely axed down for it by an enraged Pat Bateman.

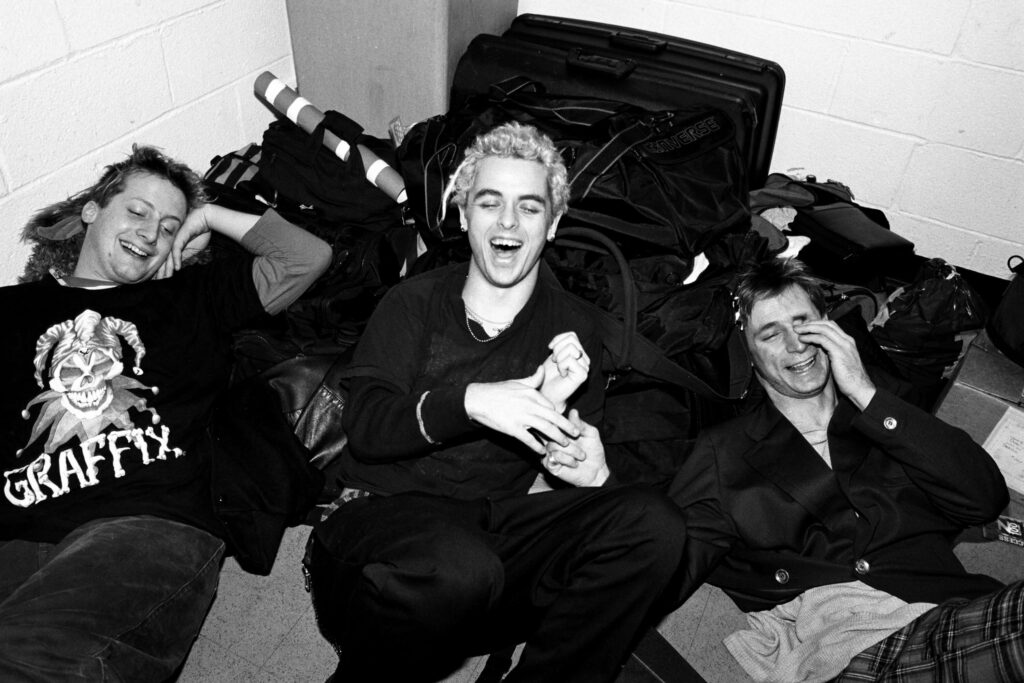

For as much as Billie Joe Armstrong’s rock star ethos is a caricature of the ill-tempered, snobbish brand of faux-punk the 2000s would go on to incubate, his origin story is quite analogous to those of guitar-slinging forefathers who led far more raucous revolutions. When he was a 10 year-old in Oakland, California, his father, a jazz musician, died of esophageal cancer — after which he was replaced by a stepdad neither Armstrong nor his five siblings were very fond of. The new family dynamic spurred a violent tendency in the children, which Armstrong channeled (if you couldn’t guess by now) into a fervent appetite for punk rock music. Upon bonding with schoolmate Michael Pritchard over shared tastes, the pair’s relationship grew rooted in smoking joints and jamming alongside one another, directly prefixing the formation of an amateur band dubbed “Sweet Children.” Which, given the terms of their relationship, they certainly were not: with Armstrong and Pritchard on guitar, leather jacket-toting teen Raj Punjabi manning drums, and Sean Hughes on bass, they changed their name to “Green Day” following a smattering of lineup changes as a nod to their collective fondness of marijuana. (Another significant name change would be Pritchard’s rechristening as Mike “Dirnt” — a reference to the “dirnting” he did on bass guitar upon replacing Hughes.) The band’s longtime (going on a third decade) three-man lineup would be solidified with Punjabi’s replacement on drums by Frank Wright III, who would go on to be known by the moniker Tré Cool.

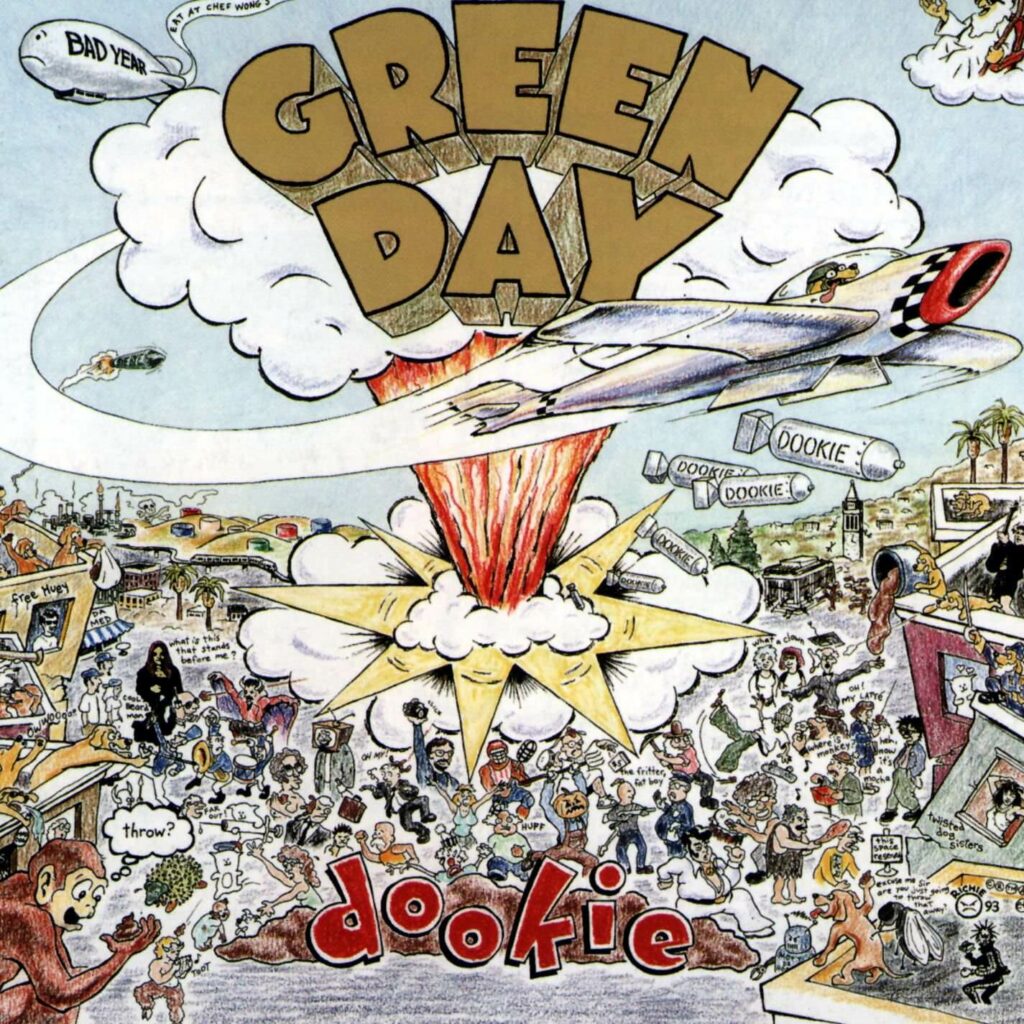

Kerplunk!, the trio’s first semi-polished attempt at a studio debut, arrived in December of 1991, three months after Nirvana’s culture-shifting breakthrough Nevermind had already altered the trajectory of rock music’s foreseeable future. It helps, in retrospect, to look at Green Day’s pop-friendly heartthrob punk in context of Nirvana’s brazen authenticity as a means of discerning the angle through which they infiltrated punk’s lineage — if Nirvana caught on because they gave voice to a population of once-ashamed losers, Green Day did because they made already-confident losers that much more confident. This wouldn’t happen with Kerplunk!, of course, if not for its rough sound then for its stiff competition, but rather with Dookie, the group’s 1994 follow-up. The chaotic appeal of the LP is well encapsulated on its cartoon-laden album cover: in a convoluted Where’s Waldo-esque sketch bustling with caricatures, a monkey wonders whether or not to chuck a piece of shit in his palm, a larger-than-life housefly politely asks a dog whether he’s just going to “throw away” the piece of shit in his palm, and, at the epicenter of a million similarly crappy scenes, a monumental nuke mushrooms into the diarrhea-colored words “GREEN DAY.”

“It’s a construct that allows fans to hitch a ride on a storied lineage, gleefully sticking up tatted middle fingers through the upticks, whilst being able to conveniently hop off whenever the culture loses either its protective bubble, or its relevance.”

The satirical marketing tactic, equally present in the LP’s musical makeup, is one that banks heavily on not taking oneself seriously. Even if Green Day did regard themselves as heirs of hardcore punk rock’s upper echelon, leave their music to speak for itself, and its most potent element was a quasi-Michael Scott quality of somewhat begging to be seen as a friend rather than a superior. “Do you have the time to listen to me whine about everything and nothing all at once?” Armstrong asks in the now-iconic opening lines of “Basket Case,” an autobiographical track about a struggle with anxiety disorder he had actively been passing off as craziness. “I am one of those Melodramatic fools, neurotic to the bone, no doubt about it.” The lyrical content of Dookie is the sort of stuff a pre-teen Yu-Gi-Oh! enthusiast would mutter under their breath whilst shuffling their cards alone in a deserted corner of the lunch table, not the least bit upset at not having friends, but perfectly fine poring over a freshly-dyed mane of hair and eagerly awaiting the day someone asks them what’s playing in their overhead headphones. It functions best as music for outcasts who already think themselves the coolest people on Earth, needing a punk band not to teach them that they matter, but confirm their superiority complex.

“On Dookie, Armstrong channeled a lifetime of songcraft obsession into buzzing, hook-crammed tracks that acted like they didn’t give a shit—fashionably then, but also appealingly for the 12-year-old spirit within us all,” Hogan wrote. “Maybe they worked so well because, on a compositional and emotional level, they were actually gravely serious. Sometimes singing about the serious stuff in your life—desire, anxiety, identity—feels a lot more weightless done against the backdrop of a dogshit-bombarded illustration of your hometown by East Bay punk fixture Richie Bucher.”

Whether Green Day actually didn’t give a shit, or they were just pretending they did it, one way or another, they faked it until they made it. And make it, they did: the first time a 12 year-old me heard of the band, I was at a family gathering, and somewhere behind the 40 year-old bodies snapping photos of my baby cousin, Billie Joe Armstrong, Mike Dirnt, and Tré Cool were on television accepting an induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

🤘 🤘 🤘

One of few lingering traces of Billie Joe Armstrong in mainstream cultural memory remains a childlike outburst he had at the 2012 iHeartRadio Music awards, upon realizing mid-performance that Green Day’s set had been cut in half so that Usher could have more time. He’s obviously drunk, cursing mid-song and growing more explicitly insufferable the more irritated he becomes, until, with a slurred “fuck this shit,” the music abruptly comes to a halt. “I wanna play a fucking new song, fuck this shit,” he sneers, looking back at Tré Cool as the final awkward guitar chord fades. For the remainder of his brazen spiel, Armstrong sounds uncannily similar to an angry SpongeBob Squarepants drunk on Goofy Goobers sundaes after not being promoted: “Gimme a fucking break, one minute left, one minute left. You’re gonna give me fucking one minute? Look at that fuckin’ sign right there. One minute.” Following an increasingly-infuriated series of brash assertions — including “I’m not fucking Justin Bieber, you motherfuckers” — he opts to show the audience what “one fucking minute looks like”: within seconds, both he and Dirnt’s guitars are smashed, and behind a stringent middle finger, the promise is made that “we’ll be back.” The group’s voidness of primitive punk’s hardcore ethos is perhaps most ironically typified by the fact that, seven years later, they would, in fact, be back on the iHeartRadio stage — this time, playing a brief setlist in sparkly suits as corny as Armstrong’s clip-on devil horns.

Just like the band writ large, the moment is a see-through mock-up of a punk generation that, uninvited to grand national television platforms, built their violent legacies from the unforgiving folds of underground club circuits. Several years ago, Ivanka Trump drew mass ire with a just-as-facetious portion of her autobiography in which she asserted that she had once gone through a punk phase. “During my punk phase in the nineties, I was really into Nirvana,” she wrote. “My wardrobe consisted of ripped corduroy jeans and flannel shirts. One day after school, I dyed my hair blue. Mom wasn’t a fan of this decision. She took one look at me and immediately went out to the nearest drugstore to buy a $10 box of Nice’n Easy. That night, she forced me to dye my hair back to blond. The color she picked out was actually three shades lighter than my natural color… and I have never looked back!” Green Day’s aesthetic ethos was entirely packaged for a generation of similarly mid-phase punks, wherein the furthest extent of the culture’s inherent rebellion was dying one’s hair against the wishes of concerned parents. I don’t know why this is what’s coming to my head, but there’s a scene I used to laugh at in the defunct Cartoon Network series Regular Show that sees protagonists Mordecai and Rigby transfixed to a fast-talking advertisement for a punk rock concert — a cartoonishly-gruff voice declares that the band is “ready to rock your 11-15 year-old pants off,” after which the sheepish qualification is made that “that’s our demographic, get over it.” Green Day’s appeal is analogous to the brand of cultural microdosing both Regular Show’s 11-15 year olds, and Ivanka Trump’s hair-dye adventures, shamelessly get their highs off of. It’s a construct that allows fans to hitch a ride on a storied lineage, gleefully sticking up tatted middle fingers through the upticks, whilst being able to conveniently hop off whenever the culture loses either its protective bubble, or its relevance.

The group’s schtick obviously leaves little room for camaraderie with their punk predecessors. “No, you’ve seen imitators, that’s what you’ve seen”, the Sex Pistols’ Johnny Rotten once told an MTV interviewer of Green Day. “And you settled for that, and you think that that’s what it’s all about, Alfie. […] “There ain’t no trashy little love songs in this outfit. Every single lyric is a killing nail in the coffin of what you call the establishment. Like what you work for – MTV? Bye bye. I think I’ve said my piece. Now fuck off!” The basis for the feud is a sterling analogy of the two generations’ ironic interdependence: the bands would have never been beefing had Green Day not just assisted the Sex Pistols on a penny-pinching reunion tour.

“You need a qualification to be punk? Do you have to get a license? Take a test? Pass an exam? Do you have to be born into a punk family? Punk has no particular sound. It has no gatekeepers. It has no box.”

Intra-genre rifts like this one cast the band as frontmen of a larger existential crisis punk rock faced then, and somewhat continues to face now. Green Day drew flak for softening a primitive hardcore steez many hoped would survive, but as of today, a version of this artificial ethos has more or less become the only way to make it. A social media rule of thumb is that publicizing the highlights of a lifestyle will always be more marketable than publicizing its mundane, and sometimes ugly, realities — but not only is the documentation of punk’s ugly reality fading, but perhaps the ugly reality is, too. It’s not difficult to picture the new vanguard of punk rockers slated to take over for Green Day’s generation, realizing that they don’t actually have to spend their Friday nights bloodied in nightclubs to sell rough-edged aesthetics, and earning lengthy award show sets much to the chagrin of a middle finger-flashing Billie Joe Armstrong. If the music is a signifier of anything, the movement has long been in effect: the most successful (disputably) punk rock act of the past five years has been Twenty One Pilots, a hyperpop-adjacent outfit palatable enough to be the first band in music history to see every single song on two albums be certified either gold or platinum. When one Quora user asked why the group was qualified as punk, the top reply epitomized a generation’s worth of breaking down the genre’s rough walls: “You need a qualification to be punk? Do you have to get a license? Take a test? Pass an exam? Do you have to be born into a punk family? Punk has no particular sound. It has no gatekeepers. It has no box.”

It’s the very line of logic that allowed Green Day to infiltrate punk rock’s outcast elitism, and it’s also one that, at some point, will wipe them off of the genre’s zeitgeist. The only way to be punk, perhaps, is to be young — old punk rock bands are doomed to fall short of appeasing a youth disillusioned for different reasons than they were, and, either way, the prospect of gray-haired men performing anti-establishment guitar ballads is too hilarious to mean anything beyond whatever amount of nostalgia sells it. The corny formula Green Day banked on will soon give way to an even cornier formula, pissing off one generation of parents with crumpled Dookie posters locked away in storage, while exhilarating a younger era of high schoolers with hair dye fixtures and bad attitudes.

Yet, when all is said and done, at least for the shit-stained glory days of Dookie, it was Green Day’s turn to be the ill-tempered brats that took on America. Penultimate track “F.O.D” — short for “Fuck off and die” — is as corny and insufferable as their anti-everything caricaturing gets on the LP: midway through the song, after acoustic campfire strums abruptly transition to hyper-distorted power chords, Armstrong’s refrain feels a lot like the internal dialogue of a pre-teen fresh off of being told no by a concerned parent: “You’re just / A fuck / I can’t explain it ’cause I think you suck / I’m taking pride / In telling you to fuck off and die.”

“I blow things out of proportion,” he told Rolling Stone in the aforementioned 1995 cover story. “When you dwell on something for a really long time, that happens. Say you hate somebody, and you sit and think about every single possible way that you could kill them. You’re like ‘I fuckin’ hate ’em, I fuckin’ hate ’em.’ That’s what I like to write about. Blow it out of proportion and then come back to it later and think, ‘That’s kind of silly.’ It’s a good way to get over it fast.”

Whether corny, devil horn clip-on-clad, blatantly artificial or not, Green Day got their kick out of blowing existential loserdom out of proportion. And because they did, whether we like it or not, another generation will get to put its own existential loserdom on the radio as well — if not that, at least they’ll have something to soundtrack memories of foiled hair dye schemes and bad report cards. The only thing likely to stop the band’s cultural cache besides age is a knife-wielding Pat Bateman, foaming at the mouth with rage about clip-on devil horns he catches Armstrong donning in concert. And that’s only if he doesn’t toss them off in time.