Nas’s Brand-New Sonic Mission

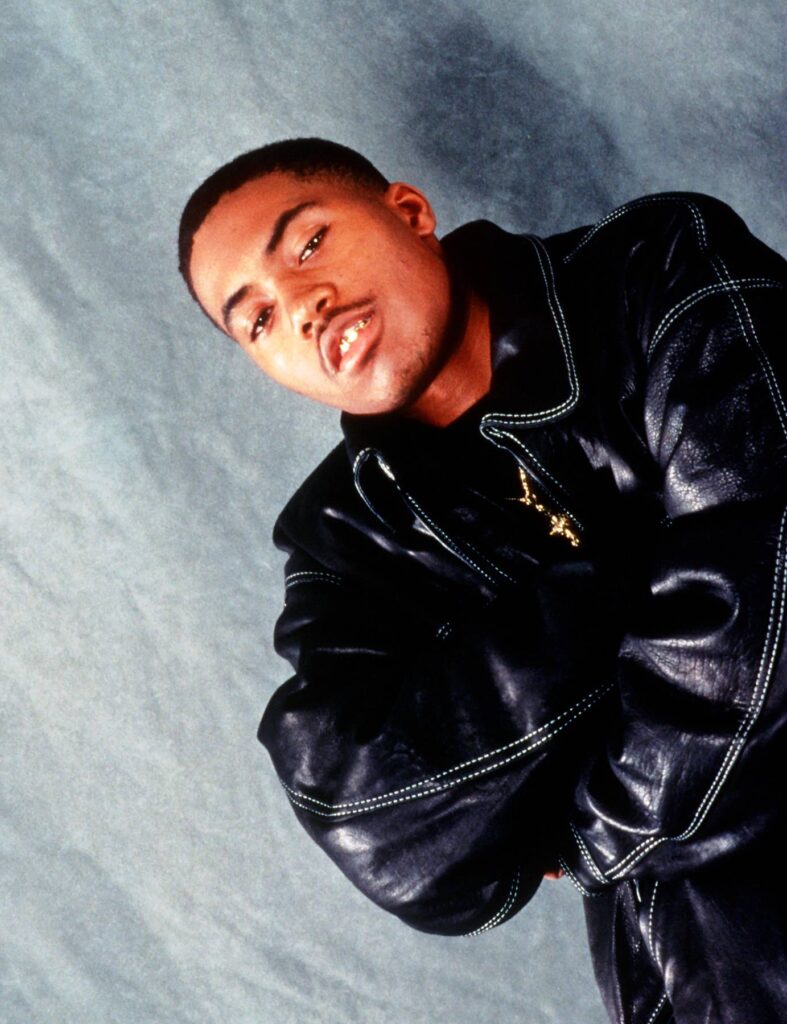

Decades removed from his mythic ascent through New York’s tough hip-hop pantheon — from student, to superstar, to spokesperson — one gets the sense that Nas has graduated from telling New York’s story, to using the platform such roots have granted him to gloat from the throne. (PHOTO: Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

SAMUEL HYLAND

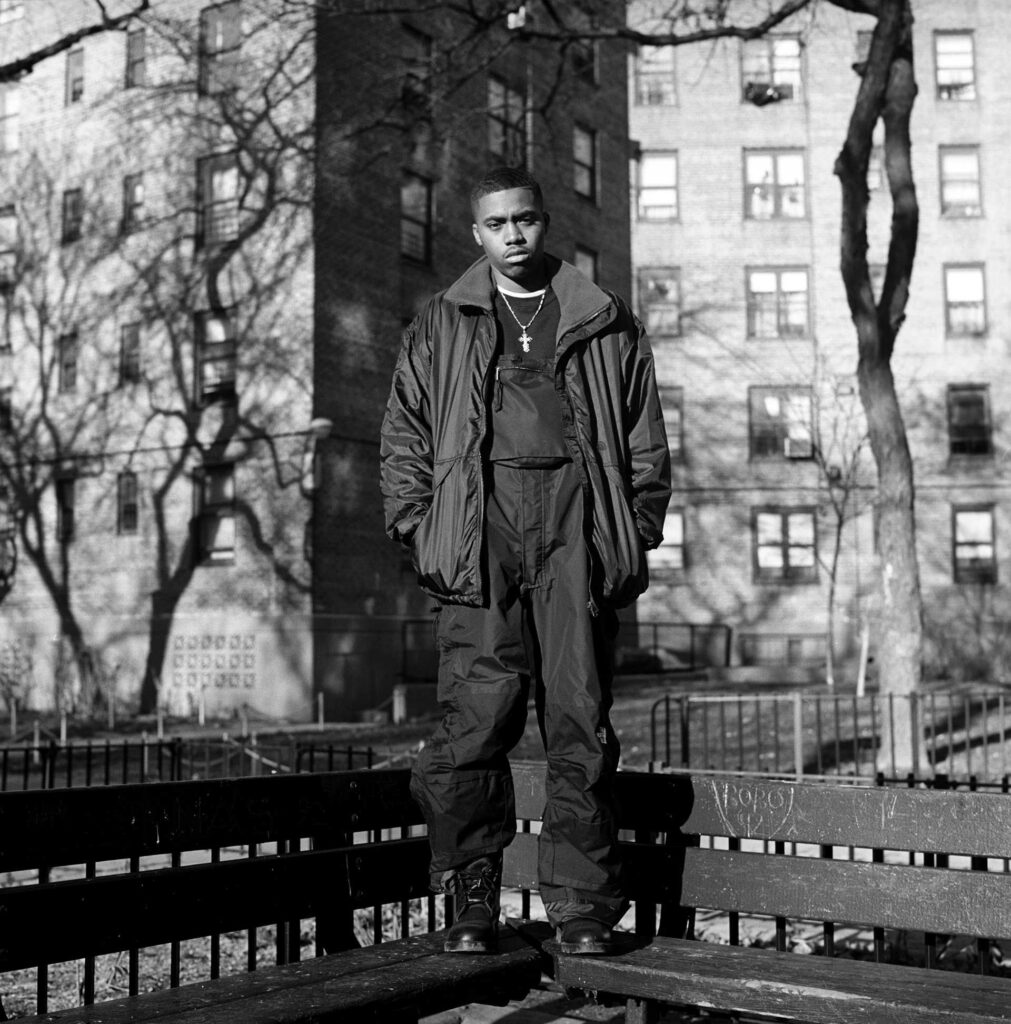

One of the most poignant moments in Nas’s 2014 documentary Time Is Illmatic comes when the rapper, seated beside a longtime Queensbridge confidant, is shown a printed photograph of several beatific characters posing with him on the day of his debut album’s cover shoot. The instance depicted had been a rare beacon of hope for residents of a housing project long revered for its troubled history; every grinning face bore with it not only resistance against a wretched narrative, but anticipation of a beautiful reversal of the construct. It is in no more than thirty seconds that we are shown how bleak this future actually turned out to be: one by one, Nas’s companion points at every last individual in the photograph—the youngest being an innocuous five year-old boy—and rails off each of their grim fates: life sentences, murders, overdoses, et cetera. (The five year-old boy is spending the rest of his life in prison for a gang-affiliated murder he would go on to commit as a young adult.) “It’s so fucked up, just to see what happened,” Nas comments with a gravelly, funereal inflection. He gestures towards his crouching image in the photo. “It makes me really realize: if it wasn’t for music, you would have told a story about that kid, too.”

“Now, between having reached a point where he could finally occupy his cathedra, and having to lug his legend up into the internet era, he’s justifiably content with defending his throne just for the sake of defending it.”

Nas has a certain trademark chill, well embodied by this gravelly, funereal inflection, that in some way complicates his gritty Queensbridge origin story. Decades removed from the youth immortalized on his earliest album covers, Nas’s cadence registers a lot like that of an elderly convict on the discontinued A&E series Beyond Scared Straight, who, with a silent-albeit-morbid monologue on the harsh realities of prison life, quickly renders a group of teenage mischief-makers completely silent and anxious to hug their mothers. One of the most vital add-ons to Nas’s mythology is that both ends of such a human spectrum can, and very much do, coexist: the chill does not cancel out the violent genesis that created it, nor does the violent genesis cancel out the chill timbre that survived to tell its story. It takes little more than a clip from Time is Illmatic, or a deep cut from its namesake LP, to understand that Nas is, before anything else, a survivor — whether the menace be shootings, the murders of his best friends, or the police-riddled New York crack epidemic of the 1980s. (If you aren’t yet convinced of the dark side underneath the calm, at least take his childhood babysitter’s word for it: when I met her in Nashville, she recounted to me that he was a very bad child who earned frequent whoopings.)

Nas’s origin story lacks little in the sort of quintessential, somewhat-deifying mythos borne by similar torch-bearers for an entire people. There’s an eerily-Baldwinian undertone, for instance, to the religious soul-searching that preceded his long-term cultural influence — before he ever started rapping, he sought to kindle an African priviness via the Five Percent Group, an Islam-influenced Black Nationalist Movement, and the Nuwaubian Nation, an American new religious movement founded by Dwight York. (Also known as the exact sort of religious background a long-imprisoned wise old man on Beyond Scared Straight would boast after long years spent in the slammer.) The Black Nationalist spiritualism would go on to be a persistent motif both within his music and beyond it; aside from his name translating to “helper and protector” in Arabic, he dons the Mask of Tutankhamun on the cover of I Am…, and, just one release later, makes use of yet another album’s artwork, title, and lead single to declare himself “Nastradamus.” His religious ethos was curated to be inextricably linked to the streets — a construct made most easily visible by his 2004 double LP Street’s Disciple — which, by some measure, implicitly casted him as New York hip-hop’s spiritual prophet-slash-messiah in a way that big-name counterparts like Jay-Z and Rakim could not have been. Nas wasn’t the type to go on national television and declare himself the undisputed spokesperson of his stomping grounds. Everything with him, much like the very voice reciting the rhymes, was instead marked with a quiet, humble potence: the voids he chose not to explicitly fill spoke just as loudly as the ones he did, and even where there wasn’t solid matter to bear, there was often more than enough mystique to color in the gaps.

But decades removed from his mythic ascent through New York’s tough hip-hop pantheon — from student, to superstar, to spokesperson — one gets the sense that Nas has graduated from telling New York’s story, to using the platform such roots have granted him to lament, or perhaps gloat, from the throne. Which, though completely justified, begs a question of how much of his trademark cultural torch-bearing was a product of its time, and how much of it was his own vision to begin with. The 1980s from which Nas emerged as an MC were marked by various competing intra-city regional narratives. MC Shan’s “The Bridge,” the iteration that directly mobilized Nas’s hip-hop career, was a braggadociously rhythmic crowning of Queensbridge as the birthplace of the genre, setting off the sort of neighborhood-centric pride wherein rap movements were broadly beginning to find their roots. (Its most iconic lines, “You love to hear the story, again and again / Of how it all got started way back when,” were sampled by Nas in a track on his 2012 LP Life Is Good.) “The pride was crazy,” one of Nas’ longtime confidants says in the Time is Illmatic documentary. “We (the Queensbridge housing projects) had an anthem. It was on the radio. People knew, Yeah, I’m from Queensbridge.”

Today’s ethos, alternatively, is less about putting on for your city, and more about leveraging the city to put on for yourself. The internet made this construct the outright reversal it exists as today by flattening the global plane, to an extent that made it more important to craft one’s story in general, rather than excavate, and subsequently dedicate, one’s story from and to the locus that molded it. When, for instance, Playboi Carti, Atlanta born-and-bred, famously made a career-altering trip to the A$AP Mob’s New York City to become the collective’s protégé, it wasn’t like there was suddenly an unignorable complication of his legend — his native Atlanta now arguably owes more to him than he does to it, and it is a dynamic not despised by the home crowd, but enthusiastically leaned into along with the rest of the world. Nas seems to be trying to hitch a ride on the same 21st Century conveyor belt, albeit the muddling factor with him is that he’s become so inextricable from telling New York’s stories that, even if he’s doing it extremely well (and winning Grammys along the way), anything but a testimonial to his stomping grounds cannot help but feel somewhat misplaced. Music consumerism in our age values characteral triumphs over regional ones. It’s ostensible that Nas is trying to cash in on this new wave with an equally-new ethos, rebranding himself as “King” for a series of LPs and opting to rap from the mountaintop rather than immortalize the bottom of the lobster bucket. But it’s difficult to tell whether in 50 years, this move will be looked back on as a continuation of his 90s-born legend, or an awkward alter-ego to be held at arm’s length from who he was when he first took center-stage. As much as he has very much adapted to the present, his past remains very much in charge of how far he has left to go.

“He seems to be doing everything possible to make himself a player in the rap game’s current iteration, yet still, when you think of Nas, you probably think of straight-faced young men superimposed over blurry shots of Queensbridge in the 1990s, before you think of a bespectacled middle-aged man donning early-stages dreadlocks en route to accept his largest career milestone.”

Nas released Magic, his 15th studio album to date, this past Christmas Eve. One of its most striking facets is the notion that as his mission has shifted, so has the voice tasked with carrying it out — now, rather than the chill, quasi-Beyond Scared Straight intonation he eased his way up rap’s regional ladder with, given that the impetus is now strictly personal aggrandizement, he finds himself several noticeable notches higher on the aggression scale. On a track like “Meet Joe Black,” he comes out firing in a manner not too far removed from J. Cole on most of The Off-Season, shout-rapping through a series of verbose claims to supremacy and insults to unknown adversaries. “Your top three, I’m not number one, how could you post that?” he argues in the track’s chorus. “I wear the crown, the city is mine, you cannot hold that / I’m not the one to go at, you fuck around, meet Joe Black” (Joe Black being death, as personified in a 1998 film of the same name). The most memorable, if not the only, time in his career that Nas was ever this sonically enraged was when he was either beefing with someone, or speaking to political issues — namely, his fabled Jay-Z feud and the at first controversially-named Untitled LP he would release in response to racial tensions in 2008 — but the difference in cases like these was that there had been, whether in the form of an antagonizing rapper or an antagonizing system, a discernible threat to the throne he had built a career carving for himself. Now, between having reached a point where he could finally occupy his cathedra, and having to lug his legend up into the internet era, he’s justifiably content with defending his throne just for the sake of defending it: much like the “Meet Joe Black” verse, neither a clear rival nor home turf must be defined for an empire to be enforced.

🎷 🎷 🎷

Perhaps the most notable selling point of Magic for Nas’ younger listeners was an A$AP Rocky feature, tucked seven tracks deep in an overtly 90s-core — record scratches, choppy sampling, DJ Premiere twisting turntables contemplatively in front of an open upper-floor window in the music video, etc — exercise in empty nostalgia-baiting. Though Nas and A$AP Rocky hold spaces in the same New York hip-hop lineage, putting the two in conversation with one another arguably serves to make their generational divide that much more glaringly obvious: Nas can never occupy the swagged-out, 21st Century I-just-got-Rihanna-pregnant strain of artistry A$AP Rocky champions, nor can A$AP Rocky emulate Nas’ deeply-spiritualized, revolutionary regional auteurship, and hearing them each actively fall short of the other’s pedestal in real time subtly raises the question of whether this bespoke lineage still exists at all. The track’s music video is a fitting embodiment of its muddy ethos — while A$AP Rocky can’t decide whether he wants to leave his house as a family man, lament across town as a suit-and-tie city slicker, or trade his lavish babushkas for homeless rags, Nas, too, isn’t anywhere near a decision on whether he wants to cosplay A$AP Ferg on the cover of Floor Seats, cryptically glare behind black aviator shades, or lament across town as a trenchcoat-clad undercover cop.

Perceptibly, what made the New York hip-hop 90s different, and also clouds the stringent regional narrative its era produced in context of today, is the lack of an online apparatus to make the movement an immediate landmark rather than a slow-burning generational storyline. Both Nas’ Illmatic, MC Shan’s “The Bridge,” and the hundreds of other rap records that populated New York’s initial claim to sonic fame, purported themselves more as chapters in a lengthier saga than one-offs intent on obsoleting what had already been established. Compare that to the mission of a group like the A$AP Mob, and what would become the future of New York regionalism is bluntly put into perspective: “(A$AP) Yams and I used to sit up at night on the phone, strategizing how we would single-handedly come in and take over this rap shit, on some young shit,” A$AP Rocky said in a Noisey documentary released the same year as Time is Illmatic. “We knew we didn’t want to be under nobody. We didn’t want to be nobody’s protégé. We didn’t need no co-sign. We said we gon’ come in this shit our way, and (…) hold it down on some A$AP shit.”

In an era where the A$AP Mob is far from the only upstart (okay, maybe not “upstart”… or “up” at all… in their case) act seeking to tear down old constructs and plant new long-term flags in the debris, what Nas must figure out is how he’ll leverage his past — or not — en route to a future beyond the trappings of nostalgia. He is, very much so, the epitome of “old constructs” in not just New York rap, but rap in general. His resumé is, even though his sole career Grammy came just last year, far more staked in pre-2010 than post. He seems to be doing everything possible to make himself a player in the rap game’s current iteration, yet still, when you think of Nas, you probably think of straight-faced young men superimposed over blurry shots of Queensbridge in the 1990s, before you think of a bespectacled middle-aged man donning early-stages dreadlocks en route to accept his largest career milestone. The only way for hip-hop’s lineage to work, it seems, is for the forefathers to stay with the forefathers, and the young troublemakers to stay with the young troublemakers. It’s the reason why an A$AP Rocky feature on a Nas track sounds like a big-bodied uncle hunched over at the kiddie table at Thanksgiving dinner: hip-hop is structured so that we cannot imagine the mainstays beyond where we first met them.

“Survivor’s guilt is interesting,” Nas told i-D following the release of King’s Disease II. “The longer you stay around, the more of a target you become. That’s the danger of staying around. You don’t want to be the one hit wonder, you don’t want to have a short career, but if you do have a long career, then you are a target for so many people.” Perhaps another complicating factor in Nas’ inter-generational breadth is that this response was not in reference to upstart hip-hop acts hungry to claim his throne, but the murder of Tupac shortly before, upon squashing their beef, the two were supposed to join forces with Suge Knight to establish an East Coast branch of Death Row Records. Nas’ mythos was born out of a hip-hop culture that often had real-world life and death implications, in a way that, although such ultimatums remain permanently entangled with the infrastructure, is not quite as unavoidable in an era where most dealings are done online. It is in this way, conceivably, that the risks are much cheaper today than they were in the past. Everything about Nas is high-stakes — from his ethos, to his mission, to his survival — whereas most everything about his 21st Century colleagues wanes several notches less urgent. If we focus on just the regionalism that first put Nas on a pedestal, most of the instances wherein locational identities play roles in modern rap culture are doomed to someday be punchlines, regardless of whether they are serious in nature — the last time any of us talked about Drake being from Canada, or 21 Savage being born British, it likely wasn’t about putting on for one’s streets.

“It’s too dark to see tomorrow — no matter how much of his throne is layered with prophetic spiritualism — and a new young inheritor is being sought after by the fabled black cloud as we speak.”

The hip-hop universe is one where either being murdered or falling off is far more common than living to win Grammys at 50 years old, so to make it to the level that Nas has is legacy-cementing in and of itself. But even more so, much like what curses were inherited by those who first played cultural torch-bearing roles before him and before hip-hop, new autonomy also means new existential questions. Every artist that lives (both literally and artistically) beyond the version of themself that consumers remember is inherently faced with young fan-bases to attract, old fan-bases to keep entertained, and a likely-outdated philosophy to publicly make sense of for an entirely new framework. In the case of someone like Mariah Carey, for instance, transitioning into veteran stature looked like being pigeonholed into a one-size-fits-all diva archetype — exacerbated by nationally-televised bouts with Nicki Minaj, embarrassing live show butcherings, and tabloid stories taken and run with by an increasingly gossip-hungry public — to the point where she had to publish an autobiography, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, only for unwanted narratives to remain relatively inescapable. In perhaps the most infamous of post-pinnacle pathways, because Michael Jackson lost more and more control over his public image as he grew older, his final iteration was as a plastic surgery-overtaken, publicly troubled caricature, loved by celebrity chitchat magazines, and hated by many of the consumers who once adored him.

It’s difficult to say whether Nas’s story will wind up being much different. For one, again, he’s low-key to the point where he’s far more likely to talk sense into a group of at-risk teenagers on a canceled A&E series, than he is to address the American public with a detailed memoir. But then again, not only is he up against an era that moves much faster than he does, but also one that takes things a lot less seriously than he ever will. One of the most striking moments in “The World is Yours,” the sparkling Illmatic single that introduced many to his myth, sees him follow up a lament about having “no crew to keep [his] crown or throne” with matter-of-fact assessment of his predicament: “I need a new nigga,” he declares, “for this black cloud to follow, ‘Cause while it’s over me, it’s too dark to see tomorrow.” Though Nas was 20 years old at that point, the “new nigga” for a hip-hop gospel that didn’t know it needed reawakening, he finds himself in the same spot nearly three decades later. It’s too dark to see tomorrow — no matter how much of his throne is layered with prophetic spiritualism — and a new young inheritor is being sought after by the fabled black cloud as we speak.

In a closing scene of Time is Illmatic, Nas is stopped in Queensbridge by a scrawny young child, no older than the aforementioned 5 year-old currently serving a life sentence, who reveals that his middle name is Nasir. “Now look,” he says after giving the child a hearty high-five. “Everybody with that name are kings. We are kings, okay? Just know that for the rest of your life. Don’t ever think anything else — just know that you’re a king.”

No matter where he winds up carrying his legacy, it is morbidly likely that, had it not been for Nas, if you pointed to that kid on a postcard twenty years from now, the story being told would be quite different — one with little to do with royalty.