Hot Rats, Teletubbies, & the Strange Benefits of Multifaceted Consumption

Consumed in conjunction with the chilling paranormality of Albert Camus’ hyper-realistic 20th Century novella, Frank Zappa’s music is not taken fully in the elation it seeks to conjure, but rather as an intensifier of an already-unsettling literary experience that summons dismal demons of its own.

SAMUEL HYLAND

Albert Camus’ The Stranger is an ominously written, concise novella about – at least as far as I’ve managed to get up to – the haunting monotony surrounding one man’s deceased mother. Although I first got my copy of it over a year ago as a bright-eyed second-time high school intern at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, I have not made it past the second chapter. This was very likely because I lost track of time. That version of me existed, of course, in a pre-COVID world: I would go to school for seven hours, participate in extracurricular activities for up to three hours, spend about two more hours returning home via NYC Subway and Long Island Railroad, arrive home late in the evening, do homework through the wee hours of the morning, and taste my first ounce of free time at about 3 AM. It had only been about two hours – 5 AM – past that cutoff, when I first decided that I would wake up early to open The Stranger on my first day of the impromptu vacation forged by Regents exam week.

The architecture lamp that I had received that past Christmas as a gimmick to make me feel more professional did just that on my childhood desk, catapulting an intense white light into an upper corner of my bedroom. My clothes for the following week’s orientation at the Met Museum were hung up, nicely ironed, on my spinning chair: An off-brand striped blue rugby shirt from Amazon, a pair of loose gray khakis (also shamelessly purchased via Amazon. What? You know Amazon was your closest companion when you were preparing for your first internship), and an equally off-brand navy blue chore coat ordered from (you guessed it) Amazon in a regrettable Instagram-influencer-inspired online shopping splurge, which for some reason often got unusually – excessively – wrinkly for a winter jacket. I read The Stranger for about forty-five minutes that morning, which was about as long as I could continue to believe the lie that I was capable of waking up for the day before I could see the sun through my window. I opened my eyes to four missed calls from my mother, an orange glow where the sun was supposed to be, a text from my father saying that he would be home from work soon, sweaty blankets, tumultuous hair, and a book held open to its fifth page by my thumb.

“The converse of the matter is an oft-overlooked element of what makes the typical student gravitate towards (seemingly) counterintuitive multi-tasking in the first place: what if we could know everything?“But now, to the present. Unlike then, much like everybody else, I am – whether I like it or not (I like it) – indefinitely homebound. This past Saturday, I had an interview subject opt to reschedule at the last minute. It had always been my intention to revisit The Stranger. Today, I had time. Suddenly inspired, I shut down the Zoom application, threw my laptop shut, returned the things I had rearranged for sake of on-camera professionalism to their rightful places in my room, and hopped onto my bed. I grabbed the novella from my headboard. I fell right asleep.

Now, luckily, another difference between this past Saturday and that January morning in 2020 is that I had a considerable bit more control over my innate gravitation toward undeserved naptimes. Now, instead of opening my eyes sometime in the distant future, I reluctantly crawled out of my bed around 5 pm. I waddled to the kitchen. I gobbled down three yogurts – all of which were supposed to be turned into a smoothie until I learned that we had run out of bananas. When my mother urged me to spend a few hours in the living room with the family, I watched the Brooklyn Nets outplay the Golden State Warriors until I was bored enough to fully wake myself up.

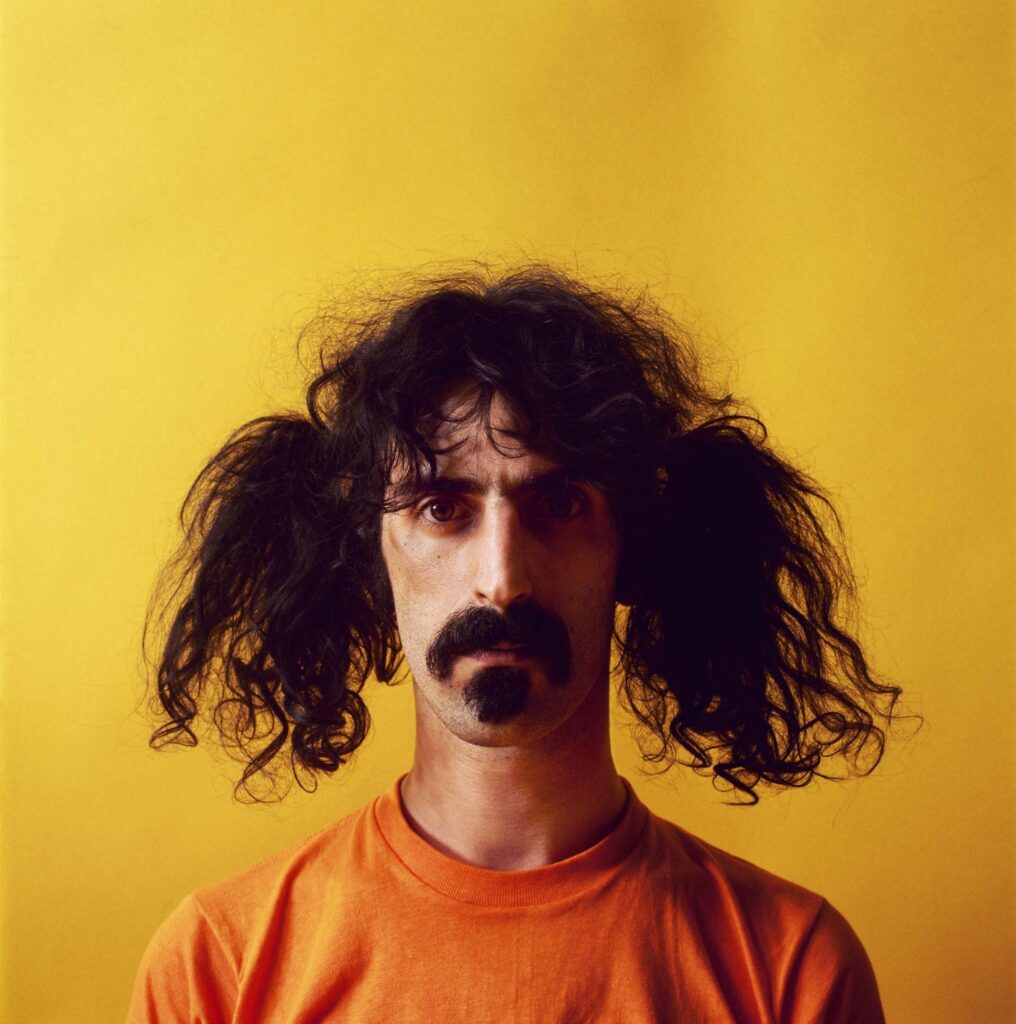

At about 11 pm, though, when the game was over, and I was all of a sudden responsible for as many hours of free time as I would have spent writing if the interview went as scheduled, the first thing my eyes attached themselves to upon re-entering my room was the semi-lofty stack of forlorn vinyl records I had ordered (guess where) for my eighteenth birthday. In several weeks, I had only listened to one – The Velvet Underground & Nico – out of a lengthy list of titles that included David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, The Velvet Underground’s Loaded, and Frank Zappa’s Hot Rats.

Then it struck me: I was going to read The Stranger today, wasn’t I? I asked myself. Why not kill two birds with one stone? I reached beneath the brand-new portable record player I had been gifted by my parents not too long prior, and extracted the Zappa album from the pile. All the Zappa I had heard up to then had been winding, strange, eclectic. I had only ever seen the novella described within that umbrella. What could go wrong with consuming both at the same time?

In retrospect, many things. But in a sense, things went so wrong that night that they somehow, in a really weird way, went right. Before we even address the book in itself, I feel that it ought to be talked about, the ritualistic, eerie, sacreligious aura given off by playing Frank Zappa – on vinyl, for that matter – behind the closed door of your bedroom at midnight. Frank Zappa’s music is not frightening up-front: it is eerie in the sense that it exists outside of time. The general connotation derived from statements that Zappa was “ahead of his generation” – which, yes, he very much was – serves only to address the notion that he innovated beyond what his era may have collectively suggested he would. But, rather, Frank Zappa did not exist only in front of the clock; he lived above, below, before, behind, around it. I often quip to my twin sister about the strange sense of being permanently stuck in a moment in time, perhaps a fever dream, given off by the daytime toddler TV program Teletubbies. Much like Teletubbies, Frank Zappa’s music is jovial, inviting, and conceptually opposite of ominous – but one cannot help but get the impression that they are in a room of mirrors, out of which once any exit is made, an entire carnival of everlasting juvenile purgatory awaits.

“Of course, this is not nearly as decisive a factor as the aforementioned urge to ease surrounding monotony. But the caveat of Kevin’s father, once measured in the situational context of art minus the homework, quickly becomes one further rooted in inhibition of mental productivity than invigoration of it. “I knew I was in trouble the moment my experiment commenced. The first paragraph of The Stranger is a monotonously delivered, oft-cited stream of consciousness about events surrounding the death of the protagonist’s mother.

“Maman died today,” the famed opening line reads. “Or yesterday maybe, I don’t know. I got a telegram from the home: ‘Mother deceased. Funeral tomorrow. Faithfully yours.’ That doesn’t mean anything. Maybe it was yesterday.”

Conversely, blasting through my record player’s speakers at the same time that I read these exact words was Hot Rats’ opening track Peaches En Regalia. In short, Peaches En Regalia is upbeat. Very upbeat. I was reading a blandly recounted, unsettling, sacred recollection of familial death. I was listening to a brass-suffused, royal entrance-esque, jazz fusion jam session that seemed to grow more exponentially jocund with each full revolution of the disc: piano, then horns, then octave bass, then organ, then saxophone, then clarinet, then some other percussion instrument I couldn’t discern behind tightly congested layer after tightly congested layer of euphoria – every time I wanted to allow myself to feel sympathy for the narrator, any ounce of secondhand mourning I felt was undone by musicianship that told me to drop all my worries and be free. Once again: it was past twelve o’clock in the morning.

If I had not already been weirded out by my decision, reading onward in The Stranger only solidified both my apprehensions, and my now-reawakened childhood fears alike. Much like he did in the opening spiel, Camus’ narrator did not allow much room for literary expansion beyond the blunt facts of whatever it was that he had to say to tell the story. In the pages that ensued the first, he wrote of getting on a bus to the home his mother stayed at throughout the final years of her life. He retold the events with the succinctness of a disgruntled hard news reporter unwillingly stuck with his job: He gets to the home. He is greeted by the caretaker. He wants to speak to the director. The director is unavailable. He is taken to the mortuary.

Yet, as drearily as the tale was presented, it was at this point specifically – in the mortuary – that I wrapped the covers around myself extra tightly (this was not the most pleasant thing when I was reminded that I actually had to get up to flip the record over to Side B). First off, there was the naked concept of being essentially alone in a brightly lit room inhabited by only you, your mother’s casket, and a talkative 64-year-old man standing at your back, whispering in your ear with his hand fixed onto your shoulder. Then, the borderline supernatural only-in-the-movies shit: “At that point the caretaker said to me, ‘She’s got an abscess,’” the narrator wrote. “I didn’t understand, so I looked over at the nurse and saw that she had a bandage wrapped around her head just below the eyes. Where her nose should have been, the bandage was flat.”

But – yes! – our friendly main character must not have been all by himself for his mother’s homegoing service; how inhumane would that have been? Of course, there had to be some form of humanity – the idea of it, at least – to keep him company over such a rough patch:

“That’s when Maman’s friends came in. There were about ten in all, and they Boated into the blinding light without a sound. They sat down without a single chair creaking. I saw them more clearly than I had ever seen anyone, and not one detail of their faces or their clothes escaped me. But I couldn’t hear them, and it was hard for me to believe they really existed.”

Some time later, moreso, our good friend Monsieur Meursault bore spectacle to the gradual filing in of more elderly tenants, predicated by an offputtingly ritualistic seating arrangement:

“What struck me most about their faces was that I couldn’t see their eyes, just a faint glimmer in a nest of wrinkles. When they’d sat down, most of them looked at me and nodded awkwardly, their lips sucked in by their toothless mouths, so that I couldn’t tell if they were greeting me or if it was just a nervous tic. I think they were greeting me. It was then that I realized they were all sitting across from me, nodding their heads, grouped around the caretaker. For a second I had the ridiculous feeling that they were there to judge me.”

So, now, I had to forget about the fears of solitude and death. It wasn’t just being alone in a room with your dead mother and an annoying 64-year-old man: there was suddenly mental space to be shared with noseless nurses, ghostly old people, the sensation of being scrutinized by those ghostly old people . . . and of course, emanant purgatorially eerie Frank Zappa music for good measure.

“I read The Stranger. I listened to Hot Rats. It was one of the single most horrifying moments of my life. But – for as many such combinations exist – that particular class of eerie dread can never be conjured by any other pairing.”

For the majority of the time I spent haunted by the mortuary scene, Willie the Pimp, the second track on Hot Rats, was the song that was playing. This is where one can make the argument that Frank Zappa’s music exists outside of time. The song Willie the Pimp, in itself, is over nine minutes long. In its opening minute – encasing some of the only vocals sung by Zappa throughout the whole record – the famously weird guitar-slinger sneers his way through the role of the titular hustler, boasting about girls he has at his disposal; setting up a latter-related rendezvous; rubbing his lifestyle in the collective face of those who leech off of it for temporary sexual pleasure. By the second minute, the jazz ensemble has taken over much of the song, and longtime Zappa associate Captain Beefheart can be heard screaming crazed idiosyncrasies. Hot meat! Hot rats! Hot chicks! Hot zits! Hot wrists! Hot ritz! Hot roots! Hot soots! A minutes-long improvisational electric guitar solo fills out the remainder of the track. The famed ‘wah’ pedal – a guitar effect that, in itself, embodies the circular principles of limitless time with each stomp – soon embraces its role as chief teletubby-effect bearer. Once again, consumed in conjunction with the chilling paranormality of Camus’ hyper-realistic 20th Century novella, Zappa’s music is not taken fully in the elation it seeks to conjure, but rather as an intensifier of an already-unsettling literary experience that summons dismal demons of its own. At what point does the insanity – if it is even ever meant to – come to a screeching halt?

My post-midnight plight serves to raise a question about not only dual reading and listening, but ideas around art consumption writ large. When I was young, I often found myself scolded by whoever happened to be watching me at the time – be it my parents, my grandmother, or the quick-tempered semi-old lady who ran a caretaking-slash-homework help service down the block from my elementary school – for listening to music at the same time that I completed my homework. Years down the line, I managed to strike up a compromise with my dad that made the no-music-during-homework-time rule only apply to writing-based assignments. Yet, even up to present, I continue to feel the widely noted allure of utilizing music not as a means of sensory pleasure, but as a mental stimulant, amidst the most monotonous work hours of the typical day.

Many share such an inclination. In an introduction to one study published by The Conversation, an eleventh grade student by the name of Kevin posed: “I am in year 11 and I like to listen to music when I am studying, but my dad says that my brain is spending only half of its time studying and the other half is distracted by listening.” He continued, further delving into his father’s rhetoric: “He says it is better to leave my phone out of my room and concentrate on studying rather than listening to music. Is it OK to listen to songs when I am studying?”

Per a 2018 analysis, a majority of teenagers appear to share Kevin’s very predicament: in a survey of 80 students, Cedar Falls High School reports, 94.4 percent said that they listen to music while doing homework, and 83.3 percent said that they think music benefits them while studying.

Such vast numbers, I learned from my Zappa-slash-Camus crossover experience, can be very distinctly attributed to the natural gravitation of the human mind to consume as much as it can possibly consume before time runs out. Fear of the dark, I read in an article some time ago, stems from the sudden confrontation of the brain with everything that could conceivably exist without its knowledge – it is not necessarily the fear of darkness itself, but the terror of what unknown entities lurk within it, that drives any human mind into hysteria. The converse of the matter is an oft-overlooked element of what makes the typical student gravitate towards (seemingly) counterintuitive multi-tasking in the first place: what if we could know everything?

Of course, this is not nearly as decisive a factor as the aforementioned urge to ease surrounding monotony. But the caveat of Kevin’s father, once measured in the situational context of art minus the homework, quickly becomes one further rooted in inhibition of mental productivity than invigoration of it.

Starting with physical art, for reference, the longstanding institution of museums and adjacent galleries have trained the mind to consume one work of art at a time. We start with one painting. We glare at it, until it either means something to us or gets boring. We may whip out a sketchbook depending on the situation. We move on to the next once the ritual is up.

In my first stint with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, albeit, I was fortunate enough to have been hired around the same time that its Play it Loud: Instruments of Rock n’ Roll exhibit – a temporary establishment at the museum dedicated to an artifact-centered trek through the history of contemporary music – opened its gates to the public. The very first time I strolled through it, by myself, before work hours, was religiously salubrious enough for me to realize on the spot that art was not limited to gawking at framed ancient imagery on white walls and waiting for it to do magic tricks. At that point, I was desperately obsessed with the concept of becoming a world-famous teenage fiction author by day, and all-around-prodigy by night (which, obviously, did not work out as planned). With a copy of Stephen King’s On Writing that my sophomore English teacher gifted me to assist with such a goal, I made the decision on a whim to read as much as I could over my daily Central Park sit-downs while at the same time listening to randomized albums suggested to me by Spotify. I did not make as much progress in King’s book as I would have without music; nonetheless, the music made everything my eyes touched twenty times more vivid: Pete Shelley’s howl made the author’s high school newspaper adventures appear to be lovelorn faux-tragedies, Earl Sweatshirt’s murmur made the comparison of literary skillsets to work toolkits register as a life-or-death jot-it-or-not ticking time bomb, and the MC5’s power-chord-propelled cries of I want you right now made me more sure than I had ever been of an ambitious career that would soon prove to be out of reach.

Of course, none of this is what Stephen King likely meant to convey when he set out to pen a book of advice for the aspiring writer. But if there was anything to be gained from my strange, terrifying, weirdly exhilarating experiences of consuming many mediums at once, it was that – although the journey may take one far away from either included production’s initial purpose – the resulting skewage of predetermined reactions is a forbidden concoction that drives the mind into territories far inaccessible by a single-plane approach.

I read The Stranger. I listened to Hot Rats. It was one of the single most horrifying moments of my life. But – for as many such combinations exist – that particular class of eerie dread can never be conjured by any other pairing.

What other exclusive auras are out there?

2 replies on “Multidisciplinary Consumption”

To make it even stranger, the person singing about hot zits and roots and soots is not Zappa, but an even stranger personality by the name of Captain Beefheart. Try and check his music out …

Correction made – thank you for pointing this out!