In only two albums – one of which was recorded in front of a live audience – the MC5 attained a level of individuality merely hoped for by most acts of their era. They gained a rare victory over consumerism – but hardly anyone knows their name.

SAMUEL HYLAND

Last summer, my local train schedule left me two options: get to work an hour early, or arrive thirty minutes late. I chose the former. The product: for every day I had a job, I now had an hour of aimless wandering to kill in Central Park.

It wasn’t much of a predicament. I often used these walks to listen to new music, which I weighed upon a simple, yet cutthroat clause: If I got lost, the record was good; but, if I found myself walking my usual route, it was a waste of both a morning stroll and an album.

I have only gotten lost once.

The shame grander than even that? Most people aren’t familiar with who I was listening to:

The MC5.

All music doesn’t “sound the same,” as Madonna would suggest. Rather, it feels the same – and the basis of my criteria for a good “hour-early-walk-in-the-park” was founded mainly upon why I believe it shouldn’t. Modern-day consumerism has transferred the power of the music industry from the artist to the listener; so consequently, unlike what we saw when expressionism took over the art world in the 20th Century, today’s artists would rather appease the public than articulate themselves. This provides the floor of any such argument as that of myself and Madonna – both against the uniformity of sound – in that it uses what the consumer likes as the standard for what should be considered acceptable on a societal scale. Back to Ms. Ciccone’s point, each song, of course, does not sound exactly like the next. But, all music feels afraid. All music feels contrived. All music feels, in theory, the same.

And you don’t exactly get lost in Central Park listening to bullshit.

This is, for the most part, what intrigued me about the MC5. When you cross five shaggy-haired, tie-dye clad, guitar slinging gentlemen with the middle of America’s counterculture movement, the expectation is six or so rock albums that sound awfully close to what everyone else is doing. But this band wasn’t that. And that’s why I respected the hell out of them.

What I listened to on that eventful stroll through Central Park wasn’t a focused group of virtuosos, nor was it a convention of intellectuals who had mastered the mixolydian scale on keys, saxophone and mandolin – it was just a bunch of people who cared little enough to sound real.

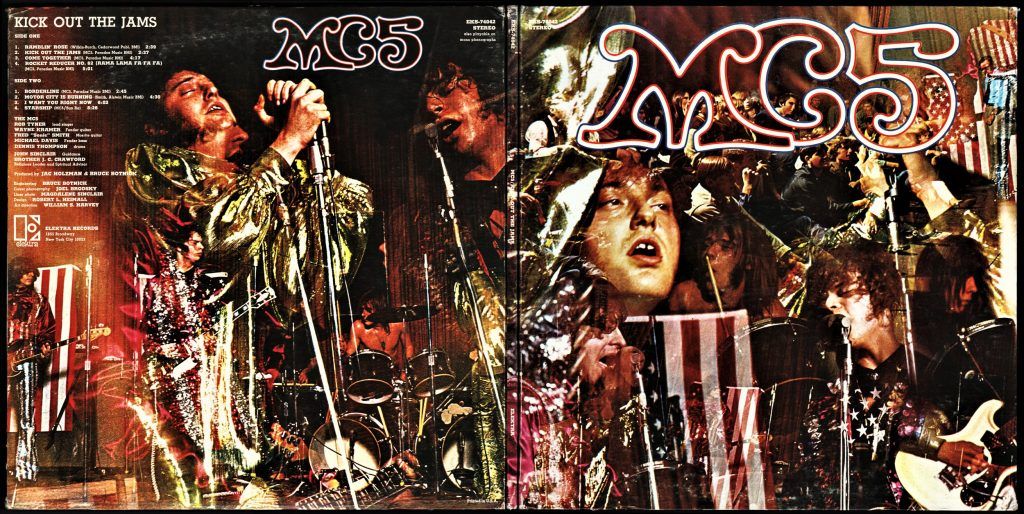

Exhibit A? Their first album was recorded live.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but even some of the greatest live acts we’ve seen – past and present – have not had the guts to record their debut records in front of a crowd.

Per Rolling Stone’s list of the top 50 live performers to grace a stage, only two of the top twenty acts recorded live albums within their first ten LP releases (Jay-Z and Rage Against the Machine, respectively) – let alone at all.

Yet, here were five shaggy-haired, tie-dye clad, guitar slinging gentlemen daring to ask the public through thirty-nine minutes of chaos: Are you gonna go to Woodstock, or are you gonna come over and jam in our basement?

And if you answered the former, you probably weren’t listening to the right record – because you would have been jamming in that damn basement within the first few songs.

That’s the attitude the band brought with Kick Out the Jams. They were loud. They were belligerent. And if you didn’t like it, they were going to make you.

Even the opening minute of the album can be said to epitomize this quality. It fades in, with sporadic shouts, audible commotion, and chanting that seems something out of Golding’s Lord of the Flies. Then, after about 40 seconds, Rob Tyner gets a hold of a microphone.

“I wanna hear some revolution out there y’all- … I wanna hear a little revolution,” he barks at the audience. He sounds more like a Soviet Baptist preacher than he does a lead vocalist. Then he takes us to church.

“Brothers and sisters,” he preaches, “the time has come for each and every one of you to decide whether you are gonna be the problem – or whether you are gonna be the solution.”

“That’s right,” one churchgoer/concertgoer (at this point, what’s the difference?) immediately cries out.

Tyner continues. “You must choose, brothers, you must choose. It takes five seconds. Five seconds to make a decision. Five seconds to realize your purpose here on the planet.” The conviction rises. “It takes five seconds to realize that it’s time to move – it’s time to get down with it. Brothers, it’s time to testify; I want to know: are you ready to testify?”

The entire room, it sounds like, erupts with praise. None seem to wonder what exactly they are testifying of – but that doesn’t matter, because whatever Pastor Tyner says is unquestionably true for as long as the microphone is in his hand.

Finally, he wraps up the sermon: “I’ll give you a testimonial,” he shouts, “…The MC5!”

And with that, the message is over – but the service is only beginning.

“The time has come for each and every one of you to decide whether you are going to be the problem – or whether you are going to be the solution.”

– Robin Tyner

Wayne Kramer’s Stratocaster screeches onto the scene, followed by the muddy rumbling of Michael Davis’ bass, all culminated by the combination of percussion and Kramer’s hoarse-ostrich-esque vocals about “Ramblin’ Rose”. The entire song is defined by a circular structure, similar to much of the blues music that became popular during its era. Unlike Bowie’s All Along the Watchtower, however, which was perhaps amongst the most popular songs boasting circular riffage at the time, there was no joker – no thief – no “way out of here”. You were here forever. And you were here to stay.

I specifically remember obeying the inclination to hop on a swing set, grinning to myself, that morning in Central Park throughout all that I just described. I smiled, because I didn’t know what was going on. I loved it.

What’s not to love, though: The MC5 are very likely only the tip of the iceberg, when it comes to underground groups at the birth of musical consumerism that were in it not to appease – but to express. There are hundreds of similarly-doctrined bands that we will never discover.

Rob Tyner himself spoke to this in a 1967 interview with John Sinclair. With the nudge of “Let’s talk about the music,” he lamented:

“Well, as I see it, the real music scene in Detroit is doing all right. But the whole – the population of all the musicians – and there’s an awful lot of young musicians in town – the percentage of these people who are really into it is so low that you never get to hear any of it.”

Given that they were the only representation of Detroit’s underground scene besides the Stooges (who would release their self-titled debut a year later), the MC5 had a lot on their backs post-Kick Out the Jams.

And, like I feel any artist should, they took it to the studio.

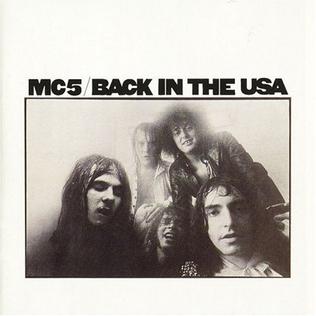

I listened to the group’s sophomore project Back In the USA (1970) not in Central Park, but in bed the following Saturday out of sheer intrigue for what I had heard a day prior – yet, despite my fears of this record sounding somewhat compromised due to its studio birthplace, I grinned ear to ear at the fact that even without the audience to egg them on — they remained five shaggy-haired, tie-dye clad, guitar slinging gentlemen who cared little enough to sound real.

The record label didn’t change them. The fans didn’t change them. The world didn’t change them.

Nothing would take them away from having church – whether the congregation was a mixing board, or hundreds of shouting hippies.

This, to me, is what music is supposed to be. The MC5 don’t get half the credit they deserve for their contribution(s) to music; and, for the most part, that’s why I was compelled by them in the first place – if there’s anything they can teach young listeners like myself a summer ago, it’s that if you’re thinking too hard, chances are it isn’t as creativity-based as it ought to be. I feel that when you perform to translate your soul into music, lyrics gain the power to become lifestyles – and who wouldn’t want the ability to do that?

Like Rob Tyner tells John Sinclair in the interview referenced above, “If you take a tune (…) and drag it out, it gets so much power, it’s like a mantra, you just say it until it’s got so much power that you can’t hold it anymore and it explodes, and it happens.”

Having listened to thirty-nine minutes of such power on a walk through Central Park is the proudest I’ve ever been to show up late for work.